Читать книгу Secret of the Satilfa - Ted Dunagan - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

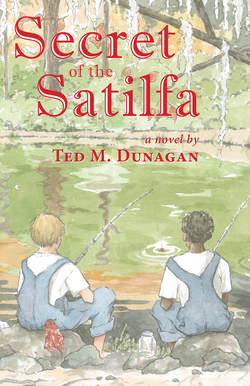

Chapter Three Going Fishing

ОглавлениеThe word got out about the spinning jenny and it wasn’t long before our cousins, our friends, and their cousins were all coming in droves.

We had discovered that if two riders got on, and a third person, preferably a strong and fast one, pushed the board around as hard as they could and jumped clean at the last second, then the spinning jenny would sling all but the most tenacious off the board, making it a contest to see who could stay on and who would be slung off.

It was used so much a round trench was worn in the ground underneath the ends of the board.

Soon there were crushed toes, skinned elbows and knees, heads conked when someone fell off instead of being slung off, and fights over who was going to ride it next.

Fred decided we were going to initiate a charge to ride, but before he could implement his toll, one of our cousins broke an arm.

Her parents, along with others, descended upon our momma with numerous complaints until one Saturday afternoon she marched out to the spinning jenny with my brother Ned and had him pull the plank off the stump and deposit it under the house.

And that was the end of the spinning jenny, which was all right with me. The thrill of it had diminished, and the only thing I regretted was that my friend Poudlum Robinson hadn’t had an opportunity to ride it.

I hadn’t seen Poudlum for a while. That was because he was black and we didn’t go to the same school. Since the warmth of summer had faded, I had only seen him a couple of times on weekends over at Miss Lena’s Store.

The store was halfway between his house and mine, so we met there sometimes and had us both a peach-flavored Nehi soda and an ice cream sandwich. We used the money we had secretly stashed away back during the summer. It was the reward we had given ourselves after discovering an illegal whiskey-making operation and the bootlegger’s cache of cash in a hollow tree way back in the woods on Satilfa Creek.

Thanksgiving weekend was coming up and Poudlum and I had planned weeks ago to spend it camping out at a fishing hole on that same creek.

My momma wasn’t too keen on the idea, but when I came home from school with the first prize for the Thanksgiving Poem, she relented and gave her permission.

My fifth-grade teacher had assigned everyone to write a poem about what they were thankful for. We had to turn them in on Tuesday, and on Wednesday afternoon before we were dismissed for the long weekend, she announced she was going to recite the winning poem.

I just about fell out of my seat when she began reading my Thanksgiving Poem:

I’m thankful for dressing and gravy

And the boys serving in the Navy

I’m thankful for turkey and ham

And for tough old Uncle Sam

I’m thankful for squash casserole

And for the heroes of old

I’m thankful for pecan pie

And for the beautiful sky

I’m thankful for bread and butter

And for my two brothers

I’m thankful for sweet potato pie

And for being old enough not to cry

I’m thankful for sweet ice tea

And for the opportunity to just be

I’m thankful for green beans and butter beans

And for all the children and the teens

I’m thankful for lemon glazed pound cake

And for being able to swim in the lake

I’m thankful for potato salad

And for the numbers when my friends are tallied

I’m thankful for being physically sustained

And for the grace of being spiritually without blame

The teacher gave me an A-plus and wrote a note to my momma on my poem informing her I had won first place. I could tell by the look on Momma’s face when she read it that I could go camping for a week if I wanted to.

Poudlum and I planned to meet at Miss Lena’s Store on Friday after Thanksgiving Day, right after our noon meal. That way we would have time to walk to the Cypress Hole on the Satilfa, set up camp, and get in some fishing before it got dark. I just hoped he had done something to make his momma happy, too.

Thanksgiving Day came and went. Since my daddy was gone we all went to Aunt Cleo’s and Uncle Elmer’s house and ate turkey and all the trimmings with them.

On Friday, I was anxious to get going. My momma served up big bowls of steaming vegetable soup with corn bread and buttermilk, which was a welcome change from all the rich food the day before.

While I was sopping up the dregs of the soup with a piece of cornbread, she was fixing me a bag of biscuits left over from breakfast. She would bore a hole into them with her finger and pour the hole full of Blue Ribbon cane syrup, pinch the hole closed, and then wrap them up in waxed paper.

“These biscuits will fill you up in case you and Poudlum don’t catch any fish,” she said. “But I ’spect y’all will, cause black folks know how to fish. I want y’all to be real careful around that water now,” she concluded as she began packing my stuff into a small cotton picking sack.

She had allowed me to take one of her old skillets, a small one, along with an old quilt, a box of matches, a packet of salt, some cornmeal, and a half-pint jar filled with lard to fry the fish in.

“You got your pocketknife?” she asked.

“Yes, ma’am, and Ned sharpened it real good for me this morning so I can scale them fish and clean them properly,” I said as I slipped the strap of the sack over my shoulder.

My momma hugged me and said, “Now remember, if y’all get too cold or hungry just go to your Uncle Curtis’s house. It’s not too far from the creek.”

The strap of the sack was cutting into my shoulder before I got to the store. I hoped Poudlum’s load was lighter so we could take turns carrying mine. The only thing I had told him to bring was a quilt and some fish hooks.

He was nowhere in sight when I arrived at the store, so I set my sack by the steps at the front door, went in, and started gathering some supplies just in case the fish weren’t biting. I didn’t want to be stuck in the woods hungry with nothing except biscuits to eat.

We planned to be there two nights, so I counted the meals in my mind while I selected cans of Vienna sausage, sardines, potted meat, pork and beans, and four dime boxes of saltines. We didn’t have to worry about anything to drink; we could just drink water from the creek.

“Good Lord,” Lena cried out when I piled it all on the counter. “Son, what you planning to with all this stuff?”

“Me and Poudlum gonna camp out and fish on the creek. This stuff is just in case we don’t catch any fish.”

After she bagged it all up I paid her and went outside and stuffed it all into my sack even as I became concerned about the weight of it.

I looked down Center Point Road, shading my eyes from the sun with my hand, and saw no sign of Poudlum. I hated the thought that I might have to walk all the way over to his house and try to convince Mrs. Robinson to let him go, but I knew Lena would watch my stuff if I did.

After waiting about half an hour I went back into the store and got myself a Nehi and sat on the front steps nursing it while I gazed down the dirt road looking for my friend.

I began to wonder what I would do if he didn’t come. Just go on by myself or go back home and share all the stuff in my sack with my brothers?

I didn’t think I wanted to sleep on the bank of the Satilfa by myself, but still, I didn’t want to give up.

Miss Lena came outside and stayed on the steps with me. “You think maybe Poudlum isn’t coming?” she asked softly.

“I don’t know, but it’s not like him not to at least come tell me if he’s not.”

After another thirty minutes I got angry and defiant. I stood up, shouldered my sack and started walking down Center Point Road toward the creek. Over my shoulder, I called back to Miss Lena, “I’m going fishing, and I’ll be at the Cypress Hole if anybody’s looking for me.”

I had to stop and rest twice before I got to the Church. Even though I kept switching my sack from shoulder to shoulder, the strap bit painfully into it as I walked, and it grew heavier and heavier with each step I took.

The sun was still beaming warmth down when I crossed the Mill Creek Bridge. Halfway up the hill beyond it I could see the sun striking gold from the mica stones in the ditch.

That was about the time I heard the ruckus coming from back behind me. Somebody was yelling. I cocked my head, listened real hard and heard a faint voice yelling, “Mister Ted, wait up, I’m a comin’!”

I recognized my friend’s voice and was elated that he was coming after all. The day took on a whole new outlook as my excitement about the venture returned. I stepped off the road, set my sack down in the shade of a big black gum tree, and waited.

It wasn’t long before Poudlum came trotting up with a wet sheen on his face. He stopped in the middle of the road when he saw me and said, “Hey, Mister Ted.”

“I done told you I ain’t no mister. I’m just Ted.”

“I keeps forgettin’. But anyway, I’m here, even if I is late.”

“What happened to you? I waited forever on you.”

“We got company. Dey been here all week, and my momma thought I ought not to run off and leave my cousins. But I finally got her away from all dem folks and told her dat I had promised Mister Ted we was going fishing. She thinks a lot of you, so when I mentions yo’ name she packed up a syrup bucket full of biscuits and side meat and told me to git. When I got to de store Miss Lena told me you had already started down de road. I been walking real fast and running some to catch up wid you.”

I was so happy to see Poudlum that I didn’t care about the details of his tardiness; I was just pleased that he was finally with me.

“What you got in your sack besides a syrup bucket full of biscuits?”

“I got some fishing line, some hooks, and some corks.”

“That don’t sound heavy at all. Mine’s about to cut through my shoulder. Would you carry it a while for me and I’ll carry yours?”

“Shore I will,” Poudlum said as he shouldered my sack. “Lawd, what you gots in it, rocks?”

We stopped to rest again a ways on down the road, secured our bags in some tall weeds, climbed down a steep bank, and drank our fill from a spring we knew about. The water was cool, crystal clear, and sweet to the taste as it came bubbling up out of the ground. It was only about two inches deep, and as I lay on my belly I could see sunlight reflecting gold glints off the sand beneath the water.

We rested for a while before we got back on the road, anxious to begin our adventure on the creek. But we hadn’t gone far before Poudlum began asking questions.

“Dis fishing hole we heading for, de Cypress Hole, colored folks ain’t usually allowed to fish at it. Why you think dat is?”

That was a perplexing question and I wasn’t sure how to answer it, but after a little thought I told Poudlum, “I think it’s ’cause they ’fraid y’all would catch all the fish in it.” I knew it wasn’t the real answer, but I didn’t know how to say the real reason without hurting his feelings. I think he knew the real reason, but I could tell he appreciated my answer as the way I felt, because he grinned and said, “Why you ’spect it’s called de Cypress Hole?”

“Probably ’cause there’s a lot of cypress trees around it.”

“De water deep in it?”

“There’s a big deep place right below the shoals, which is the Cypress Hole. That’s where we’ll fish.”

“What’s a shoal?”

“Uh, that’s a place in a stream where the water is running over a lot of rocks. We can walk across the creek on those rocks. That’s what we’ll do when we set out our trot line.”

“What kinda fish you think we gonna catch?”

“Catfish and perch, that’s all there is in there.”

“What we gon use for bait?”

“We’ll catch some crickets and grasshoppers when we get there. Plus there’s some dead pine trees we can get grub worms out of. I brought a little empty pint jar we can put them in.”

“What if you fished without no bait?”

“You mean just throw an empty fish hook in the water?

“Uh-huh.”

“Wouldn’t nothing happen, Poudlum. Why, that would be kind of like licking a clean plate.”

There was a little swampy area about a quarter of a mile before we got to the Satilfa where a big stand of bamboo grew. We stopped there and cut us some fishing poles. We cut four in case we happened to break one, plus we planned to use some of the joints in the bamboo to make whistles out of later while we sat around the fire.

I used the small blade of my pocketknife to cut the poles down because I wanted to keep the big blade sharp to clean the fish with.

Once we had cut the tops off and stripped the poles clean, Poudlum carried them and his sack while I took my turn carrying my heavier sack.

A little further up the road I knew the Satilfa Creek Bridge would come into sight just around the next curve.

When we rounded that curve we both stopped and stared for a moment because there was a vehicle in the road up ahead.

I squinted my eyes and recognized my Uncle Curvin’s old pickup truck. It had a jack under the front of it with the truck lifted up off the ground. My uncle had had a flat tire.

At that moment he appeared from around the back of the truck rolling his spare tire. He wasn’t having an easy time because my uncle was crippled from a war wound.

“Dat looks like yo’ Uncle Curvin up ahead,” Poudlum said.

“Yeah, that’s him. Looks like he got a flat.”

“He look like he so skinny it would take two of him just to make a shadow.”

“Yeah, he’s skinny all right,” I said. “He’s also crippled. Let’s go give him a hand.”

My uncle was mighty proud to see us. We loosened the lug nuts on his flat tire, replaced it with his spare and jacked his truck down for him.

“Thank you, boys,” he said. “Y’all heading for the Cypress Hole to do some fishing?”

“Yes, sir,” I told him. “We gonna camp out and fish for a couple of nights. Where you coming from?”

“I been up to Grove Hill, and, Lord have mercy, boys, a terrible thing happened there this morning, with me right slap dab in the middle of it!”