Читать книгу Secret of the Satilfa - Ted Dunagan - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

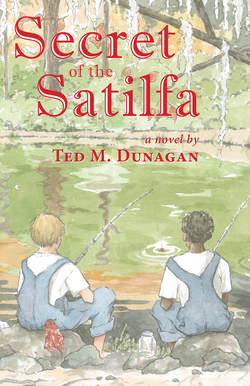

Chapter Four The Cypress Hole

ОглавлениеPoudlum and I both thought a lot of my Uncle Curvin. We had picked cotton for him back during the summer and he had always been mighty good to us. We also admired him because he had fought in World War One all the way over in Europe and got himself shot in the leg, which crippled him but did entitle him to a small disability check that came in the mail each month from the government.

He looked the same as always, wearing his old brown slouch hat with sweat stains on it, a blue, long-sleeved work shirt, and a pair of overalls. Beneath his hat, his face was all caved in because he didn’t have any teeth.

“What in the world happened up there, Uncle Curvin?” I asked.

“I went up there to cash my check at the bank and all heck broke loose while Mrs. Vinny was counting out my money. She was telling me how she wanted to buy a bushel of sweet taters when all of a sudden she stopped talking and her eyes got big as saucers. I could tell she was looking at something behind me, so I turned around. You boys won’t never believe what I was looking at!”

“We might, if you would just tell us. What was it?” I asked.

“Scared me worsen I been scared since I was in the war. Came might near wetting my pants on myself. I been shaking like a leaf in a windstorm ever since.”

“Shore sound like it wuz something real bad,” Poudlum said.

“Yeah, maybe we’ll find out what it was one of these days,” I said with a sideways glance toward Poudlum, but my words were directed toward my uncle to let him know we were getting a bit impatient.

Uncle Curvin sank down on the running board of his truck like he was worn down to a frazzle. Whatever had happened to him, it had just about got the best of him.

“Y’all just keep your britches on and I’ll tell what it was I saw when I turned around.”

We stepped closer and squatted down in front of him in anticipation.

“When I turned around, boys, I was looking down both barrels of a sawed-off double-barreled twelve-gauge shotgun. And it was scary, ’cause I knew that thing could scatter me to kingdom come.”

“Good Lord, Uncle Curvin!” I exclaimed. “Was it a bank robber?”

“They was two of them,” he said. “The other one had a mean-looking pistol that he was waving around.”

“What did you do, Mister Curvin?” Poudlum asked, wide-eyed as an owl at dusk dark.

“Why, I did exactly what he told me to. I got face down on the floor and started praying.”

“They told you to pray?” I asked.

“Naw, I done that on my own.”

“Then what happened?”

“Well, the one with the scattergun held everybody at bay while the other one went behind the counter and cleaned out all the money. I peeked up and saw that my little pile of money was still laying on the counter.

“The one with the pistol grabbed it when he came out from behind the counter with his sack of money, but the other one jerked it out of his hand and dropped it down on the floor next to me on their way out of the bank.”

“So you didn’t lose your money?”

“Nary a dime of it. Got it all right here in the bib pocket of my overalls. I don’t know why they done that, but I shore do appreciate them not taking my pitiful little pension. A lot of rich folks can afford to lose a lot of money more than I can afford to lose these few dollars.”

“Did they catch ’em, Mister Curvin?”

“Naw, they got clean away. Wouldn’t nobody to stop ’em.”

“How about the law?” I asked.

“Shoot, the law was all out collecting their cut from the bootleggers. Mr. Leon Stringer, he owns the bank you know, went running outside after the robbers left with his necktie and suit coat flapping in the wind and went straight over to the sheriff’s office, but couldn’t find nobody there except the jailer. That’s what he told us when he come back. That sorry excuse for a sheriff, Elroy Crowe, showed up ’bout a half hour later, just long enough for the trail to get cold.”

“Sounds like dem bank robbers got clean away,” Poudlum said.

“Well, somebody did see ’em leave town heading down Highway 84 toward Coffeeville. Sheriff Crowe got on his radio and had somebody put up a road block down there to stop them from taking the ferry across the Tombigbee River, ’cause he said they were probably trying to get across the Mississippi State Line.”

“Did they get across the river?” I asked.

“Naw. I heard everything on the sheriff’s radio. They skidded around when they come up on the road block and headed back up Highway 84. They found their abandoned vehicle ’side the bridge over the Satilfa Creek, and figured they were heading down the creek toward the river on foot. Last I heard they were talking about getting some dogs together and start tracking them.”

“Whew, you done had yourself a day, Uncle Curvin. You saw a bank robbery, and then on top of that, had yourself a flat tire.”

He got up off the running board and started getting in his truck when he said, “You got that right, son. I believe I’m going home and lay down for a spell. I ain’t used to bank robbers and flat tires.”

He cranked up his truck, put it in gear, leaned out the window and said, “How long you boys plan to fish?”

“Tonight and tomorrow night, and then we’ll probably go home Sunday morning,” I told him.

“I might mosey over here and check on y’all sometime this weekend.”

“We’ll be at the Cypress Hole, and we got two extra poles. Come on by.”

“I expect I might. Good luck, boys,” he called out through the truck window as he pulled out onto the road. We watched until his dust trail disappeared around the curve.

Poudlum scratched his head and said, “You don’t think he made all dat stuff up, do you?”

“Naw, he wouldn’t do that. Come on, the trail to the Cypress Hole is right up yonder on the left.”

“Well, I just hopes dem bank robbers did head down de creek towards de river and not back up de creek dis way.”

“They probably want to get to Mississippi, like the sheriff said. They wouldn’t come back up this way,” I reassured him.

We could see the bridge over the creek when we turned off the road onto the trail that angled through the woods to our destination. On both sides of the trail there were great red oaks and cedar trees, thick with tangled muscadine vines. The wild grapes had long ago been consumed by squirrels and raccoons. I liked those wild grapes. You could pop one in your mouth, bite down on it and it would burst in your mouth and render a sweet, tangy juice. There were seeds which you had to spit out, and the hull, after you chewed on it a little. My momma made some delicious jelly from the juice of them. She even made preserves from the hulls. They were both tasty inside a biscuit.

The trail was like a tunnel with tree branches forming a canopy above your head. A little further into the woods and the cypress trees began to appear with long draping ribbons of Spanish moss hanging from the limbs.

“Dis is spooky,” Poudlum uttered in almost a whisper.

“Don’t worry,” I said. “It opens up into a big clearing just a little ways up on the creek bank.”

We emerged from the trail and there it was, the place where Ned and Fred and I swam in the summer and the best fishing hole on the creek. You could see the sky up through a large opening of the forest.

Poudlum turned in a complete circle, taking it all in. “Now, I likes dis place,” he said. “It’s big and open. And look over there, it looks like somebody had a fire built over by de creek bank.”

What he was referring to was a circle of big round creek rocks, blackened with soot, where the previous campers had built their fire.

The sound of the water was the best part. It swept gurgling and churning over the flat rocks of the shoals before dropping into the pool below. That pool was where the fish were.

Poudlum noticed, too. “Dat water spilling over dem rocks shore do sound fine. It soothes you kind of like when my momma sings a hymn at night.”

“Yeah, I like the way it sounds too. We’ll sleep real fine tonight listening to it. But first we have some work to do. Let’s set our sacks down and start gathering firewood. We’ll need a big stack of it so we can keep the fire going all night. It’ll get cold soon as the sun goes down.”

We stashed our stuff next to the fire bed and began dragging and carrying limbs and sticks out of the surrounding woods. Soon we had enough to last us through the night and into the cold morning.

We even found a long-dead loblolly pine, which had rotted away except for the heart that had turned into lighter wood. We broke it into pieces knowing all we had to do was stick a lit match to it and it would blaze up because of the turpentine in it.

There was also an abundant supply of lighter knots, the remnants of where the branches had been attached to the trunk. They looked like an elbow and were handy to throw on a bed of coals that had died down, to get a quick blaze going again.

The next item on our agenda was to gather some fish bait. Poudlum had that covered. “I passed a big dead pine tree over yonder that’s about half rotten and I could hear dem sawyers inside it.”

Sawyers were fat, round, white grub worms with two little red pincers on their head, which they used to eat dead pine trees. And Poudlum was correct, you could hear them inside of a dead tree if you listened real close. They made a kind of steady smacking sound. I supposed it was them eating wood that made the sound. I never knew why they were called what they were, but figured it was because they were actually sawing the dead log up with those little pincers on their head. What I did know was that catfish loved them, and so did perch.

When we got to the tree we pulled the loose bark off the trunk in hunks and dug the fat grubs out of the rotten wood until we had our jar almost full.

“How many you think we got, Poudlum?”

“I ’spect about fifty. You think dat’s enough?”

“Yeah, that’s plenty for tonight. Crumble up a handful of rotten wood and put in the jar so they’ll have something to eat.”

After Poudlum screwed the cap on the jar I took the small blade of my knife and jabbed a few air holes into it.

It was still warm, but I knew the air would take on a chill as soon as the sun went behind the trees. It was time to set up our trot line. Poudlum held the ball of cord on the bank, and after I had slipped off my shoes and socks, I rolled up my pants legs and waded through the swift running water toward the other side of the creek with my end of the cord. Then I pulled out a little extra slack so I would have enough cord to tie it to a tree. Now that I had measured the length of cord we would need, I returned to where Poudlum was holding the other end.

“What do we do next?” Poudlum asked.

“Unravel about six more feet so it’ll have enough slack to go past the shoal and drop into the pool below it.”

We stretched our measured cord out across the clearing on the ground. Then we cut a bunch of two-foot pieces of cord and got down on our knees and tied the short cords every few feet along the length of our trot line. Then we went back and attached a fish hook and a small lead sinker on the end of each short piece of cord. It was tedious work, but it was a good way to catch a lot of fish.

We stood back and admired our work. “Nothing left to do except bait the hooks,” I told Poudlum. “Then we’ll stretch it out across the creek, tie both ends to trees and drop it over into the deep water.”

The fat worms wiggled and attempted to bite us with their tiny pincers when we stuck them with the fish hooks.

“You ’spect dat hurts ’em when we sticks ’em?” Poudlum asked.

“Naw, they just worms.”

“Den how come dey twists around and wiggles so?”

“I don’t know. Probably it’s just a reflex or something like that. Come on, let’s get ’em in the water while they’re still wiggling so they’ll attract the fish.”

We tied one end of the trot line to a stump near the creek bank on our side, and once again, I crossed over, but this time I secured the end to a tree and watched as the water washed the line over into the deep pool.

“How you tells when a fish gets on it?”

“You can’t,” I said while I was getting my shoes and socks back on. “We’ll just have to run it ever so often. We’ll do it just before dark so if any fish are on it we’ll have time to clean them. After that we’ll put more bait on if we need to and run it again in the morning.”

We rigged up our cane poles with hooks, lines, and sinkers, baited the hooks and settled down on the side of the creek to fish in the fading light of the day.

The gurgle of the water coupled with the surrounding solitude created the exact atmosphere we had been yearning for, and we knew then that all our planning, cajoling, walking, and work had been worth it.

The trees had lost most of their leaves and the fading light filtered through the branches and played light games on the water’s surface as our corks bobbed listlessly on the ever-changing silver liquid of the dark pool we gazed into.

Something was not as it should be.

I shook off the hypnotic feeling and realized that Poudlum’s cork was what was missing. It had disappeared beneath the surface and the only thing visible was the straight line going into the water.

“Poudlum!” I cried out. “You got one! Hold on tight to your pole!”

“Good Lawd!” Poudlum exclaimed as he stood up and got a good grip on his pole. “It feels like a big one, too!”

We threw several back, but when we quit just before dark we had four fat catfish and three perch as wide as your hand. I began cleaning them and had them ready to fry by the time Poudlum got a fire going.

“It’s just about dark,” Poudlum said. “Don’t you think it’s about time we run dat trot line?”

While I was removing my shoes in preparation to check the trot line, I glanced across the creek, lowered my head, then jerked it back up.

Had something moved over there? I strained my eyes, but the light was beginning to fade.

A peculiar feeling swept over me. I put my feet back in my shoes and told Poudlum we would wait until the morning to check the trot line.

I also asked him to put some more wood on the fire.