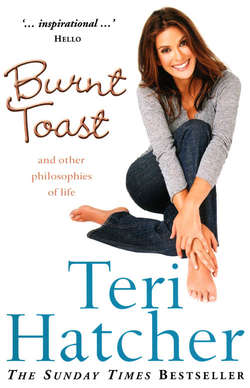

Читать книгу Burnt Toast - Teri Hatcher - Страница 8

Place on Rack and Let Cool

ОглавлениеRock bottom. You never know how far down you are until you hit it. Near the end of my marriage, that’s where I found myself. Eating burnt toast is one thing – you’re unnecessarily suffering a discomfort of your own making – but being toast is a whole different story. When you’re toast, you yourself are that burnt, useless piece of bread. You’re a goner, doomed and destroyed. Ever tried to un-toast a piece of bread? When you’re toast, there’s no going back. The garbage can is your best and only option.

That’s how it felt to me after nearly four years in New York. At my lowest of lows I called my friend Val from Chelsea Piers in New York City. It was almost Christmas, and New York was cold. The snow on the ground had long cycled past the pretty phase and was well into the gray and dirty phase. Old, foul, brown slush had melted into deep muddy puddles at every curb. If you’ve never experienced these “puddles,” what you have to know is that they’re optical illusions. Because of the snow floating on top, they look relatively solid. But when you step into them you’re suddenly in a calf-deep, boot-defying puddle. Every street corner is a cruel joke. At the same time, the invisible bottom had fallen out of my marriage. I was at my wit’s end. I needed to get out, but I couldn’t stand to fail. I know, this from the girl who kept a scrapbook page of her failures in high school. Couldn’t I just add my marriage to the list and be done with it? But I had no tools for recovering from failure. The scrapbook that held my rejection from the San Francisco Ballet, and later letters of denial from UC Berkeley and UCLA, was some sort of self-punishment tied to perfectionism. I didn’t want to disappoint my parents, my father specifically, and if I were perfect I wouldn’t have to put any more letters on my failure page.

But that day on the edge of the pier, I knew I was facing a problem I couldn’t solve. I couldn’t stay in the marriage any longer. Yet I wasn’t ready to accept failure either. I couldn’t accept what divorce might do to my daughter – that I might cause her pain. There was no good option. I stood on the edge of that windy pier crying into the phone. I said to Val, “I don’t know what’s preventing me from just throwing myself in the Hudson.” Val said, “Teri, first I want you to step away from the river.” And of course I did. I couldn’t imagine doing that to my daughter. But for a moment I’d looked down at the biggest icy puddle ever and had seen it as a haven. I knew the time had arrived. I knew the marriage was over. How had I gotten here?

Turning forty wasn’t the first time it ever occurred to me that I wanted to change something about my life. But ten years earlier, when I was thirty, I thought that changes happened on the outside. They were big, concrete, physical. In order to change my attitude about jumping off a cliff I thought I had to…jump off a cliff. Moving across the country was meant to be a fresh start. I’d be a full-time mother. My husband, Jon, would be near the theater culture that was important to him, and I thought it would be good for all of us.

Jon, Emerson, and I took the long route to our new home – we drove across the country. We had twenty-one days, three guidebooks, and an apartment that would be clean and ready by the time we got to Manhattan. It was kind of a freewheeling trip, as every cross-country trip should be. Along with “free-wheeling,” I’m pretty good at “wingin’ it,” so I thought I was in my element when we got to Missoula, Montana, and noticed that there were quite a few motorcyclists around. (And when I say “quite a few” I mean thousands.) Apparently, we were just in time for the annual Sturgis Motorcycle Rally, when about a half million bikers make their way to Sturgis, South Dakota, to converge at the mother of all motorcycle gatherings. At first we thought it was kind of cool, all those beleathered bikers escorting us down the highway. You just had to keep a careful eye on your blind spot. But then, as it got later and we started looking for a hotel, we saw the effect that the convergence of a half million bikers has on western civilization. Every hotel, bed and breakfast, and campsite from Montana to Wyoming was booked. Who knew bikers were so organized? As a last resort, we went to a 7-Eleven, planning to park there and sleep in the car. We went up to the register to ask if it was okay to stay the night in the parking lot and to offer the cashier twenty bucks for all-night access to the bathroom. But the guy took one look at Emerson, who was sleeping in my arms, and said, “You can’t be sleeping in the car. Come around the corner and sleep at our place.” It was one of those sweet, kindness-of-stranger gestures (he definitely didn’t recognize me). And that’s how I found myself lying wide awake on the floor of a stranger’s apartment in the middle of Montana clutching my infant daughter in fear as my husband huddled beside me and the sound of a violent horror movie floated in from the TV in the next room. I nearly smothered Emerson, afraid that if I loosened my grip someone would steal her, and of course I didn’t sleep a wink. At six in the morning we bolted, leaving a thank-you note and fifty bucks.

We hit Mount Rushmore, where it was hailing. In the middle of August. As the hail beat down on our car, the rhythm of the ice sounded like “Love Me Tender.” Suddenly I had to go to Graceland. Needless to say, it wasn’t the most direct route to New York. In fact, it was exactly one thousand miles out of the way. But who hasn’t wanted to throw up their arms in the middle of a hailstorm and shout, “We’re going to Graceland!”?

The three books I brought on the trip were an atlas, Fodor’s USA, and Eat Your Way Across the U.S.A. by Jane and Michael Stern. The last one is a guide to the most unforgettable, inexpensive, best eats across America – from pie palaces to small-town cafés. We headed to Nebraska for the best fried chicken in the country. It was a ma-and-pa place, and we got there at seven, just as they were closing. (Because that’s when ma-and-pa restaurants close? Seven?) I pleaded with the “ma,” of the “ma and pa,” telling her, “You don’t understand. We drove all the way from Los Angeles to taste your fried chicken!” She relented, and the fried chicken was really good, except it came with ambrosia salad, which I could do without. Then we went to St. Louis just for ribs.

I liked this new feeling, like I could disappear into the middle of the country. After being in the spotlight of the tabloids, and focusing on acting and appearance and glamour, that was all I wanted. Every day brought something new, and I felt myself emerging from Hollywood and coming back to being an American. I loved the vastness of America. It was so big and we were so insignificant. But that feeling started to wear out as the days went on. At the beginning of every day, Jon and I would tell ourselves, “This is gonna be a great day.” But by noon we’d be fighting, and by evening we’d be exhausted. I spent at least fifty percent of the time in the backseat with my boob manipulated so Emerson could nurse while strapped into her car seat. The things we do to drive another hundred miles.