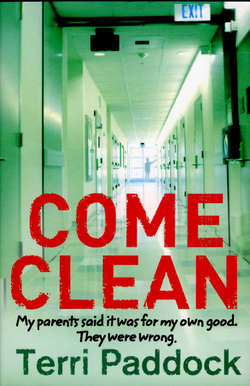

Читать книгу Come Clean - Terri Paddock - Страница 12

CHAPTER SEVEN

ОглавлениеWhen I come to, I’m in a room smaller than the intake room and it’s dark. There are no windows and the only light is eking through beneath the door that I don’t even need to touch to know is locked. My tartan skirt has hiked up to expose my legs and the soft skin at the backs of my thighs is sticking to the cracked leatherette cushions of the couch I’ve been laid out on. I can’t breathe. I wonder for a second if my lungs stopped working when I fainted because I’m puffing now like I’ve been under water: like when you used to dunk me at the swimming pool and I’d get chlorine up my nose and I couldn’t breathe, and you’d hold my head under while you chanted Marco Polo Marco Polo, and I couldn’t wait to do the same to you once it was my turn. My other vital organs feel as if they stopped and started again too. I’m hot and cold at the same time and my heart is thwacking inside my chest.

I don’t know how long I’ve been in here, hours probably. I try to read my Swatch, my favourite Christmas present last year. I love it, I’ve always loved everything you gave me. Even though it’s near impossible to tell the time because there isn’t a second hand and no numbers. You’d tease me by saying I was the ditzy one – spatially retarded in fact – not the watch. Retard, you’d call me, but you’d say it with affection and that’s how I’d hear it too. In the dimness, the hands are too fuzzy to discern at all. The room has an undisturbed air about it, like no one but me, twisting in my unconsciousness, has moved in here for quite some time.

My memory is one thing that didn’t stop working when I passed out. I know exactly where I am, if not the precise location within the building.

And I know I’ve got to escape. I try to retrace the route in my head so I can tell Cindy. But what the heck is the name of the road, Justine? Is it right or left off the main drag? And how many miles after Harvey’s? I don’t know. Cindy will figure it out. She has to. She and Lloyd will find a map and find a way, they’ll get me out of here.

I’ve just got to reach a phone so I can call her. I survey the room, my eyes adjusting to the dark. I can make out forms though colours and textures blur into shadow. There’s the couch I’m lying on, about a foot shorter than me, and two folding chairs, leaning up against the wall to the right of the door, and a trash can, wicker maybe, looking empty and skeletal even in the dimness, and framed things on the wall, yet more needlepoint godsquad pronouncements I’m sure. To the left of the sofa where my feet have been dangling is a spindly side table and there’s something on it. It’s not a phone, though, that’s clear. It’s smaller, looks like a tube or canister of something. I lean in and squint. No, it’s a cup, a plastic cup, but it’s tipped over on its side, thanks apparently to a collision with my feet. The tabletop is a pool of liquid, dripping into the carpet. I dab my finger in it. Water, my glass of water.

I remember how thirsty I am. My lips crack with rawness and when I lick them my tongue sticks like it does to my teeth and the underside of my still foul-tasting retainer. I would hock my Michael Jackson collection and all my Esprit sweaters for a drink of water.

Why would anybody put a glass of water in a place like that, where a person could so easily reach out and kick it accidentally. It’s almost laughable, the sheer stupidity of it. But then it occurs to me. It wasn’t a stupid thing, not thoughtless at all. Plenty of thought went into it. They did it on purpose. She did it, Hilary.

She did it to spite me. She did it so that when our mom lost the steel in her lip, started feeling guilty later and called up to see how I was adjusting and asked, is my Justine OK, did you give my baby her glass of water? Then Hilary would be able to say with a straight face and clear conscience, ‘Of course we did, Mrs Ziegler.’ And Mom wouldn’t think to ask, ‘But did she drink the damn water, or did you, you evil woman, put it somewhere it was certain to get knocked over so she’d never get a drop of it?’ Mom wouldn’t think to ask that and she’d go to sleep tonight never realising how thirsty I am or how dry my lips are or how I’ve got nothing to wash down this taste of bile and vomit and betrayal.

There’s movement on the other side of the door. Rigid with fear, I listen to the chatter of the key ring on the other side, the scraping of metal on metal as the key’s teeth match up with the lock’s grooves, then the turning of the mechanisms deep inside and then the click-thud as the bolt snaps back. Should I hide? There’s nowhere. Should I pretend to be asleep? Wait behind the door to pounce? Throw the wicker wastepaper basket over her head? Even as I’m asking myself, I’m imagining Hilary twirling the massive ring of keys round her neck like a witch doctor spins a string of skulls, working his spell over each of his victims.

But when the door opens, there’s no Hilary. Instead there’s a girl. She flips on the lights too suddenly and almost blinds me, but I can see her through my squinted lids. I don’t know her. She’s dressed in a billowy red sweat suit and is several inches shorter than me and wider, almost round like a ball, with pale skin and straight red hair, greasy and slicked back into a ponytail twitching high and off-centre atop her head.

Mark and Leroy are back, lingering behind Pony Girl in the hall and they don’t enter all the way when she does. She sashays in swinging a Kmart plastic bag which she flings on to the sofa. ‘Your clothes,’ she says.

‘I’m fine in what I’m wearing, thanks.’

‘Not regulation.’ She tosses her hair and gestures towards the bag again.

I reach into it. There’s a green synthetic tunic littered with pink polka dots and a pair of brown corduroy pants. I hate cords at the best of times, the sound they make as you walk, the friction, the ribbons of material rubbing up against one another, leaving funny brush patterns and picking up lint from wherever you sit down. I hate them and these ones are two sizes too big, cheap and nasty to boot. Very cheap, judging by the price tags still attached to them as well as the tunic.

‘These aren’t my clothes,’ I tell Pony Girl.

‘Your parents brought them for you.’

Our parents?

I take a step towards her. ‘Did they come back? Are they still here?’

‘No, they left them here,’ she says, her breath stinking in my face. What’s that smell? ‘They left them when they left you.’

I rub the bridge of my nose. There’s a spot there where, if I close my eyes and press hard enough, it feels like I’m giving my brain a pinch. A little squeeze that rockets pain like prismed light into my thoughts. It hurts most when I use the knuckle of my forefinger, but it only hurts for a second and then sometimes it helps. It makes things clearer.

Like now, like how it’s clear to me now that our parents must have had this planned, who knew how far in advance. Maybe weeks, maybe hours. Time enough for Mom to go shopping at Kmart. Perhaps she went this morning while I was still asleep, dreaming of you and swimming – how long ago was that?

I can’t fathom it, nor can I fathom how my very own mother could shop for me at Kmart of all places. We never shop at Kmart. And how could she pick out quite such an atrocious outfit? I’ll look like a tree with the brown pants and the green top – a cherry tree, even, thanks to those hideous pink polka dots. What was she thinking?

But hang on a minute. Perhaps it isn’t all bad. There is only one change of clothes. You don’t give a person just one change of clothes if you expect them to be gone a long while. It is only an evaluation, isn’t it? After three days I’ll be able to go home again and everything will be peachy keen. Maybe I’ll only have to stay one day. One change of clothes, one day.

‘You can change into them after the strip-search,’ the redhead says.

‘The what?’

‘Strip-search. We’ve got to check you ain’t trying to sneak any contraband into the programme.’

‘You must be kidding.’

“Fraid not.’

‘I don’t have any contraband and I’m no way going to take my clothes off to prove it.’

‘Sorry, chickie,’ she says, not appearing the least bit apologetic. ‘Them’s the breaks.’

‘No way. Uh-uh.’

She reaches out and picks at the hem of your turtleneck. A loose thread dangles and she yanks at it until it breaks, causing the material to bunch up round the stitching at the edge. ‘I’m not gonna have to get Mark and Leroy there to restrain you, am I? You wouldn’t like it that way, I bet you wouldn’t.’

On cue, the two bruisers square their shoulders and bristle threateningly. Around the corners of Leroy’s mouth flickers a faint hint of a smile.

My own shoulders slump and I can feel my lower lip start to quiver. I blink and focus on a point on the wall. I can read the needlepoint now: ‘The Lord is My Shepherd’ it tells me. ‘No,’ I say.

‘Good, it’s always so much easier with a little cooperation.’ From the back pocket of her sweat pants, Pony Girl unfurls a pair of rubber gloves. Not the surgical kind, skintight and unobtrusive. These are kitchen gloves. Thick and bright yellow, the kind you use when you pick up Brillo pads and scrape the grill after a barbecue or when you want to clean the oven.

Mom used to wear gloves like that, I recall, when we were little. She warned us not to listen to that flimflam about dishwashing liquids that were good for you – no matter what the commercials said, the grease, the suds, the serrated edges of steak knives and the tines of all those grimy forks, those things were bad bad bad for your skin. You had to wear gloves to protect your hands, to keep them young and unlined and so as not to break your nails, especially after you just paid five dollars for a manicure. Mom would kick up a fuss if she couldn’t find her kitchen gloves, which she couldn’t sometimes if we’d swiped them from their place, under the sink with the Drano and the vacuum bags. We liked to play dress-up with them. You’d pretend they were evening gloves, the elbow-length satiny kind like Audrey Hepburn would wear in those old films you liked to watch.

Mom had gloves like Hepburn’s, too, which she wore sometimes when she dolled up in long dresses with short sleeves and went out with Dad, buttoned up tight in one of those tuxedos with the ruffled shirts, for the annual dental association ball. But she kept the real evening gloves stowed in a shoe box at the top of her closet behind some crumbling family photo albums and we couldn’t reach them. So we made do with the kitchen gloves – not that she ever thanked us for the substitution.

Pony Girl pulls on her kitchen gloves, bringing me back to attention as she wrestles the cuffs right up to her elbows, the rubber cracking against her funny bone, just like you did when you were pretending to be Audrey Hepburn. No giggling now, though.

‘Get undressed,’ she demands.

I raise my eyes to Mark and Leroy. That hint of a smile is still break-dancing around Leroy’s mouth and it seems to have spread like a yawn to Mark as well. I’d like to rub those smarmy grins off their faces with an eraser the size of a double-decker bus. I’ve never undressed in front of a boy in my life. Except for you, of course, but that’s not the same. Not even Dad has seen me naked since I was maybe six.

Pony Girl follows my gaze and now she’s grinning too. ‘Feeling shy, are we?’ She crosses to the door and kicks it shut, the two fools jumping back just in time to avoid sore noses. ‘Right, but remember, they’re just on the other side so try anything funny and they’ll be in here like that.’ She tries to snap her fingers but can’t with the gloves on so she claps her hands together instead, creating a dull plop of a sound.

I crouch down to unbuckle my Mary Janes. I want to step out of them gingerly, but my feet have been sweating and, without any hose, my soles have stuck. I pry each shoe off with the toes of my spare foot. Pony Girl’s impatient and nags me to ‘hurry up already’ as she drums her rubberised fingers together. My tartan skirt falls off as soon as I unbutton it at the back. I have to roll your turtleneck up over my head, turning it inside out as I haul it loose. My hair, drawn through the too-tight neck, springs free from the shirt all staticky, like I poked my finger in a socket.

It takes me less than a minute until I’m standing in nothing but my bra and panties, my hands clasped at my belly.

‘Underwear too.’

I hesitate and Pony Girl rolls her eyes. ‘Underwear too!’ she shouts. ‘For fuck’s sake, don’t you people understand English. Howya think a strip-search works?’

I bite my lip and wriggle my arms up behind my back in search of the catch to my bra, but my fingers are shaking and I can’t disentangle the hooks from the eyes. I slip my arms out of the straps and twist the clip round to the front. Even seeing it, though, it takes me four attempts to undo both hooks. I slide my panties down next, hustling them past my knees and ankles, and deposit them on to the dusty carpet with the rest of my Sunday not-so best.

‘Spread ‘em – arms and legs.’ It’s just like on some TV police show, Cagney and Lacey maybe, the one with the lady cops. Except it’s longer now, more drawn out, more humiliating – and without clothes, of course.

She starts in my hair, raking roughly through it with her clumsy, kitchen-glove paws, then she pokes in my ears and I’m wondering how how how could I hide any contraband there and what do they mean by contraband anyway, what does it look like and why do they think I would have any? Then the gloves brush against my cheek.

I remember Mom used to get awful mad when she’d go to do the dishes and those kitchen gloves of hers weren’t there.

I close my eyes and feel the honeycombed grip of the right palm – or is it the left? – abrading my face. Gripped not for scrubbing faces but for holding on to plates, holding on even when they’re wet and slippery.

‘Open your mouth.’

And I open my mouth and in slips a sheathed forefinger, probing my gums and my incisors and molars, pushing down my tongue, poking into my tonsils – or not the tonsils, but that dangly doohicky at the back, the cartoony bit they always show flapping about in Popeye when Olive Oyl opens her trap big enough to swallow the screen and lets rip with an almighty screecher.

Our mother also hated it when somehow we’d accidentally puncture one of those gloves, though I always reckoned it was more likely to be the fork tines than our little hands that were to blame.

Pony Girl’s kitchen-glove thumb is clamped over my nose and I’m inhaling the rubber that smells like balloons and tastes like them, too, this glove in my mouth, tasting like after we’ve been blowing up birthday balloons all afternoon, like we did for our tenth birthday party when all the kids from school came. And I wonder if this is what a condom smells like and tastes like, and I swear I don’t know for myself but I imagine it must be because it’s called a rubber too. The finger is out of my mouth and I have somehow managed to avoid throwing up again.

Whatever the cause, if there was a hole in those rubber kitchen gloves, the ones packed away beneath the sink, the corrosive soap and grime could seep right into your bones and it was as bad as not wearing any gloves at all, according to our mother.

Pony Girl’s finger is trailing my own spit down my cheek and around my neck and down. And I’m wondering what exactly it is that I’ve just had in my mouth, just exactly how many strip-searches these gloves have been a party to and just how exactly do they clean them afterwards? And maybe I am going to be sick on second thoughts.

Our mother always wore kitchen gloves. Up until our family got a dishwasher, anyway, which it was our job to load and unload.

Pony Girl’s rubberised finger is wet and slipping down my sternum, ringing round my neck and scooping under my armpits where usually I’m ticklish. And I’m thinking if maybe I laugh now she’ll stop, if maybe I pretend we’re playing a game to see who’s the most ticklish, it’ll startle her and she won’t be able to go on. But she does go on.

Then we got a cleaner too, as well as the dishwasher. The cleaner, she was named Marjorie. She came in twice a week, so Mom didn’t even have to wear the kitchen gloves for handling the mop or scouring the countertops or anything.

Pony Girl’s finger is snailing down my arm and checking under my fingernails for contraband – what contraband, how small is contraband, how microscopic does contraband come? – and then it’s back circling my waist and skidding down my stomach and then…

I am not going to scream or pee or flinch or cry or sneeze or plead – and then it is delving deep into my pubic hair, down and down and beyond.

Our mother still has lovely soft hands.

My eyes are closed.

And Mommy, I swear I’m a virgin.