Читать книгу Come Clean - Terri Paddock - Страница 7

CHAPTER TWO

Оглавление‘Where the hell are we going?’

Mom winds down her lipstick, careful not to catch the edge – she must be wearing about 112 coats by now – and she replaces the cap. ‘To the mall, of course.’

I swore – said hell to our parents as loud as you please and she didn’t bat an eye. I clutch my hands together, squeeze hard till all I can feel is bone. ‘What’s going on, Mother?’

‘After we finish the errands, maybe we can go to that new frozen yoghurt stand. It’s a funny concept, isn’t it? Frozen yoghurt? I never have liked yoghurt, I imagine there aren’t many people who’d claim to be yoghurt fans. Just the thought of it, just the word – yoh-gert. It’s a funny sounding word, foreign sounding, rather unpleasant, a funny food. But freeze the stuff, and people can’t get enough, you’ve got a craze on your hands. Amazing. And they do have such inventive flavours, don’t they? You’d like that, wouldn’t you, Justine? Pay a visit to the frozen yoghurt stand? We can get one of those waffle cones with the sprinkles on top. You’d like that.’

‘The yoghurt stand is at the other mall.’

She brushes nonexistent hair out of her eyes and flicks her visor mirror closed so I can’t see her face any more. ‘I’m sure they’ll have one at this mall, too.’

‘We’re not going to the mall, Mom. You know we’re not.’ My voice rises. The 7-Eleven slides past our open windows, the Hardee’s with the kiddies’ playground, the David’s Son motorcycle repair shop, the Green Valley block of low-rent town houses. ‘Why are you going on about the damn mall?’

‘Of course we’re going to the mall. We’re going to the mall to do some errands.’

‘What errands?’

‘What errands? Oh, you know, the usual things.’

‘I don’t know.’

Mom hesitates. ‘Well, we’ve got to go to the dry cleaners for one. And, then there’s the, uh, we’ve got to stop off at JC Penney’s because I need some blue thread for my sewing kit. And, well, while we’re there we should probably buy you some new pantyhose because you don’t appear to have a pair left to cover yourself with. And—’

‘Mom, there are no errands.’

‘Of course there are, why else would we be going to the mall?’

‘Stop it!’ I snap, trying desperately to retrace the route in my head, in case it comes to that. ‘That mall closed down over a month ago. There is no Penney’s, no yoghurt stand. They’re all shut.’ Cindy will have to steal her sister’s car or get Lloyd to drive. And she’ll need directions. You get on to the interstate heading north, I’ll say. Then how far do you go? What exit do you take? Is it a left or a right after the lights? How many miles do you drive? How many minutes? Look for the Shrimp Shack, the Shrimp Shack’s the marker.

Our mother’s pint-sized head moves about in juttery starts the way it does, like a bird. Tilting from side to side, bobbing down repeatedly as she inspects her lap, her cuticles, the contents of her purse. Peck, peck.

‘Mom. Where are we going?’

She punches Dad in the arm. ‘Jeff, why don’t you say something? Am I the only one here?’ She punches him harder. ‘Jeff, say something dammit!’

Our mother swears this time. Our mother never swears.

Maybe I should jump. How bad could it hurt after all? We can’t be going more than 35 mph. I will my hand to the door, my fingers glance the handle. Just yank then tuck and dive, like a gymnastic exercise that Mr Zarrow or Ms Loy or whoever taught us in PE class, nothing more. I screw up my eyes and squint at the tarmac, whizzing by. It’s hard, black, gravelly. No.

Dad slams the blinker and turns into that road. There’s no reason to say or do anything now. I cast about frantically for a road sign, but can’t locate one. Why don’t I ever know the names of roads? Warehouses flank us on either side. Strictly business trade. Look for the warehouses, I’ll say, there’s the Caterpillar tractor warehouse, the Billy’s Printing Supplies warehouse, the Dutch Tulips warehouse. Half a dozen others, all locked up, Sunday-quiet and stacked full of bulbs, books or heavy farm equipment. All corrugated iron and identical from the outside except for the choice of potted shrubbery, the executives’ initials on the VIP parking spaces, the company logos.

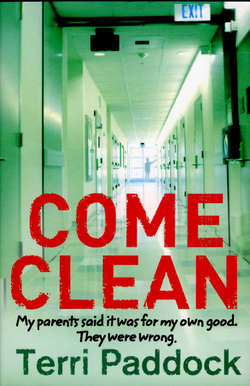

Only one warehouse is logo-free. It’s even more nondescript than the rest. This is where we’re going. Of course it is. No logos, no shrubbery, no signs, no initialled spaces. But it is open for business. There’s a smattering of cars in the front lot and I can see lights and the manned reception desk through the glass of the double doors. Dad eases into an empty space a few yards from the entrance, kills the engine and leaves the keys dangling in the ignition. The fob – in the shape of a miniature, but perfectly formed, set of dentures – knocks against the steering column.

My knuckles are white and taut, my veins braided like blue-coloured macramé beneath the surface of my skin.

Dad lumbers out of the car. ‘I’ll go and tell them we’re here.’

Mom keeps nodding even after he’s gone and out of sight. She fishes in her purse for Tic Tacs: I can hear mints clattering against plastic.

‘What’s going on, Mom? Tell me. Please.’

‘It is cold, isn’t it? I think we ought to roll the windows up now, don’t you? I just hate driving with the windows down.’ She leans over and notches the key enough to power the internal electrics then presses fingers on the automatic up-buttons for all four windows. The planes of glass hum until we’re sealed in.

‘That’s better, isn’t it? I think so, too.’

‘Why are we here?’

‘Tic Tac, Justine?’ She rattles the box.

Laughter springs up within me even as my eyes wobble. I unfasten my seat belt. ‘This is no time for mints, Mom. Listen, I know I was bad last night, but it was just once. I was – was…stupid. I promise, Mom. It’ll never happen again. Can we go home now? Please.’

‘Oh. That’s right, you’re thirsty. You don’t want a mint, you want some water. How silly of me. Let me go get you a glass.’

‘Are you listening to me, Mom?’

‘Certainly, Justine. Mommy’ll bring you some nice cold water.’

She snatches the dentured key ring and darts into the building after Dad. Probably I should make a run for it then and there. But, like our parents, I’m not thinking clearly. We all need a chance to come to our senses.

By the time they return with another woman – and without any water – I’ve thumped all the car locks down. Our father realises this when he tries to open my door.

‘Open the door, Justine.’

I pretend I’m stone. Like when we were little and used to play statues.

‘I said, open the door.’ Ferociously, he jiggles the outer handle. ‘Helen, the keys. Where are the keys?’

Our mother delves back into her handbag. The bag is on the small side and it’s a big ring of keys, but they appear to have gone missing nonetheless. Her hands tremble, like my own. One by one, she removes the familiar purse contents and places them on the kerb. When the purse is empty, Dad seizes it from her, rips the lining pockets inside out, tips the whole thing upside down and shakes it, lint and stray pennies go flying.

Then Mom discovers the keys in her coat pocket.

Dad brandishes the dentures fob like a mad prison warden. The keys for the Volvo jingle heavily against those for the house, which domino the ones for the practice, the spare set for Mom’s VW and the little skeleton one for the cabinet where he stashes the Novocaine and other anaesthetics. ‘We’ve got the keys, Justine.’

‘I can see that, Dad,’ I holler.

Still I don’t open the door. Dad marches to the driver’s door and inserts the appropriate key in the lock. The button pops up. He grins triumphantly, but I pound the button back down quicker than he can lift the handle. His grin turns to grimace. After a few more tries, me punching the button down each time, he scurries round to the passenger side. I’m there before him too and we rerun the same routine.

‘Helen, get the spare keys.’

Mom stands, flummoxed, with her purse disembowelled all over the pavement.

‘Where are the spares, Helen?’

‘In the key cabinet, Jeff. At home.’

Dad removes his tie and circles the car a few more times, until he’s panting. That’s when the other woman steps in.

She places her hand on his elbow. ‘I don’t think that’s necessary, Mr Ziegler.’ She’s pretending to talk to our dad, but her eyes are trained on me so I glare straight back. ‘Justine knows she can’t stay in there for ever. She’ll come out when she’s ready.’

I grit my teeth. I’m not sure whether or not I’m scared shitless or angry as hell. I bead up my eyes and fix them on her. Her own eyes – small, grey and widely set – hold my gaze. She’s nearly as tall as Dad and there’s too much of her body, too tall, too wide, too much. Around her neck hang two cords. At the end of one is a discus of keys, fobless and even more crowded than Dad’s; at the end of the other, a whistle.

I recognise this woman. Her name is…Hilary, I think. I’m pretty sure she’s the director of this place, the big cheese. I don’t know her last name – they never use last names – but I know her. She sat in on my sibling interview soon after you were admitted. Your intake, that’s what they called it. Barely uttered a word then, just watched me like she’s watching me now. I didn’t like her. Didn’t like her then, don’t like her now. I would say hate, but Mom told us never to say you hate on first impressions. Hate’s a thing that needs time to grow.

Ten minutes pass, maybe less, maybe more. I press the spot on my forehead just above the bridge of my nose until I glimpse stars. Twenty minutes. I unbutton my coat. Thirty minutes. There’s no air in here. Forty minutes. The smell from the vomit is horrible. Forty-five minutes. The smell’s overpowering, it flavours the air. I pinch my nose and take short, sharp, shallow breaths so I don’t have to taste the wretched stuff all over again. Fifty minutes, it must be fifty minutes. I consult my Swatch for the 2,367th time. I’m hyperventilating, my head is ratta-tat-tatting. I may pass out. If I pass out, they’ll get me.

What would you do in this situation?

An hour later, I open my door and puke at Hilary’s feet. She doesn’t move, just blows her whistle until four new feet bound into my field of vision.

‘Very good, Justine. Now you can accompany us inside of your own accord or Mark and Leroy can assist you.’

I raise my eyes to Mark and Leroy who are standing, stonyfaced, legs apart, arms folded, shoulders swelling. They should be visiting college football recruiters, and arguing with our dad about who’s likely to make it to next year’s Rose Bowl, not witnessing me wring my guts out.

‘Your choice. What’s it going to be?’