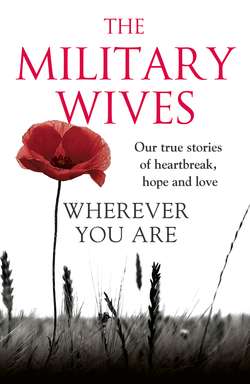

Читать книгу Wherever You Are: The Military Wives: Our true stories of heartbreak, hope and love - The Wives Military - Страница 10

ОглавлениеNicky Scott

If anyone ought to have been prepared for life as a military wife, it’s me. I was in the army myself; I took my career seriously and rose to be a sergeant. But it’s still different being a wife.

I joined up when I was 27, after a career working for Boots. I felt my life was at a crossroads. I’d had a seven-year relationship that had ended, and I wanted a challenge. I went to an army recruiting office near my family home in Snowdonia to make enquiries, just on impulse. Next thing, I was in.

After basic training I went to Germany in the Adjutant General’s Corps, which looks after personnel and admin for the army. I was on my own in a strange country, so I had to pull my confidence out of the hat. You can’t be shy and hide away. So from then on I was ‘the crazy Welsh woman’. The scary moment was when I was told after six months that I was going to Kosovo, as a military clerk looking after 110 men. We were thin on the ground and I had to do other duties, like being on guard, carrying a rifle. I couldn’t believe that a year earlier I was serving in Boots …

It was after about two and a half years that I met George, who is in the Royal Engineers, in the NAAFI bar at Osnabruck, and we quickly became close. Our first separation was when George deployed to Bosnia, which was heart-wrenching. Saying goodbye was weird, even though I was in the military myself. He’s my soulmate, and I think we both knew that from the beginning.

But we had to get used to separations very quickly, because a couple of weeks later I went back to Kosovo. We were both in the Balkans, but the only way we could speak to each other was to ring the UK and then get put through. It was difficult and we were lucky if we managed to speak once a week, but we could write blueys.

When I got back to Germany I was really ill. I was diagnosed with endometriosis, and I needed treatment. A German doctor told me rather brutally that I would never have children. It was a terrible blow.

George had been married before but he had no children. We knew we wanted to be together, but our future looked really weird without children, and it was a massive disappointment for both of us. It drew us very close together, especially as we were so far away from our families. We only had each other, and we decided to concentrate on our army careers.

Of course, after that news, we didn’t take any precautions. When we were both due to deploy to Oman, we were sent along to the medical centre for the jabs we needed. The medics did a pregnancy test because one of the injections affects an unborn foetus. I nearly fell on the floor when they told me I was pregnant. George was outside in a minibus with some of the others who were deploying. One of the staff brought him in and we had a crazy moment. We couldn’t tell anybody, because it was very early days, so we couldn’t show any emotion until we were on our own.

George was elated: it was a moment he didn’t think he would ever see. We’d settled in our minds that it would just be the two of us, two single soldiers, far away from home. We’d made our little life round that. We were so thrilled.

George went to Oman, returning two weeks before Georgina was born, which was lucky for him, as he missed all the pregnancy hormones. I didn’t give up work; I was even riding my motorbike until I was six months pregnant. It was hard being on my own so far from everyone, but if you are an army lady you just get on with it. My dad drove out to Germany to take me back to Wales for the birth, because he said he wasn’t having a grandchild born in Germany.

We got married five weeks after Georgina was born. I’d been trying to arrange the wedding from Germany, but it was complicated, with George’s family in Glasgow and mine in Wales, him in Oman and me in Germany. But we needed to get married so that I could get a decent-sized married quarter.

After maternity leave I asked for a posting near my family in North Wales, because my dad had been diagnosed with cancer. I went to Chester, which was as near as they could get me. George was out in Afghanistan and that was the most stressful time of my life, being a single mum with a tiny baby, my dad dying and George in Afghanistan. Also, I didn’t realise it, but during George’s R & R I’d got pregnant again. As I’d never had a normal menstrual cycle I didn’t notice anything, and I only put on half a stone, so again it was a lovely surprise. The sad thing is my dad died three weeks before Isla was born.

We moved to Kent, which was the only posting we could get together, and after a year’s maternity leave I went back to work. Then we moved to Wiltshire, for George to be based at Tidworth, while I had a post at Bulford.

After paying nursery costs I had £200 left from my wages every month. It was crazy, but I still loved my job. It was hard to be away from the children, but they were well looked after, and it was good for them to mix with other children. We were both sergeants by this time, but I always tell him I’m the boss at home.

It’s a strange life, moving from home to home all the time, and having to make friends wherever you go. It’s made me wary of making really good friends, because the minute you get close, they move somewhere else, or you do. You make lots of acquaintances, and occasionally some real friends, but then you face having to say goodbye all the time.

I left the army after 11 years, after Georgina, who was nearly six, said to me, ‘Why aren’t you taking me to school like the other mummies?’ George was away in Afghanistan, and I realised how hard it was for her, now that she was a bit older, to have her daddy away and her mummy working full time. I was in a job where I dealt with discharge papers, so I filled out my own paperwork. I didn’t tell George immediately, because he was in the thick of it, on the front line, and I didn’t want to distract him. But he was really happy when I did tell him. He was surprised I hadn’t done it sooner.

That was a strange time: my first proper experience of being a military wife. I went into myself a bit, put on weight, didn’t take any notice of myself. I put everything into the children, who loved having Mummy at home. But when they were both in full-time school I took another job, this time as a civilian working for the RAF, to keep myself busy and give me a bit of a challenge. It brought me back out of my shell. I’d really tasted the loneliness of being a military wife. I’m very strong, and if it could affect me like that, I know some women must be even harder hit by it.

By the time we moved again, to Chivenor in 2010, I was myself again; I’d got my sense of identity back. But when we got here I knew nobody, I didn’t have a job, my mood dropped and I put on even more weight. We’ve always been quite lucky with married quarters until we got here. We’ve not had the best, but some people have had far worse. You learn to fight for normal things, like getting the cooker working. The house we had in Tidworth was great but when we moved here it was a horror story. The place was infested with dog fleas, and one of my daughters got infected and nearly ended up in hospital. The house had to be fumigated three times, and all the carpets ripped out. George was getting ready to go to Afghan and I was having to fight to get our house up to a basic standard of cleanliness. It was a low, low time.

Pre-deployment is always a bad time, for everyone. If a marriage is going to break up, it would be at pre-deployment. You both need to be very strong to get through. One day you are a normal family; the next you have been told the dates of the tour that’s coming up, and your emotions kick in. You feel you have to do lots of things with the kids, because you may never do them again. Then afterwards you think: Why did we spend all our money doing that? It’s great to go out for a big slap-up family meal, but next day you find out that the car needs fixing.

As it gets closer, he’s not interested in family life. He can’t be there for us, because of the nature of what he’s doing. He’s now a WO2 and he was very stressed out during his last pre-deployment. I understand, but it’s hard. The children don’t understand, and it’s much harder for them. You have to put a front on the whole time, and you are worn out before he has gone.

During George’s last pre-deployment we had lots of family chats about what Daddy is going to do, what he’s going to wear, how many letters we can send. We planned what we would put in the boxes to send out to him. But I knew they were feeling it. Georgina, who was nine at the time, didn’t sleep much in the month before he left. Isla, who was seven, understood more than she had ever done when he’d been away before. It was hard keeping them steady. You can’t plan ahead, because you don’t know what life will be like in a year’s time. I protected them by switching the TV news off. I didn’t lie to them, but I just fed them the information I felt they could cope with.

We’ve learnt how to handle R & R, but it’s not always easy. The important thing is to get it late in the tour – get the worst of the tour over. Then we get away and pack things in. We live for the moment while he’s here, scooping the kids up and going to somewhere like Alton Towers. We both think that we’d be stupid not to enjoy it. But George also knows he can talk army to me, to get it out of his system. We don’t do it in front of the kids, but when we are together he can go over it all; I have my own take on it, and can join in. We constantly chat about what is going on out there.

When he goes back after R & R there’s a very low point. Even though he only had five weeks left to do last time, those weeks seemed to go very slowly. At the back of your mind you know that bad things can happen right up to the last day.

What saved me during the last tour was the choir.