Читать книгу Houses and Gardens of Kyoto - Thomas Daniell - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеHouses and Gardens of Kyoto

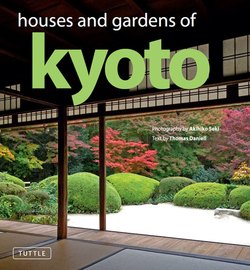

The central gate along the main garden path in the Okouchi Sanso estate.

Kyoto (or Heian-kyo, as the city was named at its founding by Emperor Kammu in 794) has been the birthplace—the incubator and crucible—of what is now considered to be quintessential Japanese culture. Afflicted by fires, wars, typhoons, floods, and earthquakes, Kyoto was razed and rebuilt more than once during its thousand years as the capital of Japan, yet it has also witnessed extraordinary flowerings of stylistic invention in literature and theater, ceramics and calligraphy, clothing and cuisine, and, not least, architecture and gardens. Much of this coalesced in the fifteenth century as what is now collectively known as higashiyama bunka (east mountain culture), during which the arts became suffused by the Zen-inspired aesthetic of wabi sabi (best translated as “impoverished beauty”): the chado tea ceremony, ikebana flower arrangement, sumi-e ink painting, no theater, and so on. “Flowering” is indeed the right word; the quintessential Kyoto aesthetic and attitude is known as hannari, literally “to become a flower.” The goal—for people as well as artifacts—is to be elegant yet understated, vibrant yet delicate, and always exquisitely sensitive to the nuances of one’s surroundings. For all the damage that has occurred over the centuries, for all the relentless modernization still taking place today, Kyoto remains a rich, inexhaustible archive of Japanese cultural history.

On the site of what was in prehistoric times an enormous lake, Kyoto occupies a flat plain surrounded by a horseshoe of mountains open to the south—a secluded locale and climate judged to have ideal geomantic properties. Emperor Kammu paid token compensation to the local farmers that he forced to relocate, and then had the city laid out on a regular gridiron pattern comprising walled blocks called cho, each 120 by 120 square meters (40 by 40 jo in the traditional measurement system). Influenced by city planning models from China, Kyoto was intended as an ideal city ex nihilo, a kind of urban mandala or matrix that placed the Emperor as an intermediary between the gods and the citizens. Inevitably, the purity of the original vision was compromised by topography and distorted by demographics. Over the ensuing centuries, the city has ebbed and flowed across the land, shifting eastward and regenerating in the aftermath of intermittent destruction. The present layout of Kyoto largely dates from the late sixteenth century, when the city was reconfigured and rebuilt by Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536–98), an extraordinary figure who rose from peasant origins to become the unifier and ruler of Japan after centuries of unrest and civil war.

The Kinkaku, or Golden Pavilion, is now part of Rokuon-ji temple, but was originally the Buddhist relic hall in the retirement villa of Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu.

Kyoto’s residential architecture evolved gradually from the founding of the city onward, and has been retrospectively classified into three main stylistic subdivisions: shinden zukuri (palace style), shoin zukuri (study style), and sukiya zukuri (tea house style). Rather than distinct historical stages, these form a continuous evolution of shared themes, following a general progression from a somewhat rigid and monumental formality to a more emancipated and sophisticated eclecticism. Not quite styles in the strict art-historical sense, they reflect particular lifestyles and social stratifications. Though primarily intended for the nobility and aristocracy, these three architectural types have also influenced the design of minka, the traditional vernacular houses of the general population. The minka may be broadly subdivided into urban dwellings (machiya townhouses, nagaya rowhouses, and yashiki detached manors) and rural dwellings (noka farmhouses, gyoka fisherfolk dwellings, and sanka mountain huts), all of which comprise wooden post-and-beam structures surfaced with a variety of natural materials.

Totsutotsusai, a sukiya -style eight-tatami chashitsu in the Konnichian estate of the Urasenke Tea School.

During the early Heian Period (794–1185), members of the aristocracy moved from all across the country to the new capital, where they built houses in the shinden style. Though commoners inhabited small subdivisions of a city block, a shinden dwelling often occupied an entire block, and in some cases two or even four blocks. Within perimeter fences made of tamped earth and capped with tiles, the northern half of the site would contain a roughly symmetrical array of pavilions linked by large sheltered corridors, arranged to contain a central courtyard that faced onto a garden and pond located to the south. The main building was the shinden itself, used for the daily life of the master of the house, with tainoya (secondary pavilions) for other family members and servants. The buildings lacked ceilings or internal partitions, their interior spaces articulated only by freestanding folding panels called byobu. The outer perimeters were closed by means of shitomido (detachable wooden panels), making the interiors completely dark at night and completely open to the environment during the day. Aside from a few movable tatami mats used for sleeping or sitting, the floors were wooden boards. No original shinden residences survive today, but their general characteristics are known from ancient picture scrolls and archaeological excavations. Some structures within the Kyoto Imperial Palace precinct (a reconstruction built in the nineteenth century) give a good sense of the shinden style, as does the Heian Jingu shrine (a partial, reduced-scale replica of the original Heiankyo Imperial Palace).

As effective political power shifted from the Imperial family to the samurai warriors during the Muromachi Period (1336–1573), samurai families adopted the courtly lifestyle manifested in the shinden style while adapting the dwellings to suit their own needs. As the samurai were expected to become monks upon their retirement, a number of distinctive elements intended to facilitate a life of scholarship appeared, such as the tokonoma (decorative alcove), chigaidana (staggered shelves), and tsukeshoin (built-in writing desk). These were initially contained in an annex that appeared as a component of the transitional shuden style, through which the shinden style evolved into the relatively opulent and formal shoin style of houses for both aristocrats and abbots. Made up of pavilions comprising an omoya (central volume) surrounded by hisashi (peripheral corridors), a shoin -style residence had a relatively free and asymmetric arrangement within its site. The floors became entirely covered with tatami mats, and wooden ceiling panels hid the roof beams. The cylindrical wooden pillars found in the shinden style were replaced with square pillars known as kakebashira, making it easier to divide rooms by installing a range of newly invented sliding fittings: shoji (translucent paper), fusuma (opaque paper), sugido (wooden panels made of Japanese cedar), and mairado (wooden panels with rows of horizontal wooden cross-pieces). The shikidai vestibule, with a wooden floor set at a slightly lower level than the tatami rooms, arose as the predecessor to the modern genkan entrance hall. The shoin style continued to develop over time, attaining its definitive form during the Edo Period (1603–1868) as exemplified by Kyoto’s Nijo Castle, residence of the Tokugawa shoguns.

An elevated walkway extending across the enclosed space of the Shihoshomen-no-niwa (Garden with Four Frontages) in Kanchi-in temple.

In Suisen-an, a renovated rural minka, daily life focuses on the irori, an open hearth set in the floor at the center of the main living room.

The next key development was the soan chashitsu (rustic tea house), a small hut for holding tea ceremonies, created during the Azuchi Momoyama Period (1573–1603). The custom of chanoyu (drinking tea) had been introduced to Japan from China many centuries earlier, and was refined in the Zen temples of Kyoto into a precise ritual: chado, the “way of tea.” The practice became fashionable among the aristocracy, who competed in the accumulation of expensive tea ceremony utensils from China and Korea, and gradually gained in popularity with the general public. The tea ceremony tended to be an elaborate performance before a large audience, held in a partitioned-off section of a shoin -style room decorated with an opulence that bordered on vulgarity. It was the Zen Buddhist priest Murata Shuko (1422–1502) who introduced the radical innovation of an intimate gathering in which the host himself served the tea, thus creating the basis for the tea ceremony as it is known today.

The broad veranda of Jodo-in, a tatchu (subtemple) of Byodo-in temple, established in the late fifteenth century.

The sixteenth century saw the appearance of a room solely used for tea ceremonies, generally with an area of yojohan (four and a half tatami mats, about 7.3 square meters), just enough to hold the host and a few guests. This became the prototype for the soan chashitsu, the design of which was perfected by the celebrated tea master Sen Rikyu (1522–91), chado advisor to Hideyoshi himself. In an explicit rejection of the flamboyance of tea ceremony practices among the aristocracy, the soan chashitsu is intended for a version of the tea ceremony known as wabicha, which emphasizes simplicity, humility, and frugality. Seemingly temporary huts with thatched roofs, wall surfaces of exposed dirt, and wooden elements left in their natural state, these tea houses deliberately recall the impoverished dwellings of ancient Buddhist hermits. While still using many of the elements found in shoin design—tatami mats, tokonoma alcoves, shoji screens—the designs emphasized idiosyncrasy and irregularity, assiduously avoiding repetition and standardization. The ostentatious Chinese implements were substituted with inexpensive, imperfect, everyday Japanese items, albeit selected with exquisite taste. Through an outgrowth of Zen Buddhist practices, the soan chashitsu was empty of religious icons, creating a condensed aesthetic experience of natural materials, their austerity and asperity enhanced by the subtle play of light and shadow.

In a sense, the tea ceremony is considered a form of Zen practice, as expressed in the phrase chazen ichimi: “tea and Zen have the same flavor.” Introverted and hermetic, the soan chashitsu is nevertheless inseparable from the garden in which it is located. The roji (dewy ground) path leading through the garden is intended as a transition from the prosaic world of everyday life to the poetic world of the tea ceremony. Tea gardens tend to be verdant, with overhanging leaves and mossy ground, though without the distraction of brightly colored flowers. Guests follow an artistically composed array of stepping stones—Rikyu stated that they should be 60 percent functional and 40 percent ornamental—passing a toro (stone lantern) and tsukubai (stone water basin) to arrive at the koshikake machiai waiting area. Having been welcomed by the host, guests pass through the tiny nijiriguchi entrance. The space inside also tended to be tiny—the single surviving example of a soan chashitsu believed to have been designed by Rikyu is only two tatami mats (3.2 square meters) in area. Called Taian, it was built in 1582 on the grounds of his residence in Kyoto, but later disassembled and rebuilt at Myoki-an temple, just south of the city.

A gold leaf-covered byobu (folding screen) standing in one of the guestrooms of Kinpyo, a renovated machiya.

The Botan-no-ma (Peony Room) of Daikaku-ji temple, in which eighteen fusuma panels have been covered with paintings of peonies.

The karesansui (dry landscape) garden adjacent to the large hall in Nanzen-ji incorporates the distant Higashiyama mountains as shakkei (borrowed scenery).

The understated eclecticism of the soan chashitsu influenced the next major shift in Kyoto’s residential architecture, the sukiya style (more properly called sukiya fu shoin zukuri: the shoin style as influenced by the sukiya). Used interchangeably with chashitsu as a name for the tea house itself, sukiya is an emancipated and idiosyncratic variation on the shoin style. The atmosphere is more relaxed, the spaces smaller, the ceilings lower, the elements thinner, the materials untreated, the compositions relatively uninhibited. To be sure, sukiya architecture often includes whimsical decorative elements at odds with the austere wabicha aesthetic, and rather than the isolated microcosm of the tea house, typical sukiya architecture tends to be open to, and integrated with, its environment; indeed, the surrounding garden should be regarded as a necessary complement to the building. The sukiya style reached its apotheosis with the Katsura Imperial Villa, built in the seventeenth century, but has dominated residential design right up until the modern period and continues to be popular today. While the vast majority of sukiya dwellings still retain some purely shoin -style spaces—the shoin rooms are for important occasions and guests, whereas the sukiya rooms are for daily life and friends—it is with the sukiya style that traditional Japanese architecture attained its fullest maturity and refinement. The underlying modular system of dimensionally coordinated timber frames and infill panels provides a disciplined framework for creations of extraordinary delicacy. Lightweight walls and sliding panels produce fluid, mutable interiors, while the peripheral engawa (veranda) spaces and their layers of lattices and screens enable a flexible integration of outside and inside. Suffused with soft light through mobile shoji panels and open ranma slots above the interior partitions, the predominantly rectilinear patterns that define each surface are accentuated by occasional irregular elements, such as the natural form of the tokobashira corner post in the tokonoma alcove.

While the suffix ya simply means “house,” the prefix suki has been written using various kanji characters across the centuries, phonetically identical but different in meaning. Initially suki used the kanji character , meaning “fondness,” and acclaimed aesthetes would be described as sukisha: people with a fine sense of assurance and discrimination in their aesthetic choices. Generally wealthy members of the aristocracy or nobility with time on their hands, sukisha were devoted to the full range of the arts, which were considered to reach a unified apotheosis in the tea ceremony and its associated implements and spaces. Thus a sukiya was a building designed not only according to personal taste, but according to the exceptional taste of a sukisha. During the Muromachi Period (1336–1573), suki came to be written using the two kanji characters, which are simply a reversal of the kanji for kisu ( “odd number”), thus evoking irregularity or eccentricity. Indeed, in contrast with the Chinese love of even numbers, and hence symmetry and balance, Japanese culture is pervaded by a preference for the asymmetry and tension implied by odd numbers. Gift giving in Japan entails odd-numbered amounts of money bound by cords with an odd number of strands, given on odd-numbered anniversaries. The shichi-go-san (seven-five-three) shrine visits are made by children of those ages to celebrate passage into each successive phase of childhood. The doubling of an odd number is even more auspicious: the gosekku (five seasonal festivals) are held on the first day of the first month, the third day of the third month, the fifth day of the fifth month, and so on. This predilection for odd numbers underlies all traditional Japanese aesthetics. A haiku poem, for example, comprises seventeen syllables divided 5/7/5, and waka classic verse comprises thirty-one syllables divided 5/7/5–7/7. The renowned Ryoan-ji stone garden contains three rock clusters, comprising three, five, and seven rocks respectively, and all fifteen can never be seen simultaneously—from any given viewpoint, at least one is hidden behind the others. Simultaneously insufficient and excessive, an odd number cannot be balanced or resolved without leaving a remainder—an intimation of the existence of something more than the immediately perceptible. It is this disquieting sense of incompletion that gives tension and dissonance to all the traditional arts, whether the laconic simplicity of haiku, the spontaneous black brush strokes on white paper in a sumi-e painting, the incongruous twisted branches in ikebana, or the irregular accents and subtle misalignments in sukiya architecture. Such serene yet precariously suspended compositions always rely on the intuition and imagination of the observer for their completion.

A calligraphy-covered byobu (folding screen) and ceramic vase on display in Iori Sujiya-cho, a renovated machiya.

Selected by Japanese photographer Akihiko Seki, this book contains a collection of houses in the widest sense of the word: exemplars, variations, and hybrids of the shinden, shoin, and sukiya styles, with buildings ranging from summer villas for the aristocracy to town-houses for ordinary citizens, from monumental Buddhist temples to insubstantial garden huts, and from personal homes to traditional inns. All have their related gardens, whether tsuboniwa (condensed courtyard gardens), kaiyushiki teien (picturesque stroll gardens), karesansui (“dry landscape”) stone gardens, shakkei (the “borrowed scenery” of a distant landscape), or some combination of these and other types. Each one is a fine example of traditional Kyoto house and garden design, yet to discuss the historical origins of this architecture is not as straightforward as it may seem. Take, for example, the gold leaf-clad Kinkaku (known in English as the Golden Pavilion), one of Kyoto’s most famous and spectacular structures. Built in 1397 as part of a retirement villa for Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu and later incorporated into the Zen Buddhist temple Rokuon-ji (otherwise known as Kinkaku-ji), it is thanks to buildings such as this one that Kyoto was mostly spared from damage during the Second World War. Though considered as a possible target for the atomic bomb that ultimately landed on Hiroshima, Kyoto was recognized as a city of such profound cultural importance that US Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson declared it to be “the one city that they must not bomb without my permission.” Yet throughout the war one of the young acolytes living at Rokuon-ji was longing for the bombs to land. He harbored a strange obsession with the Golden Pavilion that could only be consummated by seeing it burn down with him inside. When the war ended with the building still intact, the acolyte made its destruction his mission in life, plotting an act of simultaneous arson and suicide. He was half successful: in 1950 he burned the building to the ground, but lost his nerve and escaped the fire. Quickly arrested, tried, and jailed, he was found to be suffering from various mental and physical illnesses, and died within a few years. The Golden Pavilion, on the other hand, rose from the ashes: a gleaming replica was completed in 1955. There are conflicting opinions regarding the acolyte’s true motives (famously fictionalized in Mishima Yukio’s novel The Temple of the Golden Pavilion), but in any case the building you will see in Kyoto today is not the original Golden Pavilion. In fact, this was not even the first time it had been completely destroyed by fire, and like every wooden building in Japan it has been subject to frequent repair and constant replacement of parts over its lifetime. Very little of the structure has ever been “original” in any conventional sense. Yet, in the minds of the Japanese public, the current structure is indeed the real thing; it just happens to be made of new materials.

The karesansui (dry landscape) garden on the east side of Ryogin-an temple comprises nothing more than stones set in reddish granite gravel.

The perfectly maintained tsuboniwa (enclosed garden) in the Kinmata ryokan, visible from most of the rooms.

The narrow Ishibei-koji (Stone Wall Lane) is located in the south part of Gion, the historical geisha district of Kyoto.

This demonstrates something quite fundamental about people’s attitudes toward historical authenticity in Japan. Naturally, if the Parthenon were to be destroyed and rebuilt, it would be seen as a substitute for the lost original. In the West, ideas may change but substance should be eternal; in the East, it seems that the opposite is true. Indeed, much of the traditional architecture you will encounter in Kyoto today may be old in form but relatively new in substance. Made of fragile materials—wood, paper, bamboo, earth— subject to a humid climate and frequent natural disasters, these buildings require constant repair. The fabric of the city has its own languid metabolism, a pulse of ongoing construction and destruction, replication and renewal. Manifesting the paradoxical Japanese love of both the patinated and the pristine, these artifacts from the ancient past are suffused with the smell of freshly cut wood and newly laid tatami mats, surrounded by fastidiously manicured hedges and raked gravel. The houses and gardens of Kyoto remain ageless.

Perhaps the most common phrase to be found on a kakejiku (hanging scroll) in a tokonoma alcove is ichi go ichi e (“one occasion, one encounter”). The implication is that every moment is irreducibly unique. Above and beyond historical narratives and cultural intentions, the ineffable spaces, shadows, scents, and sounds of these houses and gardens are best experienced in all their sensual immediacy and intensity, right here and right now.

Interior of Gepparo tea house at Katsura Imperial Villa.