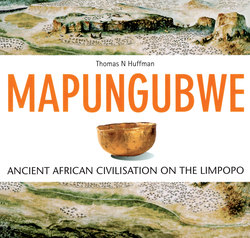

Читать книгу Mapungubwe - Thomas Huffmann - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеGEOLOGY AND CLIMATE

The Shashe-Limpopo basin lies in what geologists call the Limpopo Mobile Belt between two ancient continents, the Zimbabwe craton and the Kaapvaal craton (South Africa). Granite forms the two cratons to the north and south, while erosion over many millions of years has produced the sandstones in the basin. As the continents moved, cracks appeared in the earth’s crust, allowing magma to come up from the earth’s core to form basalt sheets and dolerite dykes. One impressive dyke standing near Mapungubwe looks like a man-made wall.

Over time, the Limpopo River in the centre of the belt changed course, creating the escarpment to the west of Mapungubwe. More recent fluvial terraces cover the valley floor. In the time of Mapungubwe, the Limpopo itself flowed permanently, but the Shashe was a river of sand with water underneath. When the Shashe occasionally floods, it acts as a dam wall and backs up the Limpopo for several kilometres. The short but narrow gorge downstream of the confluence enhances the dam effect, and depending on rainfall, flooding would have been a regular occurrence. In fact, during the Middle Iron Age, the Limpopo was the Nile of Southern Africa.

The climate would have supported dense forests with ilala palms (Hyphaene natalensis) alongside the riverbanks. Thoughthe forests have now mostly disappeared, the floodplains still support salt-bush (Salvadora angustifolia) where the soils overlie basalt, while mopane trees (Colophospermum mopane) grow elsewhere in the valley and on the plateau above.

All these natural features played a part in the rise of Mapungubwe.

Looking north across the Shashe-Limpopo confluence

Typical sandstone koppie (left) and dolerite dyke (right)