Читать книгу Mapungubwe - Thomas Huffmann - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

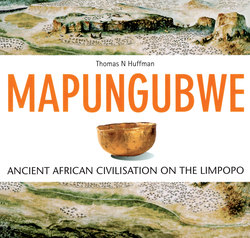

ОглавлениеSCHRODA

The capital

African farmers were absent from the Shashe-Limpopo basin between about AD 600 and 900, because the climate was not suitable. At this time, Zhizo people (named after their characteristic pottery)* lived in better-watered areas in southwest Zimbabwe and eastern Botswana. Some Zhizo people moved south from Zimbabwe in about AD 900 and established a settlement at Schroda, near the banks of the Limpopo. Cattle dung and domestic animal bones show that they herded cattle and small stock, while grindstones, the burnt remains of grain bins and the shapes and sizes of their pottery attest to farming. The size of the settlement suggests that some 300–500 people lived there.

Excavations in the chief’s area at Schroda, with the Limpopo in the background

Schroda – taken from the name of the form – was the largest Zhizo settlement in the basin at the time, which indicates that it was the capital. Throughout southern Africa, settlement size was related to male political power. As a rule, the chief was the wealthiest person in the chiefdom, accumulating more cattle than anyone else through court fines, forfeits, tributes, raids and the high bride price of his daughters. Because of this wealth, the chief had more wives, more fields, more followers and more court officials – and therefore the largest settlement.

*Different groups of people produced different pottery styles, and by convention, the people are named after the pottery. Pre-historic pottery styles are named after the first place they were found.

Figurines

In the recent past chiefs usually controlled the rites of passage in their societies, such as female initiations. In Southern Africa, female initiations often involved the use of figurines as props in lessons taught through metaphor and symbol during the school. Archaeological excavations at Schroda uncovered a large cache of unusual figurines that were probably used in a similar school. This cache includes animals, humans and creatures of fantasy. They were found next to the main cattle kraal: finely made domestic animals lay broken and discarded on one side of a wooden fence, while roughly made animals and fantasy creatures lay on the other. This division probably had something to do with the lessons. Generally speaking, the lessons would have covered such topics as the history of the group, various aspects of social organisation and proper moral behaviour.

Wild animals and fantasy creatures in the figurine cache at Schroda

Domestic animal figurines in the cache at Schroda

Elephants and settlements

Until a few years ago, archaeologists thought that Zhizo communities had moved into the Shashe-Limpopo basin because the climate had become wetter than it is today. Newer climatic evidence, however, shows that rainfall did not improve until the K2 period, around AD 1000. It was elephant ivory, not agriculture, that was the attraction. An ivory trade with the East African coast existed in Zimbabwe for about 100 years before Zhizo people entered the basin. As the thriving herds today demonstrate, the basin is prime elephant country, and elephants probably lived throughout the area.

The high number of elephants in the basin probably explains the distribution of Zhizo settlements. Most were located well away from the rivers and floodplains because otherwise elephants would have destroyed the fields. (Until recently, this was the problem with agriculture in the Maramani Communal Area across the river in Zimbabwe.) The artefacts from Schroda also demonstrate an ivory trade. Schroda, in fact, is the first settlement in the basin to yield a large amount of ivory working debris.

Distribution of Zhizo settlement in the basin. Most settlements were located some distance from good agricultural lands.

International trade

Besides ivory debris, excavations at Schroda also uncovered a large quantity of exotic glass beads. These beads show that the Indian Ocean ivory trade had reached Southern Africa by this time. Later Portuguese accounts describe how the trade followed the rhythms of the monsoons. Such goods as ivory, gold, rhino horn, leopard skins and iron were taken from the interior to coastal stations in Mozambique, such as Sofala (in what is now the Bazaruto area), where Arab/Swahili dhows transported them up the coast to the most powerful Arab/Swahili city, Mogadishu.

After the goods were taxed, traders sailed on the easterly monsoon winds to Arabia and India. There they exchanged the African goods for such items as glass beads, cotton and silk cloths, and glazed ceramics. On the reverse monsoon, the traders returned to Mogadishu, where they were taxed again, before sailing down the coast to Sofala to begin another cycle. Zhizo people controlled the Shashe-Limpopo portion of this trade for about 100 years.

Trade routes in the Indian Ocean network