Читать книгу Bent Street 4.1 - Tiffany Jones - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

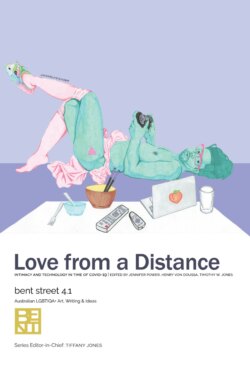

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеThe rise of the internet and digital technology has facilitated a new world of human connection. Never has it been so easy for people to speak across continents and timezones. Never has it been so commonplace for people to connect, often in quite intimate terms, with strangers. Phones, apps and chat rooms have facilitated new cultures of sex, dating and romance. Sex is instantly available online. Bodies are available. Love is available.

Arguably, queers were the great early adapters of digital dating. Grindr led the way on geo-locating hook up apps, extending the span of gay men’s sexual cultures across digital and physical space. Meanwhile the internet has enhanced queers’ opportunities to find their people, explore queer life and seek affirmation: perhaps before venturing into queer physical spaces, or at times when those spaces are not available.

In recent months, social lockdowns imposed by COVID-19 have made the role that new technologies play in human connection starkly obvious. In lockdown, most of us are living an ever larger part of our lives through Zoom and Facetime. People communicate more often, and more intensely, though instant text messaging. Tech and human intimacy have become more palpably entwined than ever.

However, while digital communication may now be the most conspicuous form of technology facilitating and mediating human intimacy, technology has always been a collaborator in human relations – particularly when it comes to sex and intimacy. It is not only a smartphone, computer, or a new app that links people or shapes the nature of human connection. Often human attachments are produced in conjunction with much more mundane and quotidian technologies – coffee, alcohol, the kitchen table, the design of a sofa, the layout of a restaurant, the bus that drives us across town, the ring we wear on our finger.

Our aim for Bent Street 4.1 is to cast a broad lens on the role of technologies in shaping human intimacy with a nod to the impact of COVID-19. We asked people to reflect broadly on the role that technologies, both old and new, play in mediating human intimacy and shaping queer culture. The contributions we present in this issue do, indeed, show how technologies both constitute and are constituted by relational intimacies: what, as Lauren Berlant has said, are in reality, ‘the kinds of connections that impact on people, and on which they depend for living (if not “a life”)’. Many of the first-person accounts, the theoretical engagements and the visual arts in this issue, are articulations of technologies as ways out of isolation, ways of finding—or recognising—your crew and enacting belonging. The viewing of pornography for the first time on a Super 8 film among peers; the joining of two cans with string as a visual reminded that even as children we know technology can be playful and desire to mimic its connective potential; the medical technologies of the body that transform lives; the rise of sexbots and artificial intelligence in providing comfort; the excitement of building a new relationship via text message; and the use of GPS technologies in the delicate undulations of power in the dominance/submission relations of BDSM are all testament to the transformative potential of technology and desire in human becoming.

Jennifer Power, Henry von Doussa, Timothy W. Jones

July 2020