Читать книгу Bent Hope - Tim J Huff - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPrologue: The Hum of Hope

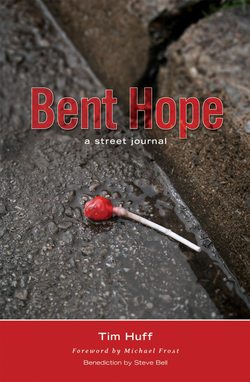

The stories in this book are stories of hope. Bent hope. But hope all the same. A couple occur outside of Toronto’s city limits and even across the Atlantic, but for the most part they are stories from a good city that unwittingly draws Canada’s largest pilgrimage of runaways, hideaways, castaways and throwaways, from small towns and large cities across the nation and even the United States. They are not stories of linear hope that point to magnificent and instant resolve. Not stories that look heavenward in anticipation of the sky cracking open and spilling angels to earth while harps play. But they are true stories of a miraculous finger-of-God hope that exists against all odds, only because the dear souls of these stories are survivors, and heroes and God’s own children—forced to seek out hope moment by moment. No more the stories of beggars, hookers and junkies than mine or yours should be.

The awkward truth can be packed into a single crass statement:

Either we are all beggars, hookers and junkies, or none of us are. There is no in-between.

At times—and for some, all the time—we all live with the cruel designations others have carelessly tattooed on us. Subjugated by what others think we are, and oppressed by what we feel stuck doing or being, while our hearts and minds long for release.

Every day I play the role of a beggar. I look to the charity of others, seemingly wanting something for nothing to feed my ego and the overwhelming need to belong. Every day I play the role of a hooker. I try to sell the words, ideas and actions I think might make me desirable to others, often against my own better judgment, in order to get the emotional validation I need to survive. And every day I play the role of a junkie. I feed my addictions, supplying relentless cravings with products, entertainment, daydreams and relationships that are bad for me. Thus, when rendered solely in vulgar human slang, I believe we are all beggars, hookers and junkies. And if raw humanity existed as the only gauge, I would know for certain that I am all of these.

But long before our biases and jaded opinions develop, long before we categorize people with labels and by issues, we all start in the same place, with the wide-eyed innocence and acceptance of childhood.

While this book is filled with gritty street stories, my desire is that no one would feel distant to its heartbeat. And so, it is in the tender memories of childhood that I begin. My own childhood comprehension of hope was similar to that of most children. Wishful and lucky—that’s hope. I was wrong.

It was while walking along the mom-forbidden railway tracks to elementary school that I best recall hope revealing itself to me in an entirely new way. I came across an orange tabby cat lying in a ball, thrown several body-lengths from the rails. Even as I approached from a distance, it was clear what had happened. One of the racing trains that crossed the rails had ended the life of someone’s dear pet. As a child, I approached it with that strange mix of emotions that stir inside most people as they view a calamity: the ridiculous and ugly combination of sorrow and curiosity.

Mesmerized, I stood over the cat’s motionless body, bending closer, and then closer again, for a more graphic take on the situation. After several minutes of sorrowful investigation, I stepped away, back towards the stiff weeds in the ditch. As I stood silent in my disbelief, I heard a soft wee voice crying out in two-tone notes. I tiptoed cautiously through the wild grass towards the tiny voice. As I headed further into the low brush I began to hear a second tiny voice singing in sad harmony. With little-boy steps in rubber-toed sneakers, I circled around until I found the source. Two tiny kittens. Small white faces peering up from green and gold thickets, calling out for the assurance of their protector and provider. But she would not answer. Beauty in tragedy. Tragedy in beauty.

I lifted them gently into my arms one by one, and as I did they called out louder and louder. They quivered and squirmed as I rocked them slowly—talking to myself all the while. Surely I could take them home. But what story could I make up? What story should I make up? I could not tell my mom and dad that I had been walking where I had been told so many times not to go. Even at a young age, I had a history of dangerous mischief along the railway tracks. And still, I thought—would they be so moved by the situation, and so caught up in these adorable creatures that they wouldn’t care and would overlook my disobedience? Better yet, would a white lie be justified in this case, all the same? I held the kittens for a long time and tried to hatch a plan. But soon enough I recognized that I was very late for school and was losing confidence in my ability to make myself the inventive storyteller who might get to keep the kittens.

So I set them back down in the thick blades of crabgrass and just stared at them. I stared with that look people get when their hearts tell them to do what’s right, and their heads tell them the cost is too high—that sustained look that eventually reveals that the head is self-serving enough to win the battle.

Then I began to ask their forgiveness. I promised them that something good would surely happen; an eight-year-old’s weak poke of hope. I even prayed for them, with a very earnest little boy’s “Hey God, let’s make a deal” prayer. And then I tried to walk away, my young soul weighted down with what can only be described as the hurt of hope.

Three or four steps at best. Halted by the chiming sounds of tiny kittens floating up from the wild grass and creeping weeds. I remember the hurt of hoping something wonderful would happen. Something magic. Something surprising and instant.

Then, from far off, just beneath the kitten calls, I heard a voice. Repetitive, monotone, and from a distance, sounding at first like a hum more than words.

“Oh no. Oh no. Oh no. Oh no.”

All of a sudden, cutting through the wide slats in a backyard fence, was a woman in a pale yellow apron. She stumbled down the steep mound, with her hands over her mouth, staring at her dead cat.

“But the kittens are right here,” I blurted out, gesturing enthusiastically towards the tall grass.

“Oh no. Oh no. Oh no. Oh no.” All these years later, I can still hear her responding with a trembling and somehow heroic, “Oh no.”

Her face was round and warm, even in her grand upset. Her small eyes darted from the motionless cat to the chirping twin kittens, to the mischievous little boy trying to stand invisible in front of her. A second survey of the images before her, and an all-knowing grown-up nod followed. She picked up the kittens lovingly and put one in each of the big pockets of her worn apron, reprimanded me sternly for being on the dangerous railway, turned sharply and shuffled her way up the hill, between the broken fence planks, and into her yard. All the while, fading out of sight with, “Oh no. Oh no. Oh no. Oh no,” until her voice was nothing more than a hum again.

It’s just a childhood story. Not unlike adventures that many boys and girls might recall. Still, the little-boy panic of not knowing what to do, or how to make things better, finds me time and time again all through my adulthood. I have left countless young people lost and alone in the frightening long grass, only steps away from imminent danger. I have avoided hundreds of mentally ill adults because I was late for a happier and simpler destination. I have justified staying uninvolved countless times, in countless situations, because the cost seemed too high. I have prayed, wished and begged God for miracles thousands of times on the streets, under bridges, in dark alleyways and in my own backyard. And I have lost by now what must literally count as years of sleep to the hurt of hope.

And still, in spite of myself, the hurt of hope, along with the anticipation of hope, and hope realized are all at the center of the lives I have been so honoured to be a part of on the streets.

The upset “oh no’s” of that busy homemaker scurrying about were a wonderful part of the music that day, for a little boy late for grade three. And even more so for the two tabby kittens that ended up nestled in her soft apron pockets. Yes, it was a glorious bit of music in the mind of child who has carried that tune in his head his entire life.

Surely hope is the music of the soul. Sometimes passionate and wild. Sometimes simple and melodic. Frequently out of tune and unrehearsed. And quite often found in the glorious “oh no’s” of an anxious loved one yearning to fix things and willing to do anything.

How profound and supernatural is it when it is more than even these. Somewhere in the miracle of survival, hope at its astounding best is life-giving. I have been blessed, shocked and severely scarred throughout my years on the street to see, hear and share in hope that is relentlessly life-giving and life-changing. The stories in the chapters that follow, both beautiful and tragic, bear witness to that.

Just as music wraps itself around a moment, a day or even a season, hope lifts, pauses, jolts and abounds in operatic proportions. The breathtaking anticipation of hope can be hypnotic as one senses the buds of health, progress or opportunity about to open. And hope realized is that grand inhale that fills the lungs in the final millisecond when someone escapes suffocation.

But it is the hurt of hope that is often the thorn too deep in the skin to dig out. In the midst of my own insecurities and hurts—the ones that have sucker-punched and taunted me throughout my life—I am floored by what I can only imagine are the overwhelming memories, hurts and abuses that grip my friends on the street. If I can recall 15 minutes of gentle sadness on the way to elementary school, how do the deviant sexual atrocities of an abusive father cripple a girl as she tries to grow up? How does the drunken fist of an angry parent stay with a boy as he stumbles into manhood? How do any of us carry on when our protectors have perished, like a cat struck by a train? When hope is not realized because of the horrors of abuse, isolation, and the loss of those who were supposed to love you, why would you continue to hope? When you have done all you can to find your way, and have only found abandonment, pain, loneliness and fear, why would you dare to hope? When the music of hope is drowned out by the noise of a death march, why not shut the music off forever?

Words do it no justice, perhaps because the hum of hope is gentle and healing. The purr of a harmonious calling. The early resonance of a soundtrack for binding up the brokenhearted in which the hurt of hope can be soothed.

But just as the splendor of music can be diminished by simple disregard and disrespect, hope can be grotesquely distorted and warped. Nothing squelches hope like an onlooker’s arrogance and pride. Nothing mugs hope like lukewarm pity. And nothing spoils hope like ignorance. All too often, those of us who have been spared the unthinkable tragedies of chronic abuse, isolation, addiction and rejection expect simple answers from those who have experienced these incredible hurts. “What happened? What will fix it? And what will it cost?” We want them to sum up the problems and give us the answers. Waiting in the wings for the answers we like, with timelines we deem reasonable. Answers we can claim and endorse when they fit our values and agendas, when in fact the true hum of hope includes the silent and spectacular victories of simply making it through another day.

Hidden in the cloak of daily survival and existence is where hope plays its most significant role. In the fatigue and discouragement of all-day-ness and every-day-ness—this is when hope is the anchor that keeps life from being swept away. We cannot wait until lives become epic, movie-ending creations. It’s so easy to exploit someone else’s life story by manipulating it into a nice neat package. A package we want boxed, bowed and presented without ever having been near their pain or the battle that, more often than not, secretly rages on. Counting on people to simply rise up and start over like cats with nine lives.

But cats only have one life, and hope doesn’t work that way. Real hope transcends all measurement only when we share in it. Not when we simply attempt to watch it magically occur in someone’s life, or wish for it from a distance, but when we participate in it. Not when we simply hear the humming, but when we hum along.

Hope, says Webster, is “The virtue by which a Christian looks with confidence for God’s grace in this world and glory in the next.”

My heart hears it like this:

Confidence: the reshaping of hope from a passive, wishful notion to its rightful place; the pitch-perfect bass line of hope’s song.

Grace: the sweet extension of hope borne out of the brokenness that each of us owns; the captivating melody of hope’s song.

Glory: the certainty that God has an astounding plan and celebration that reaches far beyond what we can even begin to fathom; the thrilling crescendo of hope’s song.

Confidence, grace and glory that include all boys and girls, men and women; built on the firm foundation of being in relationship with the life-giver. The very place where I believe God extended himself so that I could know for sure that hope is real was in a homeless baby born in a stable, who grew to promise the hope of abundant life, before he sacrificed his own. Abundant life is without a doubt the most undervalued and unappreciated promise ever made.

Even as I share these thoughts at the outset of this book, I fear two things. That those who call themselves Christians or “Jesus Followers” will assume this book is just for them. And that those who don’t will assume it is for someone else.

But this is not so. What follows is extended to all for consideration, deliberation and reflection: those who believe there is no God, those who hate God, those who struggle with God, those who believe in another one, and those who believe in him as Abba Father alike, convicted by an incredible remark made by Mahatma Gandhi: “If Christians would really live according to the teachings of Christ, found in the Bible, all of India would be Christian today.”

In spite of my own astounding inadequacies as a Christian and a human being, my faith is based solely on Jesus Christ. Not on Christians. Not a single one. And while I believe he was and is the Son of God, many of those I know who think he was just a great man can’t help but agree that he is a role model beyond compare.

Ultimately I believe in a God who is as relevant in the gutter as he is in the church. As miraculous in the ditch as he is in the chapel. And as beautiful in a rat-infested alleyway as he is in a glass cathedral. Anything else is hopeless. And nothing else makes sense.

I have no theological degrees or formal religious studies. I attended two community colleges in unrelated studies, and graduated from one. My beliefs and theories are born out of an education I had not anticipated as a young man: sneaking through crack-houses, weeping at hospital bedsides, strolling through alleyways after midnight, gigging at biker rallies, empathizing through prison bars, waiting at bus terminals, explaining myself in police stations, laughing beneath bridges, tripping through abandoned buildings, peeking into squats and shanties, leaning into gullies and ditches, serving at a camp for deaf children, living as a family man, and more than four decades of taking in Sunday mornings from the first five pews of a very decent, century-old church at the crossroads of a volatile community.

While I have occasionally altered names and locations to guard identities, these pages reveal snapshots of real times and places, bodies and faces, sonnets and odes that could easily be lost in the shadows of a population too hurried to notice. Fragmented glimpses of fragmented lives, where hope is anything but shiny and bright. Unpolished. Crushed. Twisted. Bent hope.

But somewhere in the wrinkles of every brief account, hope continues to hum. It continues to breathe. Often shallow breaths at best; even the faintest final breath, whispering one more note in the music of the soul.

Bent hope—inviting us all to be part of the music.