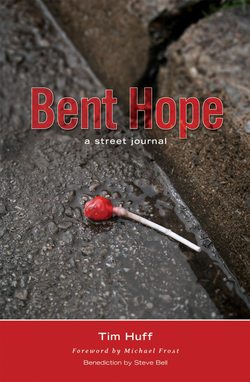

Читать книгу Bent Hope - Tim J Huff - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1. A Kid and a Coffee Cup: December 2005

“Hope is a passion for what is possible.”

I should think the last image in Søren Kierkegaard’s mind when he wrote this statement more than a century and a half ago was a panicked boy swimming in the sewer water of the most multicultural city in the world. And still the philosopher’s words were undeniably, even if unexpectedly, a tailor-made fit for the boy, the time and the place.

Thomas’s body was covered in sludge. Long dark trails of brown, clumps of black, and a glaze of translucent yellow. His shirt and socks were rolled in sopping balls lying next to his curled sneakers. Everything soaked. Everything shriveled and dirty. Ripe with the stench of waste and toxins. High on a flat rock, facing the unfamiliar pool below—a boy, just a boy, who had lost everything.

The summer of 2005 went on record as the hottest in decades. Showers and breezes were elusive at best. Far away from the mid-winter gasps of street sympathizers—“Oh, the cold, this cold, surely this deadly cold is the worst of all worsts!” That is the pebble in the shoe of every mind that stops to consider homelessness across Canada and in the northern United States. Around the beginning of February, people who ask me nothing about my homeless friends all year long will inevitably ask, “How do they survive? How do they bear it?” And no doubt, it takes the fortitude and will of a prize-winning bull to push through it.

But lost on most people, more often than not, is what it takes to survive the heat. Not just heat…but inner-city heat. Heat that not only comes from above, but from below. The sandwich heat that traps a body between the sky’s ball of fire at full volume from above and the hellish pavement and concrete from below. Endless baking pavement. Endless simmering concrete. Endless heat that refuses to let up. Captured in the day and stored in the solar tar by night.

This was the oppressive heat that drove Thomas to the Don River. One of the few stretches anywhere near the city core that reveals more green than grey. A seam through the city where a dull wind can find its way north and south, to and from Lake Ontario. And just enough murky water that when one squints his or her eyes a bit of elsewhere-ness can be imagined.

Not clean water. Certainly not healthy water. But water all the same. The Don has been abused like most urban rivers. Early in the twentieth century, industries such as paint factories and paper mills bled their waste into the river. As did more than 30 sewage treatment plants. Though much effort over the past few decades has gone into bettering the river and surrounding forest lines, even now, storm water is the primary source of the river’s pollution. It makes up nearly three-quarters of the river’s flow—and carries the waste migrating from freeways and driveways, backyards and truckyards. Untreated and directly into the waterway.

Still, for Thomas, there was plenty of leafy shade there. Mature trees and a sense of oxygen, non-existent in the core of the city. A bit of resistance to the conquering sun. Thomas was there, in the shade of a shrub, counting change from a coffee cup, when the sky was finally squeezed. Not a gentle squeeze. Certainly not an anticipated one. It was a shocking bear hug from behind. What one television weather anchor called a “spontaneous late-summer torrential macro-burst.” What simply felt like the inevitable result of a demolished dam hidden beyond the clouds. It didn’t rain in drops. Or even buckets. It came down in thick sheets of blinding, pounding rain. Apocalyptic rain, both unpredicted and unforgiving.

That same Don River runs in tandem to the Don Valley Parkway; the city’s only freeway running north and south. The rolling motorway dips deep near the river in several spots resulting in enormous flash-flood zones during severe downpours.

On this day, the rain simply had nowhere to go once it landed. In addition, the excess streamed into the natural basins from the ill-equipped sewer system. One of the great dim pools rose beneath the unofficial sky-high border to “downtown proper”; The Bloor Viaduct, known well for its history of suicide jumpers. Right where Thomas was.

The late night television news would ultimately show police on jet-skis and wave-runners, rescuing stranded drivers who had abandoned their submerged automobiles and shimmied onto concrete bulkheads. Homes some 20 kilometres north had basements under four, six, and eight feet of water. All of it charged in, had its tantrum, and hissy-fitted away without warning. Thomas, nestled in his remote pocket of wilderness, was caught off guard as much as any homeowner with satellite TV and access to weather forecasts by the minute. Heat, heat, heat…then with the city worn into submission, the clouds dropped a black curtain, flexed their muscles and said “gotcha!”

Somewhere between the mystery of it all and thanksgiving for cool relief, Thomas was besieged by the volume and incredible speed of the rising water. As crisp grass and dry soil softened and bloated the sloping hills, things began to float. Then bob, then swirl, then escape. Literally within minutes the river swelled and surged over the banks. And Thomas—young Thomas—panicked his way through the gloomy undertow on a desperate retrieval mission.

When I arrived long after the flood, Thomas was rolled in a ball on a dry rock slate, weeping. He had been a severe victim of the storm. As is usually the case for the forgotten few—the forgotten too-many—absent of both “home” and shelter. But his absence of everything caught me off guard. Every single thing. No backpack? No sleeping bag? So few items to maintain and save? Items so at-hand. As rapid as it was, it was not as though he was struck by a tidal wave. How? How did the boy who had so little now have nothing?

I was eager to ask. But I was not sure how to do it without sounding condescending. So, I just sat beside him. He wept and I just sat. For a long, long time. No words. Just the unnerving sense that there was far more to his tears than I knew.

“We can get stuff, new stuff, better stuff…whatever you need,” I babbled.

“Maybe this is a good time to try another route. Find you a place,” I continued, committed to the exhausting philosophy that long-term success in guiding young, severely broken lives into healthy adulthoods best, and almost always, starts with trust. Then moves to action. No matter how long that takes. The “absolute” I have indoctrinated myself with, and committed to, for better or worse.

But he heard none of it. He was not purposely ignoring me. Just crying so intensely that he literally could not hear me. So I waited while he sobbed, oblivious of my presence or the passing of time. My fierce curiosity and eagerness to intervene begrudgingly gave way to the better judgment of allowing him his time. His grief. His desperation.

Sirens echoed in and out of earshot forever as we sat side by side in silence. The awkward sounds of others getting help, others mattering, others inconvenienced.

Finally a long shaky sigh.

“My sister. My, my….”

Then more tears. More time. And several more sirens clearing their throats in the distance—heard and not seen. Everyone else getting fixed up.

“My sister was 14 when she left. Now how will I remember her? How will I find her?”

Thomas carried her picture in his fanny pack. She was two years younger than Thomas, but escaped their abusive home a year earlier than he did.

While the waters gobbled up all of his belongings, Thomas sacrificed it all for a search-and-rescue mission through the mire. Desperate for the eight-inch sack that housed the image of his sister.

His grief was shocking. His response was on par with that of a death, rather than the loss of a photograph. His heart broke open and his grieving words dribbled out.

“I was in the park. Waiting, just waiting! I should have been there! I should have been there!”

The critical history, in short, was this: while Thomas was waiting out his father’s rabid drunkenness—waiting for it to submit to a state of unconsciousness—his sister hit the unavoidable wall that comes with the fatigue of chronic abuse. She left a picture on Thomas’s bed as she snuck away. On the back of it she wrote:

I’ll die here. One day come and find me. I love you.

“How will I remember her? How will I find her? How…how…how…,” his weak body collapsed and he sprawled back, arched along the shiny rock face.

Who are the homeless?

Why are they like that?

Why don’t they just go home? Or go somewhere else?

They’re pathetic.

They’re ruining the city.

Delinquents. Lazy. Troublemakers.

Hideous.

After all of these years I have heard everything. Every question, every assertion, every concern, every query, every self-righteous and self-absorbed commentary. On the streets, in office buildings, at luncheons in church basements. But stuck in the moment, sitting beside soaking, stinking, exhausted, torn-apart, magnificent Thomas, all I wanted to do was hunt down every person I had ever heard spout out their uncompassionate ignorance and scream into their faces. Scream them away.

It happens often. And usually lasts until I bump into my own hypocrisy. When God allows it to drop-kick me off my feet. When I remember the guy on the crammed subway who bugged me by flopping around fast asleep in his seat. The girl at the convenience store I thought was kind of dopey because she was taking too long counting my change. The well-dressed kids bumming smokes outside the corner store that I shake my head at. Me. Me indeed. Me not embracing the very song I sing whenever I am asked about those I know on the street:

EVERY PERSON HAS THEIR OWN STORY.

To see muddy, messed-up Thomas sitting curbside, drinking from dented pop cans left half-full in trash bins, the quickest assumption made is that “he’s a problem.” He looks like a problem. Smells like a problem. For sure, he and all those like him are a problematic black eye on tourism. A problem for store owners, city council, family restaurants and fancy hotels. Some think he’s the mayor’s problem. Some think he’s the police’s problem. Provincial problem. Federal problem. Maybe he was the liquor store’s problem? The next-door neighbour who looked the other way’s problem? The teacher who didn’t report the obvious bruises’ problem? The downsizing employer who laid off his dad’s problem? The hospital that couldn’t cure his sick mom’s problem? The church at the end of his street’s problem? Messy, messed-up Thomas was the poster boy for pass-the-buck finger-pointing from every direction. He just thought he was a kid tired of getting beat up in his kitchen. Until he left. Then people made sure he knew what he really was. Not sure of whose. But sure of what.

A big problem!

But what about his story! His incredible story! It is his. The story of a heart that should be a brick but never hardened. The story of salvaging love and keeping promises. The story of broken bottles, broken limbs and a broken heart. His, his and his. All parts of his story. One of only two things that any of us possess that is truly priceless. One is our time. The other is our story. Each one one-of-a-kind. No less than the sleepy man on public transit, the sweet girl doing her best with simple mathematics or the wealthy teenagers looking for something more. The ones I jump to conclusions over. The good, the bad and the ugly. They all have a story. Their own story.

Only days later, Hurricane Katrina devastated the delta expanses while terrorizing the Northwest Gulf of Mexico and hypnotizing an entire continent. The worst natural disaster on record in the United States of America. Thomas and I watched it on CNN through an electronics store window, alarmed at the pictures and headlines. Unable to hear the reports, aghast at the images, we followed the headers at the top of the screen. Thomas was in tears. Not the same desperate tears of stabbing grief shed days earlier. Thoughtful, quiet tears.

Two days after Katrina’s assault on the deep south, Thomas spotted me coming up from the subway tunnel.

He ran towards me excitedly, “Tim, Tim, I need your help!”

At last! These are the words cherished most by me. Symbols of trust and signs of hope.

I nodded and shrugged my shoulders, “Sure!”

My mind began to race. Which shelter? Which contact? Maybe Evergreen’s Health Centre first? It’s the best. Maybe Covenant House next? A roof, a bed. I was readying my arsenal of help suggestions for baby step number one.

But before I could say a thing, he lifted his hand towards me. In it was a weathered old coffee cup. A Tim Horton’s coffee cup; the contemporary symbol of Canadiana from farm gates to skyscrapers, coast to coast. It was filled with change.

Dimes, pennies, nickels, quarters and the Canadian coins that make panhandling a tad more promising—one dollar “loonies” and two dollar “toonies.” They rattled and slid side-to-side just below the brim as he shook his hand proudly. I looked at him curiously as he waved the cup in front of me, gesturing for me to take it. He grinned wide, enjoying the suspense he held over me. His smile was toothy and bright, and his eyes were more alive than I had ever seen them.

Finally, with his other hand, he reached into his back pocket and pulled out a crumpled piece of ribbed cardboard, about the size of a shoebox top. He held it beside the coffee cup, only inches from my face.

With poetic beauty, in big scratchy letters created by the feverish dedication of scribbling a ballpoint back and forth over and over again, it read:

“For Katrina’s homeless, because it hurts to lose everything.”

The help he wanted? For me to take him to the bank. Just to make sure they would let him in so he could give it to the teller. That was it.

So I did. I took him. There was a long line. We waited for our turn, taking small steps every few minutes through the velvet-rope maze. The people in front of us and behind us kept a ridiculous distance away. Thomas pretended not to notice.

Finally we were next. He placed the cup on the counter in front of the teller. She looked down at it and wrinkled up her nose. Then looked up at him. Bewildered, she cocked her head and glanced at me. I tugged the sign out of Thomas’s back pocket and laid it on the counter beside the cup. The teller’s eyes welled up, and she smiled gently. She lifted the cup carefully with both hands and nodded.

“Can you add it to what’s been collected,” Thomas asked like a wide-eyed little boy.

“I will,” the teller promised softly. “Yes, I will.”

We turned. We walked away.

This is Thomas’s story. This is who Thomas is. Who he really is. This is who I need to be, who we all need to be. This is the personification of Kierkegaard’s brilliant and simple description of hope; a boy—a boy with nothing to his name—passionate about the possibility of making a difference. Regardless of the circumstances and obstacles.

The hot days grew cool, and the cool days grew cold. Thomas braved the change of seasons with a sense of newness. Something changed inside of him when his heart broke for others, regardless of his own plight. In his own brokenness he found his identity. Thomas found the best of who he was, and refused to ignore it. The best of who God had made him. An authentic, beautiful identity that people spend a lifetime looking for. One only ever found by sacrificing. No one needed the money in that coffee cup more than Thomas.

He took independent steps towards wellness. He began saying quirky and inspirational things like “God has a plan, y’know?” At first just to tease and appease me, for sure. But not much time passed before he said it with conviction. He secured a room all on his own. Then a better room and some financial assistance. Then some work. All without my help. God had led me to do but one important thing early in the process. That one thing was simply to be in the presence of Thomas’s astounding compassion and generosity. To receive the gift of knowing and being with Thomas. Ultimately, just to stand beside a poor boy in front of a total stranger while he gladly surrendered his tiny portion of wealth.

Thomas moved himself west just before Christmas. All with his own earned resources. He wanted to follow some hunches on his sister’s whereabouts.

But two weeks before he left I saw him sitting outside of Toronto’s world-class Hospital For Sick Children. I was surprised to see him there. It wasn’t his common turf, and he had not needed to wait on loose change for some time.

The snow was falling lightly, the moment fixed for Norman Rockwell. I stopped about two meters in front of Thomas when my eyes caught sight of the little sign resting beside the coffee cup in front of his crossed legs:

“Donations for Sick Kids. No one should ever lose a sister.”

It wasn’t about the money. He had his own. It was about giving other people the opportunity to participate in hope as he understood it. It was about Thomas’s own turnabout, what triggered it, and his wanting to make it contagious.

Some saw a beggar sitting outside the hospital that day. Some were sure they saw a scam. Many paid no mind as they trudged past a typical downtown object, a cityscape prop on par with a fire hydrant, park bench or trash can. Very few saw one made in the image of God. And none suspected a passion for what is possible.

Most people walking by, if they took notice at all, just saw a kid and a coffee cup.

But there was so much more.

There always is. Always.