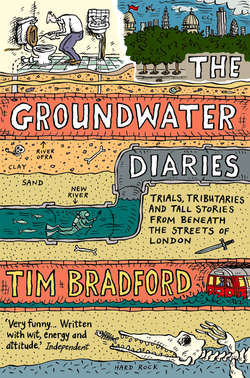

Читать книгу The Groundwater Diaries: Trials, Tributaries and Tall Stories from Beneath the Streets of London - Tim Bradford - Страница 10

3. Football, the Masons and the Military-Industrial Complex

Оглавление• Hackney Brook – Holloway to the River Lea

Arsenal – the football conspiracy – Beowulf – the weather – the Masons – Record Breakers – Holloway Road – Joe Meek – Freemasons – Arsenal – PeterJohnnyMick – Clissold Park – Abney Park cemetery – Salvation Army – Hackney – Hackney Downs – tower blocks – Hackney Wick – Occam’s shaving brush

Want to hear something amazing? If you look at a map of the rivers of London then place the major football stadiums over the top of it you’ll see that most of them are on, or next to, the routes of waterways. Does that make you come out all goosepimply like it did me? Well, here’s the hard facts that’ll send you rushing for the bog: Wembley – the Brent; Spurs – the Moselle; Chelsea – Counters Creek; Millwall – the Earl’s Sluice; Leyton Orient (sound of big barrel being scraped hard) – Dagenham Brook; Brentford – the Brent (too easy); Fulham – the Thames; Wimbledon – used to play near the banks of the Wandle; QPR – the exception that proves the rule; West Ham – OK, so that’s the end of my theory. But what of Arsenal?

I have a tatty old nineteenth-century Great Exhibition map1 on my wall at home on which the London of 150 years ago looks like a virulent bacteria on a petri dish. I have always liked saying 47 to friends, look, see where you live now? Well, look, it was once a … field. Then I’ll stand back with a self-satisfied expression while they shrug as if to say ‘Who gives a fuck, have you got any more wine?’ The Hackney Brook is marked on this map as a small stream near Wells Street in central Hackney. It also appears in various other sections, as a sewer along Gillespie Road, a small watercourse continuing off it towards Holloway and a river running from Stoke Newington to the start of Hackney, then stopping and continuing again around Hackney Wick towards the River Lea, before disappearing in a watery maze of cuts and artificial channels.2 But when I transferred the route of this little stream onto my A to Z it struck me that Highbury Stadium, Arsenal football ground, lay right on the course of the stream.

Arsenal are planning to move to another site at Ashburton Grove, half a mile away. This too lies above the Hackney Brook, at a point where two branches of it converge. What’s going on? Is there something about rivers that is good for football grounds? Water for the grass, perhaps? At one time they also wanted to move to an area behind St Pancras Station, the site of the Brill, a big pool near the River Fleet and, according to William Stukely, a pagan holy site.

And, while we’re at it, how did former manager Herbert Chapman manage to get the name of Gillespie Road tube changed to Arsenal in the thirties? Did he inform local council members that Dizzy Gillespie (who the street was named after) was, in fact, black and so all hell broke loose? How did Arsenal manage to get back into the top division after being relegated in 1913? Some sort of stitch up, no doubt. And how did they get hold of this prime land in North London? Did they channel the magical powers of the Hackney Brook using thirties superstar Cliff Bastin’s false teeth as dowsing rods?

A clue is in the club’s original name, from its origins in south London. The fact that it was called Woolwich Arsenal and was a works team is all the proof we need that the club is part, or at least was once a part, of the Military-Industrial Complex. They are the New World Order. Their colours – red shirts with white sleeves – are also simply a modern version of the tunics of the Knights Templar, forerunners of the Masons. Maybe their ground is situated near a stream because they need the presence of sacred spring water for their holy rituals. You know, pulling up their trousers and sticking the eye of a dead fish onto a slice of Dairylea cheese spread.

A search on the Internet for ‘Hackney Brook’ reveals only eleven matches, some of which are duplicates. One of the most interesting is a listings page of Masonic lodges in London. Lodge 7397 is the Hackney Brook Lodge, which meets in Clerkenwell on the fourth Monday of every fourth month. Why were they called Hackney Brook? Maybe they knew why the river had been buried. The Masons know all about all sorts of ‘hidden stuff’. Hidden stuff is why people join the Masons.

I love the idea of the lost rivers being somehow bound up in a mystical conspiracy. Maybe the rivers were pagan holy waters and the highly Christian Victorians wanted to bury the old beliefs for good and replace them with a new religion. Or what if developers – the Masons, the bloke with the big chin from the Barratt homes adverts (the one with the helicopter) – wanted new cheap land on which to build?

I have a dream about Highbury and Blackstock Road in the past, a semi-rural landscape of overlapping conduits and raised waterways, a Venice meets Spaghetti Junction. I am walking over deep crevasses covered by glass peppered with little red dots. Water flies through large glass tunnels, crisscrossing one way then another. Purple water froths over in a triumphal arch. It’s like some vaguely remembered scene from a sci-fi short story.

Arches are always triumphal, never defeatist. Why is that? Because, when you think about it, an arch is like a sad face. A triumphal face would be like an upturned arch. I email the dream to my new online dream analyst (‘Poppy’) to find out the truth.

An email arrives:

(In dippy American accent)

Hi Tim!

Dreaming of clear water is a sign of great good luck and prosperity, a dream of muddy water foretells sadness or sorry for the dreamer through hearing of an illness or death of someone he/she knows well. Dirty water warns of unscrupulous people who would bring you to ruin. All water dreams, other than clear, have a bad omen connected to them and should be studied carefully and taken as a true warning.

I had already noticed a pattern emerging in the California textured world of online dream doctors. Take money off punter then cut and paste a bit of text from a dream dictionary. After a couple of weeks I wrote back to Poppy but the email was returned. On her website was a 404 file not found. Perhaps the web police had raided Poppy’s dream surgery and found her in bed with a horse covered in fish scales.

After a bit of searching around I found a sensible new online dream doctor called Mike. He didn’t seem very New Age and replied promptly.

(Sensible Yorkshire accent)

I thank you so much for using our online Dream Diagnosis! I will interpret your dream as fast as possible. Thank you, and

God Bless,

Michael, Dream Analyst

A river called the Hackney Brook? You have to admit it’s a rubbish name. Some river names, like the Humber, Colne and Ouse, are thought to be pre-Celtic. The Thames is British in origin. Likewise Tee and Dee, and Avon. But the Hackney Brook? – the lazy fuckers just called it after Hackney. Didn’t they? Of course, mere streams and tributaries would not have been given the importance of big rivers. All the same, the Anglo-Saxons yet again manage to show how dour and unimaginative they can be. So what about Hackney? Where does that come from?

There are three possible origins for the name Hackney. Firstly, the word haccan is Anglo-Saxon for ‘to kill with a sword or axe, slash slash slash!’ and ‘ey’ means a river. Or it is a Viking word meaning ‘raised bit in marshland’ – perhaps because Hackney was always a well-watered area, with streams running into the River Lea. But the most likely explanation is that the area belonged to the Saxon chief, Hacka.

Proof for all this? For once I can offer some evidence. Here is an excerpt from the great Anglo-Saxon epic poem Beowulf. In this short section Hacka, the founder of Hackney, makes a brief appearance.

Came then from the moor

under the misty hills

Hacka stalking under

the weight of his river knowledge.

That Saxon pedant

planned to ensnare

the minds of men

in the high hall.

He strode under the clouds,

seeking Beowulf, to tell him

about the river he had found

near his new house.

Nor was it the first time he

had tried to name that stream.

And never in his life before

– or since –

did he find better luck!

For came then to the building

that Beowulf, full of wisdom.

(In E. L. Whisty voice)

‘Beo, there’s this river that runs

through my new gaff.

What should I call it?’

Quickly Beowulf’s brain moved

and he answered direct,

(in John Major voice)

‘Call your new home Hacka’s village.

And the stream shall be named

The Brook of Hacka’s village.’

‘That’s original and catchy, O great chief,’

said Hacka, much pleased. ‘Thanks a lot.’

As he went out, smiling.

He saw an evil demon in an angry mood

Pass in the other direction.

‘Evening, mate!’ said Hacka.

The demon had fire in his eyes.

That monster expected

to rip life from the body of each

one before morning came.

But Hacka didn’t notice –

He was too excited about his new river.

I never thought I’d turn into the sort of person who talked about the weather incessantly, but the rain round our way was definitely getting worse. Big plump drops, vertical sheeting, soft drizzle, aggressively cold splashes, wind-blown white scouring sleet, peppery eye-stinging bursts and, of course, dull, wet London showers.

Holes have been dug in the nearby streets and small Thames Water and Subterra signs have been erected. They are obviously doing ‘something’ to the underground rivers. Cutting a deal with them, perhaps, urging them to be quiet. Or diverting them further underground in case they snitch. Or converting the waters of the river into beer. I got through to Thames Water and tried to find someone responsible for underground rivers, but with no success. Then I’m back in a queue: ‘We are sorry to keep you. Your call is important to us. However, we are currently experiencing high call volumes. You are moving up the queue and your call will be answered as soon as possible. Thank you for your patience at this busy time.’

Floods. Snow. Christmas comes and goes. Under a young tree lies a charred pile of stuff – pieces of clothing, books, aerosol cans and a small stool. A pair of men’s shoes are still slightly smouldering. The aftermath of some apocalyptic festive break-up? Or perhaps a young graffiti-addicted accountant simply spontaneously combusted on his star-gazing stool while contemplating the sheer joy of life.

More lazy days in the library, looking at old maps of the area and the Hackney Brook valley. A book by a local historian, Jack Whitehead, shows the contours of the valley in 3D. The brook rose in two places, the main one at the foot of Crouch Hill, east of Holloway Road, with a smaller branch near the start of Liverpool Road.

Then my mind drifts and I stare at the faded chequerboard floor and listen to the beep of the book-checking computer thing, the cherchercher of the till, the murmur of African accents, the rumble of traffic going past the window. In Stokey library people eye each other up, but not in a good way – more ‘Errr, you’re walking along the lesbian crafts and hobbies section? You must be a poof.’

At last I find what I’ve been looking for. An old map, from some obscure US university, showing the course of the Hackney Brook in relation to the nearby New River and which corresponds with the old map from the Islington book that my neighbour lent me. It shows the rivers crossing over at a point parallel to the Stoke Newington ponds, about a quarter of a mile west. Thus ‘the Boarded River’ was the New River, kept at the correct gradient as it passed through the Hackney Brook valley and over the Hackney Brook. This is the point in the film where I turn to my glamorous assistant, as the Nazi hordes are waiting to pounce, and she kisses me in congratulation. I take off her glasses and realize she is actually quite beautiful. I then hand her a gun and say, ‘Do you know how to use this?’ Suddenly the door bursts open, she shoots five evil Nazis and we smash though a window and escape …

I also had a look at John Rocque’s famous map of London in the British Library (rolled up it looks like a bazooka). Rocque’s depiction of Hackney Brook is a little sketchy – he has it starting further east and north than its true course and doesn’t have it crossing Blackstock Road at all. This might have thrown me off course, but allied to various mistakes in the same area suggests that Rocque never actually visited Hackney and Stoke Newington. He was too scared. Probably got one of his mates to do it.

Mate: So there’s this little river. I’ve drawn it on the back of a beer-stained parchment for you.

Rocque: Tis very squiggly.

Mate: OK, if that’s your attitude why don’t you go and have a look at it?

Rocque: Ooh no, I’m, er, far too busy. And I’ve got a cold.

I had a vague notion of walking the route of the Hackney Brook and then all the other rivers and streams in London, then writing to the Guinness Book of Records and appearing on Record Breakers.

Me: Yes, well, you have to bear in mind the substrata of London and its alluvial plane. Back in the mists of time there blah blah blah …

Then the studio floor opens up and there’s an underground river. A little boat appears in the distance with a single oarsman and it’s Norris McWhirter and he’s holding a clipboard and tells the audience some factoids about the rivers. Then we listen to a tape of Roy Castle doing the unplugged version of ‘Dedication’ and the audience cheers.

It’s time to do some dowsing again. I buy a can of Tennent’s Super and walk across the zebra crossing at the bottom of Blackstock Road, over and over again. I don’t drink Special Brew so much as use it as a tool. I see myself as part of the same tradition as Carlos Castaneda. Whereas he got in touch with the spirit world through his use of Mexican psychoactive funguses, I buy cheap beer from Pricecutters in Highbury Vale and walk around muttering to myself, getting a clicking sound in my right knee (an old hurdling injury). I am also keen to reclaim these drinks from being the beverage of mad drunkards and to create a new form of Special Brew literature. Funnily enough, I found a book by Benjamin Clarke, a Victorian Hackney man who wrote a book called Glimpses of Ancient Hackney and Stoke Newington, in which he says that Hackney Brook used to be regarded as a river of beer. The Woolpack brewery, near Hackney Wick, churned out barrels of the sort of stuff that Londoners loved (and love) to drink – soapy mouthwash with no head. Discovering the alchemical secret of turning water into beer – it’s every man’s dream.

As my head buzzes pleasurably, I look up the road and see the river valley ahead of me. I’m ready to do the walk. But first I need a piss (beer into water reverse alchemy technique).

The northern branch of Hackney Brook apparently starts at Tollington Park, around Wray Crescent and Pine Grove. It’s just off Holloway Road, which is packed with people – dark-eyed lads with eighties jackets hawking tobacco; pale-faced chain-smoking girls with bandy legs and leggings tottering along with prams; huge-bellied tracksuit trouser blokes waddling from café to pub with a tabloid under their arm; Grand Victorian department stores turned into emporiums of second-hand electrical tat; eighties-style graffiti; students queuing at cash points; geezers flogging old office equipment piled high on the pavement. At no. 304 lived Joe Meek, the record producer of songs like ‘Telstar’, strange futuristic pop classics. Dang dang dong dong ding deng dang dung dooong. He must have been influenced by the strange atmosphere of this neighbourhood with its crazy adrenalin-fuelled rush of bodies, bumping against each other like electrons in matter, Oxford Street’s ugly sister.

I had been hoping to see some kind of plaque or ramblers’ guide at the start of the walk, possibly even a fountain bubbling with pure spring water. Instead I am faced with a large fenced-off mass of earth, a secret building site, with a lonely blue prefab building. Men with yellow hard hats stand around holding stuff – clipboards, balls of string, spanners, a spade. It’s a tried and tested workman’s trick. Hold something functional just in case the ‘boss’ happens to be driving past in his silver Jag and looks over. ‘Hmm, good to see Smithy is working hard with his ball of string.’

There are two ways of looking for a river’s source. You can do it the proper way with geologists, maps, digging equipment and people from Thames Water saying ‘please hold the line’. Or you can look for puddles. And right in the middle of this mass of dirt is a large pool of standing water. This must be it. At the far edge of the site is a JCB digger-type thing with tank tracks next to a big hole. It looks as though the blokes with yellow hats are planning to cover the water with the big pile of dirt. Then it dawns on me that this is the Area 51 of London rivers. They were finally trying to eradicate all trace of the famous Hackney Brook. Why? And who are they?

I quickly make a sketch of the scene on a Post-it Note, then retreat. One of the yellow hats spots me and mutters into a walkie talkie to one of his mates about five yards away, who is fidgeting with his ball of string. I quickly cross the road, staring into my A to Z, and pass a severe old grey brick Victorian house, the sort I imagine Charles Dickens had in mind when he described Arthur Clennam’s mother’s house in Little Dorrit: ‘An old brick house, so dingy as to be all but black, standing by itself within a gateway. Before it a square court-yard where a shrub or two and a patch of grass were as rank (which is saying much) as the iron railings enclosing them were rusty … weather-stained, smoke-blackened, and overgrown with weeds.’

And into a big estate. I keep looking behind me to check the men with yellow hats aren’t following. Who are the yellow hats, anyway? Historically, the yellow hat has denoted royalty – crowns and stuff (or religious folk with yellow auras/halos). Geoffrey Plantagenet, father of Henry II and precursor of the Plantagenet dynasty, was so-called because he wore a sprig of yellow broom (a Druid’s sacred plant) in his hat so his soldiers would recognize him. His daughter-in-law, Eleanor of Aquitaine, is credited with the creation of the Knights Templar, forerunners of the Freemasons. Whereas I watch a lot of Bob the Builder with my daughter – the show is about a bloke with a yellow hat who talks to machines and a scarecrow that comes alive.

A quick detour around the modern Iseldon (original name for Islington) village with its strange dips in the road as it goes down the river valley, and where the two heads of Hackney Brook would have converged, and then I head onto Hornsey Road, alongside the Saxon-sounding Swaneson House estate with its dank sixties/seventies shopping arcade with laundrette, grocers and chemists. When I was a kid I used to have books which showed what the new exciting world would look like, and most of the pictures were like the shopping arcade of the Swaneson Estate. What a crazily drab world must it have been in the sixties, with its Beatles harmonies, cups of tea and cakes, that we were suckered into thinking these shopping centres were the height of futuristic sophisticated living? To the left are some tired swings, then further up some beaten-up cars. Some local creative has recently taken a crowbar to one, leaving it like a smashed flower, powdery glass on the road, bits of ripped metal folding outwards. There’s a large pool of unhealthy-looking standing water, then another car, this time with no wheels. I have walked onto a set from The Sweeney, perfect for handbrake turns, jumping on and off bonnets, pointing a lot and calling people ‘slags’. It’s not so easy to find these bits of bombsitesque London now, even compared with five or six years ago. English Heritage should get areas like this listed.

Further up is a seventies-style Vauxhall estate car written over with some classic full colour graffiti. It should be in a gallery. But as a Time Out journo might say, (Mockney voiceover) ‘London is, in a very real sense, its own gallery.’

At the edge of the dirt track, near the road, is a sign for the estate managers who own the site – ‘state’ has been cut out of the sign, probably by some bright spark anarchist. Smash the state, please fuck the system NOW. That’s what Crass wanted, back on Bullshit Detector.

The living that is owed to me I’m never going to get,

They’ve buggered this old world up, up to their necks in debt.

They’d give you a lobotomy for something you ain’t done,

They’ll make you an epitome of everything that’s wrong.

Do they owe us a living?

Of course they do,

Of course they do.

Do they owe us a living?

Of course they do,

Of course they do.

Do they owe us a living?

OF COURSE THEY FUCKING DO.3

‘Do they owe us a living?’, Crass

Back on Hornsey Road I walk through the tunnel under the mainline railway to the north. The walls have the peeling skin of a decade and a half of pop posters. At the edges I can make out flaking scraps from years ago – Hardcore Uproar and Seal plus multiple layers of old graffiti.4

I’ve wandered away from the course of the river. Access is impossible due to the railway lines and the Ashburton Grove light industrial estate, the planned site of Arsenal’s new stadium. There’s a seventies factory development, a taxi car park and another broken car, this one burnt out as well. A big-boned bloke in a shell suit is inspecting it. Was it his? Maybe he was on a stag night and his mates did up his motor for a laugh. The road is a dead end so I walk back and around Drayton Park station with the river valley off to my left under the Ashburton Grove forklift centre – for all your forklift needs. There’s a beautiful big sky that’ll be lost when Arsenal build their new dream stadium. To the right is Highbury Hill, with allotments on the other side of the road banking down to the railway like vineyards, a vision of a different London.

And so into the reclaimed urban landscape of Gillespie Park. It’s an ecology centre developed on old ground near the railway, with different landscape areas and an organic café. I sit down for a while and stare out at the little stone circle and neat marshland pools, surrounded by grassland and meadow in a little urban forest created by local people, and listen to the sounds of thirteen year olds being taught about ‘nature’ by their teacher.

‘Can we catch some tadpoles sir. Goo on.’

‘No, now we’re going to look at the water meadow.’

‘Aww fuckin’ boring.’

The kid sticks his net into the pool anyway and swishes it around, while shouting, ‘Come on, you little bastards.’ The teacher, evidently of the ‘smile benignly and hope the little fucker will go away’ school of discipline, smiles benignly and begins telling the group about the importance of medicinal herbs.

I walk up the track past the ‘wetlands’ and can see Isledon village on the other side of the tracks. You get a sense of how the railway carved through the landscape in the mid-nineteenth century. Even then, when progress was a religion, people would have been aware of the landscape that would be lost:

I am glad there is a sketch of it before the threatened railway comes, which is to cut through Wells’ Row into the garden of Mr I. and go to Hackney. We are all very much amazed at the thought of it, but I fear there is little doubt it will come in that direction.

local girl Elisabeth Hole to her friend Miss Nicols,December 1840

In Gillespie Park it’s hard to discern the real contours of the land because it’s obviously been built up. There’s a little tunnel into the trees, then down a dirt track to a wooden walkway and to the left is marshland. It’s like a riverside. I stop and look across to the little meadow with another stone circle on the left. The rain lets up for a while and I sit down at a bench behind the stone circle with my notebook. Nearby, in the circle itself, sit four dishevelled figures. Two black guys, one old and rasta-ish with a high-pitched Jamaican accent, one young with a little woolly hat and nervy and loud, a tough-looking middle-aged cockney ex-soldier type and a rock-chick blonde in her late forties with leather jacket and strange heavy, jerky make-up. They look battered and hurt and are all talking very loudly, the men trying to get the attention of and impress the woman, as a spliff is passed around and they sip from cans of Tennent’s Super. They must be twenty-first century druids. The younger bloke, whose name is Michael, starts to shout out, ‘Poetry is lovely! Poetry is beautiful! Chelsea will win the league.’ I finish my quick notes and get up to go, as he smiles at me still singing the joys of football and poetry.

‘You’re right about the poetry anyway,’ I say.

‘Do you know any poems?’ he asks. I recite the Spike Milligan one about the water cycle:

There are holes in the sky where the rain gets inThey are ever so small, that’s why rain is thin.

‘Spike is a genius. What a man!’ he yells. ‘We love Spike, Spike understands us!’ and he starts to sing some strange song that I’ve never heard before. Maybe it was the theme tune to the Q series. Then the little Jamaican bloke with a high-pitched singsong accent jabs me in the chest, his sad but friendly eyes open wide, and he smiles.

‘If ya fell off de earth which way would ya fall?’

‘Er, sideways,’ I say, trying to be clever, because it is obviously a trick question.

‘NO ya silly fella. Ya’d fall up. And once ya in space dere is only one way to go anyway and dat’s up. Dere’s only up.’

‘The only way is up!’ sings Michael. ‘Baby, you and meeeeee eeeee.’

‘Whatever happened to her?’ asks the woman.

‘Whatever happened to who?’

‘To Yazz … ’

At this strange turn in the conversation I wave goodbye and walk towards the trees. The little gathering is a bit too similar to the blatherings of my own circle of friends, confirming my suspicion that many of us are only a broken heart and a crate of strong cider away from this kind of life. I can see Arsenal stadium up to the right, looming over the houses. At a little arched entrance, a green door to the secret garden, I come out onto Gillespie Road.

This is the heart of Arsenal territory, where every fortnight in winter a red and white fat-bloke tsunami gathers momentum along Gillespie Road, replica-shirted waddlers dragged into its irrepressible wake from chip shop doorways and pub lounges, as it heads west towards Highbury Stadium. As an organism it is magnificent in its tracksuit-bottomed lard power, each individual walking slowly and thoughtfully in the footsteps of eight decades of Arsenal supporters. Back in the days of silent film, when the Gunners first parachuted into this no-man’s-land vale between Highbury and Finsbury Park from their true home in Woolwich, south London, football fans lived a black-and-white existence and moved from place to place at an astonishing 20 m.p.h., while waving rattles and wearing thick cardboard suits in all weathers. No wonder they were thin. Going to a game was a high-quality cardiovascular workout.

(Then: Come on Arsenal. Play up. Give them what for (hits small child on head with rattle) spiffing lumme stone the crows lord a mercy and God save the King.

Now: Fack in’ kant barrstudd get airt uv itt you wankahh youuurr shiiiitttttt!!)

The source of this vast flow of heavily cholesteroled humanity is the pubs of Blackstock Road – the Arsenal Tavern, the Gunners, the Woodbine, the Bank of Friendship and the Kings Head. Further north are the Blackstock Arms and the Twelve Pins. To the south, the Highbury Barn. The pubs swell with bullfrog stomachs and bladders as lager is swilled in industrial-sized portions.

Walk from the south and there’s a different perspective. People in chinos with City accents jump out of sports cars parked in side streets, couples and larger groups sit in the Italian restaurants of Highbury Park chewing on squid and culture and tactical ideas gleaned from the broadsheets and Serie A. As I mentioned before, the scut line is around my street. Here, outside the Arsenal Fish Bar, which is actually a post-modern twenty-first-century Chinese takeaway, lard-bellied skinheads stuff trays of chips down their throats to soak up the beer. Inside the café, on the walls nearest the counter, there’s a picture of ex-Gunners superstar Nigel Winterburn looking like he’s in a police photo and has been arrested for stealing an unco-ordinated outfit from C&A, which he is wearing (should have destroyed the evidence, Nige).

In the Arsenal museum they have lots of great cut-out figures of many of the players who have long since departed. And a film, with Bob Wilson’s head popping up at the most inopportune moments. He does the voiceover but materializes (bad) magically every time there’s something profound to say, then dematerializes (good) in the style of the Star Trek transporter. Lots of nice old photos, and they make no bones about the fact that they never actually officially won promotion to the top division – in fact they’re even quite proud of the shenanigans and arm twisting that went on. My main question, how Gillespie Road tube was changed to Arsenal, is never answered apart from the comment that the London Electric Railway Company did it after being ‘persuaded’ (tour guide laughs) by Chapman.

It’s my belief that Arsenal were somehow involved in the shooting of Archduke Franz Ferdinand6 and the onset of World War I so they wouldn’t have to spend too long in Division Two. For lo and behold, the first season after the war they got promoted, despite only finishing fifth in the Second Division. How did that happen? It was decided by the powers that be (Royalty, Government, Masons, Arsenal) to expand the First Division following the end of World War I in an attempt to stave off proletarian revolution by giving them more football. By coincidence, Tottenham finished in the bottom three of Division One that year, yet were still relegated.

I dive into the Arsenal Tavern on Blackstock Road for a quick pint of Guinness because it’s only £1.60 during the day and I weigh up whether to ask the landlady about history but she is slumbering near the side door, arms like hams, chins on gargantuan bosoms, so I sit at the bar and chat to a gentleman called Dublin Peter, Cork Johnny, actually no I think it was Mullingar Mick, who anyway I’ve seen and talked to in here before and I notice that everyone is facing east. There are about twelve people in the pub – stare at pint sip stare at pint stare at wall stare at pint sip stare at pint stare at wall and repeat until need piss. The pub was called the New Sluice in the nineteenth century and I imagine they must have documents and photos of the pub back then.

The back room of the Arsenal Tavern is the exact point at which the boarded river crossed over Hackney Brook. I stand there for a few moments drinking and breathing hard, waiting for inspiration or some kind of sign. Peter Johnny Mick then appears again and starts explaining to me why Niall Quinn is still so effective as a front man for Sunderland: ‘He’s got mobility. Mobility, I tell you. He has the mobility of a smaller man. Have you seen how he can turn in the box?’

I walk along an alleyway past a building site where the crushed remains of a tower block lie in mesh-covered cubes like Rice Krispie honey cakes. Nearby is a weeping willow, a nice riverside touch. I eventually come out at the not very aptly named Green Lanes then cross through the northern end of Clissold Park about 200 yards from the New River walk, by the ponds – the brook ran alongside them. It’s an enchanted place, with birds and mad people sitting on the benches. For a brief moment, I imagine I am back a couple of hundred years. Through the gate and over Queen Elizabeth’s Walk.7 Then along Grazebrook Road, where sheep, I suppose, used to, er, graze next to the brook. Then the land rises up to the right. And left. There’s a school in the way so I go up to Church Street, which is full of young well-spoken mums, old leathery Irishmen dodging into the dark haven of the Auld Shillelagh, unshaven blokes in hooded tops sitting on the pavement asking for spare change, estate agents crammed with upwardly mobile families fecund with dosh or young couples looking longingly at places they can’t afford, skinny blokes with beards on bikes, kids, lots of kids, kids in prams, kids running, kids in backpacks, kids with ice creams, kids playing football, kids coming out of every doorway, Jewish guys with seventeenth-century Lithuanian suits, young lads with thick specs and thin ringlets, the odd big African in traditional dress, tired-eyed socialists and anarchists drinking in big, dirty old pubs and still dreaming of the revolution.

Turning into Abney Park Cemetery, I walk in a loop around its perimeter, past the grave of Salvation Army founder William Booth. It’s quiet and boggy, with lots of standing water and a strange atmosphere like a temperature shift or pressure change. Or something else … ghostly legions of Salvation Army brass bands emitting the spittle from their instruments. Branches curling down over old weathered stone, graves half buried in turf and moss, some with fresh flowers, which is strange as these graves are all well over 100 years old. I wade through big puddles as the track pretty much follows the course of the brook along the cemetery’s northern boundary. My beautiful new trainers keep slipping into the water and I fear I’ll be pulled down to an underworld by the grasping corpse-hands of the shaven-headed vegan N16 dead. The track ends at the main entrance on Stoke Newington High Street.

Just down the road is the Pub Formerly Known As Three Crowns, so called because James I (and VI) apparently stopped for a pint there when he first entered London and united the thrones of England, Scotland and Wales for the first time. Maybe he had the small town boy’s mentality and thought that Stoke Newington was London (‘Och, ut’s on’y gorrt threee pubs!’) In those days Stokey was pretty much the edge of London. Up until that time the Three Crowns had been called the Cock and Harp, a grand fifteenth-century pub which was knocked down in the mid-nineteenth century just to be replaced by a bland Victorian version. When I first used to come to N16 the three nations had become Ireland, the West Indies and Hardcore Cockney, and the age limit was sixty-five and over. Then it was the Samuel Beckett (Beckett wasn’t from bloody Stoke Newington). Now it’s called Bar Lorca (and neither did bloody Lorca. Bloody). How unutterably sad is that? (Puts on cardigan and lights pipe then walks off in a huff). There should be. A law against. That kind. Of. Thing.

I continue towards Hackney, with the common on the right. This used to be called Cockhanger Green, suggesting that Stoke Newington was a sort of Middle Ages brothel Centre Parcs, until someone, most likely a Victorian do-gooder, decided to change the name to the rather less exciting Stoke Newington Common. There used to be an exhibit timeline at the Museum of London showing a Neolithic dinner party. A nineteenth-century archaeological dig had unearthed evidence of London’s earliest Stone Age settlers right here next to the Hackney Brook. The exhibit showed what looked like some naked hippies in a clearing holding twigs, and barbecuing some meat. These days they’d be chased off by a council employee or more likely a drug dealer. I buy a sandwich and wander onto the common then sit down to finish my snack, wondering if any evidence of my meal will appear in some museum 3,000 years hence (‘And here we have artefacts from the time of the Chicken People … ’).

At the junction with Rectory Road ‘Christ is risen’ graffiti is on a wall. A gang hangs about on the street corner, just down from Good Time Ice Cream, typical of gangs around here in that they are all around eleven years old.

A tall black geezer strolls up to me and cocks his head to one side.

‘Aabadadddop?’

‘What?’

‘Aabbadabbadop?’

‘What did you say?’

‘Are you an undercover cop?’

‘Argh?’

‘An undercover cop, man? Talkin’ into that tape recorder. What you doin’?’

I spend about five minutes explaining to him about the buried rivers, in my special ‘interesting’ researcher voice, showing him the Hackney Brook drawn into my A to Z and how the settlements grew up around the stream. His eyes start to glaze over and he makes his excuses and speeds off towards Stoke Newington.

At Hackney Downs I can see the slope of the shallow river valley with an impressive line of trees, like an old elm avenue, except they can’t be elms because they’re all dead. At this point I should say what kind of trees they are, being a country boy, but fuck me if I can remember. I used to be able to tell in autumn by looking at the seeds.

At the Hackney Archive there are some old illustrations of Hackney in which the river looks very pretty and rustic as it winds its way past various countryish scenes and one of the Hackney Downs in the late eighteenth century, with a little Lord Fauntleroy type looking down into a babbling (or in Hackney these days it would be ‘chattering’) crystal stream. Behind him, where now there would be muggers, dead TVs, piss-stained tower blocks and junkyards, are bushes, shrubs, trees and general countryside.

Benjamin Clarke, writing 120 years ago, lamented how much it had changed in the previous 150 years and had it on good authority that in the 1740s ‘the stream [“purling and crystal”] was quite open to view, trickled sweetly and full clearly across the road in dry weather but rapidly changed to a deep and furious torrent when storms along the western heights of Highgate and Hampstead poured down their flood waters’.

A few people are hanging out in the Downs but it’s not a real beauty spot, more an old common. A battered train clatters past along the embankment to the right. Along cobbled Andre Street and its railway arches with garages, taxis, banging, welding, industrial city smell of petrol and chemicals, and those urban standing-blokes who never seem to have anything to do. And, of course, smashed cars and engine parts. People doing business, chatting, negotiating, and almost medieval noise among the cobbles. Are you into cars? If not what are you doing down here? We all love cars. Water drips along the cobbles. One day all this will be really shite coffee bars. I make it to the end of the street without buying a car then turn left past the Pembury Tavern – alas, not open any more.

Here, the Victorian stuff blends with spoiled tower blocks/failed high-density housing projects, burned-out cars piled high behind wire fences; swirling purple, shaved-head speccy blokes jogging with three-wheeler prams; shaven-headed bomber-jacketed blokes pulled along by two or three heavily muscled dogs, nineteenth-century schools refurbished for urban pioneers with lots of capital. Hackney used to be shitty, now it’s not so shitty (Tourist sign: ‘Welcome to “Not As Shitty As It Used To Be” Country!’) The brook in central Hackney was culverted in 1859–60. In his book, Benjamin Clarke visits the old church and finds a ducking stool in the tower which used to be near here and where they’d give scolds (women with opinions) the dip treatment. A bloke is following me laughing madly and loudly, then runs across the road into Doreen’s pet shop, no doubt to buy a budgerigar for his lunch.

I head up towards Tesco, built on the site of old watercress beds – I reckon the stream goes right underneath their booze section. I hang around near the liqueurs for a while, checking the emergency exit, when the alarm goes off so I nip around the vegetable section and out by another door. Onto Morning Lane now, which follows the line of the river. There used to be a mill for silk works here and the Woolpack Brewery using Hackney Brook water. I love Benjamin Clarke’s idea that this is a River of Beer. I wonder how easy it would be to turn a stream into beer. Just add massive amounts of hops, malt, barley and yeast, I suppose. Further down there used to be a Prussian blue factory. Lots of big blond lads with moustaches singin’ ‘bout how their woman gone left them ja and ’cos the trains are so damn efficient she’ll be miles away by now. Woke up this morning etc., etc.’ Oh, blue factory, that’s ink, right? Now it’s heavy traffic, cars, white vans, trucks, housing estates.

Large swathes of this part of Hackney must have been flattened by bombs in the Second World War. Or by the progressive council madmen who hated the elitism of nice houses and squares. Past Wells Street and little funky shops where the tributary marked ‘Hackney Brook’ on my map used to flow. Reggae blasts out from a shop – Rivers of Dub. People shouting, radios blaring, big arguments. At the end of Wick Road two guys in tracksuit trousers (or sports slacks) are giving hell to each other and pointing at each other’s chests. Up above is the sleek black hornet shape of a helicopter, watching. On the other side of these flats, to the north, are the Hackney marshes.

Two pubs here, one a cute compact place, dark green and yellow Prince Edward, not the not-gay TV production guy but the Prince of Wales who became Edward VII, the fat bloke with a goatee who liked shagging actresses. I have an idea for stickers with a river logo and pint glass plus a thumbs up sign, like an Egon Ronay guide thing, that landlords of pubs along the routes of rivers could put on their front doors.

Benjamin Clarke wrote that when he was young that ‘the popular name for the area around Wick Lane and beyond was “Bay” or “Botany”, so nicknamed because of the many questionable characters that sought asylum in the wick, and were ofttimes not only candidates for, but eventually contrived to secure transportation to Botany Bay itself’.

More flats here, cubist and Cubitt mixed together. Then at the junction to Brook Road the roads rise up each side from the river valley. I keep straight on. There’s a new Peabody Trust building site, announced by their little logo, which is two blue squiggly lines, like waves – maybe they only build on top of buried rivers. From Victoria Park, on a slight hill where the river once skirted round the north-east corner, I can see tower blocks in the distance of different shapes and sizes.

Back out and down into the river valley into the heart of the Wick under some rough-looking dual carriageways, past a lime green lap dancers’ pub on the left. I turn right underneath both roads of the A12 Eastcross route, onto the Eastway. A little old building says ‘Independent Order of Mechanics lodge no. 21, 1976’. Their sign is a sort of Masonic eye with lines coming out from the centre. I pass the Victoria, an old Whitbread pub seemingly left high and dry by the road building, and St Augustine’s Catholic Church, which hosts Eastway Karate Club. Then a beautiful thirties swimming pool in the urban Brit Aztec style. I look along Hackney Cut, a waterway made for the mills of the district so the Lea could still be navigable, as it stretched down further into the East End.

Now I am in Wick Village with its CCTV and sheltered housing. It’s pretty dead, like the end of the line, a real backwater – dead cars resting on piles of tyres then a graveyard with hundreds of cars piled up. I climb up a footbridge to take a look around. It’s still ugly from there, except I can see more of it. Lots of dirt in the air, windswept, everything is coated in it, blasted and bleached, grit in my eyes. Someone has dropped a big TV from a height and it lies in pieces by the stairs – perhaps in protest at the death of the Nine O’clock News. Great piles of skips here like children’s toys, and lots of traffic. I cross over the Stratford Union Canal lock and to the Courage Brewery, where an army of John Smiths bitter kegs wait to do their duty.

A couple of old people dawdle up to me and I ask them about what they know about Hackney Brook.

Responses of local old people when you ask them about an underground river

1. Outright lying

2. Wants to unburden soul

3. Does rubbing thing with ear suggesting they’re contacting some secret organization

4. Doesn’t understand me

5. Idea of underground river makes them want to urinate – ‘You are my best friend!’ etc.

There’s a plaque for the Bow Heritage Trail and the London Outfall Sewer walk. Part of London’s main drainage system constructed in the mid-nineteenth century by Sir Joseph Bazalgette. I can smell the shit. It’s a shitty sky as well. But at last I can hear birdsong. There are scrub trees, wildflowers, grasshoppers, daisies and cans of strong cider.

Finally I am at the point where the newer Lea Navigation cut meets the old River Lea/Lee. The name is of Celtic origin, from lug, meaning ‘bright or light’. Or dedicated to the god Lugh (Lugus). There are two locks here. This is the end of my walk, although the path continues to Stratford marsh. Two big pipes appear, on their way down to a shit filter centre (technical term) somewhere out east. Maybe there is poo in one and wee in the other. I go down some steps to have a closer look at the river. The sewer is in a big metal culvert under the path. There’s a small sluice gate on the other side, also an old wooden dock. Water rushes out a bit further up, and I’m happy. Maybe that is the Hackney Brook, maybe it isn’t. It’s good enough for me.

To the left is Ford Lock near Daltons peanut factory, on the right the placid winding waters of the old Lea. I cross over the locks and am blasted by the smell of roast potato and cabbage. It’s deserted, like an old film set.

My online dream doctor Mike’s online dream interpretation arrives:

Hello Tim!

A very interesting dream indeed! It looks to me more like it is set in a future setting than in the past, and it sounds like a very beautiful place! (!) Water is symbolic of change, and it seems that your dream makes quite an artwork out of change. Walking over the deep crevices in the ground is symbolic of passing over problems in life successfully. If you were not passing over them successfully you’ll be falling into or stumbling on the crevices. The glass over it covered in little red dots sounds to be very symbolic of health issues.

The flying water sounds to be very symbolic of the turbulent future, but the way you handle yourself and your feelings about this dream make it sound like everything will be fine. It sounds like this dream is predicting some hard times ahead, but you are able to overcome them and continue along a path.

I certainly hope this helped you, there really wasn’t a whole lot to go on. If I may be of further assistance please feel free to write.

Sincerely,

Mike

ps: This is not to be considered medical or psychological advice because I am not a doctor or psychologist. I offer this as my opinion and should be evaluated with this in mind.

I phoned up Arsenal F.C. and got through to the club historian, who denied any knowledge of the underground river (he would) but he did tell me that the site was purchased from the St John Ecclesiastical college. The Knights of St John, the Knights Hospitallers, acquired the Templars’ land when they were outlawed in the early fourteenth-century. Canonbury Tower, whose lands stretched down to St John’s Priory, Clerkenwell, has Templarism for its foundations, and a cell in Hertfordshire, on or near, the old estate of Robert de Gorham, was connected with the Order of St John established in Islington. All of Hackney was owned by the Templars, and large parts of Islington. Does this mean anything? Is Highbury Stadium a Masonic stronghold?

The historian skilfully rebuffed my information-gathering technique which, I’ll be honest, consisted of me saying, ‘Blah blah underground rivers blah – so, are you a Mason?’ in a Jeremy Paxman voice. He laughed and made a joke of it. Then I heard a very audible click, which could have been the gun he was about to shoot himself with. Or the sound of secret service bugging equipment. MI5 could be listening in. Or is it my hurdling knee playing up again?

Various people have attempted to explain Occam’s Razor to me. Basically, if there are two explanations for something, you should choose the simplest.

Choice 1: The land near reclaimed rivers was cheap and was bought up by football clubs.

Choice 2: Something to do with mysticism and Masonry, paganism, choosing a river site and picking up on power vibe of ancient druids for occult football purposes.

Hmm. A lesser-known theory is Occam’s Shaving Brush, in which you coat everything with a thin veneer of absurdity and then you can’t see the chin for the stubble. As it were. By burying the streams they – the Victorian sewer maker, brick manufacturers, builders, football club chairmen, the Masons, Edward VII – were burying the last vestiges of the scared goddess worshipping holy springs. It was violent and anti-female, defiling London. No, I meant sacred goddess.

‘What have you got to say to that then?’ I asked the Arsenal historian.

He’d hung up.

More religious people are starting to turn up at my door. It’s the end times, they say. They are joined by an ever-growing band of needy folk who just want something. Yugoslavian immigrants who can only say ‘Yugoslavia’ and ‘hungry’, Childline charity workers, Woodland Trust, gas board people wanting to sell us electricity, electricity board people wanting to sell us gas, people from Virgin wanting to sell us electricity, gas, financial services and some of the thousands of copies of Tubular Bells by Mike Oldfield that they’ve still got piled up in an underground warehouse in the sticks, homeless people trying to sell us kitchen cleaning gear, cancer charity people, environmental groups. One day I opened the door and there was a chicken on the floor outside. It must be an omen. Actually it was a half-eaten piece of KFC with a few chips left behind as well. An urban trash culture post-modern voodoo juju hex. Without a doubt.

Film idea – The Herbert Chapman Story

It’s a mixture of Foucault’s Pendulum, Escape to Victory and The Third Man. Takes over struggling Arsenal and gets in with the Masons to utilize the power of Hackney Brook. Have a spring. Players drink magical waters.