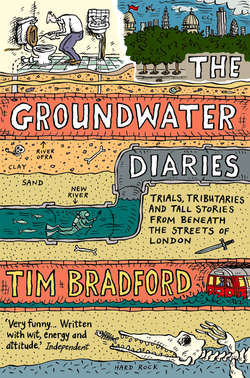

Читать книгу The Groundwater Diaries: Trials, Tributaries and Tall Stories from Beneath the Streets of London - Tim Bradford - Страница 6

1. A Bloody Big River Runs Through It

Оглавление• London’s forgotten rivers

Dream of a big river – river obsession – Danish punk explosion – Samuel Johnson – London – electric windows – pissed-up Jamaican grandads – Hemingway – burning Edward Woodward – global warming – the underground rivers – old maps – lots of rain – roads flooded – blokes digging up the road

I have a recurring dream. I’m standing in the shallows of a silver-grey mile-wide river. My wife, in a blue forties-style polka-dot swimsuit, is next to me, with our daughter. We are picking bits of granary bread out of the river and putting them into black bin liners. On the shore stands a big wooden colonial-style house. I first had the dream before my daughter was conceived, in fact long before my wife and I even got together. Dream analysts might say I was crazy. But they are the crazy ones, thinking that punters will be fooled by fancy titles like ‘Dream Analyst’. I contacted a dream analyst, anyway, because I can’t help myself. It was one of those Internet ones with swirly New Ageish graphics which denote a certain amateur-cosmic badge of quality. You had to type in your dream, then your credit card details. I’m no mug, so I chose one that only cost sixty dollars. A few days later my dream analyst (whose name was Keith – I had expected something a little more along the lines of Lord Sun Ra Om Le Duke de Dream Chaos Universale) sent me an email.

It is a pleasant dream showing you the very positive feelings of the family. You are together, safe, gathering and storing food. We survive best in a family and ‘tribe’, and this very primitive dream stimulus prompts you to make the most of that. You are lucky, most of the dreams like this work the other way by having the unit threatened. You might see your daughter drowning, thus frightening you (the objective of the dream) into increased protection in life.

I like it! A good dream. You even had it before the event, stirring you on to make the union and reproduce the species.

But I wasn’t totally satisfied. Why did my wife’s swimsuit have polka dots? Did the bread have something to do with religion? From my description, would he say the wooden house was designed in an Arts-and-Crafts style? And why were we in a river? Dream Analyst had gone quiet. Except for a ghostly hand that reached out from my computer terminal with a note that said ‘60 dollars please’.

OK, I am obsessed with rivers. Especially dark ones, like the River Trent in the East Midlands, 20 miles from where I grew up. It’s deep and unfathomable. Like time, but with fish and old bikes at the bottom. My mum used to tell me a story about a local man whose daughter fell from a boat into the river. He jumped in and saved her, but was carried off by the tide. Is his body still there, in the river? Maybe. So how deep is it, then? Very deep, my parents would say, shaking their heads and sucking in their breath. Fantastic. I’d lie in bed thinking abut the river and what it must be like to drown. I couldn’t imagine the bottom. It was like visualizing a million people or the edge of the universe.

I remember everything in the town where I grew up being smaller than elsewhere in the world (the cars, the voices, the people) and this was especially true of our ‘river’, the Rase. At its highest near the mill pond, the Rase could be up to 2 feet deep, but it usually flowed at a more ankle-soaking 8 to 12 inches. In early 1981, the placid river burst its banks and many people, my aunt included, were flooded out of their homes (ironically, my new copy of Lubricate Your Living Room by the Fire Engines floated off past her sofa). A couple of months later my friend Plendy and I decided to try and placate the Rase by making a pagan sacrifice. It was important to give something that we both treasured, but in the end were too stingy and instead nailed down a copy of Bullshit Detector (an anarcho-punk compilation album I’d bought some months earlier) to a wooden board, placed it in the water and watched it head off downstream. We liked to think it eventually found its way to the North Sea then travelled the world, spreading its gospel of three-chord mayhem and anarchist politics.

The men with the powerHave pretty flowersThe men with the gunsHave robotic sons.

‘The Men with the Guns’

At the very least, most Scandinavian punk music must be down to us.

Scene 1: A farm in Denmark. A big-boned farmer finds a record nailed to a board on the shore near his house. He removes it then puts it on a record player. It’s good. He starts pogoing.

Scene 2: A few days later, in the farmer’s barn, a punk band is practising. The farmer is on lead vocals.

Scene 3: A tractor lies half-buried beneath long grass. There are cobwebs on the steering wheel.

Scene 4: A painting of the farmer and his wife in the style of Gainsborough’s Mr and Mrs Andrews. The farmer has a mohican. The wife looks very, very angry.

Long before we were offering third-class punk records to the water spirits, rivers were worshipped as gods. Those red-haired party animals, the Celts, threw things they most valued – shields, swords, jewellery, and other anarcho-Celtpunk memorabilia – into them (a residue of this is our need to chuck loose change and crap jewellery into fountains). To different cultures across the globe, rivers have represented time, eternity, life and death. It is believed that our names for rivers are the oldest words in the language, some predating even the Celts. Many major settlements were located at healing springs sacred to the pre-Roman goddesses, and many rivers, such as the Danube, Boyne and Ganges, were named after goddesses. The Thames is one of these, its name apparently deriving from a pre-Indo-European tongue and referring to the Goddess Isis. Some posh Oxbridge rowing types still call it that. Well, we’ve got names for posh Oxbridge rowing types. Like ‘big-toothed aristo wanker’, etc.

London is beautiful. Samuel Johnson, in the only quote of his anyone can really remember, said, ‘When a man is tired of London, he is tired of life.’ He may have been a fat mad-as-a-hatter manic depressive in a wig, but there is something in his thesis. London’s got its fair share of nice parks and museums, but I love its underbelly, in fact its belly in general – the girls in their first strappy dresses of the summer, the smell of chips, the liquid orange skies of early evening, high-rise glass office palaces, the lost-looking old men still eating at their regular caffs even after they’ve been turned into Le Café Trendy or Cyber Bacon, the old shop fronts, the rotting pubs, the cacophony of peeling and damp Victorian residential streets, neoclassical shopping centres, buses that never arrive on time, incessant white noise fizz of gossip, little shops, big shops, late-night kebab shops with slowly turning cylinders of khaki fat and gristle in the window, the bitter caramel of car exhaust fumes, drivers spitting abuse at each other through the safety of tinted electric windows, hot and tightly packed tubes in summer, the roar of the crowd from Highbury or White Hart Lane, dog shit on the pavements, psychopathic drunken hard men who sit outside at North London pub tables. London has got inside me. I’ve tried to leave. But I always come back. It’s love, y’see.

As you can probably tell, I’m a sentimental country boy. No real self-respecting Londoner would love their city the way I do (and before you ask, Dr J. was from the Black Country).

My love affair started early. The first trip was in the late sixties. We went to the Tower of London and some museums while the streets were ‘aflame’ with the lame English version of the ‘68 riots (‘What do we want? Cheap cigarettes and decent central heating! When do we want it? How about Wednesday? I’m visiting my Auntie for a long weekend!’). Years later I visited an old college mate in a little flat in Finsbury Park. I slept on the floor and spent three days sitting in pubs where we were the only people without overgrown moustaches and some obscure connection to the Brinks Matt robbery. A drunken fat bloke with a moustache the size of Rutland showed me how to drink Guinness properly. Throughout these years it seemed that London was a place full of record shops, shouty Irish blokes, pissed-up Jamaican grandads and stoners. I’ve found it hard to shake off these early impressions.

In January 1988 I hit cold evening air at Highgate tube, north London, a heavy-duty iron forties typewriter (a prerequisite for the aspiring writer) strapped to my body with a mustard and maroon dressing-gown cord, guitar on my back, clutching a bag with a spare pair of jeans, a couple of T-shirts and a change of underwear.

I had arrived, like Hemingway in Paris, in a grand European capital where I would soon become a famous novelist and songwriter. OK, not like Hemingway at all. Unless his music has been kept quiet all these years.1 I had a simple plan. Within six months I’d have clinched a record deal and would be starting my second novel. I was here to scrape the gold off the London pavements and cart it back to Lincolnshire, to be held aloft in procession through the streets of my old home town, before sharing my booty with all and sundry in the market place.

And so twelve years on I’m still here. Pushing a pram around for an hour or so every day and watching too much kids’ TV.

I love London in late summer/early autumn. Hot weather. Then it’s cold. Then it’s cold-but-hot cold. Cold days have warm miasmic breezes. Hot days have brittle, icy winds that hide behind hedges and garden walls. Then it’ll piss down. The weather’s going crazy. You always start your books with stuff about weather, said one (pedantic) mate. What do you mean always? I’ve only written one. Yeah but you started that with weather and now you’re starting this the same way.

But weather is important. People on these islands have always been obsessed with it. The Celtic people worshipped the weather gods. The seasons. Agriculture. Sacrifice. Dancing naked around standing stones. Burning Edward Woodward in The Wicker Man. Listening to ambient techno while off their faces on magic mushrooms. The British Isles can have wind, sun, rain and snow all in one day. My mate agreed and pointed out that he lived here too so also knew these things. But now it’s changing more and more, What With Global Warming And That. The east of England could be underwater in a few decades. I want to write a book about Lincolnshire some day. But Lincolnshire may not be around for much longer.2 London too. The climate will get wetter rather than hot and dry. It could also get colder in winter if the Gulf Stream gets clobbered by cold water from the melting ice caps flowing into the North Atlantic, pushing the warmer water further south. More importantly, my book about Lincolnshire will then be about an area that no longer exists. Or one of those Undersea-Lost-World-type things.

‘How do you know all this stuff?’ asked my mate.

‘I saw it on TV.’

Anyway after all the hotcoldrainsnowsuncoldhot stuff, it went cold again. Maybe we had gone straight from early summer to late winter. It became so consistently grey that my sensitivity to the London seasons became even more numbed than usual. As a kid, in rural Lincolnshire, every day held new smells and sensations. Cow parsley. Corn. Peas. Sugar beet. Rotting leaves. The perfume of a girl who’d just chucked me. Singed hairs on the back of a fat farmer’s neck as he gets his ‘winter cut’ at the local barber shop. Rotting roadkill. Cow shit. Blood.

And after a few days of cold, the sun suddenly came out and I guessed, from stuff in the newspaper, it must be some time in August. On the way back I walked along the little avenue of trees in Clissold Park. This is a sacred space where we sometimes sit in the evenings, surrounded by people doing tai chi, yoga, reading, skinning up or snogging, and we watch some of the crap football lower down in the park. Fat women jog tortuously around the little running track. Above, breadcrumb clouds scud across a perfect sky, and a leather football hits a nearby tree.

For someone who finds rivers fascinating (‘Yes, would you like to see my gold-embossed collection of nineteenth-century etchings of the tributaries of the Tyne?’) underground rivers give me an extra thrill. As well as all that energy and … water … there’s the fact that you can’t see them. They’re erotic, mysterious and magical because they’re hidden and therefore may or may not really exist. In the early nineties when I lived near Ladbroke Grove I frequented a little second-hand bookstore at the northern stretch of Portobello Road run by a serious young Muslim with a goatee. His big gimmick was a job lot of poetry books by Reggie Kray, but my real find was a three-volume set called Wonderful London which he sold me for twenty quid. The volumes were published in 1926 – lots of pictures of London in the 1880s contrasted with the twenties with captions saying ‘Gosh chaps, look what a mess we’ve made of our city, eh what.’ If only they could have seen what was to come.

The books were brilliant – lots of highbrow columns, anecdotal journalism and chummy recollections, but by far the best was a chapter in Volume Two, ‘Some Lost Rivers of London’ by Alan Ivimey. He described in exquisitely bright purple prose the undulations to be experienced in Greater London – the geography and geology of the Thames Valley. London, said Alan, was an uneven plain, bordered north and south respectively by clay and chalk hills with a large river flowing through the middle of it, and in between the hills and the river were undulations of sand and gravel and clay. The once proud tributaries that flowed through this flood plain were now little more than ‘dirty drains beneath the bowels of the earth, trickling weakly along their old beds’.

There was a small map showing the main rivers that had disappeared around fourteen (though possibly more) including the Westbourne, the Tyebourne, Bridge Creek, Hammersmith Creek, the Wandle, the Effra, the Neckinger, Falcon Brook, the Holebourne (also known as the Fleet), the Walbrook and the New River. For hundreds of years people had been shitting and pissing and throwing their dead relatives into these rivers so that, by the start of the nineteenth century, most had become open sewers.

Travel back in time. Imagine I’ve a Public-Information-Broadcast-type voice:

(Swirly ethereal New Age synth music). Once upon a time London was full of vales with water meadows, woods and streams. Man first inhabited the area in Neolithic times, the Celts had a trading and fishing settlement near the Thames. Since then Romans, Saxons, Vikings and Normans invaded … blah blah Tudors and Stuarts … Georgians … lovely squares … Victorians – nice train stations … then Edwardians then wartime then the sixties, seventies … design nightmares … eighties … nineties … modern London, a teeming famed-piled post-modern high-tech metropolis where once was once rolling countryside.

I like to look at urban landscapes or, to be more specific, how urban landscapes would have looked before the industrial revolution. I can see the past, although it takes a lot of concentration. I walk down a street, look up at the old buildings then look down again at the winding lanes that once would have been filled with shit, rats and corpses. I’ve invented a special virtual reality gizmo that allows the user to input map co-ordinates then choose a year and the display will show the scene as it was then. So, for example, if I’m walking up Blackstock Road in Finsbury Park and I input 1760, it’d be a sandy lane leading from Stroud Green Farm to the heights of Highbury. A button would allow you to turn off all modern interference, such as cars or other people, but, of course, this would only be advisable in very safe conditions. Actually, by ‘invented’, I mean had an idea and talked to my wife about it. She smiled and asked, ‘Are the dreams still bad?’

After doing some research (half an hour on the Internet looking for ‘underground rivers’), I discovered that living above an underground river, or groundwater, is bad for your health and should be avoided. This is to do with radiation and ‘bad’ spirits – that’s why feng shui experts, hippies and mad country folk practise water divining. I’m always on the lookout for unified (and easy) theories of everything and it occurred to me that my insomnia, strange dreams and fragmented state of mind could be due to the fact that, since coming to London I had always lived above subterranean streams.

I got a surveyor to come round to investigate a little damp problem we had noticed and, as he was walking around with his damp detector, I tossed a casual question in his general direction:

‘Do you think the … er, damp … could be caused by … er … the lost underground rivers of London like the New River, Fleet, Westbourne, etc., ha ha, as it were?’

‘What a load of bullshit,’ said the surveyor. He moaned that people were always banging on about underground rivers. Were they? I said. I’m the only person I know who does – everyone else seems to be very bored with the whole concept already.

I live on a road with a watery name so thought that should be enough evidence, but decided to check out my theory on various old maps I’d picked up. Two Victorian maps showed the New River, which seemed to run along where our road is now. Then, during a visit to Stoke Newington library, I found an old leaflet about Clissold Park which showed that the raised avenue of trees was where the heavily banked river ran and continued past the brick shed at the park gate (actually an old pump house), then it went under Green Lanes and along our road before heading north. ‘My God,’ I thought to myself, slapping my forehead, ‘so the tai chi people, crap footballers, snoggers and dopeheads are perhaps in exorably drawn to the electro-magnetic currents of the river!’ I was so excited I got goose pimples and had to go for a shit immediately.

At the eastern end of my street, opposite Shampers Unisex Hair Salon (cut £3.50, blow dry £7.00), water is bubbling up through the cracks in the pavement in about six places. This little spring is clear and shiny in the morning sun and I want to reach down and drink from it, only it’s flowing over fag butts, withered banana skins, discarded ice cream wrappers and dog shit. It babbles and swirls for a few moments at the side of the road among a narrow band of cobbles, then pours along the kerb to a shallow trough in the road, where a pool is slowly forming. An empty can of Strongbow is already floating in it. As the water level in the pool increases, a group of middle-aged black people start to arrive at this end of the street. They are all impeccably dressed, the men in dark suits and blazers with ties, the women in dazzling summer dresses and hats. A tall man in specs issues instructions then they fan out, rapping fastidiously on doorsteps in twos, clutching their books and spreading the word.

‘Who is it?’

‘We want to talk to you about Paradise.’

‘Fuck off,’ says a bloke from an upstairs window.

‘The end of the world is coming.’

‘Who gives a fuck?’

It has been raining on and off for forty-eight hours, melancholy vertical summer holiday rain with an afterscent that’s like faint pipe tobacco mixed with petrol and oranges. Plump droplets hang from the trees. A quick sortie around the neighbourhood shows that many of the area’s drains are rebelling. In the network of streets to the north east of the Arsenal Tavern pub small lakes are forming in the roads. It’s as if the tarmac and concrete have been pushed down and the area is reverting to swampland.

By early evening, the pool of water stretches across to the other side of the road. It’s still flowing heavily from the same cracks and along underneath the iron railings. Half an hour later, four men are standing in the pool, one with a clipboard. They’re all looking down at the water.

‘Have you got a burst underground river, then?’ I ask, smiling. The man with the board looks at me nervously and smiles, but doesn’t say anything. As I walk down the road a mechanical drill starts opening up the pavement Er er er er er ererererererererererereerererere. Down below, the New River flows on, biding its time.

1 (Peter Skellern style number) Is it me Is it you We two Let’s do It.

2 Reader: Does Lincolnshire only exist so that you can write a book about it?