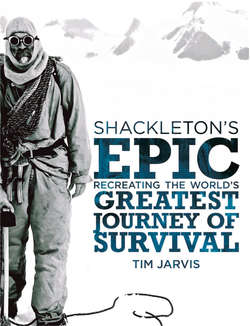

Читать книгу Shackleton’s Epic: Recreating the World’s Greatest Journey of Survival - Tim Jarvis - Страница 10

Оглавление4

IRON MEN

The team.

Courtesy of Paul Larsen

“Life is either a daring adventure, or nothing.”

Helen Keller

Testing our mettle: South Georgia’s challenges lay ahead of us.

Courtesy of Tim Jarvis

On the face of it, we were two teams attempting the same journey ninety-seven years apart. On closer inspection, there were many differences over and above the passage of time. I needed to recruit just five people willing to undertake a dangerous journey in a small boat across the world’s roughest ocean, followed by a climb across a mountainous island. Shackleton, on the other hand, sought twenty-seven men to fill a range of positions—everything from meteorologist, biologist, and physicist through to cook—for a journey of geographical and scientific discovery crossing the mighty continent by land, not sea. He had no idea when recruiting his team that he, together with five of his most able men, would be subjected to the ordeal of crossing the Southern Ocean in the James Caird. That he managed to pursue the goal of crossing the ocean in his small boat with the same rigor and determination as the original unachievable mission is just part of the Shackleton legend.

Shackleton received some 5,000 applications for the twenty-seven available places on his expedition. One of the most intriguing read:

Three strong healthy girls, and also gay and bright, and willing to undergo any hardships, that you yourself undergo. If our feminine garb is inconvenient, we should just love to don masculine attire. We have been reading all books and articles that have been written on dangerous expeditions by brave men to the Polar regions, and we do not see why men should have the glory, and women none, especially when there are women just as brave and capable as there are men.

No women went on Shackleton’s expedition. A desire for historical authenticity on the part of the Shackleton family meant I could take none either.

In organizing expedition logistics, I wore an impressive carbon furrow between Australia, the UK, and the US, raising funds and sounding out suitable candidates. These included leading outdoorsmen Martin Hartley and Paul Rose as well as British sailor Pete Goss and Australia’s Don McIntyre. My goal was a team split fifty-fifty between sailors and climbers. Additional skill sets—an ability to repair the boat or to film the experience—were also required. Applicants ranged from an eighty-year-old sailor, a thirteen-year-old girl, librarians, musicians, polar historians, and surgeons through to high-caliber sailors, climbers, and photographers. Fortunately, while expedition logistics and funding remained opaque, the perfect candidates revealed themselves to me at just the right time, normally in response to a specific need. Ed Wardle had come forward when many other cameramen’s names were being bandied about but none seemed an obvious choice. I met him at a London cafe in June 2012 and he arrived dramatically on a powerful motorbike dressed in leathers. Quite apart from the fact he was Raw TV’s choice, I could see immediately he was a solid guy, and I liked his efficient, can-do attitude and his polite, direct style. I could also see myself getting along with this Scot in the confines of a small boat and felt I could trust him. And because he had summited Everest twice, spent fifty days on his own in Alaska living off the land, and was a former UK free-diving champion (free divers hold their breath and go as deep as they can) he was an ideal candidate. The fact he had compromised personal hygiene standards and eaten absolutely anything while in Alaska was enough on its own to qualify him for life aboard the Alexandra Shackleton. And while I hoped we wouldn’t have to call upon his free-diving skills, at least if we sank someone might survive to tell the story. As soon as I let Ed know he was on the team, he repaid me by getting to work on the camera and power systems for the Alexandra Shackleton, figuring out how best to film at sea and while crossing South Georgia.

The other blindingly obvious choice for the team had come a month or two earlier via a combination of reputation and an introduction from Seb, via armed forces channels. Just as Shackleton had wanted and managed to include a Royal Marine in his expedition team (in the form of Thomas Orde-Lees), we wanted to include Baz Gray, a Royal Marine. His role as mountain leader chief instructor, however, meant he trained all other mountain leaders across the UK’s armed forces, had climbed everywhere, was a cold-weather expert for the Royal Navy’s Antarctic patrol ship HMS Endurance, and had already done the crossing of South Georgia in modern gear and awful weather. The fact that actor Hugh Jackman and Prince Andrew had trusted him with their lives during recent charity rappels (and both had survived) also instilled a certain sense of confidence. Baz had the driest sense of humor you could imagine and a burning desire to cross South Georgia the old way—something of a rite of passage for Royal Marines. I welcomed him onto the team and he immediately took responsibility for planning all aspects of the South Georgia crossing. The only downside was Baz’s predisposition to break into the opening lines of whatever song suited any given situation. But Shackleton would have loved it, I’m sure, as it seemed to tally with his sometimes unorthodox recruitment criteria. Reginald James said of his interview with Shackleton: “All that I can clearly remember of it is that I was asked if I had good teeth, if I suffered from varicose veins, and if I could sing.” The interview was over within five minutes and James was appointed the expedition’s magnetician and physicist.