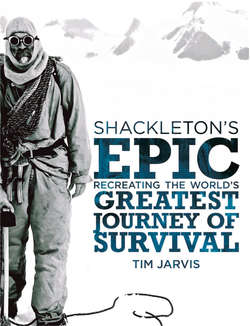

Читать книгу Shackleton’s Epic: Recreating the World’s Greatest Journey of Survival - Tim Jarvis - Страница 9

Оглавление3

WOODEN BOATS

On the high seas: jib and mainsail up at sunset.

Courtesy of Magnus O’Grady

“They traveled in wooden boats but were iron men.”

Anonymous

The reincarnation: our replica boat, the Alexandra Shackleton, at Portland.

Courtesy of Tim Jarvis

The onboard camera showed the gravity-defying sight of bilge water eerily snaking up the wall as the boat turned through ninety degrees, the test mannequin’s neck slumping awkwardly to one side. Within seconds the same water was pooling on the ceiling and the mannequin was dramatically launched upward to join it. From our vantage point, we could see the little boat sitting improbably on her side until, ten degrees beyond vertical, she flipped suddenly onto her topside, her hull left sitting out of the water, glistening in the sun. Gunning its generator, the crane now pulled the Alexandra Shackleton back onto her side until her deck was not quite perpendicular to the water. In a split second she rolled back to normal-looking as a boat should.

We stood watching the capsize test, our feet firmly planted on the quayside of Portland marina in March 2012. At least we now knew the boat could go beyond vertical on its side before capsizing and didn’t need to be quite vertical to roll back over from being fully inverted. In other words, she would reright more easily than she would be knocked down. That was, of course, until one realized that the waves that would help with this would find it difficult to gain purchase on the smooth, rounded hull once she was upside down. Plus the mast and sails would be vertical in the water, anchoring the boat into position. Having no keel was the issue, and capsize along with man overboard were the things we were most worried about. Basically, if the Alexandra Shackleton went over she would be very difficult to right. There would be no keel for a man in the water to grab on to, and even the combined weight of five men below deck would not be enough to do the job. In the meantime, any man exposed to the icy water would lose his ability to swim in as little as ten minutes, his muscles becoming paralyzed by the cold. Nature would have to be our savior with another big wave helping to right her, and that was down to luck.

Ninety degrees from vertical during a capsize test; water improbably snakes up the right wall of the Alexandra Shackleton.

Courtesy of Tim Jarvis

These rerighting difficulties were because the Alexandra Shackleton, like the James Caird before her, was a whaler—a narrow, symmetrical boat with a prow and stern shaped identically, allowing it to be pulled in any direction by a harpooned whale. On such boats, the eight to ten men on board would then row the whale to shore or to a bigger whaling ship, the harpoon trace tied around the sternpost. It seemed fitting that the James Caird should take Shackleton’s men to South Georgia, the home of Antarctic whaling, like a homing pigeon returning to the roost.

The James Caird was built in July 1914 by W. & J. Leslie, boatbuilders of Coldharbour Lane, near West India Docks in London. Commissioned by Frank Worsley, her skipper, and completed to his exact specifications, she was a double-ended whaler, with carvel planking of Baltic pine. This created a flush outer surface as opposed to clinker planking, where the planks overlap. Her stem and sternposts were English oak.

However, she really only became the James Caird we know from Shackleton’s journey after the phenomenal efforts of Henry “Chippy” McNeish, carpenter on the Endurance and “a splendid shipwright.” Helped by others among the crew after Shackleton and his men took to the ice, McNeish raised her gunwales by some thirty-five centimeters, using wood salvaged from the Endurance’s by-then defunct motorboat and nails from the Endurance herself. Shackleton knew very early on that they would have to undertake a sea voyage at some point, so he had McNeish construct whalebacks at each end and fit a pump made by photographer Frank Hurley from the casing of the ship’s compass. It was something that would prove invaluable in the journey ahead.

The same scene viewed by the team standing safely outside.

Courtesy of Tim Jarvis

Because the James Caird was lightly built so as to remain “springy and buoyant” as specified by Worsley, Chippy McNeish knew he had to strengthen her spine to prevent the middle of the boat from bending up and down with the full force of the Southern Ocean, movement that could snap her in half and sink her. To do this he removed the main mast from one of the other lifeboats, the Dudley Docker, and bolted it to the keel of the James Caird to prevent her hull from “hogging and sagging” at sea. Revealing his concerns about the structural integrity of the whaler, McNeish wrote in his diary, “I am putting chafing battens on the bow of the James Caird to keep the young ice from cutting through as she is build of white pine which wont last long in the ice [sic].” All seams were caulked with lamp wick and “paid” with seal blood and artist’s oil paint donated by expedition artist George Marston. This was the first recorded use of artist’s paints as a form of caulk for boat seams.

At Elephant Island, Alf Cheetham and Tim McCarthy created a deck over the boat by stretching canvas over a lattice frame made by McNeish from four sledge runners and packing-case lids nailed together. Worsley recalled how, “frozen like a board and caked with ice, the canvas was sewn, in painful circumstances” by the two men whom he admiringly described as “two cheery optimists.” The bow of the boat had the strongest and most watertight section of deck created by McNeish’s “whaleback,” which extended as far as the main mast. It was masterful work by the carpenter and regardless of his curmudgeonly nature, everyone knew what a fantastic job he had done and how indebted they were to him. Even those who found him most objectionable admitted he had worked “like a Trojan.”

Incredibly, we were not the first to try to take a replica of this twenty-three-foot keel-less boat 800 nautical miles across the world’s roughest ocean. We were, however, going to be the first to attempt it just as Shackleton had, with the same number of men crammed into the boat, using the same type of clothing, equipment, and traditional navigation techniques, and with no modern aids to safeguard against capsize or, in the event that it occurred, to help reright ourselves.

In 2009 Zaz had introduced me to Trevor Potts, a warm, quietly spoken, tough Geordie who, with his three crew, had attempted the “double” in 1993–94. Encountering deadly seas on the approach to Wallis Island, he was forced to sail around South Georgia to the eastern side of the island, landing at Elsie Harbor. The team attempted to cross South Georgia’s mountains from Stromness to King Haakon Bay, doing the reverse of what Shackleton had done, but, due to the complexity of the terrain and a lack of food, they were forced to turn back somewhere near the Crean Glacier. Theirs was an amazing journey nonetheless and one worthy of huge respect.

Trevor was intrigued by the prospect of us attempting the journey in the exact manner Shackleton did, with six men, using only traditional navigation techniques, nonsynthetic materials for the sails and the hull of the boat, and an open cockpit to steer from using steering ropes rather than a tiller. All of these things would make our lives far more difficult, but I was adamant I wanted to do the voyage as it had been done on the James Caird. Add to this the fact the Alexandra Shackleton didn’t have bunks and modern sea gear, and Trevor was impressed, although perhaps quietly skeptical as to whether the journey could really be done this way.

In early 2011, I saw a familiar, stocky figure wandering down the quayside in Ushuaia, southern Argentina. It was a mariners’ crossroads if ever there was one, and, sure enough, there was Trevor. I was there to embark on a recce for our expedition, heading to South Georgia and Elephant Island as a lecturer aboard the ship The World, and he was on another vessel going to the Antarctic peninsula. Like ships meeting in the night—except this was a blustery afternoon in Ushuaia—we chatted enthusiastically and agreed to reconvene in the pub later on. After a few beers the normally reserved Trevor leaned over to me and said with a grim seriousness, “It’s pretty scary out there, you know, Tim—noisy, cold, and rough, and big, big sea. I have to say I really don’t envy you doing this but I wish you all the best and will do all I can to help.” We agreed that when Trevor got back to the UK he would set down some thoughts on what he’d learned from his voyage and what he would do differently next time. As we called it a night, he turned to assure me, and perhaps reassure himself, that there would be no next time for him. The report I later received from Trevor proved invaluable in getting things right on board the Alexandra Shackleton and I am indebted to him.

Where do the people go? Seb’s diagram of the boat’s layout.

Courtesy of Seb Coulthard

Trevor mentioned that two other expeditions had attempted the double—an Irish and a German team—and sent me details. He couldn’t offer introductions but suggested that decent information was publicly available on both, including, in the case of the German Arved Fuchs, his book In Shackleton’s Wake. Former round-the-world-sailor Skip Novak, in the meantime, had supported the Irish, and both he and they were quite open to talking about the horrific experience that team had in the Southern Ocean.

The Irish team’s expedition was called the South Aris and took place in January and February 1997. Their boat was named the Tom Crean in honor of the tough Irishman who accompanied Shackleton after begging to be part of the crew. (Originally Shackleton planned to leave Crean as a reliable right-hand man for Frank Wild on Elephant Island.) The Tom Crean was twenty-three feet long with a seven-foot beam, one foot wider than the James Caird’s. She had synthetic sails, a hull of layered plywood, a tiller rather than steering ropes, and two bunks below deck, but she was certainly no pleasure craft and contained no insulation or padding.

Her tough, five-man crew of seasoned adventurers was obviously pushed to the limit on the voyage, capsizing three times in extremely bad weather (Force 10) on a course that was seemingly taking them east toward the South Orkney Islands. During each capsize, the crew found themselves upside down with the cabin half full of water. Their water-ballast transfer system allowed them to open a valve and transfer ballast weight, offsetting the center of gravity in the boat and rerighting it. That was all that saved them on each occasion. On getting word from their support boat, the Pelagic Australis, that conditions were deteriorating further, the crew abandoned the boat, with the captain the last to leave. His final act was scuttling the boat by drilling holes through the hull so she would sink and not be a danger to other ships. It was a valiant effort we were keen not to emulate.

The other attempt was that of experienced German explorer Arved Fuchs and his three shipmates in 2000. With characteristic Teutonic efficiency, his replica James Caird was called, well, it had to be really, the James Caird II. Although built from the same wood as the original, she too used synthetic sails and opted for a triangular mizzen sail rather than a squarer, gaff-rigged sail as on the original vessel. Like the other replicas, she went for a tiller rather than ropes to steer with, and her crew wore modern wet-weather and survival gear and slept in bunks. Like the Tom Crean, she also had an electronic rerighting system that used water ballast in the event of capsize.

Self-righting systems and tillers certainly made our steering ropes and everyone-lean-to-one-side-and-hope-for-the-best capsize-rerighting techniques seem like evolutionary dead ends by comparison, but we were determined to suffer as Shackleton had, and suffer we would.

Fuchs’s team’s effort was a great one, but on approaching South Georgia in stormy weather and with ice in the water, they opted to be towed into King Haakon Bay. By doing so they compromised the unsupported nature of their attempt, particularly as landing at South Georgia is one of the most difficult elements of the whole journey. We couldn’t be sure the same thing wouldn’t happen to us, as it would likely come down to luck with the weather. And none of us could control that.

Ironically, in among the difficulties of organizing the expedition, building a replica James Caird was, relatively speaking, the easy bit, particularly with the support of the James Caird Society and the existence of the original Caird at Dulwich College. Her life since her famous journey had not been a straightforward one. She had been brought back to England in 1919 and on Shackleton’s death in 1922 was gifted to the college by John Quiller Rowett, Shackleton’s friend and the sponsor of the Quest expedition on which he died. Almost destroyed by a bomb in 1944, the Caird remained at the school barring a period from 1967 to 1985 when she was displayed and underwent restoration at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich.

The Sir Ernest Shackleton

Trevor Potts, 1994

Watercolor by Seb Coulthard

Courtesy of Seb Coulthard

The Tom Crean

Paddy Barry, 1997

Watercolor by Seb Coulthard

Courtesy of Seb Coulthard

The James Caird II

Arved Fuchs, 2000

Watercolor by Seb Coulthard

Courtesy of Seb Coulthard

The Alexandra Shackleton

Tim Jarvis, 2013

Watercolor by Seb Coulthard

Courtesy of Seb Coulthard

Young pretenders: the four replica Cairds to have attempted the journey since Shackleton’s original.

Courtesy of Seb Coulthard

Putting the boat together, clockwise from top left: Les Flack at work on the prow; great white hunters Les Flack and David Philips; master craftsman Nat Wilson working on the Alexandra Shackleton at a traditional boat show.

Courtesy of Tim Jarvis

Zaz called me in 2008, excited at having met Nat Wilson, traditional boatbuilder extraordinaire, at the London Boat Show. She insisted I come meet him the next day and I liked him immediately. Passionate about traditional boats and with the air of someone who knew exactly what he was doing, Nat offered the free services of his college, the International Boatbuilding Training College (IBTC) in Lowestoft, Suffolk. All I needed to do was pay for the materials. Coming from one of England’s best traditional boatbuilders, this was an offer I gladly accepted. Zaz asked me what the boat should be called. “I thought the Alexandra Shackleton,” I said. “If you’re comfortable with that.” She certainly was.

Things progressed effortlessly and the boat was constructed on a trailer that allowed her to appear at various boat shows, where she was worked on in real time in front of fascinated onlookers. Funded by small contributions from individuals captivated by the Shackleton story, she represented tangible evidence that the expedition was on track and progressing well, although that was actually far from the truth. I went to view her a few times during 2009, on one occasion seeing two of Nat’s master craftsmen grinning like children as they proudly posed for a photograph by the curved prow and sternposts as if holding the ivory tusks of a rogue elephant. “As you can see, there’s great enthusiasm for the project,” whispered Nat.

Seb Coulthard had joined the team in August 2010 after Calista Lucy of Dulwich College and the James Caird Society suggested he write to me to apply formally. Because funds were tight and I needed to test the mettle of any applicants, I told him about the need for people to bring either sponsorship money or personal contributions to the table. Four months and 126 letters later, Seb secured a donation of £20,000 that arrived from a corporate backer who wished to remain anonymous. Seb cleared a final hurdle when we finally met at Zaz’s home on March 31, 2011. I was impressed by what I saw: the attention to detail, enthusiasm, and problem-solving ability he applied as a petty officer in the Royal Navy retrofitting Lynx helicopters for different theaters of combat could, I thought, equally be applied to retrofitting a period boat. If he could keep a helicopter in the air, by some convoluted logic I felt he could keep a replica boat afloat on the ocean. Earnest and young but articulate and passionate about Shackleton, Seb convinced me he could project-manage the Alexandra Shackleton into existence.

Seb immediately showed his worth. The Fleet Air Arm (the Royal Navy’s air branch) had formerly operated a helicopter base at what was now John Dean and Richard Reddyhoff’s Portland marina, the soon-to-be-home of the London Olympics sailing competition. Seb asked if we could use the marina to retrofit and sea-trial the Alexandra Shackleton. Richard immediately agreed to let us stay and use the facilities gratis for as long as required—a very generous gesture. A near miss between the Alexandra Shackleton and the Austrian sailing team out on the course a few months later perhaps wasn’t the way to repay his confidence!

When a crowd gathered to welcome the Alexandra Shackleton in Portsmouth on November 7, 2011, a salty old soul, Philip Rose-Taylor, was one of the fascinated onlookers. Amazed that we were going to try to re-enact Shackleton’s voyage, he introduced himself to Seb. Philip was a youthful sixty-nine-year-old, with torn-sail hair the product of a hard life spent at sea, and one of the UK’s last traditional sailmakers.

Seb’s fundraising efforts supplemented what I’d raised and immediately enabled Philip to produce a full set of sails and rigging for the boat. Like maritime detectives, the unlikely duo visited the Caird at Dulwich College. They designed a jib and mainsails and were able to model the mizzen sails on the Caird’s mizzen, the only sail to have survived. Every handmade stitch was perfect and used authentic materials from the period, including flax canvas, flax twine, and Manila rope. Amid the loneliness of planning all the other aspects of the expedition it was a real tonic for me to hear Seb talk about Philip’s expertise in replicating the flat seams, galvanized thimbles, and Manila bolt ropes that Shackleton had on the original Caird. I found their enthusiasm contagious.

In January 2012, Zaz and Seb combined forces to borrow, beg, or steal equipment and boat fittings from suppliers at the London Boat Show. A great double act, they left with a haul that included safety equipment and free training from Ocean Safety, fenders from Compass Marine, and assorted classic-boat fittings such as oarlocks, brass pumps, mushroom vents, and ring bolts from Davey & Co. Seb’s car became a mobile workshop, as full to the gunwales as the Alexandra Shackleton would surely become, and he and his navy colleagues worked long into the winter nights under fluorescent lights, amid overpowering paint, adhesive, and sealant fumes to get the boat ready.

The ribs of the Alexandra Shackleton.

Courtesy of Tim Jarvis

Putting flesh on the bones: the larch planks.

Courtesy of Tim Jarvis

February was given over to producing the rigging, putting the new “old” sails onto the yards and booms, and sourcing pulleys or “blocks” to control the rigging. Again the Royal Navy came to Seb and Philip’s aid by welding iron rings for travelers to enable the sail to be hoisted and lowered on the mast. Authentic blocks from the period were sourced, including one made in 1839 that was reconditioned for the Alexandra Shackleton. Seb tested it and found it could handle a strain of more than 700 kilograms—pretty good after 174 years. Meanwhile the 1,000 kilograms of ballast we required was collected from Portland quarry in 30-kilogram bags, with the van we borrowed to transport it bowing under its strange load.

By now the Alexandra Shackleton had her name stenciled on her bow, so Seb and I agreed to aim for an official launch on March 18 in order to have her sea-trialed during the northern spring and ready for training during the summer. Once committed, we spread the word and locked in the date. I booked flights from Australia to come spend time undertaking capsize drills, working on the boat, and continuing to lobby for funds.

Because he had spent so much time working on the boat and knew he’d be away for months during the expedition, Seb undertook a domestic policy initiative to fit a new kitchen at his home as compensation. A simple slip while operating a circular power saw left him with a 1.5-centimeter-deep, 10-centimeter-long cut across the back of his left hand. Luckily no tendons were severed, but he required hours of surgery. In typical fashion, Seb’s concern was not so much for his hand but for how he would get the boat finished by the launch date. Not wishing to burden me with it, he never told Zaz or me what had happened, instead enlisting the assistance of Paul Swain, Dean and Reddyhoff’s assistant manager, who had already been a great help to the project. A fine sailor and can-do guy, Paul took on a huge workload and, with Seb’s agreement, put an advertisement in the local paper requesting volunteers: engineers, boatbuilders, carpenters, and anyone else able to pick up a brush, drill, or hammer.

Maritime detective and expert traditional sailmaker Philip Rose-Taylor, hard at work.

Courtesy of Seb Coulthard

Finishing his kitchen with no further misadventure, Seb arrived at the marina in early March to find a group of fourteen volunteers from the local community patiently waiting to be assigned tasks. Seb thanked them profusely for coming and asked each in turn why they wanted to be involved. Without prompting they all gave a single-word answer: “Shackleton.” It was a powerful moment and showed how the legend of the explorer and his achievements remained undimmed with the passage of almost a century. Among this gang of honorary shipwrights were doctors Philip Ambler and Robert Goodhart; two qualified boatbuilders, Ian Baird and Fiona Lewis; local photographer Scott Irvine; Dave and Jackie Baker; and the charming Yvonne Beven, whose house became a home away from home during the sea trials. All were tireless workers for whom no job was too big or small.

Robert Goodhart took charge of fitting the life raft and preparing the safety equipment on board. Philip Rose-Taylor set about rigging the boat and erecting the shrouds. Slowly an empty hull began to turn into a mighty craft. Fiona Lewis helped Philip get the sails on board and rigged with sheets and blocks, while Philip Ambler and Ian Baird took charge of fitting toe rails and oarlock chocks. Seb, in the meantime, wisely did anything that didn’t involve power tools, given his recent track record.

Twelve days of what Seb called “expedient engineering” followed, with the team of volunteers working around the clock under the guidance of Seb, Paul, and Philip Rose-Taylor. Seb joked that the spirit of Chippy McNeish was among them during those feverish days of improvisation and working to a tight budget funded largely by my mortgage. Each time they came up with a novel solution to a problem—including, on occasion, using recycled materials—the call would go up, “We’ve McNeished it!” (Of course they never took shortcuts if it meant compromising safety or performance.) The final piece to be fitted on board was the hatch. Given how hard it was to open, it seemed appropriate that an outfit called Houdini Marine made it. Too fiddly for numb hands in the bitter cold of the Southern Ocean, we replaced it with something with bigger, easier-to-grasp handles.

The launch date came around quickly. Unless you looked very closely, the Alexandra Shackleton was essentially finished, a great testament to her hardworking team. It was amazing to see her transformed from the basic shell of a boat Nat and I had project-managed. Now she was the James Caird in all but name. Zaz, dignitaries, Shackleton supporters, and a large crowd of onlookers were at the launch event, with Baz Gray, our second recruit, and Seb in full military regalia. The skipper of our proposed support vessel was notably absent. It was a surprise to all of us and almost certainly a bad omen.

Neptune, god of the sea, we ask that you record our boat’s name in your “Ledger of the Deep.” . . . Let it be recorded, that on this day, Sunday 18th of March 2012, and forever more, this fine vessel shall be named Alexandra Shackleton. May God bless her and all who sail in her.

It was the kind of ceremony Shackleton would almost certainly have enjoyed and approved of, with Zaz laying a branch of green leaves over the deck to remind the boat that she must always return to port and Trevor Potts placing a silver coin under the mast for luck. We dispensed with breaking a champagne bottle over the prow for fear of damaging Seb’s handiwork, instead splashing some of its contents on the woodwork and consuming the rest, feeling Shackleton would have approved. We toasted the four winds, but secretly I hoped for just three—easterly winds, we didn’t need.

The next few months consisted of Seb continuing with sea trials and buying gear and equipment together with Paul Swain and Philip Rose-Taylor. I meanwhile returned to Australia to focus on fundraising and organize broader expedition logistics, which were now consuming all of my available time and energy. As we each focused on our niches, I left the Alexandra Shackleton in Seb’s capable hands. He became totally immersed in old sailing technology and language, telling me on one occasion with great pride that he’d fixed a leak to the “port aft garboard strake.” I was glad but had absolutely no idea what he was talking about.

Trevor Potts placing a silver coin under the mast for good luck.

Courtesy of Nick Smith

Seb was a master of detail, not only sourcing period gear and equipment and establishing its provenance but taking the time to test its adequacy for the conditions. For example, our 1916 Elgin pocket watch was bought, repaired, waterproofed, and tested in a freezer to -20˚C (-4˚ F) for twenty-four hours. Gear appeared steadily, with great stories attached to much of it, adding to the romance of the expedition. Captain Bob Turner, RN, a former captain of the ice patrol ship HMS Endurance, donated a Sestrel sextant similar to the Heath Hezzanith sextant used by Huberht Hudson, Shackleton’s navigator on board the Endurance. We also acquired an E Dent compass filled with alcohol to prevent it from freezing, which was made by the same family as the original chronometer carried on the James Caird. And it was virtually identical to the one used by Frank Worsley.

It was an odd juxtaposition of old and new. As Seb, Paul, and Philip put in place hundred-year-old gear, Ed from Raw TV, together with marine electrician Robert Sleep, went about fitting the fixed camera rig of standard and high-definition cameras that would not have been out of place on a space shuttle. According to Ed, it was by far the most complex camera rig ever fitted to a boat of this size (and probably the most expensive).

Old and new: (left) the 360-degree infrared camera and (right) the 174-year-old wooden block.

Courtesy of Tim Jarvis

In June the Olympic Games sailing events began moving in to our Portland home, so the Alexandra Shackleton was relocated to Weymouth Marina. Best to distance her from the sleek modern Olympic boats that served only to remind us the Alexandra Shackleton wasn’t going to win any races. More and more modern equipment now went into the boat, but none of it would give us an advantage over Shackleton—it would merely allow us to record the experience for Discovery Channel and the American PBS network. In fact, if anything, the equipment could have been seen as a disadvantage, significantly reducing the space on board while increasing electrical hazards and fire risk. Three-quarters of the carefully placed stone ballast was replaced with 560 kilograms of compact marine gel batteries, each putting out 413 amps, followed by an Automatic Identification System (AIS) transponder, chart plotter, radio, antennas, and EFOY fuel cell. God only knows what Shackleton would have made of it all.

By now Seb had commissioned a leading marine technology unit, the Wolfson Unit at Southampton University, to undertake stability calculations for the Alexandra Shackleton. There were two goals: we needed to know how to best position our ballast to safeguard against capsize and to understand what the chances of rerighting the boat would be if she did go over. The summary of their report spoke volumes:

The calculations demonstrate that the boat is not inherently self-righting. The James Caird capsized but did not remain inverted because of dynamics of the event. These calculations indicate a strong likelihood that, if the [Alexandra Shackleton] suffers a capsize and remains inverted, some action by the crew contained within the boat will enable them to right it. The scope for movement of the crew will depend on the arrangement of stowed gear and stores, and their ability to lift themselves upwards within the inverted boat. It may be desirable to conduct some trials with the boat loaded as for the proposed voyage, to quantify the level of ease or difficulty of righting the boat in this way. The consumption of water and stores will reduce the stability, and it may be desirable to counter this by filling empty containers with sea water as the voyage proceeds.

In other words, without extensive trialing we wouldn’t know. What we did know was that any serious attempt to reright ourselves would require us to get ourselves as high off the ceiling as possible and hope the next wave pushed us back over. We had no sensible way of re-creating waves big enough to roll and reright the Alexandra Shackleton and the test sling being used to tip the boat wouldn’t accurately re-create waves anyway. All of our energy would instead have to be put toward trying to ensure we didn’t capsize.

In early August 2012 the team consisted of Ed Wardle, Seb, Baz, Paul Swain, and me. What were worryingly and noticeably absent to even the most casual of observers were Southern Ocean sailors. I’d lined up a series of top-notch candidates and spoken to them from Australia. Now I had to interview them in person and conduct a week of sea trials off the south coast of England to determine how well they gelled with the rest of the team. Our August sea trials therefore became as much about fine-tuning the six-man crew as about assessing the boat’s seaworthiness.

With the completion of the last few jobs of fitting the compass rack in the cockpit and stowing the handmade wooden boxes containing provisions, charts, and books, we were ready to go to sea. Initial trialing began in early September in Portland’s sheltered harbor, then the plan was to take to the open sea, heading east from Portland to Southampton, a distance of 100 kilometers. Seb had arranged for me and a BBC cameraman to ride in a Fleet Air Arm Lynx helicopter from Yeovilton to Portland to film her in action. As we thundered overhead I found myself looking straight down on the Alexandra Shackleton as we banked steeply, the wide open space beckoning through the open doors. The pilot’s voice came over my headphones. “Want to go closer in?“ he asked. “Yes,” I replied, suggesting that we give the crew below a friendly blast of down-force from the rotors to re-create Southern Ocean conditions. He obliged with glee. Forty or so meters below us, the Alexandra Shackleton shook uncontrollably as she was buffeted from side to side. “You’re going where in this?” asked the copilot incredulously as we moved away from the boat. “Antarctica,” I replied. He and the pilot glanced at each other but said nothing.

The following evening, we were ready to begin trialing the Alexandra Shackleton in open water. It had taken most of the day to load her with provisions and water and go through final equipment checks. The plan was to meet and trial different potential skippers and navigators as we went east, stopping along the way to take on and drop off people. The first rendezvous point was picturesque Lulworth Cove, twenty-five kilometers to the east. Far from being an easy place to trial a boat, England’s south coast has very strong tidal currents that run along it in either direction. We knew that at certain points, such as the Needles, we might even get a feel for how stable she was in big waves.

In order to meet our first potential skipper at Lulworth, we had to avoid going too far east the first evening. But a strong tide was working with us and, sure enough, even with sails trimmed and trying to tack back toward Portland as best we could, we moved eastward at several knots an hour until, in rapidly fading light, a telltale piece of flotsam passed us heading back to the west. With that, we realized the powerful tidal conveyor had turned and was beginning to push us back toward Portland. To prevent too much westerly drift all the sails now went back up, working fine initially as we trod water, the wind and current canceling each other out until the wind dropped completely about 1 A.M. Inexorably invisible forces pulled us back toward the dark, unlit band that signified Portland’s rocks. It was as if we were caught in a whirlpool that wouldn’t release us from its grasp until dawn, which was still four hours away. Eight miles off Portland’s breakwater, the city’s lights twinkling in the darkness, we realized we’d done too good a job of slowing our easterly drift—we would be on the rocks in less than three hours. It was time to take to the oars as a last resort to row east and buy some time. Baz and I leaned into them, he at the bow, me at the stern. Then, after less than five minutes of rowing, a loud crack signaled that Baz had broken his oar. Initially we laughed at the ridiculousness of the situation, but when my oar followed suit ten minutes later, we became slightly nervous. We had just one functioning oar left to keep us off the rocks (the other had a crack in the blade and a makeshift repair because we thought we’d have no need for it).

Only a long three hours of work on the oars kept us from the rocks that night as Baz and I, with some relief from the others, worked hard to balance the conflicting needs of applying power while safeguarding our last oar. At the first light of dawn, a slowing of our movement westward signaled the tide was finally going slack. Our distance from Portland’s rocks was less than a mile. This wasn’t even the Southern Ocean. It was Southern England and already we’d been put through our paces.

A proud patron: the Hon. Alexandra Shackleton and her namesake.

Courtesy of Chris Mumby