Читать книгу Surfing about Music - Timothy J. Cooley - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

Riding a wave—surfing—is a cultural practice. Surfing is a deeply experiential act of playing with the power of wind that has been transferred to water to form ocean swells. Sliding down the face of a moving aqueous mound that is forced upward as it approaches shore, a surfer engages with the forces of gravity and water tension. Using techniques handed down through countless generations of coastal dwellers, the surfer harnesses the wave’s energy to move over water in a dance across that liminal zone between open ocean and wave-lapped land. Surfing is a balancing act on a watery tightrope stretched between a silently rising swell and a thundering breaking wave. Yet no matter how much skill, strength, and grace the surfer displays, no matter how small or large the wave that propels the surfer, in the end surfing leaves no trace on the water’s surface. Wave riding creates no lasting product save a memory, a kinesthetic impression.

In this way surfing is like music, for sound waves vanish the instant they are heard. Both surfing and musicking1 are ephemeral cultural practices that have no quantifiable results or functions other than the feelings they may engender, and the meanings given to them by people. Surfing and musicking require much more time and energy than is reasonable if their purpose is to achieve basic material needs. We clearly engage in them for other reasons. Yet even if we believe passionately that surfing and music are imbued with great meaning, we may not always be able to articulate what that meaning is. Let’s sing another song . . . I’m going to catch one more wave . . .

This book is about surfers and the types of music that they create and associate with surfing. But I need to be clear about which surfers I am attempting to interpret and represent. Surfers form a global affinity group, but as with any group of people, no statement or claim can be true for every individual in that group. We could conceive of surfers forming any number of distinct affinity groups globally. The stories I tell here are illustrative of surfing communities that I have access to: primarily cosmopolitan surfers from California, Hawaiʻi, Australia, Italy, and the United Kingdom, with much more limited input by surfers from other points on the globe. These surfers are global—collectively they have surfed at the best surfing beaches around the world—but they still represent relatively affluent cosmopolitanism from North America and Europe more than the cultural sphere on any given beach in Indonesia, for example. To put it another way, dozens of surfers—some of them very influential in my posited global surfing affinity group—have contributed to this book, but that still leaves millions of surfers worldwide whose voices are not represented here.

This is a deeply personal book. I have aspired to ride waves and to make music since I was a child, and being a surfer and a musician has been an important part of my self-identity since my early teen years. Therefore, readers will notice that my authorial voice changes from time to time from that of writer-scholar to that of surfer-musician. In particular, I shift to the first-person plural pronouns we and us occasionally and talk to the in-group tribe of surfers—a community I invite you to join if only for a moment. Come in . . . the water is nice.

The critical scholar in me knows that the “I” and “we” here have very limited experience in the context of globalized surfing. I grew up surfing in Virginia and Florida before moving to California. I also spent about a decade living in Illinois, where I would surf in the chilly waters of Lake Michigan. Once I encountered another surfer at my local Chicago-area break, but only once. Beyond the mainland United States, I have had the pleasure of surfing in Mexico, Hawaiʻi, Australia, and the United Kingdom. Yet my experience with surfing—and with musicking—is individual. My experience is also highly mediated. As with every surfer-musician I interviewed for this book, my experiences are influenced by commercial interests. By this I mean that even the private pleasure of riding a wave is not pure and unaffected by the entertainment industry and other commercial concerns that use surfing as a marketing tool. For example, I am told what I should feel when catching a wave by an old Beach Boys song, just as I am reminded by the latest issue of Surfer magazine that I would look much better in a new pair of boardshorts.

This book asks two interrelated questions: First and foremost, how is music used to mediate the experience of surfing? And second, how does surfing, and changing notions of what a surfing lifestyle might be, affect surfers’ musical practices? Through my interviews and analysis, I find that music is necessary for making sense of surfing, for communicating important information about surfing, and for creating a collective space where surfers communicate together something of the experience of surfing. All of these uses of music by surfers help to form and define surfers as an affinity group.

WHAT DOES MUSIC HAVE TO DO WITH SURFING?

In a feature story in Surfer magazine, Brendon Thomas wrote, “The connection between music and surfing is undeniable,” and Surfgirl Magazine editor Louise Searle described how “[s]urfing and music go hand in hand: like Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, strawberries and cream, and vodka and tonic—they’re all better together.”2 Surfing has even been (incorrectly) called the first sport with its own music.3 The notion that music and surfing somehow naturally go together seems to be gaining traction.

Four recent films offer very interesting takes on the topic of surfing and musicking.4 The first is Pounding Surf! A Drummer’s Guide to Surf Music, produced in 2006 by musicians Bob Caldwell, Paul Johnson, and others. Though this film was first envisioned as a primer on playing drums for instrumental rock, it evolved into an elaborate filmic history of early 1960s California surf music and its ties to Southern California surfing culture. Also released in 2006 was Australian surfer Dave Rastovich’s Life Like Liquid, consisting entirely of footage of surfers improvising music together, interspersed with clips of the same people surfing and musing about the relationship between musicking and surfing. In 2008 two additional films were released on the subject. Live: A Music and Surfing Experience, produced by California-based surfing film maker David Parsa, is a wide-ranging look at music and surfing that contains brief comments by leading professional surfers, surfing industry icons, and popular musicians. The fourth film, Musica Surfica, by Australian surfer and filmmaker Mick Sowry, is a curious and at times perplexing meditation on Australian Chamber Orchestra director Richard Tognetti’s genre-expanding violin playing interspersed with Derek Hynd’s quiver-expanding challenge to design and ride finless surfboards. Taken together, these four films spin an intriguing tale about the interweaving of the human performative practices of surfing and music-making. The first sticks close to the named genre Surf Music and captures a key moment in the history of surfing’s reinvention in the twentieth century. (I capitalize the term Surf Music to indicate that I am referring to a specific genre and not all music associated with surfing.) The second is an extended experiment to see what would happen if surfing musicians were cloistered together for some days. The third is an expansive survey of music performed and endorsed by influential modern surfers. The fourth reminds us that both surfing and music-making cannot be limited to the narrow practices celebrated in surfing contests and by popular media.

Music and surfing are mixed and matched in many other ways. Festivals that combine some aspect of surfing and music are popping up around the world in obvious locations like Hawaiʻi and California, but also in places such as the United Kingdom, Portugal, France, Italy, and Slovenia. Surfing magazines routinely list professional surfers’ favorite music, review music albums, promote concerts and music festivals, and publish feature articles on surfing musicians.5 Surfing brands such as Quiksilver promote musicians, include music-related products in their lines, or, in the case of clothing company Rhythm, imply music in their brand name. Much of this is business as usual. Rare is the festival without music, and commercial industries long ago figured out that music was a compelling way to boost and sometimes define their brand images. While this phenomenon is not unique to surfing, the use of music by the surfing industry tells us something about how the industry interacts with and manipulates surfing communities.

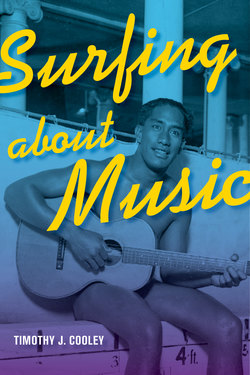

More striking, however, is the surprising number of former and even current professional surfers who have second careers as popular musicians. This includes, most notably, the eight-time platinum-album-selling surfer-musician Jack Johnson, from Hawaiʻi; three-time world surfing champion Tom Curren, from California; two-time world longboard champion Beau Young, from Australia; two-time women’s world longboard champion Daize Shayne, from Hawaiʻi; free surfer Donavon Frankenreiter, from California (fig. 1); and other surfer-musicians featured in chapter 5 of this book. There are also professional musicians of all sorts who are passionate about and draw inspiration from surfing, including popular musicians Eddie Vedder, Jackson Browne, Tristan Prettyman, Ben Harper, Chris Isaak, Brandon Boyd of Incubus, and Metallica’s Kirk Hammett and Robert Trujillo.

FIGURE 1. Surfwear company Billabong’s “Only a Surfer Knows the Feeling” ad, featuring surfer-musician Donavon Frankenreiter, that appeared in the Fall 2010 issue of the Surfer’s Journal. Reprinted with the permission of Burleigh Point, Ltd. dba Billabong USA.

But is there anything inherently musical about surfing? Is the relationship between music and surfing—taken for granted and celebrated by insider surfing media and films—real and meaningful, or is it a myth propagated by that periodically revived genre labeled Surf Music from the early 1960s (the Beach Boys: but more to the point, that “King of the Surf Guitar” Dick Dale)? Or are these the wrong questions?

They are the wrong questions. Rather than asking if the connection made by some musical surfers between musicking and surfing is real or mythical, it is more satisfying (not to mention ethnographically appropriate and productive) to accept those connections as meaningful cultural constructions that must be taken seriously. Surfing is a cultural practice; its development, style, and, ultimately, meaning are all expressions of human creativity. Making and listening to music are also cultural practices that, like surfing, are expressive of the human condition. Yes, listening to music is an expressive practice; it is an activity not that far removed from making musical sounds oneself. In many ways music is in the listening. The same sound may be heard by one person as music and by a second as noise. Choosing what music we listen to, get into, dance to, worship to, compose, and share with our friends is one of the ways we create who we are as individuals and as groups. The decision to play in the water, to lie, kneel, or stand on a surfboard, and the riding styles we imagine and achieve are also part of who we are as individuals and groups. We can spin this out indefinitely: the size and shape of the surfboard you choose suggest something about your style and skills (or aspirations), as do the color and cut of your boardshorts or bikini. Likewise, the instrument you play and the outfit you wear when performing suggest ideas about the sounds you intend to make even before you begin making music.

Let’s stick to surfing and music generally for the moment. Any individual’s and group’s ideas about meaningful relationships between these cultural practices and others form part of that individual’s and that group’s cultural identity. It is part of who they are and the identities that they create for themselves. When an individual proclaims that he or she makes music this or that way because of religious beliefs or ethnic heritage, we tend to take that seriously. Surfing may or may not hold similar cultural weight for any given wave rider, but we owe it to surfers to take seriously the connections they make between their musicking and surfing. The music that surfers associate with surfing is key to what surfing is, or rather the many things that surfing is, as well as to who surfers are and aspire to be. This is what this book is about. This is why making music about surfing and surfing about music is serious business.

AFFINITY, COMMUNITY, AND THE SURFING LIFESTYLE

Since the essence of surfing is one person dancing with the power of an ocean (and occasionally smaller bodies of water), the sport lends itself to individualization. Yet while a modern trope is that the surfer would just as soon surf alone, surfers (like all other humans) seek communities of like-minded people. Sometimes in some societies this may begin by surfers saying what they are not. As Belinda Wheaton notes in the introduction to her book Understanding Lifestyle Sports, surfers and participants in other lifestyle sports may deliberately seek to challenge existing orders by being transgressive.6 Yet even transgression seeks company. Challenging and transgressive behaviors soon form the basis for a new identity group and even a community of sorts.

Surfing did not start out as transgressive behavior; it originated with seafaring islanders who probably first enjoyed the boost from waves when they returned to shore with a vessel full of fish. Before Europeans and North Americans sailed to Hawaiʻi, surfing was practiced and celebrated by all segments of Hawaiian society. In the early nineteenth century, Calvinist missionaries to Hawaiʻi instilled the still-prevalent view that surfing was unproductive and a waste of time, necessitated nudity, and was thus sinful. Much less common in Hawaiʻi at the turn of the nineteenth into the twentieth century than it was a century earlier, surfing quietly took root in California and then spread around the world, but it carried with it some of the taint of transgression given it by missionaries in Hawaiʻi. Of course that hint of danger and rebellion suited some midcentury surfers, and later became an attractive (to some) quality of skateboarding and snowboarding, both descendent board-sports first developed by California surfers. Globalized surfing today continues to cultivate the image of danger, independence, and subcultural edginess.

Embraced by some but resisted by others, a term frequently used by surfers today to refer to a surfing community is tribe.7 The term captures some of the tensions between individualism and a desire or even need for community. Tribe sounds a bit out of place in many modern societies, and suggests a collective that is somehow different from—and slightly threatening to—any given mass society. A tribe is only slightly more respectable than a gang in popular usage. Yet tribe also suggests desirable qualities. A tribe is inclusive (women, men, and children of all ages are welcome and needed in a tribe), has some sense of heritage and history, and of course has rituals. An e-mail message I recently received from the California Surf Museum promised such a tribal ritual. It began: “Join the tribe—come celebrate Surfer magazine’s 50 years . . . ” The celebration would be a gathering of the tribal leaders, yet even lowly villagers like me were invited. By attending the celebration, one could ritually reaffirm one’s own membership in the surfing affinity group—the tribe—and at the same time distinguish oneself for a moment from the rest of society.

Surfing is all about balance. Navigating the inherent individuality of surfing itself and the human need to form communities requires balance. Any discussion of surfing communities must seek to balance the contradictions and contrasts that make them what they are. In his book Dancing the Wave, Jean-Étienne Poirier writes with poetic power of these contradictions: “Surfing is the center of a sphere where some values evolve in one direction while others move in the opposite: sometimes the image of surfing is gentle and romantic, with a setting sun and surfers with magnificent smiles; sometimes it is war-like and violent, with illustrations of titanic waves that leave no room for refinement and delicate dance moves. . . . Because opposing forces together create gravity, surfing remains in motion.”8 Surfing communities need the solitary surfer seeking empty waves,9 as well as the local surfer who surfs the same spot whenever the waves are up with the same group of friends, and even the surfer who rarely gets wet but who dreams of the perfect ride. All are part of a surfing tribe; the internal contrasts and oppositions are part of what keeps that community vital.

Frankly, I also need there to be some sort of vital community for this book to make any sense. To approach music as an ethnomusicologist, I need a group of people making and consuming music. As the prefix ethno- suggests, the discipline of ethnomusicology is very concerned with group identities, often defined as ethnicities. My study of music and surfing is in part a critique of my discipline’s obsession with the increasingly problematic divisions of individuals into politically defined ethnic categories.10 The posited global affinity group of surfers that I am writing about here challenges the sorts of subjects that make up the stock-in-trade of ethnomusicology: groups that form around shared heritage, religion, regions, occupations, and so forth. Here I find more useful recent theories of elective communities—from “cultural cohorts” to “affinity groups” and “lifestyle sports.”11

Surfing is arguably the prototypical lifestyle sport—a sport that can be distinguished from what are called in sports studies “achievement sports.” Achievement sports are those typically taught in institutions (for example, football, rugby, baseball, track, and wrestling), and they emphasize teamwork and competition. Lifestyle sports are also called many things, including “alternative sports,” “new sports,”12 and, especially in the United States, “extreme sports,” as promoted in ESPN’s X Games.13 Windsurfer and sports scholar Belinda Wheaton prefers the term lifestyle sport because in her ethnographic research she found that this is the term that participants themselves used and that they actively “sought a lifestyle that was distinctive, often alternative, and that gave them a particular and exclusive social identity.”14 My ethnographic work with surfers agrees with Wheaton’s—play (playing music, sports play, and so forth) and lifestyle choices are ultimately about core issues of identity. For example, surfing musician Brandon Boyd of the band Incubus does not like to consider surfing a sport but rather a lifestyle.15 Similar debates about whether surfing is a sport or an art have been going on since at least the 1950s.

To take on a surfing lifestyle is a voluntary proposition; it is to enter an affinity group. Affinity groups form around volunteer participation in cultural practices rather than through the genetic, heritage, or location ties (sometimes called “involuntary affiliations”) that drive most discourses on ethnicity. In some cases, affinity groups may become ethnicities over time; for example, certain religious groups tend toward this progression. Other affinity groups briefly burn brightly and then disappear or move into a subcultural scene. Individuals may move into affinity groups at will, perhaps lingering for some time and then moving away, reframing their identity with other affinity groups, or even as former members of an earlier group: “I used to be a surfer . . .” Surfing is demanding, however, in that a reasonably high level of fitness must be maintained if one is to participate. As Wheaton notes, with most lifestyle sports active participation is key. Still, even deep involvement in a sport may be just a part of any individual’s multiple identities. This is an important quality of what I am calling affinity groups. An individual may move in and out of several affinity groups, even daily. For example, seeking job security, I hid my identity as a surfer from my colleagues in the music department during my first years as a professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, but then would surreptitiously shift into my role as a surfer as I walked the few hundred feet from my office to Campus Point to go surfing. As we all do in our everyday lives, I performed different versions of myself—or foregrounded certain identities—depending on the demands of the moment.16

There are three primary characteristics of affinity groups as I am using the term. First, a cultural practice draws the group together: a particular type of musical practice, a penchant for dog shows, a love of gardening, or a singular dedication to participating in a sport. Second, the most salient feature of an affinity group is that the individuals in the group are connected by desire—not by obligation born of family ties, religion, place of origin, shared history, or anything else. Yet more often than not such groups invent histories, origin myths, family ties, and even a sense of spiritual connection that approaches religion. Third, since participation is driven by desire, it is also voluntary and often temporary, as already noted: members may leave the group at some stage, or move in and out of the group. One can imagine cases where desire leads to voluntary participation that then becomes involuntary through the compulsion of addiction or even economic necessity. Thus even affinity must be seen as a sliding, fluid notion, perhaps a point on a continuum somewhere between attraction and obligation or addiction.

THE FEELING OF SURFING: ONLY A SURFER KNOWS

It is an article of faith among many surfers that only a surfer knows the feeling of, well, surfing. The phrase “only a surfer knows the feeling” has been used as a successful advertisement slogan by the Billabong surfwear company, and is uttered by surfers regularly (much to the delight of Billabong; see fig. 1).17 Both my conversations with surfers and items written by surfers reveal that the meaning of the phrase goes beyond the tautology that only surfers know what it feels like to surf. Surfers describe feelings of euphoria from surfing, and this feeling is often spoken of in mystical terms: they speak of its healing power, and some find surfing spiritually redemptive. Steven Kotler takes a long look at the feelings of euphoria and spiritual awareness that surfing generates in his book West of Jesus: Surfing, Science and the Origin of Belief.18 He discovered that similar feelings of euphoria and spiritual awareness were generated by a range of extreme experiences, not just by surfing, but he starts and ends with surfing, as I do here.

The feeling of surfing is summarized by some surfers with two related but distinct terms: stoke and flow. According to Matt Warshaw’s Encyclopedia of Surfing, the term stoke comes to English from the seventeenth-century Dutch word stok, meaning to rearrange logs on a fire or add fuel to increase the heat. Surfers adopted the term in California in the 1950s. As its derivation suggests, it means to be fired up, excited, happy, full of passion. As a description of emotional experience, stoke is complemented by another term, flow, suggesting an obvious kinesthetic play of moving bodies—the movement of water and the movement of the surfer through or over water. But flow goes beyond the obvious and into the realm of optimal experience, as theorized by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi in his book Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience.19 As Csikszentmihalyi explains, the mental state of flow is achieved through intense focus and concentration so that distractions disappear and one feels in harmony with one’s surroundings and oneself. One can experience flow when doing any number of things (including the antithesis of surfing for most surfers: working). However, I suggest that three definitive qualities of surfing create flow, and the interrelated feelings of stoke. These qualities help explain why so many surfers try to express or even replicate that surfing feeling (emotional and embodied) with music. These qualities are risk-taking, waiting, and submission.

The first definitive quality of surfing is risk-taking. The cultural act of surfing takes place in the highly volatile liminal zone between open ocean and dry land (see fig. 2). One rides a wave along a thin line of transition between a harmless swell and the dangerous impact zone of a crashing wave; the zone of bliss is balanced between safety and despair. In that zone, one generally does not make music; even conversation is minimal. Instead, it is a place of waiting and watching for the choice swell that will become the crashing wave of a surfer’s desire. Once a surfer has caught the wave and is up and riding it, she or he often compounds the risks. Experience-enhancing maneuvers, such as seeking speed in the steepest sections of a breaking wave, or even stalling to place oneself in the volatile barrel of a wave that pitches its breaking lip out over the surfer, puts the surfer at risk of a violent wipeout. It is much safer, if less exhilarating, to ride well ahead of the breaking whitewater, and to kick-out (exit) the wave early. And many surfers seek ever-larger waves that occasionally prove deadly for even the most experienced.

FIGURE 2. The liminal zone of surfing. Photograph by Chris Burkard (burkardphoto.com).

Waiting is a second quality that defines surfing, and perhaps surfers. Surfers must wait for swells, preferably generated several thousands of miles away so that the strong winds that created them are not present when the waves reach the surfers’ beach. No beach offers waves on demand. In his book Dancing the Wave, Jean-Étienne Poirier wrote that “[t]he sea has no schedule; it must be taken when it offers itself. It has its moods, and it is the surfer who must yield and accommodate them.”20 Thus, like a coy lover, the sea plays with its surfer courtiers, withholding favors or offering them at awkward times that demand sacrifice. No wonder some surfers will cancel appointments, miss work, and skip classes when the waves are good—a tendency celebrated in Holland-based surfing brand Protest’s “Drop-It-All” ad campaign (fig. 3). In my own experience, surfers struggle to balance school, jobs, relationships, families, and domestic duties with their love for the fickle ocean. Still, there is some truth in the stereotypes of surfers who are unreliable when the waves are good. The unpredictability of surfable waves does distinguish surfing from many other sports where one might schedule an outing unless the unpredictable happens (we will ride bikes Friday afternoon, unless it rains . . . ). Instead, the surfer waits for the unpredictable, the unusual—for most places—weather conditions that produce good waves.21 The surfer waits.

When the waves are good, the surfer waits again. Only the inexperienced surfer rushes into the ocean upon arrival. The seasoned surfer knows to wait—wait and watch. Read the pattern of waves and wait for the optimal time to enter the water and to paddle out through the dangerous impact zone to the spot where you anticipate catching a wave. Once outside, wait for a good set (a group of waves; ocean swells usually arrive in sets of three to five waves). Rarely is the first wave of a set the best. Less experienced surfers will scramble for the first wave, clearing the lineup (a group of surfers in position to catch a wave) for those who wait. When other surfers are out, one might need to wait one’s turn in the complexly negotiated lineup. If you don’t find your place in this set of waves, wait for the next. There’s always another wave for those who wait (fig. 4).

FIGURE 3. “Drop-It-All Sessions” ad campaign by surfing brand Protest that appeared in Huck 3, no. 15 (2009).

FIGURE 4. Surfers in Lake Superior waiting for the right wave. Photograph by Shawn Malone (LakeSuperiorPhoto.com).

A third quality in surfing is submission. The ocean is the surfer’s mistress/master and teacher. The wise surfer asks for permission to surf and never makes demands. Legendary Hawaiian surfer Paul Strauch says that he always pauses by the ocean before entering the water as he seeks permission to surf. Even when the waves are very good, if he does not sense that permission is granted, he turns around and leaves.22 Generally, however, when the waves are good, the surfer submits to the call of the ocean and, once in the water, submits again to its unbounded power. As mentioned above, a surfer must put himself or herself in harm’s way in order to catch and ride the wave. One must submit to the wave’s power, then work with—play with—that power to achieve the optimal ride or flow. The same is true when one falls while surfing—when one wipes out—especially in large waves that can twist and turn a surfer, holding her or him down for long periods. Every experienced surfer knows that there is no sense in fighting the ocean. When it is ready, the ocean will release you, and you will float or swim to the surface for air. The best survival technique is to relax, wait, and submit.

Perhaps for these reasons, surfing leads some to become contemplative—waiting for signs, listening to nature, thinking about and submitting to mysterious forces. In return, many surfers seem to find healing and even redemptive qualities in surfing, both physical and psychological. This is a common (though hardly universal) theme in surfing literature.23 The contemplative quality of surfing also leads many to talk about surfing in spiritual terms. The first decade of the twenty-first century saw an impressive output of books on surfing and spirituality.24 Comments and even feature articles about surfing and spirituality also regularly crop up in surfing magazines, such as the article in Surfer, titled “Is God a Goofyfoot,” in which Brad Melekian asks a Catholic priest, a Christian pastor, a Jewish rabbi, and a Buddhist monk if surfing itself might be a religion.25 (His conclusion is that it is not, but that it can be a powerful spiritual and meditative practice.)

In my experience as a surfer, and in talking with other surfers, I’ve concluded that those who keep at it for some years tend to find the practice of riding waves to be a deeply but inexplicably satisfying experience. Personally, surfing adjusts my attitude, removes anxiety, and provides a level perspective on dry-land problems and pleasures. A Christian myself, I have a practice of surfing after church Sunday mornings, a tradition I only half-jokingly call the sacred ritual of the post-Communion surf. Sometimes this sacred ritual is more spiritually satisfying than Mass itself.

The contemplative possibilities of surfing may also lead some surfers, though not all, to seek musical expression. Other surfers are more focused on the adrenaline boost surfing can provide, and this inspires their musicking (something that Dick Dale claims, as I will show in chapter 2). There are many reasons and ways that surfing might encourage musicking among some, but in most cases, surfing and musicking are enacted in different spaces/places/locations. On dry land—even on damp, wave-swept beaches—there is only memory of the adrenaline rush, the search for oneness, the healing power, the spiritual redemption, and so forth that motivates the surfer. There on the beach surfers try to recapture some of the feeling of being in the water, surfing. They swap stories about their best rides, tell lies, exchange knowledge, reenact their moves, and, as we shall see, make music. Therefore, the place of musicking is a place of removal, away from the place of surfing itself. Connections between surfing and musicking must always be tenuous, changing, fluid.

SURFING AND MUSIC: APPROACHES TAKEN IN THIS BOOK

A key ethnomusicological tenet is that musicality is an integral part of group imagination and invention. Though the affinity group surfers is fluid and as fickle as the surf during a rapidly changing tide, its individual members do share the core experience of riding waves. Water may be the universal solvent, but it also binds us all. In my look at the musical practices of surfers in locations around the world, I keep returning to this shared experience that binds surfers. And where I may theorize the global, I also keep it real by grounding my interpretation in the real-life stories of individual members of this community. This book presents a series of case studies that explore different ways that surfers—and sometimes nonsurfers—associate the cultural practices of surfing and musicking. Along the way, I also hope to expand ethnomusicological thinking about the many ways musical practices may be integral to human socializing, and perhaps to being human in the first place.

The first three chapters are historical and move chronologically, with some overlap. I start with the earliest known music associated with surfing—Hawaiian chant—and continue through Hawaiian popular music during the first half of the twentieth century. I then move to the named genre Surf Music. Third, I analyze the music used in surf movies to see what they can tell us about surfing and musicking from the mid–twentieth century to the present.

Chapter 1, “Trouble in Paradise: The History and Reinvention of Surfing,” considers the origins of surfing and music about surfing in Hawaiʻi. The passage of time does not enable me to speak directly with pre-revival-era surfers, so I rely on Hawaiian legends and myths, early written accounts of surfing (most by Europeans and North Americans, but some by Hawaiians), and, most significantly for my work, Hawaiian mele (chants). A number of mele about surfing from the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries are the earliest examples of surfing music. Through these voices from the past, we see that surfing was ubiquitous in pre-revival Hawaiian society, practiced by women and men, girls and boys, and though we know more about royal surfers since it is their surfing mele that survive, we also know that common folk surfed, too. Thus it is not surprising that there were chants and dances, rituals, and even temples associated with surfing in Hawaiʻi.

Popular Hawaiian songs from the first half of the twentieth century reveal a changing role for surfing, especially as tourists began to visit Hawaiʻi and to learn to surf themselves. Surfing spread from Hawaiʻi to the rest of the coastal world, and at least during the first half of the twentieth century, emerging surfing affinity groups tended to look to Hawaiʻi for appropriate cultural practices, such as music and dance, to express community. Hula (dance or visual poetry) and hapa haole (half-foreign) songs from Hawaiʻi were and still are practiced by surfers on California’s beaches, for example. Yet surfing also changed as more and more people traveled to Hawaiʻi, and as surfing was exported from the islands. The first stop for globalizing surfing was California, and I show how the interaction between Hawaiʻi and California led to the reinvention of surfing in the twentieth century. No longer the ubiquitous cultural practice of pre-revival Hawaiʻi, what I call New Surfing became hypermasculine, and would be increasingly driven by commercial interests.

Chapter 2, “ ‘Surf Music’ and the California Surfing Boom: New Surfing Gets a New Sound,” picks up the story in California. Most conversations that pair the words surf and music are focused on two related genres of music that came to be called Surf Music: instrumental rock à la Dick Dale and the Del-Tones, and songs about surfing à la the Beach Boys. Both genres emerged in the early 1960s, and they do capture something of the history of surfing, especially in California at that time. What Surf Music captures is the mass popularization of surfing that resulted from new technologies of mass-producing lighter boards, not unlike the mass production of electric guitars by Fender, a Southern California company that became the preferred brand of surf rock bands. Surf Music encouraged the global spread of surfing itself and engendered enduring myths about Southern California and a newly white, youthful, and masculine surfing lifestyle. However, naming a popular genre of music surf was a problem for some surfers at the time, and became a problem for many who desired to make music about surfing subsequently. This second issue has only recently been resolved with the popularity of a number of surfing musicians.

If music on the beaches of Hawaiʻi and Southern California is a good index of surfing trends in the first half of the twentieth century, the music used for surf movies is an even better index for the second half of that century. In chapter 3, “Music in Surf Movies,” I survey the music used in a selection of surf movies that were particularly influential in shaping the musical practices of significant groups of surfers. I begin in the 1950s with the first surf movies for which we have the original musical soundtracks and then move through the formative boom years of the 1960s, to the VHS era, and then on to the present-day digital formats. With these movies I show what music was popular among at least some surfers before the named genre Surf Music existed, how some surfers responded to that genre, and the musical directions surfers have taken since the 1960s. The music used in surfing movies illustrates some of the diversity of musicking among surfers, but it also reveals distinct trends. For example, I show that surf-movie production emerged out of New Surfing’s new cultural centers: California and Australia. Surf movies, made by surfers for surfers, were a powerful tool for spreading ideas about surfing culture, especially music, to a growing and globalizing number of surfers.

The next three chapters are focused on the present or near present, and draw from my ethnographic work with living surfing musicians. Chapter 4, “Two Festivals and Three Genres of Music,” is a comparative study of two festivals, one celebrating a genre of music and the other featuring a surfing contest with an attached music festival. Both festivals took place in the summer of 2009 in Europe, and each represented very different approaches to music and surfing. The first festival took place in Italy and centered on the named genre Surf Music. However, there I discovered that the musicians most engaged with surfing were not playing Surf Music but were covering Jack Johnson songs or writing new songs about surfing in a punk rock style. The second festival was in Newquay, “the capital of British surfing,” located 260 miles southwest of London on the wave-grabbing coast of the Cornish peninsula. The music at this festival, which started as a professional surfing contest, tended toward two poles described to me as “mellow and surfy” on the one hand and “heavy and punky” on the other. The two festivals nicely frame three broad genres or styles of music that have emerged as key to my project: Surf Music, punk rock, and generally acoustic singer-songwriter music favored by an influential group of prominent surfers.

Chapter 5, “The Pro Surfer Sings,” asks how it is that some of the most influential and competitive surfers have managed second careers as musicians. It may be, as some surfer-musicians have suggested, an extension of their efforts at expression. Whereas for many of us just catching and riding a wave is an accomplishment (perhaps similar to getting through a piano étude without too many mistakes), the truly skilled surfer is able to move beyond the mechanics of the sport and use the ocean as a canvas for expression. It may also be that, since at least the mid–twentieth century, there has been a myth that surfing is a musical sport—a myth that first led me to this project. This chapter shows that musicking can be an effective way for professional surfers to expand their personal brand. Clearly the surfing body is a desirable commodity in the entertainment industry, and has been since the original Beachboys—the Waikīkī Beachboys, from Waikīkī, Hawaiʻi—appeared in the first half of the twentieth century.

Chapter 6, “The Soul Surfer Sings,” returns to a persistent ideal introduced in chapter 3: the surfer who attaches great meaning to surfing before and beyond any professional opportunities it may offer. The category soul surfer does not exclude professional surfers or musicians, though I do attempt to balance the emphasis given to professional surfers and professional musicians in the previous chapter. Chapters 5 and 6 may appear to construct a dichotomy between the pro surfer and the soul surfer, but as with so many things core to surfing, the boundaries are fluid: all the action is in the liminal zone. Chapter 6 includes ethnographies of surfing musicians primarily from California and in Hawaiʻi. In these locations we find similar ideas about music and surfing, but some distinctions as well. Some Hawaiian surfers focus in their music on Hawaiian issues of significance to them personally. Some California soul surfers also sing about Hawaiʻi and reference ideas from Hawaiʻi. But I propose that the role Hawaiʻi plays in this musicking should be interpreted differently. Taken as a whole, the voices I present in this chapter find surfing profoundly meaningful, even necessary for the maintenance of their souls, and they express some of this through music.

The final chapter, chapter 7, “Playing Together and Solitary Play: Why Surfers Need Music,” draws some conclusions about surfing and music-making as interlinked human practices. Looking again at individuals and groups of surfers who play music together, I draw out two recurring themes: homologies (surfing and musicking can be viewed as the same phenomena or, at the very least, as analogous) and community sharing (musicking allows surfers to form community in ways that surfing alone does not). Key to both of these themes is the belief among some surfers that both musicking and surfing create similar affective feelings or experiences, and that music provides a venue for exploring those feelings and experiences. I conclude with a well-worn and well-worth-rehearsing ethnomusicological finding: musicking is vital in creating community.