Читать книгу Queer Clout - Timothy Stewart-Winter - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

_________

A Little World Within a World

“I MOVED TO my own place when I was eighteen, to a building near Clark and Division, which was the place to live if you were gay,” recalled John, a gay man, in 1983. The year to which he referred was 1950. The previous year, John’s priest had been shocked by his disclosure at confession that he had had a sexual encounter with another teenage boy. John added that once he moved to Chicago’s Near North Side, “When you applied for a job, you hesitated to give an address in that area. Quite often I gave my parents’ address to avoid remarks like ‘The queer North Side, eh?’ or ‘Is that near Clark and Perversion?’”1 Though Americans had long viewed cities as dens of iniquity, foreignness, and political radicalism, as whites began to move to the suburbs in the 1950s, sensational depictions on television and in movies cemented the cities’ reputation as dangerous. In novels and in newspapers, cops and G-men did battle to reclaim the urban jungle from dangerous criminals and sex fiends.

But cities were also places where blacks and gays could develop communities. African Americans left the Jim Crow South for Chicago in large numbers, with nearly half a million crowding into the South Side’s “black belt” by 1950. As the boundaries of the black belt threatened to burst into the surrounding white residential areas, violence flared, yet African Americans found the chance for better work and pay in Chicago than in the places they had left behind. Gay men and women also found work, friends, and ways of living that were impossible in the small towns or the provincial urban neighborhoods where they had grown up. When sexologist Alfred C. Kinsey first traveled from Indiana to Chicago in the summer of 1939 in search of homosexuals to interview for a possible research project, he found himself swept up in a dizzying array of parties, clubs, and bars, “which would be unbelievable if realized by the rest of the world,” he wrote to a colleague.2 Almost three decades later, one Chicago lesbian went so far as to lament how deeply involved younger lesbians seemed to become in the city’s queer communities: “[J]ust because they’re homosexual, the gay life becomes everything.”3 Many men and women were afraid to dip their toes into the gay world, but urban America offered many others access to a limited degree of freedom.

The most visible gathering places for gays and lesbians in 1950s Chicago were in the two main entertainment districts, north and south of downtown. On the South Side, just north of the historic black commercial center of Bronzeville and a block from the city’s first high-rise public-housing project, which opened in 1950, the jazz trumpeter “Tiny” Davis, known as the Female Satchmo, opened a jazz club with her partner Ruby Lucas. At Tiny and Ruby’s Gay Spot, later demolished to make room for the Dan Ryan Expressway in 1958, Davis recalled, “The daddies are daddies and the fems are fems.”4 At Big Lou’s, a Rush Street lounge on the mostly white Near North Side, a police officer in early 1952 reported “observation of effeminate men and mannish women in the place, males dancing with males, females dancing with females, and undue demonstrations of intimacy between women at the bar.”5 Between the two places, at the Town and Country Lounge in the basement of the Palmer House hotel in the central Loop commercial district, predominantly white gay men gathered for cocktails, often under the noses of straight hotel guests, and well-heeled men mingled with male window dressers and “ribbon clerks” working in downtown department stores.6

As gay enclaves developed, a small number of Chicagoans, mostly gay men but some notable women as well, launched tiny organizations aimed at improving the status of homosexuals. Chicagoans founded in 1954 the first chapter outside California of the Mattachine Society, the pioneering national “homophile” group in the postwar era, which advocated greater acceptance of gays and lesbians, their successful social and cultural “adjustment” in American society, and more sympathetic views of their lot on the part of experts. Homophile groups sought to improve the status of the homosexual in American society by holding discussion groups; meeting with sympathetic doctors, lawyers, pastors, and scholars; and publishing newsletters and magazines. The homophile movement also discussed the need to reform criminal laws against same-sex acts.

In many ways, the federal government drove the state repression of homosexuality in the quarter century after World War II. In the so-called lavender scare, officials investigated and purged gay and lesbian federal employees, beginning in 1950. That year, Senator Kenneth Wherry of Nebraska launched an investigation of gay employees in the State Department, sparking a wave of hostile press attention that coincided with the anticommunist panic in Washington and Hollywood. In a 1953 executive order, President Dwight Eisenhower excluded gays and lesbians from federal employment on the grounds that they constituted security risks, codifying the antigay purge that Congress had initiated. The suppression of urban vice increasingly intersected with Cold War politics and the expanding mission of federal law enforcement.

But antigay policing in the 1950s entailed more variation and unevenness than the lavender-scare framework alone can explain. The federal bureaucracy’s persecution of gays and lesbians became unrelenting and systematic. Local police departments across the country cracked down on gays and lesbians as well, in many cities more aggressively than in the interwar period. In the words of one gay man, however, queer life in Chicago in the years after World War II felt like “a regular wavelike pattern of freedom for homosexuals and then a period of crackdown.”7 There, politicians viewed the presence of establishments catering to gays and lesbians—especially on the North Side, where they were situated near predominantly white tourist and convention areas—as a law-enforcement and public-relations problem. Under pressure from politicians to crack down on vice, municipal police and officers of the county sheriff conducted raids on gay spots, humiliating the patrons by distributing the names of those arrested to newspapers for publication. This occurred often enough that patrons calculated the likelihood of such raids in weighing how closely to associate with other gay people. The police who launched Chicago’s antigay crackdowns had typically faced demands to do so from muckraking reporters and elite reformers, especially the Chicago Crime Commission, an offshoot of the Chicago Association of Commerce and Industry. To these business-led reformers, homosexuality was to be regulated as a form of illicit vice. Not only were the operators of a gay bar potentially subject to criminal penalties in much the same manner as sex workers, pornographers, gamblers, and abortion providers, but so were the patrons. Law-enforcement agencies ensnared gay Chicagoans in small but growing numbers.

The emergence of the homophile movement in the 1950s was deeply shaped by local law enforcement. Situating homophile activism in the context of urban politics reveals two important points about the midcentury politics of sexuality. First, the tiny gay movement that arose in the course of the decade was shaped by the necessity of concealment. The figure of “the pervert” increasingly populated America’s big-city newspapers, appearing abstractly as a threat to the social order or concretely as a result of being exposed and then, usually, terminated from employment. Joining the homophile movement required overcoming the fear of being blackmailed, robbed, or—above all, and most universally—simply being exposed as gay, even to relatives or friends. Pearl Hart, a lawyer who advised homophile activists in postwar Chicago, was also experienced in defending other clients—those charged as communists or prostitutes, for example—who similarly faced stigma and pressure to conceal their deviation from the American mainstream. Second, the gay world was defined as deviant because gay sex was removed from the domestic, procreative, marital relations of proper breadwinners and their families. Gay people commonly believed that politicians most often cracked down on gay life during election campaigns, appealing to voters who were assumed to consist of such families. But for many of their patrons, queer bars were crucial sources of comfort and conviviality. “When you walked through that door,” recalled Esther Newton, who later published an ethnographic study of female impersonators based on her University of Chicago dissertation, “it was like you dropped through a trap door into this other world.”8 Gay bars and nightclubs served as an insecure haven from the rest of the city. Women, even more than men, frequently gathered at house parties. One woman recalled her friends carrying their party clothes, lest they attract hostile attention on the streets: “When we got to the party we’d take off the skirts, put on the pants, and have a party, and before we’d go home we’d take off our pants, put on our skirts, and bundle up the pants and go home.”9 Those who deviated from the postwar sex and gender order, no less than from its conformist political orthodoxy, were forced underground.

The gay subcultures of America’s largest cities mirrored the self-consciously rough-and-tumble spirit of postwar big-city life. In Unlike Others, a pulp paperback novel published in 1963 and set in Chicago, Valerie Taylor captured in brilliant detail how deeply gay life was embedded in—yet marginal to—local politics. Taylor’s protagonist, Jo, spends her days working in a downtown office tower as the underpaid assistant to the womanizing male editor of a corporation’s in-house employee newsletter. Meticulously concealing her private life from her boss, she finds her way into the city’s lesbian subculture after hours. At one point, Jo is awakened in the middle of the night by a phone call from her best friend Richard, a gay man who has been arrested in a bar raid. “Knowing the percentages,” Taylor’s narrator observed, “you never betrayed anyone. If you had straight friends who knew what you were and accepted you just the same, without any reservations—[Jo] never had, but some of the boys claimed it was possible—you never gave anyone away to them. It was a little world within a world.”10 Friends and lovers thus faced the risk of becoming enmeshed in the dangerous clutches of policemen, with money and influence offering the only means of escape.

The predicament of Jo and her friends offered a vivid metaphor for the status of gays and lesbians in the public sphere of America’s second-largest city. Gayness, spying, and concealment were powerfully linked together in popular culture of the era. Gay people may have been “deviates,” but if Taylor was right that their subculture prized “loyalty” so highly, that feature aligned them—rather ironically—with the mainstream American preoccupation in the Eisenhower years with questions of loyalty and disloyalty, even if their allegiances took an improper object. Public disapproval was forceful. Nonetheless, one gay male Chicagoan recalled, “the umbrella was still protecting us, of ignorance. I mean, not many people knew about homosexuality.”11

“They Carry on like ‘Father Time’”

During the Great Depression and World War II, queer life was more visible in Bronzeville, the bright-light district on the African American South Side, than anywhere else in Chicago. Though politically subordinate to white police and property owners, Bronzeville offered perhaps the nation’s richest and densest concentration of black culture and commerce.12 Since the early twentieth century, when the black-owned Chicago Defender, one of the most prominent black newspapers in the nation, exhorted its many Southern readers to come north in search of freedom, white politicians had allowed prostitution, gambling, and gay entertainment to flourish in black neighborhoods.13 “As in all Northern cities, the lowest of the races get together,” wrote the authors of a 1950 guidebook to the city’s nightlife. “This is most common among the degenerates in the twilight zones of sex. They meet everywhere, but their principal point of congregation is around Drexel Avenue and 39th Street,” an intersection in the heart of Bronzeville’s entertainment district.14 For example, the multiracial Finnie’s Halloween Ball, an intensely competitive contest in female impersonation, was covered extensively in the early 1950s in Ebony and Jet, African American magazines produced by Chicago’s Johnson Publications and distributed nationwide. Glamorously dressed female impersonators competed for prizes. “More than 1,500 spectators milled around outside Chicago’s Pershing Ballroom,” said a 1953 article in Ebony, describing one such drag ball, “to get a glimpse of the bejeweled impersonators who arrived in limousines, taxis, Fords and even by streetcar.”15 Black queer life was thus visibly woven into the public culture of the black South Side.

For black Chicagoans in the 1950s, the daily risk of encountering police harassment did not depend on one’s sexual inclinations. Life in the slums of the postwar urban North, and later in its segregated housing projects, was controlled by a police force drawn from all-white blue-collar neighborhoods. African Americans were accustomed to police brutality, and they had had little success in challenging it in the face of a dominant culture that held the police in high esteem. What little progress black activists made against police brutality in the 1950s occurred in the courts. Although the city’s mainstream newspapers often ignored crime in black neighborhoods, in the second half of the 1950s the African American press increasingly covered the brutal treatment of black citizens by white officers, even in the citizens’ own homes. The Defender had drawn attention to police brutality on the South Side in a high-profile series of articles in 1958. That year, for example, thirteen Chicago police officers broke into James Monroe’s house in the middle of the night based on a false tip in a murder investigation; woke him and his wife with flashlights; and struck, pushed, and kicked him and his six children. In a landmark ruling, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Monroe could sue the involved officers for civil damages under a federal statute originally meant to suppress the Ku Klux Klan in the post–Civil War South.16 Nevertheless, on the city’s South Side, police harassment remained a fact of life. Not until the second half of 1963 did a sustained campaign of protest against police brutality in Chicago’s black neighborhoods begin to take shape.

For white gays and lesbians, police harassment increasingly constituted their most important point of contact with the state. African Americans in Chicago in the 1950s faced police harassment regardless of whether they were queer, and in this sense being gay made less of a difference for blacks than for whites—that is, it did not separate a black gay person as much from his or her black peers as it did a white gay person from his or her white peers. White gays and lesbians faced capricious punishment by the criminal-justice system more often than other whites did. Gay men were most often targeted for physical touching, for dancing, or for propositioning undercover officers; lesbians were most likely to be arrested in bar raids for violating sartorial laws—that is, for wearing men’s clothing.

To have one’s name printed in the newspaper following a police raid was the quintessential punishment for being gay. In America’s postwar antigay witch hunts, the fact that “such a charge will probably be dismissed the following morning” did not alter the fact that “there is a name spread on a record that will not be lost” and that ultimately “the whole of this very common procedure will surely spell ‘pervert’ in blazing letters for anyone who cares to take the trouble.”17 Exposure as a homosexual—especially through an arrest—jeopardized one’s ties to friends and family and, especially, to one’s job. Having a good job, if you were gay, meant rigorously concealing your gay life, even from family members. For example, a working-class Chicago woman recalled that her first sexual experience took place around 1954, when she was seventeen years old. “I think we were in a car,” she recalled. Soon afterward, she and her new girlfriend “started going to the bars in Chicago quite a bit,” even though she still lived with her parents at home at the time. Thirteen years later, she had never discussed being gay with her parents. “I don’t see how they could not know it,” she remarked, “but nothing has ever been said.”18

Police raids, portrayed in the press as a necessary means of protecting the city from “hoodlums,” reflected the linkage of gay life with criminality and the underworld. In Chicago, as in other large cities, organized crime syndicates wielded great power over gay nightlife because they possessed the means to buy protection by corrupting the police. Mob profiteering from cover charges, high prices, and diluted drinks provided funds for such protection. “It didn’t make us angry because it allowed us to be somewhere,” recalled Jim Darby, a patron of gay bars in Chicago in the 1950s. The police by contrast seemed only to make life dangerous. Gays and lesbians knew they could not expect authorities to treat antigay violence, extortion, and blackmail as serious crimes. Darby, for example, was on leave from the Navy, drinking in Sam’s, one of the North Side’s busiest gay bars, when it was raided in 1952. “I knew I was drunk already,” he recalled, “and I remember the jailer banging on his desk with his club, yelling, ‘God damn you fuckin’ queers, shut up and go to sleep!’” He recalls that, in sentencing him to a fine, the judge said it was a sad comment on the nation’s military that a sailor would frequent such a place.19

Postwar American anxieties took the form of worries not only about communist subversion but also about crime. The perceptual link between crime and cities was tightened by a series of lurid congressional hearings on organized crime in 1950 and 1951, the first such hearings to receive a large national television audience. Chicago then remained strongly associated in the public mind with Al Capone, John Dillinger, and other legendary criminals of the Prohibition era; indeed, Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee, who presided over the hearings, declared Chicago “perhaps the one most important center of criminal activities.”20 Millions of Americans heard shocking testimony, which propagated the perception that big-city municipal governments were in fact still captive to the shadowy crime syndicates that had flourished during Prohibition.21 The Kefauver hearings stoked a lasting preoccupation on the part of the news media with what one historian called the “notion of a vast, hydra-headed crime syndicate,” and with Mafia infiltration of politics and business.22 The hearings also proved a boon to the politicians involved in sponsoring them.

In this context, police scrutiny of gay life intensified in the first half of 1952, amid suggestions that Chicago was on the verge of returning to the lawlessness of the Prohibition era. In January of that year, Chicagoans learned that for two years they had been consuming millions of pounds of horse meat, disguised as ground beef, apparently as the result of mob profiteering.23 In February, the acting Republican committeeman of the 31st Ward, known as an enemy of the so-called “West Side Bloc” of mob-linked politicians, was shot and killed; his murder was never solved.24 A group of business-led civic reformers formed a Committee of Nineteen to investigate corruption. Austin L. Wyman, the chairman of the Chicago Crime Commission, charged that both Democrats and Republicans tolerated gangsters in their ranks locally. “Why have there been so few prosecutions of big-time hoodlums?” he asked U.S. Attorney Otto Kerner.25

The city’s business-oriented, Anglo-Saxon Protestant elite, through the Crime Commission, hired investigators to examine gay nightlife, gambling, and female prostitution. The revelations turned into a full-blown quest to identify scapegoats and clean up a city portrayed as corrupt and decaying. City officials sought advice from other cities about how best to eliminate crime and associated ills. For example, in 1953, a Washington correspondent for the Chicago Daily News sent his editor suggestions about how to intensify the public’s demand that the city be cleaned up. “It might be worth exploring,” he wrote, “whether the Miami Herald could suggest people, out of their cleanup experience there; the California Crime Commission, which the Kefauver committee showed was somewhat on the ball, could be helpful.” In advocating for the police to crack down on deviant behavior, Chicago journalists cited the experience of Miami and of cities in California as exemplary. Miami had passed a pioneering ordinance prohibiting female impersonator performances in 1952, and California state officials had established their state government as the leading edge of the nation’s postwar antigay crackdown.26 Those lobbying for a crackdown on gay life in Chicago thus turned to counterparts in other large cities for advice and assistance, just as homophile activists would do, later, in 1954, when they first formed a Chicago chapter of the California-based Mattachine Society.

Hoping to preempt calls for an independent civilian investigator, Mayor Martin Kennelly appointed nine aldermen to an “emergency crime committee”—known as the Big Nine—to investigate organized crime in Chicago. The crime committee hired a former Pittsburgh police detective, Robert Butzler, and heard his testimony about his investigation of “conditions” in the 35th Police District on the Near North Side. Butzler appears to have focused his investigation of gay life on a bar called Big Lou’s. “Approximately half the persons in this tavern were perverts, this being evident from their lewd suggestive conversation and actions,” wrote an investigator, likely Butzler, in December 1952. “Other patrons observed in the booth and at the bar while dancing in the place were also very lewd in their conduct.”27 The following month, the same investigator noted that “the place continues to be a pervert hangout to both sexes but more emphasis being upon the lesbians. From the conduct of the female patrons,” he concluded, “it was very evident they were lesbians and their lovers.”28 On January 26, the owner of Big Lou’s, Lucille Kinovsky, was arrested in a police raid, along with three patrons.

A police raid on a gay establishment was at once a law enforcement action and a scripted ritual of exposure: a public event and a private crisis. Butzler’s testimony electrified the local press with his reports of gambling, prostitution, and elusive agents of organized crime families; in the words of the Tribune, he threw a “spotlight” on “a segment of Chicago and a cast of characters as strange and colorful as anything ever dreamed up for a Hollywood movie.”29 Butzler also testified that one club, the Hollywood Bowl, was “full of male degenerates. They were sitting close and holding hands.”30 But the Big Lou’s raid also reverberated through the social and domestic lives of those implicated. Lucille Kinovsky had grown up on the West Side of Chicago, the daughter of working-class immigrants from Bohemia. Her nephew, John Vandermeer, remembers her as an overweight, butch woman who played softball and had matching wedding rings with her partner Bernice. The nature of their relationship was never discussed, but Lou brought Bernice to family dinners on the West Side. Though family members did not speak of her explicitly as being a gay person, Lou was accepted—and even treated as one of the guys by Vandermeer’s father and uncles: “When she would be at one of the family get-togethers, it would be her and the men off playing pinochle, and the women would be off in the kitchen.” Kinovsky even hired Vandermeer’s father to work for her: “She was looking for a bartender and he was looking for a job, and so he tended bar.”31

Even queers who had clout under this regime, then, were nonetheless highly vulnerable. Kinovsky had her business destroyed by the Big Nine. Called to testify before the emergency crime committee, “Miss Kinovsky denied that her tavern at 731 North av. is a resort for perverts, both men and women.” She acknowledged, however, that it had been raided twice in two years by police.32 In April, she was found guilty of being the keeper of a disorderly house, fined $200, and, unable to pay the fine, was sent to Bridewell (the municipal House of Correction) to “work out the fine.”33“What they got her on was paying off the police,” Vandermeer recalled, “which she claimed to me personally—I remember this vividly—she claimed she never, ever did. But that’s what they got her on.” Vandermeer’s youthful understanding was that his aunt had been “run out of town.” After she was charged and convicted, she moved to Baltimore.34

Throughout the summer and fall of 1953, the Crime Commission hired more investigators and sent them to visit other gay establishments. The commission had two means of getting its way, partly by playing the police and the press off one another. First, “conditions” in a particular establishment would be reported to police in order to generate repressive action. Often, such direct requests for police raids were effective. One record shows, for example, “C.C.C. wrote letter to Commr. Of Police, June 2, 1953 advising that Lake Shore Lounge, 935 Rush Street was a pervert joint so packed that it was impossible to get to the bar or move around. Language filthy and obscene. Tribune June 6, 1953 stated 42 men were arrested at Lake Shore Lounge 935 Rush St.”35 According to the commission’s executive director, if law enforcement did not respond, the next step was to leak stories about these conditions to the reporters.36

Raids did not always lead to the closure of the establishments where they took place, however—something that would change in the 1960s. In the 1950s, Chicago’s police force lacked the administrative means to revoke a gay bar’s liquor license after conducting a raid. In a fall of 1953 report on two gay bars, for example, an official of the Chicago Crime Commission noted his exasperation with downtown police district commanders: “We have already written reams of material on the Shoreline which has for years been a homo-sexual hangout and the Hague is the same type establishment.” And yet, he reported, “though both have been subject of several police investigations and raids[,] they carry on like ‘Father Time.’”37 City officials had limited powers to keep a licensed establishment closed. The appeal commissions established by the state’s 1934 liquor control law often reversed local officials’ decision to revoke a tavern’s liquor license.38

Political connections and graft could enable a gay bar owner with sufficient clout to keep his place open over a relatively extended period. One bar owner, Chuck Renslow, who had operated a physique photography studio that also exposed him to police and post office harassment, recalled aspects of running a gay bar in this period with something akin to nostalgia: “The Gold Coast had a 2 o’clock license, which means that we had to close at 2 [or at 3 on Saturday nights]. One year, it was a Wednesday, and in the middle of the week it was New Year’s Eve. And the bar was packed! I called up the station and said, ‘We got a big business, how long can I stay open?’ He says, ‘Fifty dollars an hour, be sure you’re closed by 6 when people go to work.’ That doesn’t happen today.”39 Renslow drew the conclusion that, as much as payoffs and raiding posed serious problems for bar owners, they also occasionally provided certain advantages not available under today’s reformed regime of liquor regulation. He recounted one evening when his downtown bar, the Gold Coast, was raided—but “they shouldn’t have raided it, ’cause we were paying off. So I went to the station, and I said, ‘Hey, why’d you raid?’ and he says, ‘Oh, my God, we made a mistake! Why didn’t you tell the guys not to be in there?’”40 Many bars catering to queers enjoyed relative security from police harassment only at the price of Mafia control of their operations, or graft payments to police officers or politicians. This type of freedom was a precarious one indeed.

“A City of Family Men”

Chicago’s Democratic machine had bridged divisions of space and class in the decades after it was forged in the 1920s and cemented by the New Deal. In the aftermath of World War I, Mayor Anton Cermak united white Chicagoans, especially immigrant groups, into a powerful multiethnic coalition that survived his assassination in 1933. Politicians accepted and even celebrated some differences of nationality among whites—that is, among Irish, Poles, and Germans. Blacks were part of the machine, yet they had a distinctly subordinate political status. In the years after World War II, white ethnic neighborhood boundaries gave way to stark black-white divisions, as the city became increasingly segregated. The large swath of the South Side that Richard Wright called “an undissolved lump in the city’s melting pot” was overcrowded already at the close of the war and continued to swell in the 1950s.41 Chicago’s “black metropolis,” as St. Clair Drake and Horace Cayton called it in their famous sociological study published in 1945, was policed almost exclusively by white police officers. Time and again in the 1950s, when blacks moved beyond the edges of the ghetto, whites rioted. Black Chicagoans paid inflated prices for inferior housing and goods, and even middle-class blacks could find housing only on financially exploitative terms. Outside the South Side, police tolerated white violence against African Americans who tried to move into white neighborhoods.42

In the post–World War II era, Chicago politics involved a constant, always imbalanced struggle between the machine and good-government reformers. Commentators increasingly spoke of “reform” and “machine” Democrats, even though these were not neatly separable camps.43 Except for a few diehard “goo-goos” who wielded little power, nearly all Chicago politicians accepted that the lifeblood of urban governance was the exchange of patronage for votes.44 Most, too, at various moments in their political careers, found it advantageous to advocate reforms or to wrap themselves in reform’s mantle. Precisely to tamp down the perception that his election in 1955 meant a triumph of machine patronage, for example, Daley quickly centralized the former aldermanic control over driveway permits—an especially lucrative form of graft—and other favors that city council members could do for their constituents.45 Tacking back and forth between the politics of the machine and of reform was a well-worn path to success.

In Chicago at midcentury, the New Deal coalition embodied the aspirations of sons and daughters of the Depression for material prosperity, combined with the expectation for men to labor remuneratively outside the home and women to labor inside the home to create a comfortable home and rear children. Ordinary men in the 1950s wanted and were expected to become family men. A young man from a middle-class, predominantly white North Side neighborhood wrote that at his age, “Most Lake View guys are married, have a few kids, know a good trade and have a car.”46 A few miles to the west, social-service workers who engaged with poor and working-class young black and Latino men were making similar observations: “It is okay to remain single until around age twenty-eight, but if you have not married and settled down by that time, the male is considered ‘queer.’”47 Women were expected to marry at an even younger age.

Gays and lesbians in postwar America lived at least partly outside this framework, which the historian Robert Self has labeled “breadwinner liberalism.”48 At once provincial and self-consciously modern, the powerful men who ran Chicago’s political machine embraced a welfare state whose provisions were as generous as they were narrowly premised on a white, straight, nuclear-family formation. The high tide of Daley’s mayoral administration coincided with the peak of breadwinner liberalism’s status in American politics. Advertisements for his first campaign, in 1955, featured his wife and seven children; “Let’s elect a Family Man to represent the families of Chicago,” said one.”49 For Daley, a spotlight on his large family helped focus media coverage on his blue-collar Irish Catholic parish life, rather than his ties to downtown business interests or his connections to men with syndicate ties. “Smoke filled room?” asked the caption of a photo of the Daleys at the breakfast table in one print advertisement for his campaign. “Yes, filled with the smoke of bacon and eggs frying in the pan.”50 Upon his sudden death during his sixth term in office, in 1976, the Chicago Tribune obituary said, “He prided himself on being a ‘family man’ in a city of family men.”51

In this context of machine politics, family ties held together households, but also wards, neighborhoods, and political relationships. Alderman Vito Marzullo, one of Daley’s closest allies on the city council, later described his loyalty to the mayor in terms that illustrate how deeply heterosexuality was built into local political culture: “He’s a great family man…. I got six married children. He came to every one of their weddings. He invited me to the weddings of every one of his kids. You don’t go back on people like that.” Heterosexual marriages were also interlaced with the dynamics of patronage hiring, thus helping form the glue of the local political culture.52

Daley was elected in 1955 partly because black voters rebelled against a reform mayor who seemed to crack down only on policy gambling and jitney cabs in their areas while leaving white criminal entrepreneurs untouched. Kennelly, the city’s mayor at the time of the Kefauver hearings, had been slated by the Democratic machine in 1947 as a “reformer,” to replace Edward J. Kelly, who had consolidated Cermak’s party organization since Cermak’s death in 1933.53 Testifying during the Kefauver hearings, Kennelly awkwardly defended the city. The episode increased the pressure on him to crack down on corruption and syndicate businesses, and he responded by cracking down on the illegal policy-gambling racket in black neighborhoods, as well as the illicit, unregulated jitney-cab regime there.54 This crackdown, in turn, displeased black voters, who had been only recently converted to vote Democratic in local elections. In the process, Kennelly garnered the public enmity of U.S. Representative William L. Dawson, boss of the black “submachine,” as well as the antipathy of many Italian and other white-ethnic voters in the city’s poor, machine-dominated “river wards.” Many working-class white voters, too, were more loyal to their machine precinct captains than to the mayor’s downtown allies, and they had little interest in Kennelly’s drive against illegal gambling.

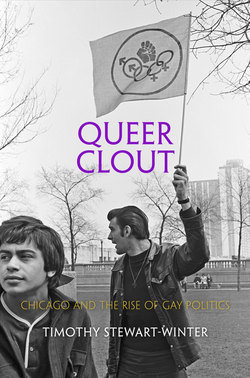

By December 1954, Kennelly seemed so weak that the machine ousted him from the ballot, slating Richard J. Daley to run as the machine’s candidate. The bitter, expensive primary contest that followed was the first local race featuring television commercials. Though a Catholic himself, Kennelly’s strongest backers were the Protestant business elite. In a city with one of the most densely concentrated Catholic populations in the country, Daley, the ward heeler who had served for two years as chairman of the Cook County Democratic Organization, benefited from the perception of Kennelly as elitist and out of touch.55 Indeed, the Chicago Tribune had long taunted Kennelly for his failure to marry, and his opponent exploited the opening.56 Daley’s children were featured in campaign materials labeled “A Family Man for a Family City” (see Figure 1).57 The Tribune had reported on Daley’s “happy family life with his wife … and their seven children” just before his primary win.58

FIGURE 1. Primary campaign placard for Richard J. Daley, February 1955. Courtesy of Chicago History Museum.

In the equally hard-fought 1955 general election for mayor that followed, organized crime—with its corollary, vice—was a central issue. Daley’s Republican general-election opponent, Robert Merriam, charged that Daley would end Kennelly’s crackdown on policy gambling, and the city would become “wide open.” He quoted Variety as saying that “strip tease joints have started to reopen in anticipation of a Daley victory and wide open conditions,” according to one journalist.59 In a veiled reference to Daley’s evident willingness to tolerate policy gambling in black neighborhoods, Merriam charged, “There’s no such thing as limiting the evils of a wide open city to one section.”60 Faced with these charges, Daley claimed he would wage “an all-out war on crime in every form” to make “our neighborhood streets safe for women and children” and to ensure that “the syndicate will be driven out of Chicago.”61 Daley’s election as mayor made him unusually powerful because he had served as chairman of the Cook County party organization, a post he continued to hold as mayor. Moving rapidly, he centralized control of the city he would govern for two decades. Ominously for gays and lesbians, however, Daley had campaigned on a promise to fight crime and protect women and children—and the pressure for more aggressive policing would soon escalate.

“To Round Up Sex Deviates Is the Best Procedure”

Bar raids were accompanied by another, more complex but equally pernicious form of police harassment. Chicago’s four daily newspapers, which competed for a readership increasingly dominated by young parents, devoted sensational coverage to violent sexual crimes against children, in a society notably obsessed with families, children, and child rearing, and at a time when men and women married at younger ages than ever before or since. Experts in psychiatry and criminology fielded questions from journalists and offered authoritative comments about sexual degenerates, sexual psychopaths, and sex fiends, as well as the broader and more loosely defined category of deviates, conflating consensual and forced acts.62

The occasion for Chicago’s worst such panic was a triple murder in the fall of 1955. Three teenage boys disappeared and their bodies were soon found abandoned in a wooded area in a forest preserve on the city’s northwestern outskirts. Police began combing the areas near where the bodies were found, as well as areas that had been condemned by eminent domain for the construction of the Northwest (later Kennedy) Expressway. Newspapers repeatedly speculated on several possible theories—was it a teenage gang or a crazed sex degenerate?—that implicated bowling alleys, schools, movie theaters, and bars as potential sites of abduction. A psychiatrist who worked frequently with the criminal courts quickly declared they “were killed by a member of Chicago’s colony of sex degenerates,” even though the autopsy “disclosed no signs of sexual molestation.” This expert publicly called on police to “round up every known sex offender and moron,” further advising police that “there are several Chicago areas where persons with abnormal sex attitudes tend to congregate.”63

The extremely brutal nature of this crime (the Schuessler-Peterson murders), the lack of solid leads, and the dispersion of potential clues across the disparate landscape of the North Side all helped to unleash the imaginations of millions. The boys’ bodies were found naked, strangled, and mutilated, not far from horse stables.64 In the absence of leads, police sought out “sex degenerates,” who, one representative expert told a reporter, “often seek their prey in movie theaters.” Journalists reported that some of the county forest preserves had long “been frequented by sex degenerates.” Perhaps, one expert suggested, the killer could be found if his “previous sex deviations” happened to be already “known to police.” Within just a few days, city and sheriff’s police were “rounding up persons whose recent actions indicated sex degeneracy or sadism.”65 Police combed through lists of paroled sex offenders, interviewed more than 300 “sex deviates” in six months, and several times released the names of suspects who were later dropped from the inquiry. In one case, police released a suspect’s name with the “incriminating” fact that he had on his person, at the time of his arrest, a business card from a “gathering place for sexual degenerates.”66

Gay men were not the only ones the police questioned—at one point, the employees of eighteen Northwest Side packing plants were interviewed—but gay men were the group to which the police kept circling back.67 One columnist claimed that, according to “a friend of mine who is an experienced and successful policeman,” it is best “to round up sex deviates” and that “in a high percentage of cases, this procedure leads to the discovery of the murderer.” This, of course, implied that harsher punishment of those showing signs of “deviation” could have prevented the crime.68 Ordinary Chicagoans, too, demanded that city elders “place under constant surveillance or remove completely from society all known and suspected sex offenders.”69

The city’s obsession with the Schuessler-Peterson murders sheds light on how race and class determined the political meanings of violence against children. Daley frequently repeated an offer of a $10,000 reward to anyone who helped solve the triple murder. After the Schuessler boys’ father died of a heart attack several weeks later, Daley even proposed that the city provide “some program of aid” to the grieving widow. It is instructive to compare Daley’s response to the triple murder with his handling of the case of another young Chicagoan slain in a widely publicized murder during Daley’s first year as mayor. Daley proposed no reward in the murder of Emmett Till, the fourteen-year-old Chicagoan killed two months earlier—albeit in Mississippi—in the twentieth century’s best-known lynching, and no municipal outlay to support his mother, the grieving Mamie Till Bradley, though she, too, was a single mother. (Daley did wire President Dwight Eisenhower, asking the federal government to become involved in the investigation.70) At least one letter published in the black-owned Chicago Defender invoked both crimes in a broad indictment of society’s treatment of children; Mrs. Bradley, the newspaper reported, sent her condolences to the mothers of the three murdered white boys.71

The perception of gays as predators profoundly shaped the response of law enforcement to crimes against children. This fact has been airbrushed out of accounts of the Schuessler-Peterson case, which was for decades among the nation’s best-known unsolved murders. Even the best book written about the murders, which was written from a law-enforcement perspective but generally avoids sensationalism, misrepresents profoundly the reasons for the investigation’s focus on gay men. “Single men living unconventional lifestyles and other persons unable to make a good accounting of their whereabouts on the nights in question fell under suspicion,” the authors acknowledge. But they portray police harassment of gays and lesbians in a more benign light than the evidence warrants: “A rumor that gained currency among the cops and reporters was that the slain boys and their schoolyard chums were in the habit of extorting money from known homosexuals—demanding cash in return for silence. For this reason, investigators took a hard look at the gay community.”72 In fact, however, gay men were targeted for investigation not only—indeed, not primarily—because they were victims of blackmail but rather because they were seen as possible predators.

These investigations could destroy careers quietly even if no charges were ever filed. One of those questioned and forced by the Chicago police to take a lie-detector test was Samuel Steward, a writer and English professor at DePaul University, a Catholic university on the North Side. In March 1956, Chicago police interviewed Steward at his home and then brought him to a police station to answer questions about his whereabouts the night of the murders. In order to give an alibi, he had had to explain that he was an English professor at DePaul University. Though he passed the lie-detector test, he wrote in his journal that day, “If word of this gets to DePaul … it would definitely end me there.” Steward later said in an interview that he was cleared of the murders “largely because I had no car” and did not know how to drive, and thus could not have dumped the bodies in the forest preserve. By the end of the same week, however, he had been called in to meet with the dean of the school and was told his contract would not be renewed. “I tried to get him to say why,” Steward wrote in his diary, “but all I could force out of him was ‘Shall we say for outside activities?’”73 Steward’s firing illustrates how easy it was for employers to accede to the pressure of press and police for the persecution of innocent gay citizens in the wake of a sex-crime panic. The lucky ones were those eased out of a job quietly.

Because the sex-crime panics normalized the idea that gay people did not enjoy ordinary procedural rights, the repeated investigations fostered a climate of fear. In December 1956, the disappearance of two young sisters, Barbara and Patricia Grimes, who had also gone to the movies, and the discovery of their bodies a month later, evoked a similar panic. “Chicago seems to have gone quite off its rocker about the Grimes case,” wrote one gay man that spring, describing its impact on gay men sought by the police.74 In July 1957 it was reported that a “limping blond youth” had been seen with Robert Peterson by the eye doctor who cared for his younger sister; dozens of citizens called and wrote the police with tips.75

In late 1959, eight detectives within the Chicago police department’s sex bureau were still assigned full time to the Schuessler-Peterson investigation.76 By the fifth anniversary of the murders, in the fall of 1960, the Tribune reported that 44,000 people had been interviewed and 6,500 reports and complaints investigated. Of 3,500 suspects questioned, 45 were indicted, and 40 convicted of various crimes, including crimes connected to “perversion.”77 Nearly two years later, a national gay magazine reported that the case “has led to continued police harassment of homosexuals (as alleged suspects) throughout the Midwest.” And new suspects were still being rounded up.78 It is difficult to overstate how powerfully the media-generated sex-crime panics of the 1950s—and the Schuessler-Peterson murder investigation in particular—struck fear into gay men.

Although the black press did not call for police crackdowns on deviates in the manner of the white-owned daily papers, black middle-class respectability politics increasingly shaped the coverage of queer life in the black media. The drag balls that had been a staple of Ebony and Jet received noticeably less coverage by the late 1950s, and as civil rights activism became more prominently featured, queer culture was less often portrayed in favorable ways. A Defender reader complained, “I saw in your paper some months ago some men dressed as women. Please don’t advertise the mess.”79 In 1960, a black reformer complained that “there seems to be almost a tacit acceptance that certain conditions can and will be tolerated in a Negro community that would not be tolerated in some other sections of the city.” He wrote that, along 63rd Street in the South Side’s Woodlawn neighborhood, “Prostitutes, male homosexuals and drug addicts arrogantly paraded along the street with the air that it was a badge of honor to be this sort of scum.”80 For black aspirants to middle-class status, social and sexual deviance increasingly seemed not simply offensive but a threat to racial uplift as well.

Inkblots and Individual Rights

In the midst of continuing police harassment and media-generated sex-crime panics, as well as a nascent national movement for African American civil rights, Chicago’s homophile movement took shape. By some twist of fate, Chicago had been the site of the nation’s earliest gay-rights organization yet uncovered, the Society for Human Rights, founded in 1924 by Henry Gerber, a postal clerk and Great War veteran living on the city’s North Side. The group was quickly shut down by the police, its files confiscated, and Gerber let go by the post office. In 1940, a pen pal asked Gerber about forming an organization for homosexuals. “Let me tell you from experience,” he replied, “it does not pay to do anything for them. I once lost a good job in trying to bring them together.”81 Still, Gerber’s activism illustrates the transatlantic influence of Magnus Hirschfeld and other German sexologists, and it was a precursor to the American gay movement of the postwar period.

The homophile movement began decades later among white liberals, most of them men. Mobilizing around an individual-level trait not shared with family members, such as one’s homosexuality, often entails spatial and emotional distancing from one’s family and neighborhood of origin. For this reason, participating in such a movement was perhaps inevitably both less attractive to and less possible for black than for white Chicagoans. In the working-class queer city, to be sure, there was some crosstown traffic. An African American male-to-female transgender Chicagoan living on the South Side recalls that she “was always up on north side, in and out of there,” especially the mostly white, bohemian and queer enclave of Old Town, where she encountered a multiracial transgender social network—including other street queens who “introduced me to the doctor they were getting their hormones from.”82 But the racial segregation of Chicago’s neighborhoods and workplaces curtailed the possibility of interracial queer political mobilization.

To most gays and lesbians in the early Cold War era, the risks of forming an organization based on their sexual orientation collectively outweighed the potential benefits. In the late 1940s or early 1950s, Shirley Willer was a young nurse in her twenties when a gay male friend died in a Catholic hospital in Chicago. Willer believed that her friend received inadequate care because he was perceived to be gay. Along with perhaps five friends, she recalled, she went to see a lawyer named Pearl Hart to ask about starting a formal organization of gays and lesbians. “We asked Pearl how you went about starting a group, and she said, ‘You don’t. It’s too dangerous.’” At that time, Willer said, “Pearl was like everyone else. She felt that people would get further by simply doing things quietly without announcing themselves.” Willer abandoned the notion of founding an organization and instead established an informal network of mutual aid. “Nothing came of that meeting, no formal organization, so my girlfriends and I did things pretty much on our own,” Willer recalled. “We took in young women and sometimes young men who had been thrown out of their homes.” She felt her nurse’s salary enabled her to help these young people, who “wouldn’t take jobs where they would be in danger of being fired because of being gay” and consequently took “the dirty jobs, the rough jobs.”83

It was not until 1954—after the California-based Mattachine Foundation had reorganized as the Mattachine Society, at its spring 1953 convention—that Midwesterners formed their first homophile group since Gerber’s. The Mattachine chapter in Chicago produced a newsletter from mid-1954 to early 1956, which published detailed, often quite well-written book reviews challenging literary conventions of gay representation. In 1954 and 1955, the Chicago group sponsored both closed and public discussions of such topics as “The Deviate and His Job” and “The Ethics of the Sex-Deviate,” as well as book discussion groups and fund-raising art sales. Participants in Chicago’s first homophile group looked to its West Coast progenitor as a model. One Mattachine member reported in the group’s newsletter about a trip to the West Coast: “The Society in San Francisco is probably further removed from the organizational growing pains Chicago has.” He was impressed, he said, that Mattachine Society pamphlets were available in the waiting room of the city health department’s outpatient clinic. The man reported that a police crackdown then under way in the City by the Bay “has the approval of most deviant residents of the city” because it focused on “that minority of deviants whose promiscuity in public places is flagrant and objectionable.”84 Thus, if California was frequently held up as a model, the example was not necessarily always a radicalizing influence.

Chicago’s early homophile activists, like their counterparts in coastal cities, used a patriotic rhetoric that suffused much of American life in the early Cold War. Yet, however eager they were to integrate themselves into postwar society and assert a respectable image, homophile organizers also included many leftists, who deviated in other ways from the postwar consensus. Pearl Hart, the crucial figure in the emergence of the homophile movement in Chicago, emerged out of left-wing politics (see Figure 2). Born in 1890 and raised Jewish in Traverse City, Michigan, she belonged to a generation in which there were almost no women attorneys, but she practiced law in Chicago from 1914. In 1933, Hart became a public defender in Chicago’s Morals Court (later the Women’s Court), where she improved the legal representation, and sharply reduced the conviction rate, of women arrested on prostitution charges.85 Active in the Henry Wallace presidential campaign and the National Lawyers Guild, Hart was described by the journalist I. F. Stone in 1953 as “famous throughout the Midwest for a lifetime of devotion to the least lucrative and most oppressed kind of clients.” She defended immigrants and Communists charged under the anticommunist Smith Act of 1950. She argued before the U.S. Supreme Court, and won, a 1957 case limiting the power of immigration officials to ask an alien awaiting deportation questions about how he used his free time and what newspapers he read.86

FIGURE 2. Pearl M. Hart, date unknown. Courtesy of Gerber/Hart Library and Archives.

Hart never identified herself publicly as a lesbian, even though she did more than any other Chicagoan in the 1950s to advance gay rights. Renee Hanover—who later said she came to Chicago as part of the Communist Party underground in the 1950s, then became Hart’s student at John Marshall Law School in downtown Chicago, and finally joined her in opening a legal practice focusing on cases affecting women—recalled how Hart managed being both a lesbian and a lawyer. When they met, Hanover recalled after Hart’s death, “of course she knew I was queer and I knew she was queer; I didn’t think that she knew she was queer. To know Pearl is to know this [feeling]! … She really felt that one’s personal life was one’s own.” She was “very conservative in that way. But not conservative in terms of gay community cases. She’s the one person who would take these cases.”87 She was accustomed to representing clients despised by mainstream commentators.

Indeed, as with homophile groups in every city, organizing was hampered by the fact that pseudonyms were the custom. One of the original Chicago Mattachine chapter’s first newsletters reported that the group had “formally approved Mr. Frank Beauchamp, who had generously offered to relinquish his privilege of anonymity as a member of the Society,” and this would allow the group to “proceed to the next step toward legal recognition under the Illinois Not for Profit Corporation Act.”88 After its address was published in national Mattachine Society literature, mailed by the San Francisco headquarters, the organization received correspondence from readers across the Midwest. “From Illinois, Indiana, Michigan and Ohio came offers of help,” wrote the newsletter editor, and “leaders throughout these States also inquired about forming chapters in their own communities.”89

Police harassment in 1954 was harsh—yet it did not have as much of the legal architecture of the state backing it up as would be the case a decade later. The complaints described in the Chicago Mattachine Society newsletter in this era focused more on the risk of exposure in the workplace than on police practices (though, of course, the latter could and often did precipitate the former). Indeed, there was no discussion of the Chicago police department in the newsletter at any point during the chapter’s first incarnation. Only one article that appeared at that time directly took up the question of the state—rather than religious and medical authorities—as persecutors of gay people, and that article lodged its complaint not against the city or state but against the federal government, as well as against corporations influenced by the example of discrimination that federal policies offered. “Not only has the Federal Government expressed its aim to refuse to employ homosexuals for the sake of ‘tightening security measures’ or ‘improving moral standards,’” wrote the author, who published only under the initials J. B., “but an increasing number of private businesses are following the Government’s lead.” The author explained that federal policies had altered the climate for gay employees of local private firms. “Investigative agencies purporting to be miniature FBI’s,” observed another article in the Chicago Mattachine newsletter, “have sprung up to meet this demand for employee screening. Listed on the letters of one of these local agencies are the ‘undesirables’ this agency specializes in ferreting out; in bold print ‘homosexuals’ stands out.”90 Some local employers had, unfortunately for gay people, begun to take their cue from the federal government.

However timid by the standards of a later era, the Mattachine newsletter talked back to a culture that relentlessly demonized gay people. “In America at least,” sociologist Erving Goffman wrote in his influential 1963 book Stigma, “no matter how small and how badly off a particular stigmatized category is, the viewpoint of its members is likely to be given public presentation of some kind.”91 After a psychiatrist spoke at one Mattachine meeting and advanced the view that homosexuality could be treated and cured, the editors published letters of complaint from members. After the philosopher Gerald Heard spoke at an early meeting, one member wrote a letter denouncing Heard’s claims as pretentious: “As for [his] notion that the ‘intergrade’ has this great creative potential because he’s ‘relieved of the burden of procreation’—well, just ask the average invert where most of his energy goes.”92 The organization engaged in fledgling dialogues with activists in other cities, comparing their predicaments. Chicago’s Mattachine chapter held a daylong benefit art show, during which viewers watched a recording of a 1954 local television program, which had been shipped from Los Angeles, where it was taped, and which most members apparently found disappointingly unsympathetic toward gay citizens.93

The Chicago Mattachine group also engaged in a surprisingly bold project to help produce knowledge about homosexuality. Inspired by the path-breaking research of Evelyn Hooker, the psychologist and expert on gay men’s mental health, its members volunteered to take Rorschach inkblot tests for the cause. They also recruited their friends to participate in Hooker’s research. In retrospect, this may have been the chapter’s most important contribution to gay equality. The collaboration began in 1954 when Hooker stopped in Chicago on a cross-country trip to meet with chapter members. Her work was pioneering because, unlike previous scholarship, it did not rely on convenience samples made up solely of those gay men who sought a cure or had trouble with the law but instead recruited participants from homophile groups.94 After Hooker’s visit, the Mattachine group “offered its services in obtaining 37 volunteers” to take Rorschach inkblot tests for a Chicago doctor interested in studying “non-institutionalized homosexuals.”95 Hooker cited her conversations with Chicago Mattachine members, along with their counterparts in San Francisco, New York, and Los Angeles, in her first published account of this research on gay men’s mental health, which she presented earlier at a 1956 conference in Chicago and published that same year in the Journal of Psychology.96

Despite such activities, the Chicago Mattachine group had trouble staying afloat. By mid-1956, San Francisco activist Hal Call visited Chicago and pronounced the chapter “practically dormant,” reporting a high level of fearfulness on the part of the gay Chicagoans he met, and no newsletters appear to survive from after the summer of 1955.97 During a brief revival in 1957, the Mattachine members managed little more than to publish a pamphlet—although a significant one—written by Pearl Hart, titled “Your Legal Rights.” The pamphlet might best be summarized as a description of what was likely to happen to a gay man or lesbian—though it referred only to “individuals,” not homosexuals—after being arrested.

The focus of the pamphlet was on laws used against gays. The main right emphasized was the right of an arrested person not to answer questions. “No police officer,” said the brochure, “has a right to question a person who has committed no offense, and the law does not require the person to answer indiscriminate questioning because the police happen to be making an investigation, or because there is a so-called ‘crime wave.’” The pamphlet also included a list of Illinois criminal offenses that “are frequently invoked against individuals,” including laws against public intoxication; patronizing or maintaining a disorderly house; “the infamous crime against nature”; the commission of lewd, lascivious, wanton, indecent, or lustful acts in public; and that broadest charge, “disorderly conduct.” The Mattachine Society’s Chicago Area Council, as it was known, offered the leaflet through the mail for 25 cents.98

“Your Legal Rights” drew heavily on patriotic rhetoric, claiming that the “founders …, wisely foreseeing the necessity for limiting the extent of the law and the methods of its enforcement, drafted the Bill of Rights.” The pamphlet, even while framing its topic as the rights of “individuals,” not homosexuals, gamely evoked the emotional tenor of bar raids and similar forms of police harassment: “the primary need for many arrested persons is to eliminate the feeling of fear which so many entertain because of lack of knowledge of legal procedures.” But the “rights” described in “Your Legal Rights” were in fact rather few, in this age before Miranda and other legal precedents that augmented the rights of criminal defendants. For several brief periods in the 1950s, Chicago’s gay men and women organized to give voice to their frustrations over police harassment and social and political marginalization. But it would take a national movement for civil rights to show them how to organize effectively.

* * *

In the second half of the 1950s, periodic sex-crime panics continued to result in police harassment of gay men. When a fifteen-year-old girl’s body was found in Montrose Harbor in 1957, for example, the 44th Ward Republican committeeman, Robert Decker, railed against the leniency of judges in “loosing sex degenerates upon our streets,” while Democratic alderman Charles H. Weber from the neighboring 45th Ward added that “if we want to protect the youngsters, we’ll have to organize a campaign to get [them] off the streets after dark and go after the sex maniacs who make our streets dangerous.”99 After another gruesome murder on the North Side in 1960, a crime reporter said, “In the area, police know that a number of men with criminal sex records live and work,” adding that they had been questioned.100 “Chicago had quite a ‘heat wave’ this year,” wrote a columnist for the Los Angeles–based homophile magazine ONE in mid-1959, using a meteorological metaphor that both punned on a slang term for police and reflected an era when police repression seemed to many gays and lesbians like a force of nature.101

At the same time, even though Chicago was the scene of intense—and intensifying—policing, gay citizens could sometimes carve out space for themselves in a city where the establishment was well known for corruption and graft. Chicago’s Mattachine chapter struggled to attract more than a handful of members in the 1950s, but it offered a response to the increasingly systematic policing of gay life by local authorities and to the isolation and exclusion from mass society that gays and lesbians felt. Though marginal and lacking influence in the 1950s, the movement’s emergence paved the way for more ambitious mobilization in later years.

In the 1950s, moreover, gay bars only erratically enforced rules against intimate contact between patrons because vice control was relatively uncoordinated and decentralized. As late as 1961, a visitor describing the Front Page Lounge on Chicago’s Near North Side—one of the city’s most crowded and most popular gay bars—wrote, “Dancing is allowed. They say that no close dancing is allowed, but very seldom stick to the rule.”102 By the mid-1960s, however, as we will see in the next chapter, most bars would enforce a strict prohibition on same-sex dancing altogether, as the police department’s ability to suppress gay life had been dramatically increased. By the mid-1960s, gay citizens would come to feel more harassed by the Chicago police than by the military, psychiatrists, or the federal civil service, and they would think back to the 1950s as a time of relative freedom.