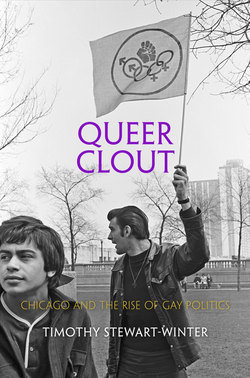

Читать книгу Queer Clout - Timothy Stewart-Winter - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

___________

IN 2013, the chief justice of the United States suggested that the gay-rights “lobby” was so “politically powerful” that gay couples denied equal access to marriage should not be considered a disadvantaged class deserving protection from the courts.1 And yet, only fifty years ago, gays and lesbians were social and political pariahs, facing harassment wherever they gathered. This book traces that trajectory—from the closet to the corridors of power—and chronicles the rise of gay politics in the postwar United States.

The path of gays and lesbians to political power led through city hall and developed primarily in response to the constant threat of arrest under which they lived. Their eventual victory over police harassment, secured by allying with other urban residents who were policed with similar vigor, especially African Americans, was the prerequisite for their later triumphs. By the late 1980s, in cities where politicians had only recently sought political advantage from raiding gay bars and carting their patrons off to jail, gays and lesbians had acquired sufficient power and influence for elected officials to pursue them aggressively as a potential voting bloc—not least by campaigning in those same bars. Gays now had clout.

Gay migration to cities was a major feature of postwar urban life, one that consequentially shaped urban liberalism. After World War II, unprecedented numbers of émigrés from smaller cities, towns, rural areas, and suburbs left their families of origin and joined urban gay society, where they learned they could find both anonymity and community. As Carl Wittman wrote of San Francisco, in the most influential manifesto of the gay-liberation movement, “We came not because it is so great here, but because it was so bad there.”2 In subsequent decades, the gay-rights movement flourished and drew in predominantly white and middle-class city dwellers. As urban gay communities swelled with newly out and newly arrived gay people, their desire for recognition and their need for government protections began to realign the political views of a small but growing minority. In growing numbers, gays and lesbians chafed against their outcast status; they demanded that local government, and particularly the police, treat them as rights-bearing citizens.

The rise of the gay movement in postwar America was shaped by a liberal faith in civil liberties as well as, in the 1960s, by the Vietnam-era antiwar movement, the hippie counterculture, and the rebirth of feminism. In Chicago, where gay mobilization was weaker and routine police raids persisted longer than in the vanguard cities of New York and San Francisco, gays and lesbians joined an emerging coalition. A key factor enabling them to challenge police harassment successfully was the example of demands by blacks for police reform, and what enabled gays and lesbians to gain power—a toehold in city hall—was the emergence of progressive, black-led local electoral coalitions. The gay movement flourished in the soil of urban politics not only because gay people were concentrated in major cities but also because it was in big-city municipal government that African Americans and their white allies criticized police practices, demanded reform of the criminal-justice system, and called for inclusion and tolerance as governing ideals.

As the Democratic Party began slowly to recognize the demands of blacks and Latinos, women, and gays and lesbians, black elected officials were instrumental in cementing the importance of gays and lesbians in the new electoral coalition. The black civil rights movement provided gays not only a model but also new opportunities to gain visibility and influence at the municipal level, as black and white liberals broke open urban machines and rejected traditional political structures they viewed as corrupt and unfair. As police harassment diminished and as more gay people came out and realized they had no recourse if they were fired for being gay, they again turned to the civil rights model developed by African Americans to seek legislation to protect them, and to black elected officials to defend their civil rights. For reasons of both pragmatism and principle, African American big-city mayors in particular sought to cultivate the gay vote.

This book traces the political effects of a neglected convergence that saw blacks and gays constitute an increasing share of the urban population after white flight to the suburbs. In this period, gays and lesbians asserted a “right to the city” in a way they had not done before. They signed petitions, wrote articles, asked to meet with police commanders, filed lawsuits, and marched in the streets. In urban America, beginning in the early 1960s, gay activists learned from the tactics of African Americans who challenged police brutality through protests and lawsuits. In Chicago, as black and white liberals acquired influence in the 1970s, gay activists joined a coalition that resisted police extortion, spying, and surveillance. Driven together by their shared concern with combating the overzealous activities of law enforcement, black and gay activists sometimes found common cause with one another in the face of police harassment. These fragile alliances ultimately foundered in part because, ironically, in the very years when policing and punishment in black neighborhoods began to increase, the policing of predominantly white gay establishments and neighborhoods became far less systematic.

Much has been written about the rightward turn of American politics in the late twentieth century. And indeed all three branches of the federal government remained implacably hostile to gay mobilization into the early 2000s. But in the last quarter of the twentieth century, every major U.S. city enacted laws that its gay citizens had demanded. The gay-rights movement flourished later in the century than the other rights-based social movements on which it was modeled, and the character of gay politics bears the imprint of the 1980s and 1990s. The so-called gayborhoods on Chicago’s North Side, dotted with businesses owned and patronized by gay men and by a smaller number of lesbians, reflected the uneven neoliberal economic development of metropolitan neighborhoods. By the 1990s, when gays and lesbians had mobilized to forge new institutions and to make new demands, government’s capacity to remedy injustice had atrophied, and the toolkit for the delivery of services had changed. The acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) crisis created a desperate quest for funds just as the federal government turned its back on cities. New programs serving people with AIDS and homeless lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth were administered by a growing nonprofit sector. However vigorously advocates strove to deliver services where they were most needed, they could not undo the growing impact of metropolitan segregation by race and class—even as the AIDS crisis worsened the impact of those inequalities.

* * *

Queer Clout draws together the histories of a social movement and electoral politics in the nation’s great inland metropolis. Compared to the better-known stories of San Francisco and New York, the story of gay empowerment in Chicago was in many ways more representative of the dozens of other regional magnets for gay migration—from Atlanta to Seattle, Boston to Dallas. Gay migrants to urban America, no matter how numerous, have always been culturally significant despite being difficult to count. Like members of racial and ethnic minorities, their demographic quantification requires decisions about who belongs inside the group and who outside. The politics of the closet overlay these questions with a profound methodological problem: Until very recently, respondents to social surveys were typically unwilling to self-report such a concealable and highly stigmatizing trait to a stranger. Still, urban life held out the prospect of pleasure, and gays and lesbians, like African Americans, played an increasingly important role in the remaking of the American metropolitan landscape in the postwar decades.

As the industrial and population boom of the World War II years subsided, African Americans continued to migrate to the urban North. Yet many large cities, including Chicago, began to lose population to suburbs. While federal urban-renewal dollars flowed into programs that cleared or demolished struggling inner-city neighborhoods, in an attempt to reverse “blight,” far more money was used to subsidize the movement of white-collar workers and corporations to sprawling suburbs where land was cheap. Gay migration to cities in the postwar era—what anthropologist Kath Weston has called the “great gay migration”—represented a trend that countervailed the much larger migration of whites to suburbs.3 Far from gaining clout by virtue of their growing numbers, however, gays and lesbians were largely understood as people engaged in deviant behavior and as evidence of vice, decay, and disorder—not yet as a community, much less a political constituency. Routine police raids on gay establishments endured even in the most liberal places for as long as a decade after the 1969 Stonewall uprising in New York, traditionally considered the beginning of the gay-liberation movement.

Gay people most often came together to improve their lot by means other than formal political mobilization. In part because of public hostility, the mutual aid that lesbians and gay men provide one another tends to be informal, even invisible. In the late 1990s, a lifelong Chicagoan from the South Side, then in her seventies, recalled, “There was a girl who worked at Bell & Howell out in Lincolnwood, and she was black and gay, and she did the [job] interviewing.” In fact, she said, “There was almost a whole production line of cameras and projectors that were nothing but gay girls.… She made it her business to hire every gay girl on the South Side that she could hire. So a lot of us got in at Bell & Howell.”4 This individual’s quietly undertaken project—“her business”—is the reason both for its success and for its failure to leave an archival trace. Such networks emerged in every community, largely hidden from the straight majority, and they were especially crucial for women, African Americans, and others who, facing marginalization in multiple ways, were often less drawn than were white men to organize around their gay identity.

In the half century following the emergence of the American gay-rights movement, the story of gay politics was inseparable from that of big-city government in places such as Chicago. In America’s large cities, gay and lesbian citizens won an end to routine police raids on gay establishments, the right to parade annually through city streets in celebration of their community, and legal protection against antigay employment discrimination. Many lesbians joined the women’s movement and worked to expand protections for women living independently from men. Although the federal government legitimized the civil rights revolution in the 1960s, it was urban municipal government that expanded its scope to embrace gay men and women in the decades that followed.

Historians of queer politics have tended to emphasize the differences between the homophile organizations of the 1950s and 1960s, on the one hand, and the gay-liberation movement that flourished after the Stonewall uprising and developed into a far larger and more complex social movement, on the other. This book instead emphasizes the continuities between the 1960s and 1970s, as activists from both generations focused on challenging police brutality, entrapment, and street harassment, as well as raids on gay bars. Their concern with policing distinguished the homophile and gay-liberation movements from the movement organized around AIDS that arose later.5

Harassment by big-city police departments was the gay movement’s first policy focus; even an arrest for disorderly conduct, or another nebulously defined crime, in practice could mean losing control over who knew about one’s sexuality. This harassment was as harsh in Chicago as in any American city. In a 1967 police raid in which seven patrons were charged with indecency, eight plainclothes detectives had entered the bar separately in order to observe the activities there and establish the grounds for the charges. The next morning, a sociologist studying gay life, who heard about the raid and arranged to interview bar manager immediately, expressed surprise at the sheer number of police officers involved. “Right,” said the manager. “They do things big in Chicago.”6 The fear of arrest thus powerfully affected even the many gays and lesbians who were never themselves taken into custody. The decline of antigay police harassment—a story told here as it unfolded in one large city and which took place in some form in every large American city between the late 1960s and the late 1980s—has been almost totally neglected by historians.

Gay rights became a tool by which newly empowered African American elected officials could expand their appeal among an increasingly important segment of urban white voters. Chicago’s aldermen recognized that, given the small size of each city ward and the low voter turnout characteristic of local elections, a motivated segment of voters held the power to decide their futures. As an insurgent black progressive and a reformer, Harold Washington perceived white gays as whites who might vote for him in very close citywide races based on his support for gay rights. Washington was the first mayor of Chicago to welcome gay people to city hall—indeed, his staff warned him that the members of his gay advisory committee lacked political savvy and that most “have very little experience with politics and city government”—but he would not be the last.7 Identifiably gay voters were also important because as they became visible, they were concentrated along the North Side lakefront, in crucial swing wards in the city’s racially charged political battles of the 1980s. In addition, the relationship between black and gay politics was not unidirectional. For example, predominantly white gay voters in a key ward joined Latinos in gradually tipping the balance of power in the city council to Washington by mid-1987.

And this was not just in Chicago. Embracing gay rights helped a startling number of black mayors win election or reelection around the country: Tom Bradley in Los Angeles, Coleman Young in Detroit, Marion Barry in Washington, Wilson Goode in Philadelphia, Maynard Jackson and Shirley Franklin in Atlanta, and David Dinkins in New York. Black politicians in the 1980s thus helped forge a coalition around a progressive politics of sexuality and gender, a coalition that would become even more visible nationally in the 1990s. One striking aspect of this story is that antigay black pastors were not an obstacle to the successful alliance between black and gay politicians. Indeed, Catholicism influenced council members not because of grassroots mobilization but because of institutional ties. Although few have argued that Roman Catholic antigay mobilization is “white” homophobia, at least in Chicago the Catholic archdiocese exercised far more influence on white politicians than socially conservative black pastors did on black politicians.

The urban character of gay politics sheds light on its radical roots, its growth in a neoliberal era, and its contradictory present. This book seeks to uncover the origins of gay politics as a remarkably effective challenge to the violence of state power at the local level. Influenced by the antiwar, women’s liberation, and black-freedom movements, gays and lesbians increasingly sought a place within the world of party politics in the late 1960s and 1970s. The gay-pride marches of the 1970s, through the insistence of gays and lesbians on coming out, helped create the conditions that allowed middle-class, identity-based urban gay communities to emerge—something previously impossible because, with very few exceptions, holding down “good” jobs required the careful concealment of one’s homosexuality. As the negative consequences associated with being identified as gay slowly lessened, an increasing number of middle-class urban gay communities became visible and even political.

It was in the 1970s that gays and lesbians made their most important early strides toward participating in local government as a recognized constituency. The movement for political reform that swept through much of American political culture in the 1970s had many effects on American life, but perhaps no community was more deeply affected than that of gays and lesbians. It was in this era that gays began to be a Democratic Party constituency. At a conference held in Chicago in February 1972, inspired by the Democratic Party’s new rules requiring that minority groups and women be proportionally represented among convention delegates, gay activists from across the country passed a resolution demanding that 10 percent of the party’s convention delegates be gay.8 Even this early, it seemed less likely that the Republican Party would be responsive to such requests for inclusion. That perception had hardened by the late 1970s, as GOP leaders began to align the party’s platform not with the feminist and gay-rights movements but rather with the developing religious conservative backlash against those movements’ gains and visibility.

In the 1980s and 1990s, urban America was increasingly constituted as a bastion of liberalism. Although the nation’s cities did not turn rightward as sharply or as quickly as the federal government did in the late twentieth century, the nation’s retreat from the redistributive welfare state and the latter’s supplantation by neoliberal institutions increasingly shaped big-city politics, eroding some of the dreams of radical and progressive gay activists. By the time militant AIDS activism emerged in the 1980s, the gay movement’s claims of police brutality centered almost exclusively on police behavior during arrests of activists engaged in civil disobedience, as well as on the frequent and medically unwarranted use of rubber gloves by police interacting with activists. In the late 1980s, gay activists confronted repressive legislation aimed at curbing the spread of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and AIDS, beating back many such proposals at the local, state, and federal levels, but they failed to block a new threat in the form of statutes criminalizing HIV transmission, laws that reinforced inequalities in the legal system.

While black and gay activists and politicians forged important political ties in the 1970s and 1980s, the social basis for black–gay alliances began to break down. In a city legendary for its racial bifurcation, the geographic centering of gay politics on the white side of town hardened a perceptual link between gayness and whiteness. In Chicago, a city-sponsored, $3.2 million gay-themed streetscape renovation project completed in 1998 in the North Side’s East Lakeview district, whose commercial strip was by then known as “Boystown,” epitomized the symbolic use of public funds to promote tourism by a means that, like any public project, benefited lawyers and contractors working for the city. The uneven economic development of North Side and South Side neighborhoods brought about tensions over policing and programming, and the AIDS crisis worsened those tensions by overlaying them with conflicts about respectability. A more conservative generation of black clergy began to gain clout just as the gay movement turned its focus from policing and job discrimination, which many urban blacks readily understood as matters of civil rights, to the thornier and more symbolically charged issue of marriage equality.

Even as urban white gays shook off the burden of routine police harassment and worked with police officials to institute sensitivity training and to recruit gay officers, racial tensions developed between those white gays who increasingly wielded local political clout and the queers of color who remained subject to disproportionate incarceration. Gay activists even began at times to respond to antigay violence with calls for intensified policing, a move that black, Latino, and other activists of color have resisted.9 As recently as 1991, Chicago’s police department had had no openly gay officers.10 Breaking into law enforcement was a powerful and hard-fought alteration in the status of a group that remained a criminal class under sodomy laws in effect in more than a dozen states until 2003.11

The development of gay politics also shows how urban politics remained persistently gendered, as many more gay men than lesbians entered the clubby world of municipal politics. Relations between lesbians and gay men changed over time, but the struggle for gay rights always involved both. Lesbians suffered doubly from the economic discrimination of a gender-segregated metropolitan job market in which women earned far less than men. As gay-male and lesbian communities grew in the 1970s and the barriers to gay organizing fell, the two communities diverged politically on issues of consumption, sex, and objectification. A decade later, the devastating AIDS crisis paradoxically brought gay men and lesbians together. As late as the early 1970s, there were no female precinct captains in the legendary political machine over which Chicago mayor Richard J. Daley had presided since the mid-1950s. Some women gained access to the levers of power; indeed, Chicago’s Jane Byrne became in 1979 the first female mayor of an American metropolis. Many gay organizations adopted policies to ensure gender parity. Yet men still had far greater access to the pinstripe patronage and campaign money that were increasingly important to local politics. “Boystown” became the center of Midwestern queer political culture in the 1990s, suggesting that the fundamentally masculine character of urban politics was reproduced in its gay variant rather than displaced altogether.

Because of its urban beginnings, the gay movement was more radical in its origins than historians have yet recognized. But as it became embedded in American public life, it reflected the contradictory character of the society in which it emerged: a society increasingly tolerant of sexual and gender diversity and willing to guarantee the civil rights of people with disabilities, gays and lesbians, and other emerging constituencies, and yet also marked by deepening economic inequality and a shrinking social safety net. Urban politics allocated clout to some gay men, and to a smaller number of lesbians, even while it marginalized many other gay and transgender citizens. Gay politics reflects neoliberalism and budgetary austerity not because of the gay-rights movement’s intrinsic conservatism—indeed, radical and left-liberal figures were among the most important catalysts in legitimizing the gay movement—but because of the historical and geographic context in which it matured. In Chicago, gay political activism began to shape aldermanic races in a string of wards along the North Side lakefront. Some elected officials—even those outside these wards and seeking citywide office—began to take notice of their behavior. But their ascent to power remained tentative until the 1990s. Indeed, as recently as 2004, when many states enacted constitutional amendments banning same-sex marriage and when an antigay president won election to a second term, the gay-rights movement seemed to many to be losing ground.

Gays and lesbians have rapidly consolidated their political influence over the past two decades. Not long ago, however, the political marginality of gays and lesbians even in urban America seemed to confirm the definition of homosexuals offered by the character Roy Cohn in Tony Kushner’s Pulitzer Prize–winning play Angels in America as “men who in fifteen years of trying cannot get a pissant antidiscrimination bill through City Council,” who have “zero clout.”12 That Kushner’s Cohn cited the long battle to ban antigay discrimination in New York City—finally successful in 1986—is telling. Gay rights were won in the cities.

* * *

This book combines the two leading methods that have characterized gay and lesbian history: the community study, which describes the first generation of scholarship on both movement activism and everyday life, and the more recent emergence of political histories, which typically center on the federal government and examine the negative effects of state power on gays and lesbians, not the dynamics of the gay movement at the national, state, or local levels.13 By casting gay political empowerment as an aspect of urban liberalism, this book explains the roots of the movement’s subsequent successes during the past decade at the federal level. The urban character of gay politics cannot be understood without taking seriously the crucial role that local and state governments played in the political reorientation by which social issues, such as sexuality and gender, moved from the margins to the center of American politics.

Queer Clout remedies a dearth of archive-based studies of gay politics after 1970. Monographs on social-movement history have fleshed out aspects of the homophile, gay-liberation, and women’s liberation movements.14 Partly because there are so few historical studies of gay politics after 1970, however, postwar historians generally have interpreted the growing electoral significance of social issues almost exclusively for its role in consolidating political conservatism.15 One factor contributing to this problem is that until 2003 nearly all of the gay movement’s successes took place at the state and local levels, out of sight of political historians who strongly emphasized the centrality of the federal government in American life since the New Deal era.

Although many scholars have examined the influence of the black-freedom struggle on subsequent mobilization by other groups, this book offers one of the first accounts to extend that approach to the gay movement—tracing the arc of that influence and taking stock of its complicated effects and dynamics.16 Unpacking what happened on the ground in a particular city is a method well suited to examining this problem.17 It also builds on works that examine the police and law enforcement in relation to gay life and politics,18 as well as on the scholarship tracing the intertwined histories of race and sexuality, bringing this approach to bear for the first time on the critical setting of urban politics in the post–civil rights period.19 Informed by the empirical work of Cathy J. Cohen and Russell K. Robinson, it extends the queer-of-color critique in sexuality studies by providing the perspective of an archive-based political history.20

Because gay politics until recently was urban politics, its emergence comes into clearest focus through a case study of a single city. Chicago is a major regional transportation hub and one of the nation’s largest cities, and it drew gay migrants from across the Midwest. As a major battleground of the civil rights struggle in the urban North, moreover, Chicago offers a chance to examine closely the gay-rights movement’s changing relationship to the black freedom struggle. In part because so little has been written on gay political history, the exceptional stories of New York and San Francisco—notably, the Stonewall rebellion in New York and the election of Supervisor Harvey Milk in San Francisco—have inflated the national significance of events that were in many respects local.21 There were turning points in the history of Chicago’s gay politics, but such exceptional stories as the Stonewall uprising and the election of Harvey Milk, were not among them. This book focuses, instead, on how gay politics developed in relation to key moments in the life of local politics, such as the Democratic National Convention, held in Chicago in August 1968, and the election of Harold Washington as the city’s first black mayor in the spring of 1983.

Chicago was the birthplace, in the 1920s, of the nation’s first, short-lived gay-rights organization, which quickly collapsed because of police harassment, and it was one of only four cities—along with New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco—where the first annual gay-pride marches were held in the summer of 1970. Yet it was never one of the coastal gay meccas—like San Francisco and New York—that was so open to gay mobilization as to be unrepresentative of urban America as a whole. Indeed, Chicago may also be the largest American city without a strong popular association with homosexuality. Chicagoans sued for the right to operate a gay bar later than did their counterparts in New York and San Francisco.22 Of the five most populous U.S. cities in the 1980 census, Chicago was the last with a gay-rights ordinance, passed in late 1988.23 Gay politics there drew on local frames, events, and demographic shifts. Chicago, in short, offers the advantage of studying a large city with national importance that still claims a degree of representativeness that its coastal counterparts cannot.

This book introduces the reader to women and men who created a social movement far from the coastal meccas—where, after all, only a small minority of the nation’s gays and lesbians lived. As gay Chicagoans struggled to respond to police crackdowns in the 1950s and 1960s, they turned to the criminal lawyer Pearl Hart, a radical Jewish woman from Michigan who had graduated from John Marshall Law School in the Loop before World War I. In the 1930s, she defended prostitutes in Chicago’s Women’s Court and helped found the left-wing National Lawyers Guild, and in the early Cold War she became nationally known for defending leftists charged under the Smith Act. Hart also defended countless gay men arrested in Chicago’s gay bars and tearooms. Beginning in the mid-1950s, when she was in her mid-sixties, and for two decades, she advised nearly every Chicagoan who struggled, against the powerful forces of the closet and of a conservative era, to forge a homophile movement.

In the 1970s, Chicago’s most vocal and passionate champion of enacting gay rights legislatively, Cliff Kelley, emerged not out of the gay-liberation movement but out of the 1969 Illinois constitutional convention, and the broad movement of civil rights challengers to the regime of the Jim Crow North. Kelley, a brilliant black liberal iconoclast, was born in the South Side’s Washington Park neighborhood during the flood of black migrants seeking industrial jobs during World War II. Witty, idealistic, and intellectual, he introduced his gay-rights ordinance year after year, holding hearings, tweaking his arguments. At one point, Kelley, who said he was straight, told a newspaper reporter that he couldn’t enact gay rights in the city council because some of his colleagues “have masculinity problems or are secret bigots.”

Kelley’s virtues were characteristic of his native city, and so too was the vice that brought about his political downfall. After sixteen years of service as an alderman, he was indicted in 1986 for accepting bribes from waste contractors doing business with the city, pled guilty the following year on a lesser mail-fraud charge, and served nine months in a minimum-security federal prison. After his release, he reinvented himself as a radio talk-show host, where he could be heard for many years on WVON-AM radio (“Voice of the Negro”), Chicago’s sole remaining black-owned station. In 2000, he moderated the only campaign debate between the incumbent, Congressman Bobby Rush, and his challengers, Donne Trotter and Barack Obama.

Kelley’s tragic flaw may have been as implausible as his heroic advocacy for gay rights. Perhaps, in a larger sense, it was nothing if not Chicagoan. We turn now to the place where these paradoxes emerged: the contradictory landscape of the postwar city.24