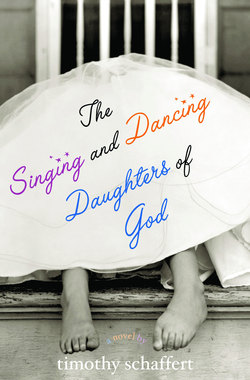

Читать книгу The Singing and Dancing Daughters of God - Timothy Schaffert - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1.

ОглавлениеTO get through the afternoons that wound into early evenings, driving a school bus along long country roads and driveways, Hud kept slightly drunk. He sipped from an old brown root-beer bottle he’d filled with vodka. There’d been a few times in the past when he’d gotten too drunk, when he’d swerved too much to avoid a raccoon, and even once a sudden hawk swooping too low. He made himself sick to think how he’d once nearly driven the rickety bus in all its inflammability into an electrical pole. He knew what an ugly notoriety such an accident would bring him. The whole world, Hud thought, likes to mourn together and hate together when it can.

There was a man in town named Robbie Schrock, who, like some fairy-tale hag, had murdered his own two boys with rat-poisoned candied apples he’d dropped into their Halloween sacks. When the children died, Robbie Schrock cried on the TV news and blamed the neighbors, and the whole little town cried with him, shocked by the inhumanity of some people. Robbie Schrock eventually confessed, and shocked the town all over again. The state tried and sentenced him and gave him the chair.

Today was the afternoon of the execution, and some of the children on Hud’s bus celebrated by dressing up in Halloween costumes, though it was only early September. One boy wore a bandanna and a pirate’s eye patch pushed up on his forehead. Another boy wore an Indian headdress and a breastplate made of sticks and feathers. A little girl was a Belgian nun in a pale blue habit and a winged wimple folded from newspaper.

Hud, disturbed by what he thought to be morbid spectacle, took a last shot-back of vodka from the root-beer bottle. He looked in the rearview mirror to the two boys sitting behind him. Both were dressed up in churchy blue suits, their faces painted a pale gray.

“What are you supposed to be?” Hud asked.

“We’re the murdered Schrock boys,” they said, their voices in tired and rehearsed unison.

“You’re the worst of them all,” Hud mumbled. He felt compelled to write a song for Robbie Schrock, though he’d hardly known the man and, of course, did not condone his crime. Whistling, Hud drove with one hand, and with the other he wrote down key words to the song coming together in his head. He wrote “lonesome” and “divorce” and “weakly” in ink on the leg of his jeans.

He understood something of Robbie Schrock’s circumstances. Hud’s newly ex-wife, Tuesday, at times was full of vindictiveness. For a short while she had conspired to keep Hud’s daughter away from him, judging him a drunk and a misfit and unworthy of even the few decent things this worthless world offered him. Robbie Schrock, his babies taken away, probably in an ugly divorce, probably left with only an occasional weekend or an occasional holiday with his children, wanted the whole world to know what loss can really do to a person. Hud could sympathize.

Though he would never hurt his own eight-year-old, his adorable Nina, he had thought about stealing her away, about painting his car a different color and driving and driving until they found some suitable no-place. They’d wear fake glasses, and when they spoke to the people at the gas stations and grocery stores, they’d cover their mouths with handkerchiefs to disguise their voices. He’d change the part in his hair and go by the name of some other Paul Newman character—Luke, maybe. Maybe Butch. Nina could choose her own name, would probably choose “Jessie”; that was what she named all her dolls.

Whenever with Nina, and only with Nina, Hud felt calm and attentive, and he thought if she was his all the time, he’d be a better man. A few weeks before, Tuesday had let Hud have Nina for an afternoon in his apartment above the shoe repair shop on the town square. Hud and Nina went up on the flat roof and harvested the tomatoes he’d grown in pots. Afterward, after eating some, Nina lay back to nap, seeds on her cheeks, and asked him to sing a song about her. He sat so his shadow kept the vicious sun from her skin, and he plucked a tune from his guitar. He called it “Nina Is All I Need, Really,” and as she drifted off, he sang about every aspect of her face, giving her nose, her pink lips, the red freckle on her neck, each its own separate piece of melody. This could be why people have children in the first place, he thought.

Hud and Tuesday had one other child, a seventeen-year-old boy named Gatling, a real retro hipster with a slick pompadour, cuffed jeans, and dice tattooed on his bicep. Or at least, that was how he looked when last they saw him. Since he’d vanished on the first hot day in May, they’d received only postcards; he was touring with a band called the Daughters of God, playing guitar and singing backup at revivals and fairs.

Gatling was the reason Hud and Tuesday had married so young, and he’d been a handful for years. Once last winter, practicing some new brand of discipline she had learned about at a seminar, Tuesday had locked Gatling out of the house for a few days for giving Nina a drink of his Windsor Canadian. “I knew she wouldn’t like it,” he’d said, and though it was only a tiny sip that had dribbled mostly down Nina’s chin, it had been the last bit of badness Tuesday would allow. And that was when he had started spending so much time at the Lutheran church, hanging out with a group of Jesus freaks and driving into Omaha with them to hand out pamphlets in front of rock concerts.

Gatling had also taken to scarring and cutting himself, had even carved all nine letters of his ex-girlfriend’s name across his chest in an act so romantically psychotic it had almost won him Charlotte back.

All Hud knew for sure was that so much had stopped seeming possible that afternoon in May when Gatling left. Hud remembered driving into the driveway, only seconds after Gatling had gone off for good on his Vespa, some ice cubes in the grass not yet melted despite the day’s uncommon heat.

After dropping off the last of his costumed passengers, Hud went home to sit alone and compose some lyrics. Robbie Schrock’s life seemed perfectly lived for a country song. Country songs, to Hud, were chronicles of destitution, haunted by beaten-dead wives and abandoned children. The key to an authentic country song, he thought, was to tell the story of a life lived stupidly and give it pretty strains of remorse.

Hud wrote: “He had the cheap kind of heart that broke when you wound it too tight.” Then he wrote: “He got all turned around on what was supposed to be wrong and what was supposed to be right.” Hud had spent many of the summer’s days, the days following the finalization of his divorce, at his kitchen table writing songs and drinking Mogen David red like it was soda pop.

Hud climbed out through his window and up to his roof. The town square was usually quiet at night, but people continued to celebrate the execution of Robbie Schrock. The costumed children strung toilet paper in the trees on the courthouse lawn and knocked on doors for handfuls of candy. There were costumed adults on their way to parties: a man in a cape and top hat and white gloves alongside a woman wearing only a long red magician’s box, her head and arms and feet sticking out, a saw stuck through the middle. A woman dressed as a nurse in blue jacket and white stockings pushed a pram jingling with bottles of liquor.

Hud, not amused, began to sing one of his more mournful songs, about a girl stung to death by wasps. He strummed a purple guitar. People passed in the street, but no one stopped to listen. No one wept for the man in the song sad about the death of his girl. No one even offered a knowing, sympathetic nod.

My neighbors hate me, Hud thought. They all knew and loved his wife. Tuesday taught art at the grade school, taught the town’s children how to make tongue-depressor marionettes and abstract paintings using slices of old potato. And they hate me now, Hud thought, only because I’m without her.