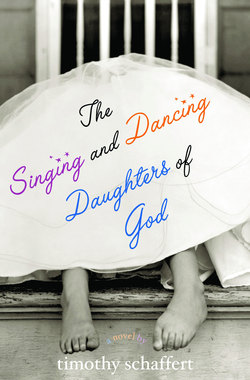

Читать книгу The Singing and Dancing Daughters of God - Timothy Schaffert - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

3.

ОглавлениеTUESDAY woke on the sofa,, blinking at the morning light, her shirtdress drenched in sweat. Scratching her head, which itched from the thick Aqua Net in her unraveling beehive, she stood and put her bare foot over the floor vent. She felt only a gust of tepid air. Twice in five days the air conditioner repairman had claimed to have fixed a Freon leak. She got a stomachache thinking of the expense of replacing the unit, and she began to list in her mind all the other fallibilities of her house. The unkempt branches of a tree would soon enough be scratching threateningly against the windows with any gust of winter wind. And the faulty wiring kept the house only halfway electrical.

This was something Tuesday did—she would stop a minute to concentrate on the most decrepit circumstances of her life. She’d close her eyes and immerse herself in the misery until she was druggy with unhappiness, until every obstacle seemed hazy with the impossibility of solution, and she’d drop, tired, into her sofa cushions. If it was just her, Tuesday wouldn’t care about a house hot like an oven. If she was all alone, all she’d need was a tiny corner of a cold-water flat.

When she opened the window to glance outside at the air conditioner, she saw a girl’s legs poking out from the thicket of mums planted alongside the house. Though the legs were long and thin, entirely un-Nina-like, Tuesday felt certain for a second that she’d just happened upon her daughter dead in the grass. Part of her had always been prepared for Nina to go suddenly and absolutely from her life. Some nights she’d be startled awake by the complete silence of the house, and she’d have to wake Nina with a soft shake and crawl into bed with her. Nina would stroke Tuesday’s hair and whisper-sing a new song she’d memorized.

A butterfly landed on the leg blotchy with sunburn, and the girl, not dead after all, slapped at the startlingly sea-blue bug as if it was as useless as a mosquito. Tuesday stepped outside. “Millie,” she said, seeing that the legs belonged to the girl who lived in the country but was always tumbling around town, the twelve-year-old with perpetually dirty knees who would sometimes sneak into the backyard to play with Nina and strip her Barbies naked. Millie wore a yellow tutu and ballerina slippers, and she lay next to candy spilled from a plastic, pumpkin-shaped bucket.

“Did you take Nina’s candy?” Tuesday said. She noticed Nina’s open window and recognized the bucket and its contents from when Tuesday took her trick-or-treating around the block before the costume party. Millie sat up then, her eyes heavy-lidded, her head bobbing on her neck. She seemed startled out of some stupor, looking all caught-in-the-act.

“Nina’s not in her room,” Millie said. Her skin was the white-blue of skim milk, her breath smelling slightly of chemicals. “This was on her bed.” She handed Tuesday a crumpled piece of paper, then stood, her tutu droopy, and stumbled away, nearly tripping over the loose laces of her slippers.

Before Tuesday even read the note, she knew it was from Hud, recognized the skinny, spiky letters of his serial-killer scrawl. Tuesday rushed to the open window, anxious to touch Nina, to feel Nina’s back minutely rise and fall with her slow breath as she slept so late. She reached into the window and, pushing at the empty puff of the goose-down duvet on the bed, she realized how easily any passing stranger could grab Nina by the hair and whisk her away with nothing much more than a flick of the wrist.

Deep in her heart, she knew Hud would never vanish with their daughter, though he wouldn’t be throwing away much of a life, as she saw it. All he loved about the town was the flea market on the courthouse lawn on Saturdays. Trashy teenaged girls gathered in the grass at the steps of the bandstand where he sat to play his guitar and sing the songs he’d originally written for Tuesday. Tuesday sometimes worked a face-painting table at the flea market, painting unicorns and daisies on the cheeks of the children, and these girls, their dirty hair stinking with smoke, would walk up in their ratty tube tops and request that Tuesday paint little hearts and daggers, or their boyfriends’ names in gothic letters, on their chests and skinny upper arms. They’d sit giggling as Tuesday worked her brush begrudgingly across their baby-pink skin, the girls tipsy off whatever soft booze—the melon liqueur or wine cooler—they drank from a lunch-box thermos, using a Twizzler for a straw.

When I get Nina back, Tuesday thought, picking up a Tootsie Pop from the ground, unwrapping it, and tapping it against her teeth, I’ll let her have the run of the place. She would let Nina drink Pepsi for breakfast, let her sleep naked in the sandbox. “Why would I go anywhere with you?” Nina would tell Hud as she painted her toenails any color, even a garish hooker-red.

I hate him, she thought. Walking quickly toward the town square, where the flea market would already be under way, she ducked the toilet paper hanging from some of the trees and twisting in the hot breeze like streamers. Even when she loved Hud madly, she would fantasize about his death. Maybe not fantasize, but she would imagine what it would be like. He put her through a lot, people would say, marveling at her stoicism, but she was so devoted. They’d all call her the Young Widow Smith and would feel a thump of sympathy when they’d catch sight of her in the months after, wearing sunglasses in the winter and polyester scarves over her hair, resembling Barbara Stanwyck on her way to an illicit encounter.

As Tuesday approached the courthouse lawn, chewing on the hard candy of the Tootsie pop, she saw that Hud’s small but regular audience had already gathered at the bandstand steps. One of the girls wore curlers and distractedly pulled at a piece of frayed thread at the edge of the American flag draped across a rail of the gazebo. “Where is he?” Tuesday asked, and the girl shrugged. This was the one who loved Hud the most—Tuesday had watched her once. She had rested her head on another girl’s shoulder as she listened to Hud sing. Later, she had come to Tuesday’s table and asked her to paint on her throat as many words as she could fit from the lyric, “I taste the tart wild plum on your lips,” which Tuesday knew from a song Hud had written about a summer afternoon they’d spent at a lake years before, back when they were a couple of love-struck babies.

“When he sings,” the girl had said as Tuesday painted, the stretched skin of her neck twitching as she spoke, causing the blue letters to smear, “his voice is so strong, I can feel it shiver my chest.” But that wasn’t enough for the girl. Tuesday could tell she was thinking deep by the way her tongue clicked a little, her whistle wet with more to say. “It’s so strong in my chest, he can change the beat in my heart, make it beat to the beat of the song.” Ridiculous, Tuesday thought. Hud’s singing voice was weak and full of cracks. It would break at a song’s most emotional moment, obscuring key words, sometimes obliterating all meaning.

“Have you seen Hud? Or Nina?” Tuesday asked Ozzie Yates, who sold peaches from the back of the pickup he backed up to the edge of the lawn. Tuesday and Ozzie were old friends, and Tuesday’s son, Gatling, had loved Ozzie’s daughter, Charlotte.

“No,” Ozzie said, winking, “I’ve not seen Hud. And I’m damn near close to tears about it.” Ozzie and Hud shared a notorious animosity for each other, a friendly hatred that bordered on the sexy. Ozzie, in his dirty, loose-fit Levis and Western shirt all unsnapped down the front of his hairy chest, had been the one she had imagined being alone with when she was still lying next to Hud every night, scheming ways to ruin everything.

Ozzie took a pale yellow, nearly white peach from a basket and held it to Tuesday’s cheek, touching the gentle fuzz to her skin. “How much for it?” she said. She took the fruit, running her thumb across its light bruises and its few patches of orange freckles.

“It’s on the house,” he said, and Tuesday smiled and walked away. Ozzie depressed her terribly sometimes, even when they just stood there negotiating the price of peaches. He’d once had a pretty wife who died of a swift illness, leaving him to raise Charlotte alone. Though Ozzie was not at all judgmental, she sensed something pleading in his wet eyes, like he wanted to scold her for so blindly letting her family fall apart.

Tuesday walked on down the rows of tables of castoff notions and novelties, still asking about Hud and Nina. She stopped at Lily Rollow’s table and dipped her fingers into the teacups full of jewelry. Lily and her sister ran an antique shop in the country; the sister, Mabel, gave better bargains. Lily was cranky—she was pregnant and freshly divorced and only twenty years old. She sat in a fragile-looking lawn chair with a broken weave, a handheld battery-operated fan blowing her bangs up. “Who are you supposed to be?” Lily asked.

Tuesday touched at her hair, remembering she was still in last night’s costume. “Catherine Deneuve in Mississippi Mermaid,” she said.

“You’re so funny,” Lily said with a chuckle.

People often said that to Tuesday. But Tuesday didn’t think of herself as funny at all, hadn’t told so much as a tired joke in years. “Yeah,” she told Lily. “I’m a regular Henny Youngman.”

If anything, she was completely unfunny. She used to be funny, but she hadn’t liked it. A woman wants to be thought mysterious and tragic. I cry my eyes out most nights, she wanted to object. I listen to Roberta Flack and get sauced on hard cider and conk out, useless, around midnight.

“It’s adjustable,” Lily pointed out as Tuesday watched the glass of a mood ring on her pinky cloud over from a peacock-feather blue. “Fifty cents.”

Tuesday wanted to buy the ring for Nina, but she only had a quarter in the pocket of her dress. As she dug for more change, her fingers ran across a few hexagonal happy pills the Widow Bosanko had pressed into the palm of her hand the other afternoon during Nina’s birthday party. She’d been carrying them around ever since. While a group of neighborhood brats had batted at a Raggedy Ann piñata, Hud had sauntered in holding a beer bottle at his side, with a girl’s rabbit-fur coat he’d ordered from a catalog. Nina had worn the coat outside all day, stumbling, nearly fainting from the heat, her fair hair dark with sweat. “Mother’s little helper,” the Widow had whispered, administering the pills to Tuesday in a handshake, the wooden cherries of her bracelet rattling.

Tuesday wanted to swallow the pills now, but she remembered how a psychiatrist had put Gatling on prescriptions once, mood drugs that made him dopey and sluggish and trembled his hands. But for a while it had been a relief having Gatling so docile and curled up on her sofa watching afternoon reruns of The Rockford Files and McMillan and Wife.

Lily accepted the quarter as payment for the ring, and Tuesday walked on to Hud’s building. The buzzer, she knew, didn’t buzz, so she picked up some crumbled pieces of brick on the sidewalk and tossed them up to tap against the upstairs windows. Where is my family? she thought, noticing her reflection in the window of the defunct shoe repair shop. She pulled the one remaining false eyelash from her lid, then ran her long press-on nails through her hair, combing out her beehive. When you’re all alone in the world, you only have yourself to worry about, she thought. But when you have people, their tragedies are your tragedies. Your potential for misery is doubled, tripled, quadrupled.

Then she looked past her reflection to the shoes that remained on a shelf. The shop owners had just up and closed one day, after committing their thirty-year-old autistic son to an institution. They retired to Oregon, leaving behind some repaired shoes still uncollected, others still unrepaired. Tuesday saw one of her own strappy sandals that she’d forgotten she owned. The thin black ankle strap that had broken loose was now perfectly reattached, and the shoe sat waiting to step off into an elegant evening, high-heeled and pristine, its toe scuffs polished away. It wasn’t the type of shoe she’d wear, so she hadn’t even missed it, didn’t even know where its match was. She’d bought the shoes a few years before, when she and Hud were trying to save their marriage. Every other weekend or so, they would dress up and drive to the casinos across the river from Omaha. While Hud played blackjack after dinner with loosened necktie, Tuesday, in her black cocktail dress, would sit alone at a table in the lounge sipping chocolate martinis and listening to a woman who impersonated Barbara Streisand, Tina Turner, and Karen Carpenter. Those evenings, Tuesday thought, weren’t as bad as they sounded. They were nice, actually.

Tuesday rubbed at the glass of her mood ring as she headed back home, hoping to work its mud-colored froth into a shade of pink. As she turned the corner onto her street, she slowed her steps, giving Hud a better chance to sneak Nina back into her bed. Ghosts knotted together from pillow cases hung from porch eaves. A scarecrow, its stuffing beaten out of it, lay in a heap in the middle of the street.

In her driveway now were her father’s Caddy and her sister’s VW bug. When she saw Mrs. Katt, the neighbor, walk up to the porch, she began to panic. Mrs. Katt would show up at any moment of despair with a can of Folgers, and she’d scrub your kitchen while you convalesced with your family in another room. You’d sit in your pajamas, you’d play rummy, waiting for some news or some fever to break, and become somewhat eased by the heavy scent of cinnamon as Mrs. Katt heated an offering in the stove. Tuesday had a cupboard full of Mrs. Katt’s plates and tureens she needed to return, all with the woman’s name on a piece of masking tape on the bottom.

Tuesday quit worrying when she heard the loud discord of the out-of-tune piano as somebody tumbled their fingers across the keys. Hud was the only one who ever played the piano, which had been shoved onto the screened-in back porch, and she began to hear his voice rising above the whir of the broken air conditioner. She didn’t want to be, but she was glad to hear him singing in her house. She thought of one beautiful song Hud had played for her on the piano on a wet October night. As the rain tip-tipped against the screens, she rocked a sleeping Nina in the old chair they’d had since their first apartment. The joints of the rocking chair squeaked and quivered, and Hud sang softly a song he made up on the spot, about what it felt like to dream at night about a girl like Tuesday.

Pressing her forehead against the screen of the porch door, Tuesday watched Hud entertain her father and the Widow and her older sister, Rose, named for the shock of her father’s red hair she’d been born with, and Mrs. Katt. They all stood or sat sipping coffee from Tuesday’s best cups, swaying to Hud’s song, which seemed to be about a brokenhearted father putting his children to bed. Rose and Red sat in the nearly wrecked wicker chairs, small plates of Mrs. Katt’s crumb cake balanced on their knees. Everyone’s eyes were on Nina, who did an interpretive dance in the middle of the small room, just behind the piano bench. Nina linked her fingers above her head, closed her eyes, and turned on the ball of one foot in an approximation of a pirouette. She then quickly and awkwardly moved into a jazz singer’s slo-mo hip shimmy and snaked her arms around in front of herself. Nina’s dancing was silly and pretty all at once, and Tuesday closed her eyes, mesmerized by her daughter.

Then Nina screamed, startled out of her hypnotic dance by the sight of Tuesday’s dark shadow at the screen. Nina stood there, both hands tight at her mouth. Hud stopped playing, and everyone looked, alarmed, toward the door.

“Mommy!” Nina said when she realized it was only Tuesday. She ran to the screen and opened it, then hugged Tuesday’s legs. “Oh, you won’t believe what happened,” Nina said, speaking in a rush. “It’s not Daddy’s fault, really it’s not,” she said. “Really it’s not. The car. It’s the car’s fault. The car just up and took a shit on him.”

Tuesday finger-thumped the top of Nina’s head. “You know I don’t want you talking like that,” she said. She looked around the room as everyone avoided her eyes. They looked into their coffee cups, or out the windows of the porch, suddenly embarrassed for having enjoyed Hud’s company. Hud just sat hunched at the piano, pushing down slowly on this key, then that, making no music. Rose pinched at a run in the ankle of her stocking. Stockings, thought Tuesday. Now, how about that. Practically crack-of-dawn Saturday morning and there she sits in pricey shoes and her best light-yellow summer dress. Rose always did have a thing for Hud. Tuesday could smell the stench of Rose’s perfume, some designer knockoff she ordered by the vat on the Internet.

“Honeycomb,” Tuesday said to Nina, bending over to kiss the top of her head, “would you go to your room and wait for Mommy? I’ll be in in a minute to tell you how much you worried me.”

“OK,” Nina said, walking away with her head lowered.

“So how’d everyone hear about Hud’s little party this morning?” Tuesday said. “His little party here in my house?”

“We were up at the flea market,” the Widow said. “People said your hair was a mess and you were looking for Nina.”

“Don’t make a federal case, Day,” Rose said, sharing a smirk with Hud and crossing her legs. “Everything’s fine.”

“You stink,” Tuesday said, feeling mean toward everyone there. “Where the hell did you get that cologne? Truck stop?”

“Oh, girls,” Red said. “Let’s be sweet.”

Rose laughed through her nose, rolled her eyes. “Shows you how much you know,” she said. “It’s Shoot the Moon you’re smelling.”

“Oh, is that what that is?” the Widow said, clearly impressed. “I thought maybe that’s what.”

“Got it at Marshall Field’s that last time in Chicago,” Rose told the Widow, uncrossing her legs, then recrossing them. “I’ll get you some the next time I go back.”

“Oh, honey, I’d kiss you all over,” the Widow said.

Rose would never have paid the $100 a bottle for Shoot the Moon, Tuesday knew. She probably just tore an ad from a fashion magazine and rubbed the scented page against her throat in the car on the way over.

When Hud began tapping out “Chopsticks” on the piano, Tuesday reached over to slam down the lid over the keys. Hud snapped his hands back just in time and jumped at the loud noise of the fallen lid. “Damn, Day,” he said, looking up at her with that baffled, what-the-hell-did-I-ever-do-to-you? look he’d mastered years before. With that look, so carefully maneuvered he must have practiced in a mirror, he always effectively made Tuesday feel like the biggest bitch that’d ever walked upright. In his lovely blue eyes, with that look, were kindness and a boy’s gentle confusion. Gatling had inherited Hud’s counterfeit innocence, had started working that same look way too young.

“One of these days I’ll run away with her myself,” Tuesday said, remembering the peach in her pocket. She pulled it out and pressed at a soft part of the fruit, trying to keep from crying again. “I’ll drop a match on this whole house of sticks as I leave. You’ll lose everything. The piano, your songbooks, all the crap you left behind. And we’ll be nowhere to be found.”

“You were just inches from setting the place on fire last night,” Hud said, whispering just loudly enough for everyone in the room to hear. “You had fallen asleep with a cigarette still smoking, burning a hole in the sofa. Who knows how big a fire you would’ve made if I hadn’t shown up? I, for one, don’t particularly want a little burn victim for a little girl.”

“Cigarettes,” the Widow Bosanko said, sighing, shaking her head. Mr. Bosanko had died of lung cancer.

Tuesday put the peach back in her pocket and left the room. She didn’t feel on the verge of tears anymore. Hud always took an argument just one step too far. He could so easily have her in the palm of his hand, right there along with Rose and the Widow, but then he’d say something too godawful. If he’d just left it at “Who knows how big a fire . . .” But then he had to turn Nina into a burn victim, erasing away all her darling features, her tiny, perfect nose and soft lashes and those lips of pale, pale pink.

In the bathroom she took off her dress and leaned her head over the side of the tub to rinse out her stiff hair. When she turned the water off, she heard that Hud had gone back to performing the rest of his song. Tuesday wrapped her wet head in a towel, stepping into the hallway wearing only the matching silk bra and underwear patterned with blue bunnies that Rose had given her last Christmas.

After pulling on a short tartan skirt and a t-shirt and grabbing her face-painting kit, Tuesday went to Nina’s room. Nina sat on the bed dressing her paper doll in a paper ball gown, and Tuesday sat beside her. She touched the fringe of Nina’s faux-leather vest. “You can wear this today too if you want,” Tuesday said.

“Good,” Nina said.

“Don’t ever leave me in the middle of the night, please,” Tuesday said. “Not even with your father. He’s full of evil schemes. I hate him.”

“No, you don’t,” Nina said, taking the tiny comb from her plastic purse, then running it through Tuesday’s hair.

“Yes, I do. Ouch. My hair’s all snaggy.” She took the comb from Nina and did it herself. “I hate him, and so will you someday. And you’ll hate me too, someday, I suppose.”

“No, I won’t,” Nina whined, scrunching up her nose and chin with offense. “You don’t know.”

Tuesday lifted the torn screen of the window. “Let’s go,” she whispered, and together they crept out onto the lawn as Hud got to an emotional part of the song that involved a kind of pained bellowing. Tuesday lifted Nina into the handlebar basket of her bicycle, hooked the face-painting kit to the back, and rode away, the bike shaky on its wheels. Nina sat high in the basket in her cowgirl suit, the fresh peach cradled in the cup of her two hands.