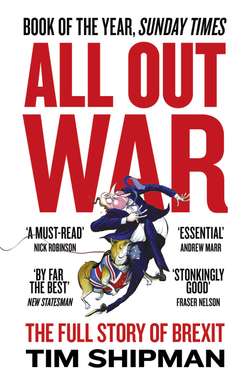

Читать книгу All Out War: The Full Story of How Brexit Sank Britain’s Political Class - Tim Shipman, Tim Shipman - Страница 18

Stronger In

ОглавлениеAndrew Cooper listened to the answers, made careful notes, and tried to remain positive. It was difficult. A thickset, balding man with hunched shoulders, it was said even by friends that he often appeared ‘the most lugubrious man in the room’. In more than two decades as a pollster, and as one of the chief architects of David Cameron’s modernisation of the Conservative Party, Cooper had overseen some pretty difficult focus groups – but these were not giving great grounds for hope to the embryonic EU ‘In’ campaign Cooper had been hired to help.

It was April 2015, just before the general election, and Cooper had seen the same warning signs in his polls. Sitting down with Peter Mandelson, the leading public relations executive Roland Rudd, Rudd’s chief sidekick Lucy Thomas, and Susan Hitch, who worked with David Sainsbury, the millionaire former Labour donor, he took them through the evidence. His message was simple: Britain was much more Eurosceptic than they had feared.

‘What we found was this very hard set view about why our hearts say we don’t like the EU and why we should leave it,’ Cooper said. ‘One, it costs a bloody fortune. Two, immigration: migrants coming here and taking our jobs and our benefits, putting pressure on our services. Three, it meddles in our lives in ways which we didn’t have before. The first two were much more important than the third.’ But here was the kicker, the real punch in the guts for a pro-European like Cooper: ‘Then you say, “OK, that’s what you don’t like. What are the positives?” And you’d usually get silence.’ The focus-group members would look at each other sheepishly, and someone would say, ‘Well, there’s the trade …’ But Cooper could tell their hearts were not in it.

After a month of work he outlined the headline voting figures. The raw statistics showed ‘Yes’ to Europe beating ‘No’ by 53 per cent to 47 per cent. But when he factored in differential turnout – the effect of passionate Eurosceptics being more likely to vote – the result was a virtual dead heat: 50.2 per cent for ‘Yes’, 49.8 per cent for ‘No’.

Lucy Thomas was usually a cheerful soul. A former BBC reporter in Brussels, she was campaign director of Roland Rudd’s pro-EU outfit Business for New Europe when the small team began putting together a prototype ‘In’ campaign. But even she struggled on the day she watched Cooper’s presentation. She thought to herself, ‘Oh God, this is going to be a lot harder than we thought. There was no sense of what the positives were.’

‘They all thought it was a more challenging picture than they had hoped for,’ Cooper said. ‘Underlying attitudes were very sceptical.’

Cooper had been approached in February by Susan Hitch, who remembered his role on Better Together, the cross-party campaign that had helped to win the Scottish independence referendum the year before. In March 2015 Thomas hired Cooper’s company, Populus. His first task was a ‘segmentation analysis’, dividing up the country into different groups of voters based on their attitudes to Europe. ‘You’re really trying to dig into people’s deeper feelings,’ he says. ‘So rather than just asking about a referendum directly, you’re trying to get a sense of their worldview and their feelings about multiculturalism, globalisation, engagement with other countries, their sense of optimism/pessimism. What the segmentation poll does is trying to get beyond the headline poll position to a deeper understanding of the country’s attitude.’

By 15 April Cooper had found six attitudinally similar groups, given them names and constructed a profile of each one, complete with a picture of a typical member. He found that two groups – ‘Ardent Internationalists’ and ‘Comfortable Europhiles’ – accounting for 29 per cent of the population, were almost certain to vote to stay. A third, much smaller group, ‘Engaged Metropolitans’, was also overwhelmingly for Remain, and was very active on social media.

Cooper identified two resolutely ‘Out’ groups. ‘Strong Sceptics’ were almost entirely white, likely to be aged over fifty-five, from the C2DE social bracket and with only a secondary education. They were often Labour voters flirting with Ukip, and made up 21 per cent of the population. The ‘EU Hostiles’ were typically retired, living mortgage-free on a private pension, and supporters of Ukip who got their news from the Daily Mail. They made up 11 per cent.

For Cooper, the battleground would be over the other two groups. The ‘Disengaged Middle’ were typically in their thirties, relatively well-educated, middle-class, but not at all interested in politics. They knew almost nothing about the EU, and did not feel it had much to do with their lives. Seven out of ten in this group got their news from Facebook. The final group, who encapsulated the rhetorical challenge the campaign faced, were christened ‘Hearts v Heads’. They were two-thirds female, more likely to be in late middle-age, married or divorced with children, working in a low-paid job or part-time. They were disproportionately likely to have left school aged sixteen, and to be struggling to make ends meet. They read newspapers and were interested in the issue of Europe, but found it very confusing, and felt conflicted. Over 80 per cent of them agreed with the statement ‘My heart says we should leave the EU, but my head says it’s not a good idea.’ In the Scottish referendum, Cooper had had an identical segment which had helped Better Together to victory. In his April 2015 survey, ‘Yes’ led ‘No’ 55–45 among the two groups of key target voters. From that point on ‘we only did focus groups among those two groups,’ Cooper explained. Success depended on holding on to that lead.

The Remain campaign had no name, no strategy and no message, but when David Cameron secured his surprise majority at the general election the handful of people involved did know their target voters, and had enough data to begin constructing a plan. On election night Rudd threw a party at Villandry, a restaurant in London’s clubland. When it became clear that the Tories were on course for victory, Lucy Thomas approached him and said, ‘It’s on. It’s happening.’ They both had another drink. All they needed now was a leader, a headquarters, and a proper organisation.

The outfit Cooper had signed up to was the third effort at creating a Remain campaign. The three driving forces were Peter Mandelson, the former EU Trade Commissioner and one of the founding fathers of New Labour; David Sainsbury, the Blairite peer and former Labour Party donor; and Roland Rudd, a debonair fifty-four-year-old who had founded Finsbury, one of London’s powerhouse PR outfits. He had argued for years that Britain ‘should lead not leave’ the EU.

First Mandelson and Rudd had sought to empower an umbrella group called British Influence, run by Peter Wilding, a veteran of the EU battles of the 1990s. They then shifted resources to the European Movement, run by the former Tory MP Laura Sandys. Mandelson recalled, ‘We had two false starts on the pro-European side funded by David Sainsbury. One was British Influence, of which I was joint president with Ken Clarke and Danny Alexander, which was established long before the 2015 election and was hopelessly run. The other initiative, after the election, was led by the former Tory MP Laura Sandys, which didn’t come together. David then asked me to convene a viable campaign, which I did along with Damian Green and Danny Alexander during the summer of 2015. David paid all the startup costs. It would not have happened without him.’

Green, a Conservative former immigration minister, said the British Influence effort ‘didn’t work because it was basically run by elderly grandees who weren’t going to get their hands dirty. David Sainsbury said, “We need people who’ll actually do things.”’ Mandelson and Rudd recruited Will Straw, the thirty-five-year-old son of the former Labour foreign secretary Jack Straw, to run the operation. He had just fought the Lancashire seat of Rossendale and Darwen at the general election, but lost to Jake Berry, the sitting Conservative MP, by more than 5,000 votes. But Mandelson saw a bright and organised young man with politics in his blood, who was good with people and pleasantly devoid of the ego that afflicts so many in politics. He correctly judged that Straw could build a team. Straw’s experience in Lancashire was also useful, because Ukip had won almost 7,000 votes in the constituency, and he was familiar with the issues that motivated Eurosceptic voters.

Shortly after the election Lucy Thomas recruited David Chaplin, an adviser to Douglas Alexander, the former Labour frontbencher, to help with the media operation. Softly-spoken but fiercely intelligent, Chaplin was one of the sharpest of a group of Labour aides who were now looking for work. With his sardonic sense of humour, he became the campaign’s weary voice of reason when others indulged in flights of fancy.

Mandelson also emailed Ryan Coetzee, a nuggety forty-two-year-old South African political strategist with a closely trimmed goatee beard who had run the Liberal Democrat election campaign. The Lib Dems had been virtually wiped out in May, losing all but eight of their fifty-seven seats, but Coetzee was a tough pro who understood strategy, polling and message development. He was also used to adversity, having masterminded three election campaigns for the liberal South African party the Democratic Alliance, in an even more hostile electoral environment. In early July Coetzee went to Mandelson’s Marylebone offices, where the peer ‘interviewed me and I interviewed him’. After the wounding experience of the general election Coetzee ‘wasn’t particularly sure I wanted to do it’. But by the end of the conversation, he said, ‘We both concluded it would be quite a good idea.’ Mandelson said, ‘Great! Come into the room and meet all the others.’ They walked next door, to find Will Straw, Lucy Thomas and Andrew Cooper waiting.

On Friday, 3 July 2015 Straw organised a meeting at Mandelson’s office with the three politicians – Mandelson, Green and Alexander – plus Rudd, Cooper, Lucy Thomas and Greg Nugent, the marketing expert who had won plaudits for his work on the branding of the London 2012 Olympics, and had also assisted the Better Together campaign in Scotland. The advertising agency Adam and Eve had done some work on what to call the campaign, and some ideas for logos, but Straw did not regard these as ‘up to scratch’, and as a result of the meeting North, another ad agency, was recruited. They devised the iconic red, white and blue Britain Stronger In Europe logo.

‘You’d have these long meetings where you over-intellectualise a small number of words and colours,’ Straw said. The idea had been that they would abbreviate the title to ‘Stronger In’, but the full name was the product of market research. They wanted to appeal to the patriotic vote, so ‘Britain’ was important, along with the red, white and blue colour scheme. ‘Stronger’, the most important word in the name, tested well in Cooper’s focus groups. They considered just calling the campaign ‘Britain Stronger In’, but as Straw explained, ‘If you didn’t mention Europe at all then people might have thought you were for the Leave side, people wouldn’t know what we were for.’

Straw insists he was aware that their opponents would shorten the name to ‘BSE’, the acronym associated with ‘mad cow disease’ in the 1990s, one of the most difficult periods of UK–EU relations: ‘We did discuss the BSE acronym. We went in with our eyes open.’ Cummings, Stephenson and Oxley would regularly refer to Stronger In as ‘the BSE campaign’, but Straw is adamant that the problem was not the acronym, but that ‘in the end control rather than strength was what people wanted’.

In July, conscious he was running a Labour-heavy team, Straw approached Tom Edmonds and Craig Elder, who had run the Conservatives’ digital team during the general election, and asked them to join Stronger In. Another recruit was Stuart Hand, the Tory head of field operations. He was the man who had trained up Tory organisers to fight the so-called 40–40 marginal seats on which the Conservative majority was built. One of those constituencies was Rossendale and Darwen, where Hand’s efforts had helped to stop Straw himself becoming an MP. When Straw interviewed Hand they shared a ‘wry joke’ about his Conservative opponent Jake Berry.

To run the campaign’s outreach work with businesses and celebrities Straw brought in Gabe Winn, an executive from the energy giant Centrica. Winn was a personable and shrewd operator who was well plugged in to the Westminster world through his work and his brother Giles, a political producer with Sky News. The two had long joked about forming a public-affairs agency called ‘Winn Winn’. Gabe hoped his move into politics would be just as successful.

Having got the nucleus of a campaign team together, the former political rivals gathered for an awayday at the Village Hotel in Farnborough. It went well. A sense of camaraderie developed. The only fly in the ointment was that David Cameron and George Osborne did not want the campaign set up at all. Mandelson had seen Osborne at the Treasury after the general election, and had reassured the chancellor that the campaign would be created in ways that were friendly to the government, allowing Cameron to take over its political leadership when the time came. At that stage Osborne had seemed relaxed. He even joked that he expected the campaign to be a full-on ‘New Labour-style operation’.

Things changed towards the end of July, when Mandelson met Cameron at a leaving party for a Number 10 official. The prime minister was distinctly cooler, and complained that Mandelson’s actions were premature, that the creation of the campaign would annoy the Tory Party, appear to pre-empt his negotiations in Europe, and even undermine them. He made clear his concern that a campaign run by all the pro-European ‘usual suspects’ would be counterproductive. In September he sent the same message to Mandelson via a mutual friend, urging him and the others to ‘back off’.

In further conversations Osborne explained that the government, which was holding open the at least theoretical possibility that it might campaign to leave, couldn’t just sign up to a pro-European campaign. Privately he thought Mandelson and co. were ‘unrealistic’ because they wanted ‘full government involvement’ even at this early stage.

Mandelson stuck to his guns, explaining to both the prime minister and the chancellor, ‘I have directed or chaired three general election campaigns, ’87, ’97 and 2010, and I know what’s involved. You cannot create a national campaign from a standing start a couple of months before polling day, especially when you are having to counter twenty years of relentless anti-European propaganda in Britain.’

Damian Green also went to see Cameron after the election, but told colleagues ‘it wasn’t a meeting of minds’. Green argued that there would be a need for a ‘pro-European Conservative voice in this debate’, but felt the prime minister had only seen him ‘out of politeness’, and nothing came of the meeting.

Straw tried to smooth things over, going for a pint with Daniel Korski, the deputy head of the Number 10 policy unit, who advised Cameron on EU affairs. ‘They felt that it wasn’t inevitable that we would become the designated campaign,’ Straw recalled. Indeed, Korski was arguing internally that the Tories should set up their own, separate, campaign. As late as November 2015 he and Mats Persson, the former head of the Open Europe think tank who had been recruited by Number 10, offered to leave and set one up. They suggested that Open Europe itself might be converted into a campaign vehicle.

‘The problem was that Cameron did not accept that an all-party campaign was needed,’ said Mandelson. ‘Early on he let it be known to people like Ken Clarke that he didn’t intend to run it that way. But Cameron had not thought this through. He was thinking in Tory Party terms, assuming that the voters would follow him as prime minister and party leader when the time came. He also didn’t appear to understand his own legislation, which required a designated campaign on the Remain side to reflect cross-party opinion.’

The prime minister’s attitude would shape his approach to Stronger In throughout the short campaign, when key decisions continued to be made in Downing Street, rather than at the campaign’s headquarters in Cannon Street. The most serious immediate impact of Cameron’s disapproval was that donors and businesses were deterred from signing up. A senior figure in the campaign said, ‘They very actively told businesses not to cooperate, saying it would be regarded as a hostile act inside Number 10, so the campaign didn’t have the ability to get people lined up.’

In accounts of this period in the press, the finger of blame has been pointed at Korski, the point man in Number 10 for many businesses. Korski says this claim is ‘a total fantasy’, and denies that he was proactively calling anyone. Instead, businesses called him after Sajid Javid, the business secretary, addressed the CBI on 29 June 2015 and rebuked the organisation for its pro-EU stance. Korski told those who rang him, ‘It’s not for me to tell you what to do. You’ve got responsibilities to shareholders, to staff.’ He did not tell business leaders to say nothing. But he did advise some of them, ‘If you’re a very rich oil company with most operations outside the UK, or a tax base that’s structured in a way that means you’re not domiciled, think carefully about whether you have a legitimate voice in this debate.’ To those who wanted to help Cameron he suggested, ‘It’s obviously better to say that you want to reform Europe, because if you say you want to stay in, then you’re going to expose yourself to people who say, “You don’t have a legitimate voice because you’re a billionaire.”’ It is easy to see how this friendly advice might have deterred some from putting their heads above the parapet.

Roland Rudd, who ran the initial fundraising operation, achieved a breakthrough when he began approaching investment banks. He managed to get donations from Goldman Sachs, and that opened doors at JP Morgan, Morgan Stanley and Citibank. Rudd raised £1.5 million that way, and another half a million from ‘big chunky donors’ like Ian Taylor, Lloyd Dorfman and Andrew Law. Andrew Feldman, the Conservative Party chairman, got David Harding, a billionaire financier, on board. He became the treasurer. In the end, most of the financial support came from Conservative donors.

Over the summer and into the autumn, Ryan Coetzee worked with Andrew Cooper to draw up Stronger In’s strategy. By the end of November he had completed the campaign ‘war book’ and ‘messaging bible’. ‘If you’ve not written it down, it’s not a strategy,’ Cooper said. ‘The war book is everything we know: the segmentation, our strongest messages, “This is our message in a sentence”, “This is our message in a paragraph”, “This is our message in a page”, media strategy, campaign grid. That’s the Bible.’

The goal was to target the two persuadable groups, the ‘Hearts v Heads’ and the ‘Disengaged Middle’. Cooper conducted regression analysis, a statistical device to estimate the relationship between variables, and discovered that both groups were susceptible to arguments about economic risk. Coetzee said, ‘The two in-play segments in the middle believed it was riskier to leave than it was to stay. And when you look to the regressions, you found that the risk question was really driving the voting intention responses.’ That appeared to be proof that Remain’s target voters were not just concerned about economic risk, they were prepared to change their vote as a result.

Coetzee also accurately predicted what they would be up against. Even before Vote Leave had published its ‘Take Back Control’ slogan, Straw said, ‘Ryan put together what he thought their script would be, and control was right at the heart of it.’ Coetzee also spotted where Cummings would hit them hardest: ‘Immigration, sovereignty and cost – those were the three we identified as our biggest weaknesses,’ said Straw.

To help draw up responses, Cooper and Coetzee conducted big ‘deliberative’ focus-group sessions, with six tables of ten people being quizzed simultaneously on every aspect of the campaign. The sessions, effectively six focus groups at once, lasted seven hours. ‘We did that in October and again in February,’ said Cooper. ‘You take them through: we say “this”, they say “that”. Say what our rebuttal of that point is. “What do you say now?” We’re playing clips of people, to test precise messages. We’re giving them new material, campaigning literature, graphics. That hugely enriched the campaign planning.’

The campaign had also acquired a base, though not an ideal one. Straw rented offices at 14 Dowgate Hill, fifty yards from Cannon Street station. The rather poky suite featured a main meeting room so small that only eight people could sit comfortably around the table, and a spillover basement room known as ‘the bunker’, situated incongruously between an agency for film extras and a Botox clinic, whose facilities were used by at least one campaign staffer.

Before Stronger In could launch, it needed a board and a chairman to front the campaign. Mandelson and Rudd wanted someone with a business background – ideally a Tory woman. Damian Green recalled, ‘The fear was it would look like a New Labour rump, and we were very keen that shouldn’t happen.’ Karren Brady, the West Ham United vice-chairman and star of The Apprentice, was approached, but she declined. Carolyn McCall, the boss of EasyJet, also turned the job down. ‘Serving CEOs found it much harder to take on an additional task,’ Straw recalled. The leading contenders were Richard Reed, the founder of Innocent smoothies, and Stuart Rose, the former chairman of Marks & Spencer, who Cameron had let it be known was his preferred option. The main attraction of Rose was that he had previously been a supporter of Matthew Elliott’s Business for Britain, and that meant his recruitment could be presented as a defection.

Lucy Thomas said, ‘Stuart was exactly what we needed as chair to make the pragmatic, reasonable and patriotic case. He’d run one of the best-loved British brands, and had a reputation for being a highly successful businessman as well as a nice, decent bloke. He was also a Eurosceptic who was rightly critical of the way the EU worked and in favour of significant reform.’

The only problem was that Rose, while happy to join the board, did not want to be chairman. Straw and Coetzee visited him in late September, and he said ‘definitely, categorically’ that he would not do it. Rudd received the same message. But Rose was finally persuaded by a barrage of calls virtually on the eve of the launch in early October, including one from George Osborne. Rose said, ‘My first judgement was no, my second judgement was no, my third judgement was no – and then I failed to listen to my judgement. I was a square peg in a round hole.’ ‘On the Friday before the Monday launch, they didn’t have a chairman,’ a senior Tory said. ‘George got him to do it. But that was very late in the day, and it meant he had almost no time to prepare or be briefed, which is why he didn’t perform brilliantly at the launch.’

That was putting things mildly. Even before he spoke, Vote Leave’s researchers had dug up comments Rose had made in April dismissing fears that leaving the EU would cause companies to quit the UK as ‘scaremongering’. The night before the launch, the campaign briefed Westminster journalists that Rose would use his speech to dismiss those backing Leave as ‘the Quitters’. But when he spoke on Monday, 12 October he refused to use the phrase, rendering every morning newspaper’s story inaccurate. Rose recalls: ‘I let myself down. I’m not used to being given a very closely drafted brief. I’m used to interpreting things in my own way.’ If the press pack was unimpressed by that, their ire was greatly increased when Rose refused to take any media questions. The location of the launch, a former east London brewery, made the job of the parliamentary sketch writers too easy. References to Stronger In’s failure to organise a piss-up in such an establishment abounded in the following day’s papers.

To compound the problem, Rose then gave an interview to Rachel Sylvester and Alice Thomson of The Times in which he admitted, ‘Nothing is going to happen if we come out of Europe in the first five years, probably. There will be absolutely no change.’ Steve Baker emailed the Eurosceptic MPs to say, ‘We should make Lord Rose an honorary vice president of Conservatives for Britain. There is no truth in the rumour that the noble lord is a CfB infiltrator, notwithstanding the evidence to the contrary.’ Rose’s reputation as a gaffemeister supreme was set, and he enhanced it in January 2016 when he did a pre-interview soundcheck for Sky News and forgot the name of the campaign. Footage emerged of him saying, ‘I’m chairman of Stay in Britain … Better in Britain campaign … Right, start again. I’m Stuart Rose and I’m the chairman of the Better in Britain campaign … the Better Stay in Britain campaign.’ During the campaign he would tell a Commons Select Committee that Brexit would cause wages to rise. Afterwards, he felt ‘battered and bruised’ by the experience.

Lucy Thomas did not feel the Stronger In team could criticise Rose, who had had no yearning for the limelight, and was only doing the job ‘as a favour’: ‘As with any successful business person doing political campaigning, it’s really hard. You’re used to answering factual questions about your business, not tricky political issues. So you answer what you’ve been asked directly, but don’t realise that how it is interpreted might trip you up.’ A politician involved with the campaign was less understanding: ‘You hear business people say things like, “Why aren’t politicians like us?” Well, business people discover that politicians have craft skills as well, like not saying stupid things while on public platforms.’ Rose was a good chairman, however – ‘consensual and encouraging’, according to Mandelson.

Nevertheless, to have the front man neutralised so quickly made it difficult for Stronger In to build public momentum.

Lining up Tory board members was no simpler than locating a chairman. In the summer Mandelson called Ruth Davidson, the Tory leader in Scotland and one of the party’s brightest hopes, to see if she would join. As someone who wanted to be as good at politics as she could be, Davidson saw the opportunity to learn from Mandelson as great ‘career development’. But after the Better Together campaign, she realised she could not both campaign for Stronger In and fight the Scottish elections in May. She told Mandelson, ‘I’m really sorry, mate. I’ve got a really big election coming up. This could be a breakthrough election for the Conservatives in Scotland.’ She said later, ‘Having been part of Better Together, having seen how much it saps out of you, I just didn’t have the capacity for it.’ In the event, Davidson would secure a breakthrough, beating Labour into third place. Her chance to play a role in the referendum would come later.

The full membership of the Stronger In board was designed to show breadth and experience, bringing together the political, business, education, culture and military establishments. At its furthest extremes it included General Sir Peter Wall, the former chief of the General Staff, and June Sarpong, the former MTV and T4 presenter who is now a panellist on ITV’s Loose Women. Both Karren Brady and Richard Reed agreed to serve. In addition it was announced that the three living former prime ministers – Sir John Major, Tony Blair and Gordon Brown – plus Sir Richard Branson, Britain’s best-known businessman, were also supporting the campaign.

The Rose débâcle suggested a need for a stronger media operation. In the autumn David Chaplin, who had been handling most of the story briefing with the lobby journalists, wrote a memo recommending that Straw bring in a heavy hitter to be the campaign’s mouthpiece, allowing Chaplin himself to step back and do what he was best at, planning coverage over a longer period. From the beginning the campaign had one person in mind who was battle-ready to take on Vote Leave’s Paul Stephenson.

James McGrory was educated at an independent school, but you would never know it. A rake-thin, ginger-haired mockney bruiser, he loved playing football and deploying sporting analogies in his attack quotes. He combined acute news judgement with an irrepressible thirst for placing stories (and not a little ability at the bar), plus the respect of Westminster journalists. For five years as Nick Clegg’s spokesman he had ably fought the Liberal Democrat corner against newspapers which preferred to ridicule his boss. He never took anything personally, despite caring more than most about his cause. While others dealt with the Lib Dem wipeout at the election with alcohol and new careers in public affairs, McGrory disappeared to lick his wounds. Lucy Thomas first tried to sign him up in May. ‘I was not in a frame of mind to get back into a campaign,’ he said. But when Will Straw called later that summer he realised, ‘This is the fight of your life – it was quite an easy decision in the end.’

McGrory’s return to SW1 was greeted with mouthwatering expectation by those who had dealt with him before. The referendum would pitch two of the best spin doctors of their generation against each other. Both McGrory and Stephenson went into the tackle with their studs showing. To use an analogy about the Premier League’s two greatest hardmen, which McGrory himself had sometimes deployed when discussing alpha-male journalists, it was ‘a case of Keane against Vieira’.

McGrory joined at the start of December 2015. ‘James added a huge amount of professionalism and energy,’ says Chaplin. ‘He was not willing to let anything go, he had fire in his belly for the smallest story, and was exactly what the campaign needed. For James it was personal and professional. He wanted to win, and he believed in it.’ Lucy Thomas called him a man ‘with the mouth of a football fan and the heart of a true sandal-wearing liberal’. McGrory saw his brief as to ‘dial it up a couple of notches’. He soon did. They noticed at Vote Leave: ‘We thought their press operation improved dramatically,’ said Rob Oxley. ‘Suddenly we started taking a bit of fire.’

McGrory’s appointment meant Stronger In were ready to go into battle. Downing Street now had to decide whether they wanted to share a trench with them.

During the autumn Cameron remained ‘very nervous about any contact with the campaign’, Straw recalled, but clandestine meetings had begun with senior figures from Downing Street. The most important came on 26 October 2015, since it decided whether there would be a campaign at all. Straw, Coetzee, Thomas and Mandelson met Stephen Gilbert at Mandelson’s offices in Marylebone. Gilbert was joined after a while by Craig Oliver, Cameron’s spin doctor. ‘They were coming to check us out,’ says Coetzee.

Straw took the Tories through the organisational structure of the campaign and the relationship with the board. Coetzee gave a presentation on strategy, messaging and the progress made with building a predictive model for targeting voters. Thomas ran through the media plans. Straw said, ‘We brought them up to speed with where we were with the organisation, how we were building a nationwide campaign, all the recruitment we’d done, where we’d had some blockages, where we needed their help recruiting Conservatives.’

Top of the list of Stronger In ‘asks’ was help in hiring Jim Messina, the wizard of target-voter modelling in both Barack Obama and David Cameron’s re-election efforts. Roland Rudd had been briefing journalists since June that he wanted to recruit the American, but Messina had played hard to get. Coetzee had approached another set of US strategists, Civis Analytics, a New York firm founded by Dan Wagner, a Messina protégé from Obama’s 2012 campaign. The talks had got as far as a draft contract.

Coetzee had spoken to Cooper and said, ‘Andrew, the clock is ticking, because it takes time to put this stuff together.’ To get maximum value from voter-targeting data the campaign wanted to use it to send out leaflets and emails before the regulated spending period kicked in on 15 April. After that they would only be allowed to spend £7 million on their campaign. The trigger for the meeting was a warning from Cooper to Downing Street that the campaign had been ‘freaked out’ by Messina’s refusal to engage. Straw said, ‘We basically got to the stage where if Messina wasn’t going to work with us, then we needed to crack on with someone else.’

Gilbert and Oliver both began the meeting sceptical about joining forces with Stronger In. They both left believing they could do business together. Crucial to winning over the Conservatives was Coetzee’s description of the target voter as someone who was a persuadable Eurosceptic, rather than an enthusiast for Brussels. ‘I think their anxiety was, “Are these guys a bunch of Euronuts?”’ Coetzee said. ‘We understood that the marginal voter was concerned about the economy and immigration, and needed a “hardheaded case”. It was immediately apparent to everybody that we were all speaking the same language.’

Gilbert told Coetzee months later, ‘Our default position was “No”. Our default was “Yes” after the meeting.’ Craig Oliver’s view was that there were benefits to the cross-party effort. ‘Serious consideration was given to setting up another campaign,’ a senior Downing Street source said. ‘The danger would be that we would lose any contact with the other political groups that wanted to remain – and it would be seen as a Tory-only Remain vehicle.’

Straw recalled, ‘I think what they realised from those meetings was that we were serious, professional, we had a proper plan in place and we were in a position to fight a referendum.’ Crucially, the Tories were prepared to put the call in to Messina. Coetzee said, ‘We got the Messina show on the road, but frankly months later than it should have been.’

Relations were cemented shortly afterwards when Gilbert joined Populus, Cooper’s polling company, as a consultant so he could work more overtly for the campaign. In December and January there were also clandestine meetings between Straw, Gilbert, Oliver and Ameet Gill in the basement of the Conrad Hotel, next to St James’s Park tube station.

Despite some hiccups, Stronger In had put together a talented team, and had won the trust of Downing Street. Now they needed the third leg of the Remain stool to step up – the Labour Party.