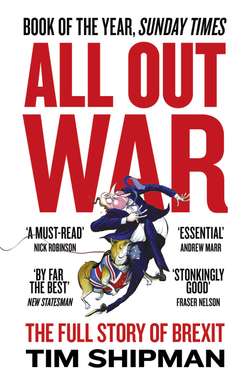

Читать книгу All Out War: The Full Story of How Brexit Sank Britain’s Political Class - Tim Shipman, Tim Shipman - Страница 27

Оглавление9

Boris and Michael

Oliver Letwin was determined to give his mission one more go, even if it was beginning to resemble Mission: Impossible. Cerebral but absent-minded, the Cabinet Office minister was someone who could not be let out in public, but he was David Cameron’s most adept policy fixer.

His task this time was to convince Boris Johnson to back the Remain campaign by producing a new Sovereignty Bill that would enshrine in law the idea that the British Parliament, not the European Court of Justice, was the master of the UK’s destiny. There was just one problem with the plan: every senior government lawyer from the Attorney General downwards believed that each form of words Letwin had come up with was either irrelevant or illegal. Johnson was also coming to that conclusion. The mayor of London had floated the idea himself in early November 2015, and persuaded Cameron to include it in his speech to Chatham House on the day of his ‘Dear Donald’ letter to Tusk. The experience of running up against the limits of what was possible in reforming the EU was pushing Johnson towards the exit door. Michael Gove had not been convinced either, which is why David Cameron had taken responsibility for sorting out the ‘sovereignty lock’ away from the justice secretary and passed it to Letwin.

It was after 9 p.m. on Tuesday, 16 February – two days before Cameron began his summit marathon in Brussels – when Letwin dialled Johnson’s mobile. When the phone went, the mayor of London was sitting at the dinner table in his Islington home, several glasses of wine to the good. Letwin launched into his best case for the sovereignty plan, but had barely opened his mouth when Johnson said, ‘Oliver, how good to hear from you. Do you mind if I put you on speakerphone? I’ve got the lord chancellor here.’ Johnson pushed a plate aside and placed his iPhone between himself and Gove and said, ‘Michael, what would you like to ask?’

Letwin had called to try to circumvent Gove’s growing influence over Johnson, only to find them dining together. His shock can be imagined, but he remained the model of cordiality. He and his officials ran through the latest iteration of the plan as Johnson added Martin Howe, a QC who was the nephew of Thatcher’s foreign secretary Geoffrey Howe, to the call. ‘He was being patched through from Barbados, where he was on holiday,’ says Johnson. ‘Oliver was on the line with his civil servants. We discussed the latest draft. It was obvious listening to Martin Howe that it wasn’t really going to fly.’ Letwin realised he had failed: Johnson would not be persuaded. He reported back to Cameron, who invited Johnson to 10 Downing Street the following day for a final reckoning.

Dinner that night at Johnson’s home in Islington was the most important culinary confab in British politics since Tony Blair and Gordon Brown sealed a pact that would clear the way for Blair to run for the Labour leadership in 1994. The Granita restaurant in which Brown agreed to stand aside, in return for promises still disputed to this day, is long since defunct. But it is noteworthy that its location, 127 Upper Street, was just four hundred yards from Johnson’s home. In its impact on the country, the BoGo Concordat has every right to be considered the more significant event.