Читать книгу Bubblegum and Kipling - Tom Mayer - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

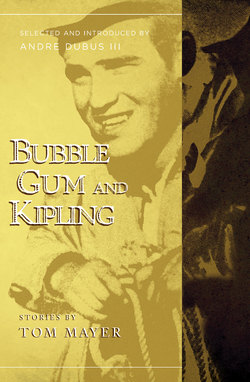

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION BY

ANDRE DUBUS III

I first opened this lovely book in 1971 when I was twelve years old. My parents had divorced only a year or so earlier, and we four kids were living with our newly single mother in a semi-abandoned shipbuilding town on a river just south of the New Hampshire border. Downtown was one empty mill after another, rotted sheets of plywood nailed across their windows and doorways, weeds growing up through cracks in the sidewalk in front of the only businesses that seemed to be still running— a newsstand, a luncheonette, and a dim barroom in front of which were often parked Harley Davidsons, a jukebox inside playing Tom Jones or The Allman Brothers.

My mother had rented a half-house across from a field of weeds where drunks lived all summer long, and on the other side of the house lived another single mother whose TV was never turned off, her young kids running inside and out. It was also a neighborhood of tough and angry kids I tried to keep away from, so for a while I kept close to our new rented half-house, its paint flaking off the clapboards onto the strip of yard between it and the hot sidewalk.

On Sundays our father would pick us up and drive us four kids to church. He was thirty-five years old then and always kept his brown beard neatly trimmed. A few years earlier he had published his first book, a novel called The Lieutenant, and I knew he was a teacher in a college town a few miles up the river, though I rarely thought about him in this way; he was my father, and I missed him, and I was sure somewhere deep inside me that I and my brother and sisters had done something terrible that had made him leave.

One of these Sundays he drove us to a church in Boston forty miles south. He heard its priests preached against the Vietnam War, so we went there, and after Mass, the five of us went walking through Harvard Square. I had never been there before, and I liked how crowded it was with people carrying books or backpacks full of books or guitars slung over their shoulders. Most of the men had long hair and beards, and the women wore tight bellbottom jeans, their hair long and shiny, and in the air were the smells of car exhaust and cigarette and pot smoke and coffee from some cafe. So many of the stores and shops had their doors propped open, and there were long tables set up on the sidewalks and on them were rows of jewelry, handmade leather pocketbooks and wallets, hundreds of albums wedged into cardboard boxes. In front of a big newsstand in the center of the square were five or six tables weighed down with hundreds of books, and this is where our father stopped and began to browse, and so we stopped and began to look through them, too.

I hadn’t read a book since I was nine or ten. It was something I used to enjoy, but with the family breaking up and our mother having to move us from one place to another, reading had fallen away, and now my brother and sisters and I spent a lot of time in front of our black-and-white TV, watching silly game shows and half-hour comedies of laughing, happy people. But my father read books and clearly loved them. I could see it in the way he would pick up each one, turning it over to read the back cover, then slowly opening it to see what was inside. To him they seemed to be sacred objects, and this left me feeling far away from my father and adult life, and that is when he picked up a hardcover book with an orange and charcoal dust jacket and said, “Oh no, man. Not Bubble Gum and Kipling.”

“What’s the matter?”

He explained to me that this was a very good book he’d read when it came out just a few years earlier, but that now it was on the remainder table.

“What’s that mean?”

“It means the publisher has stopped printing them.” My father carried that book into the newsstand, and he bought it and if he gave it to me then I don’t remember that, but I do remember that days later it was raining hard out on the street and the weed field on the other side, and I lay on my bed in the room I shared with my younger brother, and I opened Bubble Gum and Kipling to its title story and began to read.

The first time was in the eighth grade, before Jerry Gordon turned fourteen. It was with a girl named Rita Gomez, and she was thrown out of school later in the year because she was caught doing it with someone else in the weeds behind the backstop.

I did not know this then, but I, too, would do it just before turning fourteen. And it would be with a girl who would also move on from me as quickly as Rita Gomez had moved on from Jerry Gordon, the protagonist of this story and all the other stories in this spare yet beautifully evocative book. What I did know is that somehow this writer, Tom Mayer, had written sentences that forced me to forget they were sentences; instead, in just a few paragraphs, he made me become this boy, Jerry Gordon, sitting in the back row of Mrs. Kline’s English class trying not to get caught with the comic book that big-breasted, bubble–gum-chewing Rita Gomez has just passed to him.

I read through the afternoon and into the early evening, and while I am quite certain that the wonderful stories in Bubble Gum and Kipling were not written for a readership of twelve-year-old boys, it was one of the first books I ever read that showed me what literary art could do: reach out its hand and pull me in and show me that I was not alone.

Forty years later, I find I’ve become a writer of books myself. I have also read hundreds and hundreds of them since that rainy summer afternoon in 1971 and, like my late father, the short story master Andre Dubus, I’ve seen far too many fall out of print and end up on some remainder table out on the street. Maybe some deserve this fate, yet Bubble Gum and Kipling clearly does not; these fine stories, most of them set in the American southwest, still have that same quality I could not have articulated when I first read them; they nearly crackle with an understated and contained dramatic tension, the kind Ernest Hemingway first pioneered, for so much of what happens in these stories—including most of Jerry’s larger thoughts and deeper emotions—lie beneath the surface.

Instead of stating an emotion directly, Tom Mayer—who was only 21 at the time—takes a more artful route. Using either the first person or a close third, he relies upon the physical action itself to render the moment at hand, whether it’s Jerry Gordon training his younger brother for a boxing match, or Jerry making love for the first time, or roping calves, or hearing of the death of his grandmother while he’s away at boarding school, or meeting the train that carries his father’s body and coffin, we experience the thing itself, something Mayer achieves with lean, declarative sentences and a keen eye on the landscape, as in this opening to one of this book’s finest stories, “Homecoming”:

We came up the long rise to the top of the Galisteo shelf at about sixty, which was all the car would do, and then we could see the whole northern end of the Estancia Valley. The steel of the railroad tracks below glinted in the afternoon sun, and we could see the steeple of the church at Lamy behind the rolls in the plain. I could tell there wasn’t much wind, which was unusual, because there weren’t any twisters. Sometimes you can see seven or eight twisters from the top of the shelf.

Mayer goes on here to describe Jerry’s mother sitting in the front seat beside him, “her eyes inflamed and pinkish from a week of crying.” And here, as in all of these compelling and accomplished stories, we begin in the middle, in this case with the Gordon family driving to the train station to retrieve Jerry’s father’s body; Mayer trusts us to catch up and to bring our own losses to Jerry Gordon’s, a boy and young man who, in just eight short stories, comes of age the way young men and women do, slowly and then all at once.

And so it is a cause for true celebration that Pharos Editions has resurrected this subtle and moving collection, allowing new readers to lie back in a room somewhere, maybe with a summer rain falling out in the streets, and step into Tom Mayer’s remarkable, and lasting, Bubble Gum and Kipling.

— ANDRE DUBUS III