Читать книгу Bubblegum and Kipling - Tom Mayer - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

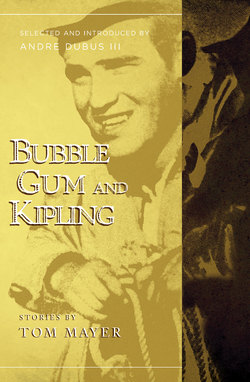

ОглавлениеFOREWORD BY

TOM MAYER

When Pharos Editions asked me if I was interested in reissuing Bubble Gum and Kipling, my first reaction was amazement. I had not read or thought about any of the stories for twenty-five or thirty years. I did not think anyone else had either. I could not remember the titles of several of them. My second reaction was, Probably better to leave sleeping dogs lie.

Finally, I did reread the stories. It was a strange experience. I had no sense of authorship. Much of the material was still fascinating to me, but time, long and frank conversations with my mother as she was dying, and the gyrations of my own life had so changed my perspectives that the stories seemed as if they had been written by someone else.

I liked some of them, but they all were from a world that had turned several times since they were written. I had no desire to revise—changing them would be like messing with an ancient, ancestral sand painting. I doubted if many other people would read them, or like them if they did, but why not find out? I did cut one story from the original book. I thought it was awful, and remembered that the young man who had been me had not liked it himself, and had regretted publishing it all those years ago.

The excision left a very skinny volume. It would have scored on the moron edge of the bell curve of what John O’Hara used to call The Heft Test. To avert accusations of anorexia, Pharos allowed me to include two other, later stories.

I remembered them fine and fondly. “A Cold Wind” seemed like a pretty good glimpse of how as a kid I had reacted to death manifest, and it was my private laboratory for musing on Hemingway’s notion about fiction being like an iceberg. My grandfather did not smoke Bull Durham or carry me about on horseback when I was a child. He was a Chicago lawyer, who traveled by chauffeured Packard. He carried a watch in his vest pocket. It made various noises that were supposed to entrance his grandchildren. Several years before I was born, my father did discover the genuine Alexander in approximately the circumstances I used in the story, but, while bringing the frozen corpse to headquarters, Dad saw a coyote, and, as was his custom, took off cross country in hot pursuit. The coyote escaped. Dad proceeded to the headquarters house, where he told Mother Mr. Alexander had died, that he had the remains in the truck, did she wish to accompany him while he took them to the funeral home. (The one he had in mind was owned by a man whose synthetic dignity made you think he might be a W. C. Fields impersonator. Dad considered any meeting with him free entertainment, greeted him by asking, “How’s business? I hear you’re getting a lotta new customers.”)

Mother, glancing in the bed before climbing in the pick up: “Where’s Mr. Alexander?”

Dad: “In back. I told you.”

Mother: “You might want to look again. Are you sure he was dead? I don’t believe in resurrection.”

Dad: “He must have bounced out while I was after the coyote.”

After an extensive search, Dad rediscovered the corpse, camouflaged by partial burial in a snowdrift, and reloaded it.

Mother: “How could you? You completely forget that poor gentle old man, while you go charging off and have a wonderful time chasing a coyote. Only you.”

Dad: “Jesus Christ, Peach. There was no place he had to be, and he didn’t feel a goddamned thing.”

A rancher my parents liked did buy his dentures by mail order, and did shape them himself. To give you an idea how far Hemingway’s theory may reach, in case there’s any validity to it, the man’s son was Llewellyn Thompson, one of the great American diplomats, the guy the histories say prevented World War III by telling Kennedy what to say to Khrushchev.

I still haven’t decided if the Cuban Missile Crisis, trick pocket watches, or what Dad and Mother said to each other after Dad lost the corpse while trying to get a shot at a coyote are subsurface structural essentials, but the proposition is one I enjoy contemplating for a half hour once every couple of years.

“The Top of the World” seemed to me a fair sketch of a certain kind of rich Mexican. I worked for a man much like him for awhile. I stole everything about him, his friends, and their family histories that fitted the story. The pilot had a few traits I was familiar with as well: No good at marriage; a teacher who did not like teaching; a fellow who was not a cheerful, natural organization man. I once got involved at the fringes of a presidential campaign. My candidate lost a two-horse race at the national nominating convention by a vote of 1347 to 1, a ratio I thought might serve as a mathematical representation of the pilot in this story. Of all these stories, “The Top of the World” may contain the lowest proportion of autobiographical detail but, perhaps, it is the most personal.

— TOM MAYER