Читать книгу Branson - Tom Bower - Страница 12

5 Dream thief

ОглавлениеRichard Branson prided himself on judging within one minute whether he liked or disliked a stranger. Fat Americans were unlikely to pass his aesthetic test but Branson’s cultivated ambiguity and awkward hesitations disguised his prejudices, especially if an interesting offer was on the table.

The thirty-one-year-old American Jew was proposing joint ownership of an all-business-class airline flying between Britain and the United States. In the wake of Laker Airways’ collapse in 1982 and the popularity of People Express, a discount airline, Fields was following the instincts of many regular air travellers entranced by the glamour of public applause and profits.

Gut instinct rather than careful research persuaded Branson in ‘thirty seconds’ after reading Fields’s business plan that he was ‘excited’. Despite having risked and lost money in pubs, film production and shops, Branson was undaunted by possibly risking £3 million on an airline. The son of a former air hostess calculated that an airline would be ‘fun’. With all the tickets bought in advance, there would be huge cash deposits in his bank account. If the staff received low wages like other Virgin employees, and costs were controlled, there might be profits. He could easily persuade Fields to abandon the notion of an all-business-class airline. Over weekends and holidays, businessmen would not be flying. There was, he loved to enunciate, ‘a thin line’ between an entrepreneur and an adventurer. The buccaneer was back in business.

‘You’re mad,’ scowled Simon Draper who, supported by Ken Berry, was appalled by the idea. Branson grinned. His cousin could not grasp the joy for a restless gambler to shift gear. Majestic resolution shone from his face. ‘You’re a megalomaniac, Richard,’ continued Draper. ‘What I’m telling you is that you go ahead with this over my dead body.’ Branson had never welcomed criticism. He was accountable to no one, even to the architect of his musical fortunes. His relationship with Draper was suddenly and permanently fractured. After fifteen years of fluctuating business experience with only one major success, Branson was certain that he could overturn the old adage that the best way to become a millionaire was to be a billionaire and start an airline.

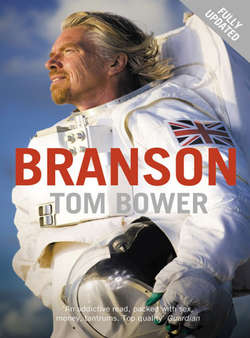

A mere four months later, on 29 February 1984, Branson and Fields posed in public to launch their airline. Dressed in First World War flying gear – a leather helmet and goggles – to encourage the newspaper editors to publish a picture, Branson, the new people’s champion, listed the benefits Virgin would provide for thousands of Britons to fly cheaply to New York. No journalist, Branson knew, would question his sincerity. Glossing over weak finances was concomitant with exaggerations about the cheapest fares and minimising Virgin Atlantic’s provision of the same cramped seats and unreliable service as People Express.

The photographs showed Fields, the airline’s joint owner, smiling. Disguised was Fields’s frustration that Branson had still not signed a contract or released his promised £3 million to finance the airline. Branson’s concealment of the disagreement in front of the journalists gave him as much pleasure as dressing up. Disguises of all kinds appealed to him.

In the helter-skelter activity to create an airline within four months, Branson had nonchalantly forgotten what he owed to Fields. It was not only the idea of the airline: before their introduction, the American had started negotiations with Boeing to lease a second-hand 747 on condition that it could be returned at no cost after one year; Fields had identified the prematurely retired British Airways and British Caledonian flying crews prepared to work at low salaries; and Fields had recruited the former Laker executives who would hire and train the cabin, ticketing and service staff. Inevitably, the new airline was a clone, an inheritance from all the existing carriers.

Taking over the negotiations, Branson assumed the credit for Fields’s achievements and added two new ideas. ‘I know what I don’t like about flying,’ he said. ‘The boredom and not enough leg room.’ The new airline should offer something different. Business class passengers would be given extra space and also individual hand-held video screens with the choice of dozens of films.

‘Let’s announce a £30 million advertising campaign,’ he suggested.

‘But we haven’t got £30 million,’ stuttered the new marketing manager.

‘Course not,’ replied Branson, ‘but we’ll announce it, get the newspaper coverage and won’t do anything more.’

‘Richard’s embellishments’ were introduced to men previously accustomed to routine corporate life. One observed: ‘It seems that he likes multiplying everything by ten.’

Amid the furore and hype, only Randolph Fields stood isolated from the euphoria. The American suspected that Branson was a dream thief. Even after their press conference announcing the creation of the airline, Branson delayed signing an agreement binding the two men as partners.

Branson’s delay was deliberate. The partnership with Fields was of little interest unless concluded on Branson’s terms. Contrary to their original agreement of equality, Branson wanted a majority share and control of the airline. Since Virgin Atlantic could only be launched with his £3 million, Branson began squeezing Fields to surrender. Branson’s favoured method was to procrastinate until the plum fell for as little money as possible. If Fields lacked the cool courage and bargaining strength to outface his demands, that was the American’s misfortune. If Fields departed, Branson would feel no loss.

Branson was, however, vulnerable. Unprofitable film investments had suddenly plunged Virgin into another cash crisis. The company’s overdraft was bumping close to £3 million. He had concealed the crisis from Fields by flaunting the profits Virgin had earned from the success of Boy George’s song, ‘Do You Really Want to Hurt Me?’, and more importantly from the Civil Aviation Authority. ‘I decided not to mention [to the CAA],’ he would confess about Virgin’s application for the original licence, ‘that we were having to pay out large sums of money to continue making 1984’, a disastrous feature film. Unfortunately for Branson, Fields held a trump card. Without an agreement and Virgin’s deposit of £3 million, the CAA would not issue a licence for the airline to fly. Branson lacked any flexibility to manoeuvre. He signed the contract, deposited the money and invited Fields to the houseboat to celebrate with a glass of cheap, warm white wine.

In Branson’s world, signed contracts were only valid if they could be enforced. Whenever necessary and legally possible, he would doggedly renegotiate the contractual terms to tilt the balance in his favour. On the eve of the airline’s launch, he knew that Fields was powerless to enforce the contract they had just signed. Many of the airline’s staff had refused to work with the excitable lawyer and by then Virgin Atlantic Airways was wholly associated with Branson. His threat to Fields was pure theatre: ‘My bankers won’t let me do it. Unless we control the company, we’ll have to walk away from this deal.’ Blaming bankers, like blaming lawyers, was a familiar ploy. ‘I’m having none of this,’ fumed Fields and he stormed off the boat.

Branson contacted the CAA. If he quickly reapplied for a new licence without Fields, he inquired, could it be approved? The reply was discouraging. A new application, he was told, would require months to be processed. His stratagem failed. Within the hour, Branson had telephoned Fields and withdrawn his threat.

The next morning Branson started again. His aggression was as persistent as his pursuit of publicity. The agreed terms, Branson told Fields, made him ‘feel very uncomfortable’. He wanted revisions.

Branson’s style was difficult to deflect. The even-tempered upper-class voice was full of imploring reasonableness. The pullover and houseboat shrieked modesty. Gradually, even the irascible Fields was disarmed. After four days of haggling, Fields’s wariness had become weariness. Finally, he surrendered to attrition. Exhausted, he persuaded himself that Branson was the sort of man he could trust. Under the new deal, Branson would own 75 per cent and Fields 25 per cent of their company. Fields consoled himself that his interests remained firmly protected in the small print. Branson also congratulated himself on winning control thanks to the contract’s same small print. ‘He’s on his way,’ he gurgled about his partner.

On 22 June 1984, 34,000 feet above the Atlantic Richard Branson had every reason to congratulate himself. To the sound of Madonna’s hit, ‘Like a Virgin’, he was wearing a steward’s hat and pouring eight hundred bottles of champagne into the glasses of four hundred guests celebrating the launch of Virgin Atlantic Airlines. The party was more than memorable, it was unique. The sight of the famous dancing in the aisles and the pouting, red-suited Virgin hostesses offering food prepared by Maxims was a triumph of Branson’s presentational skills. His tenacity had transformed a rejected proposal by a young American lawyer into a major media event. When his boisterous guests returned to London after another party at Newark Airport, the capital buzzed that flying Branson was fun. No one could recall the austere Scottish gals of British Caledonian or the prim matrons of British Airways running out of champagne during a riotous party over the Atlantic. Virgin, a name until then only known to record buyers, had become a recognisable brand basking in goodwill.

In August that year the houseboat was the obvious venue to receive the representative of the Wall Street Journal who sought an interview. Stripped to the waist, wearing baggy trousers, no shoes and with a hole in his socks, the informal tycoon welcomed his guest to spread the new gospel: ‘We’re becoming a global entertainment company and we’re going into the United States big.’ Virgin Records successes, he rattled off, included Genesis, Phil Collins, Human League, UB40 and Mike Oldfield. The Sex Pistols had sold one million albums and Boy George had just scored a major hit in America. Virgin Films had been promised $45 million from investors following the ‘success’ of Electric Dreams due to be released in one thousand four hundred American cinemas, and 1984 was next. Virgin was also launching a music cable channel, a book publishing company, a video game division and a record label in America. ‘That’s how we maximize profit,’ he repeated, mouthing ‘synergy’, the latest cliché of the Bonfire of the Vanities era.

At the end of his monologue Branson was satisfied that his guest was suitably awed. No discomforting question required him to reconcile his new global ambitions with his other script, ‘We want to stay small because small is profitable.’ The contradictions had passed unnoticed and no doubts were raised about Virgin’s finances. Branson’s performance had chameleon-like qualities, adjusting itself to please its audience and to distract from any contradictions within.

‘I’m not on a crusade with this thing,’ Branson had modestly told his American interviewer about his new airline. ‘If we had to pack it all in, the whole venture wouldn’t cost but two months’ profit of the Virgin Group.’ ‘Packing it in’ was far from Branson’s mind. The excitement of owning an airline bit deep. His only concern was managing the chaos of operating even one aeroplane. Maiden Voyager, Virgin’s single Boeing 747, was occasionally flying either empty across the Atlantic or airport staff were cowering in fear of lynching from crowds of irate passengers complaining about gross overbooking. Administration and technical troubles were causing delays. Occasionally, flights were cancelled when the plane’s load was genuinely too low to earn profits and passengers were placated by talk of ‘technical problems’. To make a virtue of those problems, Branson regularly telephoned or travelled to Gatwick to apologise to passengers about his ‘teething troubles’.

His early flights on Virgin Atlantic’s single 747 to New York convinced him that only ruthless care over his finances would guarantee the airline’s prosperity. The 747’s bubble for business class was often empty during the summer. In winter, he knew, when the major airlines reduced their fares, it would be even harder to fill his jumbo. Copying the blueprint of Laker and People Express had been wrong. ‘I knew we had to start working very hard to make sure that within a few years half the plane would be full of business class passengers,’ he said. The model to emulate, he realised, was British Caledonian. Their extras had established a uniqueness. Copying British Caledonian, Virgin would also offer business class flyers better seats, two-for-one fares, a special lounge at the airport and a free limousine service. Presenting the old as the new was Branson’s genius but one frustration was unassuaged. After the first burst of publicity, Virgin Atlantic had become unmentioned in the media. The indifference was intolerable. ‘We need to make waves,’ he told his marketing executives.

Stunts and gimmicks were Branson’s only tool to find thousands of new customers, especially in America. When a couple were bounced from an overbooked Virgin flight to New York and complained that they would miss seeing their deceased son in his coffin before the funeral, an anonymous marketing executive had, on his own initiative, bought tickets for their flight on Concorde. Within minutes of their flight leaving Heathrow, Virgin’s publicity machine fed to the media how Branson’s personal intervention had rescued the heartbroken parents. The cause of their ‘heartbreak’, Virgin’s chaos, was brushed aside. Branson understood how to turn every negative into a positive story.

‘BA has just fired a girl and she’s protesting,’ laughed an aide.

‘Hire her,’ ordered Branson.

‘What?’

‘Hire her straight away and get the publicists to tell all the media how Virgin saved the poor girl.’

But the small news items could not compete with the big budget campaigns orchestrated by British Airways and the American airlines. ‘They’re so greedy,’ Branson repeatedly moaned, frustrated by BA’s invincibility. ‘They’re so big.’ Influenced by Freddie Laker, he feared BA’s misuse of their huge advantages and goodwill against a newcomer. As a customer, too, Branson had every reason to dislike BA. Despite the appointment of Lord King in 1981 to revolutionise the state-owned airline for future privatisation, the corporate culture still reeked of imperious military officers managing an engineering corporation. BA’s administrators resembled Whitehall civil servants rather than entrepreneurs and most of the cabin staff patronised the ‘punters’, as they unlovingly called their passengers.

Branson had good reason to welcome those deficiencies. British Airways’ weaknesses were his opportunity to earn profits, although Virgin’s single Boeing 747 operating on a peripheral route (Gatwick to Newark) against BA’s two hundred and fifty aircraft did not even register on the giant’s horizon. Branson, however, wanted to be noticed, especially to attract passengers. His tactic was to play the ‘victim’ card. His weapons were pranks. ‘We’re the cheeky airline having fun at the expense of a dinosaur,’ he proclaimed.

In establishing Virgin Atlantic, Branson had frequently consulted Freddie Laker, the founder of Skytrain which had collapsed in 1982. At their meetings, Laker had inculcated Branson with his complaint that British Airways and the other major transatlantic airlines had conspired to destroy his airline by undercutting Skytrain’s fares. That depiction appealed to Branson. He preferred not to inquire about another cause of Laker’s collapse: that the flamboyant businessman had imprudently purchased three DC-10 aircraft financed by an unprotected £350 million loan just as fares were tumbling and before he received permission to fly the planes between London and New York. Laker also preferred to ignore his own imprudence, describing Skytrain as the ‘victim’ of BA’s cartel.

If any British airline had cause to scream ‘victim’, it was British Caledonian, then British Airways’ national competitor, which operated twenty-seven planes. But the managers of British Caledonian usually desisted. Flying was a cut-throat business and every entrant knew that survival depended upon attrition.

Ruthless competition was as natural to Branson as commercial warfare. In seventeen years, he had lied about his finances, he had lured managers, dealt harshly in litigation, denounced friends and had perpetrated a fraud against Customs and Excise. There was an instinctive progression from manipulating individuals in business deals to manipulating public opinion in his favour. Competition, to Branson, implied attacking British Airways. Freddie Laker had attempted the same but Branson subtly concealed his motives – his lust for money and power – by emphasising his altruism. Within days, the people’s champion was conceived and born. His first attack coincided with the traditional autumn slump in ticket sales.

In October 1984, British Airways and the American airlines announced their usual price cuts. BA’s was a reduction of £19 to New York, from £278 to £259, just £1 above Virgin’s fare. Virgin had not featured in BA’s calculations. The four-month-old airline operating between Gatwick and Newark, was invisible. Branson’s remedy, in a deliberate echo of Laker’s campaign, was to bombard the government with complaints that BA’s new price was ‘predatory’ and calculated to destroy Virgin.

The complaint was ignored and Virgin’s fares were cut, but in later years sympathetic journalists would accept Branson’s version: the cut in the 1984 price constituted British Airways’ first attempt to destroy Virgin Atlantic. His assertion was nonsense. The real victim in autumn 1984 was Randolph Fields, a casualty of Branson’s ambition to be crowned an airline tycoon.

Partners irritated Branson, especially those who criticised his decisions. Field’s latest challenge, Branson decided, was intolerable. ‘Your staff at Virgin are making contracts on behalf of Virgin Atlantic without consulting me,’ complained Fields. ‘I’m a director.’ Additionally, complained Fields, Virgin Atlantic’s avalanche of cash from advance ticket sales was being used by Virgin Records as if there were a common pot. Branson scoffed denial and outrage. Shuffling money around was normal. Intolerant of criticism, he would not be accountable to anyone. Fields had miscalculated: he was about to discover that he had married a vulture. Branson’s tactics were merciless. Formally, Virgin Atlantic announced the appointment of a new director to outvote Fields at board meetings. To stop Branson, Fields appealed to the court for an injunction. He won and departed with the judge’s condemnation of Branson’s behaviour as having ‘left a bad taste in my mouth’. But the American’s legal victory was pyrrhic. Branson ordered that the locks on Fields’s office should be changed. Pleading, begging and screaming with Branson for reason, Fields was reduced to tears by a man whom he damned to his friends as ‘The Devil’. Finally, he accepted defeat and surrendered.

In the settlement on 1 May 1985, Branson paid £1 million for the American’s shares and promised a lifetime of free flights across the Atlantic on Virgin planes for Fields and his family. Branson was content. Knowing that Fields had lost was satisfying. But for Branson, minded to count every penny, the free flights rapidly became irksome. Fields’s frequent use of the concession, he estimated, cost $500,000 in the first year. Branson disputed the agreement and was again summoned by Fields to court. Branson had no chance of winning. The contract unambiguously gave Fields the right to unlimited flights. Branson was nevertheless determined to make Fields fight for his rights, gambling that a judge might be persuaded against Fields. He was unlucky. The judgment was clear and merciless. Fields’s victory found little sympathy in London. The general goodwill towards Branson neutralised Fields just as it silenced Branson’s other victims.

His performance was perfect. While Fields complained to friends about Branson’s ruthless negotiations, that image was unknown to most of Branson’s employees and the public. To the vast majority, he was a charming, fun-loving and blessed entrepreneur, readily embraced by the people.