Читать книгу Branson - Tom Bower - Страница 5

Preface

ОглавлениеOn 16 December 1998, Sir Richard Branson was preparing to set off from Marrakesh in an attempt to become the first person to circumnavigate the world in a hot-air balloon. Over the previous days I had sought to join his party in Morocco to witness a Branson extravaganza. I was still undecided whether to write a book about Branson but expected that the experience might influence my decision. That morning, my place on Virgin’s chartered jet on behalf of a national newspaper was suddenly cancelled.

To my surprise, at lunchtime the same day, I received a brutal, defamatory and untrue letter from Branson, whom I had never met, faxed by his London office. Branson alleged that he had received ‘a number of calls over the last six weeks from various friends and relatives who have been upset by your researchers/detectives’. He claimed that on my behalf these hired hands had ‘doorstepped’ a woman and uttered ‘untrue accusations that her son is, in fact, my son’. Not surprisingly, he continued, that behaviour had ‘caused a lot of upset to all the people concerned including the real father’. Since those same people were flying to Marrakesh for the launch of the balloon, he felt it would be ‘inappropriate’ for me to be present. ‘To be perfectly honest,’ he added, ‘none of them would particularly welcome it.’ Branson concluded that after the trip was completed we could discuss ‘what exactly it is you are after’.

I was flabbergasted by Branson’s letter. I had never heard of the people he mentioned. I had not employed any detectives nor had I asked or heard of anyone doorstepping these people. In a faxed reply, I immediately protested.

Three days later, I received a response. In an unexpected call to my mobile phone, an unfamiliar voice announced, ‘Tom, I’m sorry about that.’

‘Who is that?’ I asked, puzzled.

‘It’s Richard,’ he replied.

‘Richard who?’

‘Richard Branson.’

‘But I thought you were in a balloon.’

‘I am.’

‘Where are you?’

‘Dunno,’ he replied and could be heard asking about his location. ‘Over Algeria,’ he continued and then said, ‘Look, I’m sorry. When I get back, let’s meet and talk things through.’

His bizarre behaviour persuaded me that the real Branson, his methods and his operation remained, despite all the publicity, unknown.

About ten weeks earlier, a tiny announcement in an obscure part of the Financial Times about a management resignation from Victory, Branson’s new clothing corporation, had alerted my curiosity. The senior director, the newspaper’s four-line report recorded, was departing after just five months because ‘there was no role for an executive chairman’.

Branson’s new company, I knew, was spiralling into debt. The management change could only have been caused by anxiety. Virgin’s official denials of problems fuelled my suspicions.

Hence, in January 1999, I began this book. Despite his suggestion that we should meet, I never heard from Branson personally, though I soon became aware of his attitude. Several people I approached for interviews told me that, ‘after checking’, they would prefer not to meet. I had the distinct impression that Branson or the Virgin press office was discouraging people. From other comments, it appeared that Branson was unwilling to either help or meet me.

On 22 October 1999, having made substantial progress, I nevertheless wrote to Branson asking ‘whether you would reconsider your position and agree to meet?’ On 6 December, explaining that my letter had only just arrived, he replied: ‘I have been called by a large number of people who you have interviewed about me. Most told the same story, namely that you have a fixed agenda and that no amount of persuasion or argument by them to the contrary appeared to have any influence on you. As it would therefore appear that you have pre-judged me, it would seem that little benefit or pleasure would come from our meeting.’

That was, I believed, impolite and inaccurate. By then, I had interviewed over two hundred people. Many were his sympathisers. I had deliberately sought their opinions to produce an objective book. Certainly, I posed as a devil’s advocate in testing his admirers’ opinions. The technique is reliable and is even favoured by Sir Richard himself. But there was no justification for concluding that my questions confirmed prejudice. On the contrary, I had striven to understand a man who declined my attempts to meet to hear his opinions.

In his letter of 6 December 1999, Branson did offer to answer any written questions and also requested to read the manuscript of the book. He would later express himself to be ‘very disappointed’ that I had not allowed him to vet and approve this book prior to publication.

On 11 January 2000, I submitted nine questions. On 18 February, he sent his replies. They contained one serious error, namely about the circumstances and timing of a Japanese investment in Virgin Music in 1989. The significance of Branson’s error will become apparent to the reader at the beginning of this book.

By February 2000, however, the relationship between Branson and myself had become complicated. Branson was upset by an article I had written in December 1999 in the Evening Standard about his bid for the National Lottery. He believed my comments to be defamatory.

As we exchanged letters about the article and I replied to his threat of commencing legal proceedings if I failed to publish an apology, I was reminded about his letter to the Spectator on 28 February 1998 protesting about another journalist, where he recorded, ‘I have never sued anyone to suppress criticism of myself or Virgin.’ Two years later, on 22 March 2000, that boast became redundant.

In an operation seemingly co-ordinated with The Times, a leather-clad motorcyclist served a writ issued by Branson while I was answering questions from a journalist who happened to telephone at the precise moment the writ was served. Branson’s action was considered of such importance that The Times prominently reported the writ on its front page the following day.

Of the many unusual aspects of Branson’s resort to legal action, few were more significant than his decision to sue me exclusively and not, as is customary, also the newspaper which published the article. Branson’s decision to deliberately exclude the newspaper was interpreted by my legal advisers as an attempt to undermine the publication of this book. The plan was obvious.

Confronted by the impossibility of matching Branson’s self-proclaimed fortune to finance a team of lawyers, I would have been forced to capitulate and apologise, and inevitably discredit my own book. Fortunately, Max Hastings, the Evening Standard’s editor, pledged in a prominent article to finance the defence of the piece which his newspaper had published.

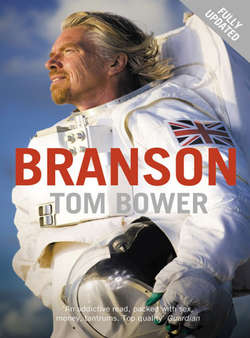

At the time I wrote this book, there had been two biographies and one autobiography about Richard Branson. All three benefited from Sir Richard’s vetting and approval. I resisted that blessing. This book is offered as a balanced review of Britain’s most visible entrepreneur, an eager recipient of hero worship, trying to influence practically every aspect of British society, who, in his attempt to market a Virgin lifestyle, seeks the widest possible circle of influence.