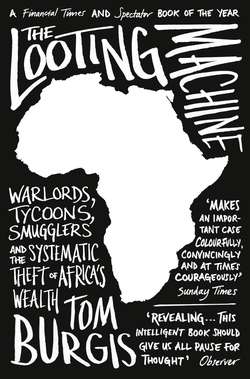

Читать книгу The Looting Machine: Warlords, Tycoons, Smugglers and the Systematic Theft of Africa’s Wealth - Tom Burgis, Tom Burgis - Страница 11

2 ‘It Is Forbidden to Piss in the Park’

ОглавлениеIT IS HARD to imagine a place more beautiful than the east of the Democratic Republic of Congo. The valleys are a higher order of green, dense with the generous, curving leaves of banana plants and the smaller, jagged ones of cassava shrubs. The hillsides are a vertiginous patchwork of plots. Just before dusk each day the valleys fill with a spectral mist, as though Earth itself had exhaled. The slopes drop down to Lake Kivu, one of the smaller of central Africa’s great lakes but still large enough to cover Luxembourg. On some days the waters lap serenely; on others, when the wind gets up, the lake turns slate-grey and froths. At the northern shore stand the Virunga, Lake Kivu’s crown of volcanoes.

Beneath the beauty there is danger. From time to time the volcanoes tip lava onto the towns below. Cholera bacteria lie in wait in Lake Kivu’s shallows. Deeper and more menacing still are the methane and carbon dioxide dissolved in the water, enough to send an asphyxiating cloud over the heavily populated settlements on the shores should a tectonic spasm upset the lake’s chemical balance.

But there is something else that lies under eastern Congo: minerals as rich as the hillsides are lush. Here there are ores bearing gold, tin and tungsten – and another known as columbite-tantalite, or coltan for short. Coltan contains a metal whose name tantalum is derived from that of the Greek mythological figure Tantalus. Although the Greek gods favoured him, he was ‘not able to digest his great prosperity, and for his greed he gained overpowering ruin’.1 His eternal punishment was to stand up to his chin in water that, when he tried to drink, receded, and beneath trees whose branches would be blown out of reach when he tried to pluck their fruit. His story is a parable not just for the East but for the whole of a country the size of western Europe that groans with natural riches but whose people are tormented by penury. The Congolese are consistently rated as the planet’s poorest people, significantly worse off than other destitute Africans. In the decade from 2000, the Congolese were the only nationality whose gross domestic product per capita, a rough measure of average incomes, was less than a dollar a day.2

Tantalum’s extremely high melting point and conductivity mean that electronic components made from it can be much smaller than those made from other metals. It is because tantalum capacitors can be small that the designers of electronic gadgets have been able to make them ever more compact and, over the past couple of decades, ubiquitous.

Congo is not the only repository of tantalum-bearing ores. Campaigners and reporters perennially declare that eastern Congo holds 80 per cent of known stocks, but the figure is without foundation. Based on what sketchy data there are, Michael Nest, the author of a study of coltan, calculates that Congo and surrounding countries have about 10 per cent of known reserves of tantalum-bearing ores.3 The real figures might be much higher, given that reserves elsewhere have been much more comprehensively assessed. Nonetheless, Congo still ranks as the second-most important producer of tantalum ores, after Australia, accounting for what Nest estimates to be 20 per cent of annual supplies. Depending on the vagaries of supply chains, if you have a PlayStation or a pacemaker, an iPod, a laptop or a mobile phone, there is roughly a one-in-five chance that a tiny piece of eastern Congo is pulsing within it.

The insatiable demand for consumer electronics has exacted a terrible price. The coltan trade has helped fund local militias and foreign armies that have terrorized eastern Congo for two decades, turning what should be a paradise into a crucible of war.

Edouard Mwangachuchu Hizi avoided the brutal end that befell many of his fellow Congolese Tutsi as the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide of 1994 spilled across the border, but he suffered nonetheless. The son of a well-to-do cattle farmer, Mwangachuchu was in his early forties and working as a financial adviser to the local government in Goma, the lakeside capital of eastern Congo’s North Kivu province, when extremist Hutus on the other side of the water in Rwanda embarked on what is reckoned to be the fastest mass extermination in history, butchering eight hundred thousand Tutsi and moderate Hutus in one hundred days. Two million people fled, many of them into eastern Congo, where analogous ethnic tensions were already simmering.

On his way to work one day in 1995 a mob dragged Mwangachuchu from his jeep.4 He was choked with his tie and stripped. The mob dumped him at the border with Rwanda, where Tutsi rebels had seized control from the Hutu-led government following the genocide. His herds slaughtered, Mwangachuchu found himself among the flotsam of war, albeit more fortunate than those consigned to the squalid refugee camps beside Lake Kivu. He was granted asylum in the United States in 1996, along with his wife and six children.

Mwangachuchu watched from afar as the Hutu génocidaires licked their wounds in eastern Congo and began to launch raids against the new Tutsi-led authorities in Rwanda. He looked on from Maryland as Paul Kagame, the steely guerrilla who had become Rwanda’s leader, and his regional allies plucked an obscure Congolese Marxist rebel called Laurent-Désiré Kabila from exile in Tanzania to head a rebel alliance that swept through eastern Congo. The rebels perpetrated revenge massacres against Rwandan Hutu refugees and génocidaires as they went and then pushed on westward across a country the size of western Europe, all the way to Kinshasa, Congo’s capital. They toppled Mobutu Sese Seko, the decrepit kleptocrat, and installed Kabila as president in 1997. But Kabila barely had time to change the country’s name from Zaïre to the Democratic Republic of Congo before his alliance with his most powerful backer, Rwanda, started to fray. A little over a year after he took power, after Kabila had begun to enlist Hutu génocidaires to counter what he perceived as a Tutsi threat to his incipient rule, the alliance snapped. Half a dozen African armies and a score of rebel groups plunged Congo into five more years of war, during which millions died.

When Mwangachuchu went home in 1998, the dynamics of eastern Congo were shifting once again. Anti-Kabila rebels supported by Rwanda’s Tutsi-led government had taken control of the East. No one in this ethnic cauldron is ever safe, but the latest realignment favoured Congolese Tutsis like Mwangachuchu. He set about reclaiming his ancestral lands at Bibatama, 50 kilometres northwest of Goma. Mwangachuchu knew that the territory contained something still more precious than fertile pastures for grazing cattle – the rocks beneath were rich with coltan.5

Investors from Congo’s old colonial master, Belgium, had mined the area around Mwangachuchu’s lands, but their joint venture with the government had collapsed in the mid-1990s. Invading Rwandan forces and their allies looted thousands of tons of coltan and cassiterite, the tin-bearing ore, from the company’s stockpiles, UN investigators found.6 When Mwangachuchu arrived home, artisanal miners around his mountain hometown were hacking away at the rock with picks and shovels. The cassiterite would fetch a few dollars per kilo. But far-off developments in global markets were about to spur the coltan trade – and pour cash into eastern Congo’s war.

The boom in mobile phones as well as in the rest of consumer electronics and games consoles caused voracious demand for tantalum. The two biggest companies that processed tantalum, Cabot of the United States and H. C. Starck of Germany, foresaw prolonged high demand. They signed long-term contracts, locking in their supply of tantalum ores.7 That created a shortage on the open market and sparked a scramble to find new supply sources. In the course of 2000, prices for tantalum ores rose tenfold. Congo was ripe for the picking.

Thousands of eastern Congolese rushed into coltan mining. Many exchanged a farmer’s machete for a miner’s pick. Militias press-ganged others into mining. Livestock had long been the East’s most prized commodity, but now, suddenly, it was coltan. In 1999 North Kivu officially exported five tonnes of coltan; in 2001 it exported ninety tonnes. Even after the flood of Congolese supply brought the world price back down, coltan remained more lucrative than other ores.

Coltan was not the sole catalyst of the conflict – far from it. Congo was seething before the boom and would have seethed even if coltan had never been found. But the surging coltan trade magnified eastern Congo’s minerals’ potential to sustain the myriad factions that were using the hostilities to make money. ‘Thanks to economic networks that had been established in 1998 and 1999 during the first years of the Congo war, minerals traders and military officials were perfectly placed to funnel [coltan] out of the country,’ writes Nest.8

Mwangachuchu started mining his land in 2001, employing about a thousand men. An amiable man with an oval face and soft features, he breaks bread with his workers and sometimes even works the mines himself, people who know him told me. Mwangachuchu Hizi International (MHI), the business he founded with his partner, a doctor from Baltimore named Robert Sussman, swiftly came to account for a large chunk of North Kivu’s coltan output. ‘We are proud of what we are doing in Congo,’ Sussman said at the time. ‘We want the world to understand that if it’s done right, coltan can be good for this country.’9 But UN investigators and western campaigners were starting to draw attention to the role Congo’s mineral trade played in funding the war. The airline that had been transporting MHI’s ore to Europe severed ties with the company. ‘We don’t understand why they are doing this,’ Mwangachuchu told a reporter. ‘The Congolese have a right to make business in their own country.’10

Other foreign businesspeople were less concerned about doing business in a war zone, which is what eastern Congo remained even after the formal end of hostilities in 2003. Estimates I have heard of the proportion of Congolese mineral production that is smuggled out of the country range from 30 to 80 per cent. Perhaps half of the coltan that for years Rwanda exported as its own was actually Congolese.11

Militias and the Congolese army directly control some mining operations and extract taxes and protection money from others. Corrupt officials facilitate the trade. The comptoirs, or trading houses, of Goma on the border with Rwanda orchestrate the flow of both officially declared mineral exports and smuggled cargoes. Other illicit routes run directly from mines across the Rwandan and Ugandan borders. UN investigators have documented European and Asian companies purchasing pillaged Congolese minerals. Once the ores are out of the country, it is a simple step to refine them and then sell the gold, tin, or tantalum to manufacturers. The road may be circuitous, but it leads from the heart of Congo’s war to anywhere mobile phones and laptops can be found.

In the absence of anything resembling a functioning state, an ever-shifting array of armed groups continues to profit from lawlessness, burrowing for minerals and preying on a population that, like Tantalus, is condemned to suffer in the midst of plenty. In 2007 Mwangachuchu fell out with Robert Sussman, the co-founder of his mining business, a dispute that would lead a Maryland court to order the Congolese to pay the American $2 million. Mwangachuchu pressed on alone. His lands went on yielding up their precious ore. And he began to cultivate a new partner: the Congrès National pour la Défense du Peuple (National Congress for the Defence of the People), a militia that largely does the opposite of what its name suggests.

The relentless conflict in eastern Congo has prevented the development of large-scale industrial mining there. Almost all mining is done by hand. The East’s minerals have fuelled the war, but the value of its output is tiny compared with the immense mines to the south.

Congo’s Katanga province, sandwiched between Angola and Zambia, holds about half of the world’s stocks of cobalt.12 The metal is mostly used to make the ultra-strong superalloys that are integral to turbines and jet engines. It is mined as a by-product of copper, a crucial ingredient of human civilization, from its first uses in ancient coins to the wiring in electricity networks. The African copperbelt stretches from northern Zambia into Katanga and holds some of the planet’s richest copper stocks. In Katanga vast whorls of red earth and rock have been cut into the forest, open pit mines that descend in steps like amphitheatres.

Katanga has endured secessionist conflict and suffered heavy fighting during the war. But, lying much further from the border with Rwanda, the principal foreign protagonist in the rolling conflicts, Katanga has known more stability than the East. Mining multinationals from Canada, the United States, Europe, Australia, South Africa and China have operations in Katanga; the region’s mining output dwarfs the rest of Congo’s economy. Congo’s rulers have built a shadow state on the foundations of Katanga’s minerals, resembling the one that Angola’s Futungo has fashioned from crude oil.

Augustin Katumba Mwanke grew up in Katanga idolizing the executives who ran Gécamines, the national copper-mining company. As Congo crumbled in the dying years of Mobutu’s rule, a combination of fierce intelligence, luck and determination carried him to South Africa, then brimming with possibility after the end of apartheid. He worked for mining companies before landing a job at a subsidiary of HSBC. In April 1997, when Laurent Kabila’s forces captured Katanga on their advance across Congo, the bank grew nervous that the rebels might not honour a loan it had made to Gécamines. A delegation was dispatched to Congo for talks with the rebels. Katumba was added to the party in the hope that a Congolese face might help the bank’s cause.13

‘When they came I saw a young man who looked very bright,’ Mawapanga Mwana Nanga, then the rebels’ finance chief, told me years later.14 An agronomist who had trained in Kentucky, Mawapanga was on the lookout for talented recruits as he prepared to inherit a ransacked treasury. He took a shine to Katumba. ‘I told him, “You should come back. The country needs people like you.” We were just joking. I said, “I can give you a job, but I can’t pay you yet.”’ The lighthearted exchange contained a serious offer. Mawapanga exhorted Katumba to have the bank second him to what was about to become Congo’s new government. Katumba craved influence but had foreseen a career in international business, not the chaos of Congolese government. Nonetheless, aged thirty-three, he headed home to take up Mawapanga’s invitation. His transformation into one of Africa’s most powerful men had begun.

As the rebels struggled to start governing after deposing Mobutu, Katumba impressed as an adviser in the finance ministry. He had been back in Congo less than a year when his phone rang. ‘Hello, may I speak with Katumba?’ said the voice on the line.

‘Yes, this is he.’

‘This is Kabila.’

Katumba had a friend with the same name and asked him what he wanted.

‘No,’ said the voice. ‘This is Laurent-Désiré Kabila.’15

The president, a fellow Katangan, told Katumba he wanted to meet him. A few weeks later Katumba stood before the corpulent guerrilla at the presidential palace. Following some brisk questioning about the young man’s background, the president said, ‘I want to name you governor of Katanga.’ According to his memoir, a stunned Katumba protested that he was utterly unqualified for what was one of the most influential positions in Congolese politics. But he could hardly refuse. The appointment was made public that evening. ‘Katanga is as big as France,’ Mawapanga, the finance minister, told his protégé. ‘If you can manage that, the sky’s the limit.’ He might have added that Katumba was being handed the keys to one of the world’s greatest vaults of minerals.

Kabila’s rebels-turned-rulers needed to generate money from Congo’s dilapidated mining industry for the twin purposes of resisting an invasion by their erstwhile Rwandan backers and making sure that they used what might prove a brief stint in power to bolster their personal finances. Oscar Mudiay, a senior civil servant in Kabila’s government, told me that the president received a minimum of $4 million each week delivered in suitcases by state-owned and private mining companies.16 Kabila’s government soon signed a flurry of mining and oil deals, with scant regard for due process. The regional coalition that had swept him to power had split into pro-Kabila and pro-Rwanda alliances, and Kabila needed to keep his foreign allies, principally Zimbabwe and Angola, sweet. One beneficiary of the deal-making was Sonangol, the Angolan state oil company controlled by the Futungo, with which the Congolese state formed a partnership.17 As governor of Katanga province, Katumba was perfectly placed to build his influence over the mining industry. ‘He was more intelligent than the others and got close to Gécamines,’ Oscar Mudiay recalled.

As he built a base for himself in Congo’s mining heartland, Katumba became a member of Kabila’s inner circle. He befriended the president’s son while they travelled together on sensitive diplomatic missions. Monosyllabic and withdrawn, Joseph Kabila had been thrown into the military when his father became the figurehead of the rebellion against Mobutu. He was prematurely promoted to general and, in name at least, appointed head of the army. In December 2000 Rwandan troops and anti-Kabila forces routed the Congolese army and its foreign allies at Pweto, Katumba’s hometown in Katanga. The Rwandans seized a valuable cache of arms, but there was another prize within their reach: Joseph Kabila was on the battlefield. As the Congolese army melted into frantic retreat and the high command took to its heels, Katumba received a call from the president: ‘Kiddo, find Joseph, my son.’18

Katumba raced to reach Joseph by phone and discovered he was alive and still free. Such were the straits of the government campaign that Katumba, according to his memoir, personally had to find fuel and take it to the airport for a plane to evacuate the president’s son.19 This was the moment that formed an unbreakable bond between Katumba and the younger Kabila.

Four weeks later one of Laurent Kabila’s bodyguards, an easterner who had been among the cohort of child soldiers in Kabila’s rebel army, approached the president and shot him three times at close range, for reasons that have been the subject of competing conspiracy theories ever since. In disarray, his senior officials decided to create a dynasty on the spot and summoned Joseph to Kinshasa to inherit the presidency. Mawapanga Mwana Nanga, the former finance minister who had brought Katumba back to Congo, was involved in the tense efforts to hold the government together after the assassination. ‘Joseph was a general – he did not know politics,’ Mawapanga told me. ‘So he called Katumba to come back and be his right-hand man and show him how to navigate the political waters.’

In four years Katumba had gone from a junior post in a Johannesburg bank to the side of Congo’s new president. He was appointed minister of the presidency and state portfolio, in charge of state-owned companies. In 2002 UN investigators appointed to study the illegal exploitation of Congo’s resources named him as one of the key figures in an ‘elite network’ of Congolese and Zimbabwean officials, foreign businessmen and organized criminals who were orchestrating the plunder of Congolese minerals under cover of war.20 ‘This network has transferred ownership of at least $5 billion of assets from the state mining sector to private companies under its control in the past three years with no compensation or benefit for the state treasury of the Democratic Republic of the Congo,’ the UN team wrote.

When the UN investigators recommended Katumba be placed under UN sanctions, he was shuffled out of his official post in Kabila’s government – and moved into the shadow state. He became the leading exponent of a system that Africa Confidential, the most comprehensive publication in English on the continent’s affairs, encapsulated: ‘Exercising power, from the late President Mobutu Sese Seko to the Kabila dynasty, has relied on access to secret untraceable funds to reward supporters, buy elections and run vast patronage networks. This parallel state coexists with formal structures and their nominal commitment to transparency and the rule of law.’21

I have heard people compare Katumba to Rasputin, Karl Rove and the grand viziers of the Ottoman Empire. Diplomats rarely met him. In photographs his eyes look penetrating, his face set in a permanent semifrown of calculation. One foreigner who found himself in the same room as Katumba described an impressive man, shrewd and gentlemanly, with a fondness for his own jokes. ‘He never spoke much,’ said Oscar Mudiay, the official who served under Laurent Kabila. ‘Just a glance.’

Katumba was like an elder brother to the young president. ‘Joseph Kabila put his total faith in Katumba,’ Olivier Kamitatu, an opposition politician who served for five years as planning minister in Kabila’s government, told me.22 ‘He was hugely intelligent. He knew how to run the political networks and the business networks. The state today is the property of certain individuals. Katumba’s work was to create a parallel state.’

On 15 October 2004, the residents of the Katangan mining town of Kilwa discovered what it meant to fall foul of Katumba’s looting machine. The previous day Alain Kazadi Makalayi, a twenty-year-old fisherman with delusions of grandeur, had arrived in Kilwa at the head of half a dozen ramshackle separatists and proclaimed the independence of Katanga.23 His call to arms attracted fewer than a hundred young followers. Realizing that a rebellion that could not even organize a radio broadcast was unlikely to last long and that the national army could not be far off, most of Kilwa’s inhabitants ran away.

The separatists posed a negligible threat, but they had dared to challenge the interests of the shadow state. Dikulushi, the copper mine that lay 50 kilometres outside the town, was linked to Katumba.

Anvil Mining, a small Australian outfit, had won the rights to mine the area in 1998 and began producing copper in 2002. According to a subsequent inquiry by the Congolese Parliament, the company was granted a twenty-year exemption from paying any taxes whatsoever.24 Katumba was a founding board member of Anvil’s local subsidiary, and his name appeared on the minutes of three board meetings between 2001 and 2004.25 Bill Turner, Anvil’s chief executive, denied that Katumba held any shares in the company; he said Katumba sat on the board as the government’s representative. But Turner admitted to a reporter from Australia’s ABC television that, as well as a few thousand dollars in director’s fees, the company paid some $50,000 a year to rent a compound Katumba owned in Lubumbashi, Katanga’s capital, for its headquarters.

After the young separatist convened a public meeting in Kilwa’s marketplace to proclaim his rebellion and declare that the days of Joseph Kabila and Katumba ‘pocketing money from the mines’ were over, the president ordered the regional military commander to retake the town within forty-eight hours.26 Troops had orders to ‘shoot anything that moved’, according to a UN inquiry into what followed.27

The soldiers arrived on Anvil Mining’s aircraft and made use of the company’s vehicles. They encountered scant resistance and suffered no casualties putting down the inept rebellion. Once the fighting was over they taught Kilwa a lesson.

Soldiers went from house to house, dispensing vengeance. At least one hundred people were killed. Some were forced to kneel beside a mass grave before being executed one by one. Among the dead were both insurgents and civilians, including a teenager whose killers made off with his bicycle. Kazadi, the hapless separatist leader, was said to have died of his wounds in the hospital. Soldiers who ransacked homes and shops carried their loot away in Anvil vehicles, which were also used to transport corpses, according to the UN investigation, claims the company denied.28

A decade later, in 2014, I asked Bill Turner about Anvil’s role in the Kilwa massacre. ‘Anvil were of course aware of the rebellion and the suppression of the rebellion in Kilwa in October 2004, having provided logistics to the DRC Military, under force of law,’ he told me, declining to elaborate on what those logistics were. But Turner told me he had not been aware of ‘allegations of war crimes or atrocities’ until an ABC reporter asked him about them in an interview seven months after the massacre. (He added that the interview was edited with the aim of ‘portraying Anvil and me in the worst possible light’.) ‘There have been multiple government enquiries in a number of countries, including a detailed Australian Federal Police investigation in Australia into those allegations,’ Turner continued in a letter responding to my questions. ‘None of those enquiries has found that there is any substance whatsoever to the allegations. In addition, there has been litigation instigated in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Western Australia and Canada, which has at least touched on the matters raised by you. In none of those cases have there been findings against Anvil.’29

The survivors’ representatives fought for years to hold those responsible for the Kilwa massacre to account, but they got nowhere. Katumba was untouchable. In 2009 a US diplomatic cable described him as ‘a kind of shady, even nefarious figure within Kabila’s inner circle, [who] is believed to manage much of Kabila’s personal fortune’.30 The cable was transmitting news that Katumba had stepped down from his latest formal position, heading Kabila’s majority in the national assembly. But it predicted – accurately – that his influence would remain.

In 2006 and 2007 two rebel groups and the Congolese army fought for control over Edouard Mwangachuchu’s coltan mine at Bibatama.31 The group that won out was arguably the most formidable rebel force in eastern Congo – quite an accolade, given the ferocity of the fighting that continued to erupt regularly despite the formal end of the war in 2003.

Known by its French acronym, CNDP, the Congress for the Defence of the People was the creation of Laurent Nkunda, a Tutsi renegade general and Seventh-Day Adventist pastor from North Kivu. Nkunda had fought with Rwanda against Laurent Kabila before joining the Congolese national army when it incorporated various warring factions under the 2003 peace deal. He rose to general before returning to the cause of rebellion – this time, his own.

The hills and forests around Nkunda’s hometown in North Kivu became his fiefdom, as the forces at his command swelled to eight thousand men (and children).32 A student of psychology, for a time he outwitted everyone, navigating with cunning the treacherous terrain in which Rwanda and Kinshasa jostled for influence with UN peacekeepers, arms dealers, local politicians and eastern Congo’s constellation of paramilitary groups.

For all Nkunda’s rhetoric – he spoke to a Financial Times reporter in 2008 of ‘a cry for peace and freedom’ – his operation was, in large measure and like many of its rivals, a money-making venture.33 Eastern Congo’s militias – not to mention the army itself – have many ways to bring in revenue, from taxing commercial traffic to ranching and trading in charcoal. But the mining trade is particularly lucrative and has the advantage of bringing in foreign currency that can buy arms.

The business arrangements of eastern Congo’s clandestine mineral trade reveal something else, something that undercuts the crass notion that the primitive hatreds of African tribes are the sole driver of the conflict. The two most important militias, the CNDP and the Forces Démocratiques de Libération du Rwanda (FDLR), are sworn enemies. The former’s stated reason to exist is to defend the Tutsis of eastern Congo from the latter, a cohort formed by the Hutu extremists who perpetrated the Rwandan genocide. Both also serve as proxies: Joseph Kabila has supported the FDLR to counter the influence that Paul Kagame’s Tutsi-led government in Rwanda exercises through the CNDP.

But as one easterner who has worked in both mining and intelligence told me, ‘Formally the groups are all enemies. But when it comes to making money and mining, they cooperate pretty well. War changes, but business goes on. The actors change, but the system stays – the links between the armed groups and the mines. The conflict goes on because it has its own financing: the mines and the weapons. It has its own economy.’34

On a Sunday afternoon in Goma I drank a beer beside a pool at a hotel with Colonel Olivier Hamuli. He is the spokesman of the Congolese armed forces and journalists regard him as one of the more accurate sources of information on the fighting, even if he avoids discussing the military’s own role in plunder and atrocities. An easterner, his convivial demeanour cannot mask the eyes of a man who has seen too much. When we met he was fielding call after call about clashes between Tutsi rebels and the army. The rebels had advanced to take strategic positions on the edge of Goma; the army and UN peacekeepers were preparing helicopter gunships for a counterattack.

‘The CNDP, the FDLR, they say they are fighting against bad governance. They are just mining. Even the FDLR, they are not trying to challenge the Rwandan government – they are here to mine. This is the problem of the war in the east,’ the colonel said.35 ‘It’s a war of economic opportunity. It’s not just Rwanda that benefits; it’s businessmen in the United States, Australia too.’ He brandished one of his incessantly buzzing mobile phones. ‘Smuggling goes on. Mobile phones are still being made. They need the raw materials one way or another.’

According to the UN panel of experts that tries to keep track of the links between eastern Congo’s conflict and the mineral trade, after Nkunda won the battle for the territory that contained Mwangachuchu’s mining operations, the warlord permitted the businessman to retain control of his mines in return for a cut of the coltan.36 Mwangachuchu told the UN team he paid 20 cents per kilo of coltan exported from his mines at checkpoints he suspected were run by the CNDP.37 That levy alone would have channelled thousands of dollars a year into the militia’s war chest. Altogether eastern Congo’s militias are estimated to have raked in something to the tune of $185 million in revenues from the trade in coltan and other minerals in 2008.38 The UN team also reported Mwangachuchu’s excuse for funding the militia: he told the team he had ‘no choice but to accept the presence of CNDP and carry on working at Bibatama, as he needs money to pay $16,000 in taxes to the government.’

To his supporters, Mwangachuchu is a well-meaning employer (of both Tutsis and other ethnicities) assailed by grasping militiamen. His supporters, none of whom wanted to be named when they spoke to me, described a legitimate businessman striving to introduce modern mining techniques in the face of turmoil and wrongheaded foreign interventions. Some well-informed Congolese observers are less inclined to give him the benefit of the doubt. One night in a Goma bar a senior army officer fumed with anger when I asked him about Mwangachuchu and other mining barons of North Kivu. He damned them all as war profiteers who preferred to pay a few dollars to rebel-run rackets than have a functioning state tax them properly. When I asked the easterner who has worked both on mining policy and in Congolese intelligence about Mwangachuchu’s claim that he had been forcibly taxed by the CNDP, he shot back, ‘It’s not a question of taxes. Mwangachuchu and the armed groups are the same thing.’

It is hard to see how Mwangachuchu could have established himself as a leading Tutsi businessman in the East without becoming intertwined with the armed groups. As well as seeking prosperity, Tutsis in eastern Congo have faced near-constant threats to their survival, most terrifyingly from the Rwandan Hutu génocidaires who roam the hills.

In 2011 Mwangachuchu stood as a candidate for CNDP’s political wing in the national assembly – and its foot soldiers helped guarantee his victory. They had been absorbed into the lawless ranks of Congo’s army under a shaky peace deal but retained their mining rackets and their loyalties.39 ‘The CNDP guys used every trick in the book to make sure he got through,’ said a foreign election observer who watched former CNDP rebels filling out ballot papers for Mwangachuchu after the polls had closed.40 Ex-CNDP fighters in the national army were observed brazenly intimidating voters in North Kivu, some of the most egregious abuses in a deeply flawed national election that secured Kabila a fresh term.41 According to a report to the Security Council by a UN group of experts, to ensure the support of the CNDP’s fighters, Mwangachuchu had paid off Bosco Ntaganda. Known as ‘The Terminator’, Ntaganda had replaced the deposed Laurent Nkunda three years earlier as the CNDP boss and brought his boys into the army even though he was wanted by the International Criminal Court for war crimes including murder, rape, conscripting child soldiers, and ethnic persecution.42 Despite overwhelming evidence of foul play and months of legal wrangling, Mwangachuchu’s election stood. Even before his victory was secure, Ntaganda named him president of the CNDP’s political party.

Mwangachuchu’s leadership was short-lived. A few months after the 2011 election Kabila’s government sought to strengthen its writ in the East by relocating the former CNDP militiamen who had been brought into the national army to postings elsewhere in the country, far from the East’s coltan, gold and tin mines. But the militiamen were not about to give that up without a fight. Several hundred mutinied under a new acronym, M23, short for March 23, the date of the 2009 deal that had brought them into the army. Rwanda, deeply involved in both eastern Congo’s military and mining networks, again provided covert support to the mainly Tutsi rebels as they advanced on Goma.43

In early May 2012 General James Kabarebe, the redoubtable Rwandan defence minister who had masterminded its military campaigns in Congo and surreptitiously commanded M23, called Mwangachuchu. He ordered him to support the rebels and pull the CNDP political party out of its alliance with Kabila.44 Mwangachuchu refused. Perhaps he feared that crossing Kabila would imperil his mining interests; perhaps he sensed that the new rebellion was doomed. A furious Kabarebe told Mwangachuchu that ‘a lightning bolt will strike you’. Within days he had been ousted as president of the CNDP’s political party.

But Mwangachuchu had chosen wisely. Western powers that had long turned a blind eye to Rwanda’s meddling in Congo ran out of patience and suspended aid. Bosco Ntaganda, the Tutsi warlord who had joined the mutiny, found himself under such mortal threat that he chose to take his chances in The Hague and turned himself in at the US embassy in Rwanda, from where he was sent to face justice at the International Criminal Court. At negotiations in Uganda between Kabila’s government and the M23 rebels, Mwangachuchu was part of the government delegation. The talks came to little, and in late 2013 Congolese forces, backed by a new UN force with a mandate to smash the rebel groups, routed the M23 rebels.

I asked Mwangachuchu to give me his own account. He declined. When I e-mailed him a list of questions, it was his lawyer who replied. Mwangachuchu, the lawyer wrote, ‘reminds you that there is a war on in this part of the country and he cannot afford at this stage to answer your questions.’ Mwangachuchu can claim to have played peacemaker – but only when it suits him. ‘He’s not a fighter; he’s a businessman,’ a former minister in Kabila’s government told me. ‘His loyalties are not so strong – except to his business.’

Our two-jeep convoy slowed as it approached a roadblock deep in the tropical forests of one of eastern Congo’s national parks. Manning the roadblock were soldiers from the Congolese army, theoretically the institution that should safeguard the state’s monopoly on the use of force but, in practice, chiefly just another predator on civilians. As my Congolese companions negotiated nervously with the soldiers, I stepped away to take advantage of a break in a very long drive and relieve myself, only to sense someone rushing toward me. Hurriedly zipping up my fly, I turned to see a fast-approaching soldier brandishing his AK47. With a voice that signified a grave transgression, he declared, ‘It is forbidden to piss in the park.’ Human urine, the soldier asserted, posed a threat to eastern Congo’s gorillas. I thought it best not to retort that the poor creatures had been poached close to extinction by, among others, the army, nor that the park attracted far more militiamen than gorilla-watching tourists.

My crime, it transpired, carried a financial penalty. My companions took the soldier aside, and the matter was settled. Perhaps they talked him down, using the presence of a foreign journalist as leverage. Perhaps they slipped him a few dollars. As we drove away it occurred to me that we had witnessed the Congolese state in microcosm. The soldier was following the example set by Kabila, Katumba, Mwangachuchu and Nkunda: capture a piece of territory, be it a remote intersection of potholed road, a vast copper concession, or the presidency itself; protect your claim with a gun, a threat, a semblance of law, or a shibboleth; and extract rent from it. The political economy of the roadblock has taken hold. The more the state crumbles, the greater the need for each individual to make ends meet however they can; the greater the looting, the more the authority of the state withers.

Leaving the roadblock behind, we bounced along the pitted tracks that lead into the interior of South Kivu province. It was late 2010, and a joint offensive against Hutu rebels by Congolese and Rwandan forces and their allied militias had driven masses of civilians from their farmsteads. Kwashiorkor, or severe acute malnutrition in children, was rife.

The lone hospital in Bunyakiri serves 160,000 people. It has no ambulance and no electricity, making it almost impossible after nightfall to find a vein for an injection. The rusting metal of its roof is scarcely less rickety than the surrounding mud huts. When I visited, medicine was in short supply, the army having recently ransacked the hospital. There was no mobile phone reception, an irony in a part of the world whose tantalum is crucial in making the devices.

The hospital’s pediatric ward had fourteen beds. At least two mothers sat on each, cradling their babies. On one, Bora Sifa regarded her surroundings warily. Two years earlier a raiding party from the FDLR, the militia formed by the perpetrators of the Rwandan genocide, had descended on her village in search of loot to supplement the income from their mining operations. The raiders ordered Bora’s husband to gather up what they wanted. ‘They forced him to carry all the things away into the forest,’ Bora told me. ‘Then they killed him.’

Bora fled and a stranger in another village took her in, allowing her and her children to live in an outhouse. Now twenty, she made about a dollar a day helping to cultivate cassava, a root crop that fills empty bellies but has little nutritional value. Five days ago she had brought her son, Chance, to the hospital. ‘He wasn’t growing,’ Bora said. ‘I wasn’t making enough milk.’ Like many malnourished children, Chance’s features had aged prematurely. His eyes were sunken, his hair receding.

At any given moment since the start of Congo’s great war in 1998, between 1 million and 3.5 million Congolese have been adrift like Bora. The vast majority are in the East, driven from mining areas or the shifting frontlines of multiple interwoven conflicts. In 2013 2.6 million of Congo’s 66 million people were ‘internally displaced’, as refugees who have remained in their country are known in the jargon of human catastrophe, making up one in ten of the worldwide tally.45 Many end up in flimsy bivouacs fashioned from tarpaulins bearing the brands of assorted relief agencies; others appeal to the solidarity of their fellow Congolese, which persists despite the myriad fissures that war, desperation and ethnicity have opened between them. That solidarity can only do so much in a country where two-thirds lack sufficient food. Uprooted, Congo’s wandering millions starve.

With the help of the hospital’s tireless doctor and a French charity, Chance was recovering.46 Few others shared his fortune. Further up the road I visited a hilltop clinic beside a school in the town of Hombo Sud. One by one, dozens of emaciated children were being dangled from weighing scales and checked for telltale signs of severe malnutrition: oedema (a buildup of fluids in the legs) and arms with a circumference of less than 10.5 centimetres.

Anna Rebecca Susa, a bundle of spindles in a pink skirt emblazoned with the word ‘Princess’, was dangerously underweight. The special measuring tape showed red when a medic pulled it tight round her arm. Her belly was swollen beneath fleshless ribs, her hair reduced to a faint frizz. At five, she could not understand what was happening to her, but her big eyes were full of anxiety, as though she could sense that her body was failing. She could not keep down a sachet of the peanut paste that can do wonders for malnourished children and was sent home with more in the hope her stomach would settle. Her father, Lavie, invited me back to his home, an outhouse belonging to a distant relative where Lavie, his wife, and their four children had lived since they fled rebel attacks on their home village two years previously.

The signature falsetto guitar of Congolese music drifted over the jagged rooftops of the tiny metal shacks sprayed across the slopes. Lavie’s wife, whose wedding ring he had fashioned from a plastic bottle top, was out foraging for leaves. Anna fell asleep on the shack’s lone bed. Her younger brother, Espoir, tottered around, oblivious to his sister’s plight.

A few weeks later I got in touch with the clinic’s medics to ask after Anna. When she had kept throwing up the peanut paste, the French charity had driven her to the hospital at Bunyakiri. By then there was little anyone could do. Her immune system destroyed by malnutrition, she died of an infection.

The heavens opened the day they buried Augustin Katumba Mwanke. The Congolese establishment sheltered under marquees in Kinshasa before the coffin that sported an enormous floral garland.47 In a black suit and black shirt Joseph Kabila arrived amid a phalanx of bodyguards manoeuvring to keep an umbrella over his head. It was a rare public appearance for a reclusive president said to have spent his early years in office in the company of video games. His face was expressionless. Barely two months had passed since he had rigged his way to victory in the presidential election, securing a second five-year term. Now the mastermind behind both his power and his wealth was gone. The previous day, 12 February 2012, the American pilot of the jet carrying a group of Kabila’s senior officials to Bukavu by Lake Kivu had misjudged the landing. Katumba’s last moments came as the aircraft veered off the runway and smashed into a grassy embankment. He was forty-eight.

One other guest at the funeral stood out. He was the lone white face in the front row. Kabila clasped his hand. The burly, bearded man in a yarmulke, the Jewish skullcap, was Dan Gertler. He was the all-important intersection between the shadow state that controlled access to Congo’s minerals and the multinational mining companies that coveted them.

The grandson of one of the founders of Israel’s diamond exchange, in his early twenties Gertler set forth to seek his own fortune. He went to Angola, then still deep in civil war and a rich source of diamonds. But another Israeli, Lev Leviev, had already staked a strong claim there. Gertler arrived in Congo in 1997, days after Laurent Kabila had overthrown Mobutu. An ultra-orthodox Jew, he was introduced by a rabbi to Joseph Kabila, newly installed as the head of the Congolese army.48 The younger Kabila and Gertler had much in common. Each stood in the shadow of his elders, carrying a heavy burden on young shoulders into the cauldron of Congolese warfare and politics. They became firm friends.

Gertler soon discovered the value of his friendship with the president’s son. Kabila Sr was in urgent need of funds to arm his forces against Rwandan and Ugandan invaders and to butter up his allies for the fight.49 When Joseph took his new friend to meet his father, the president told the young Israeli that if he could raise $20 million without delay, he could have a monopoly to buy every diamond mined in Congo. Gertler cobbled together the cash and was granted the monopoly.

Not for the last time, an arrangement that suited Gertler and the Kabila clan hardly served the interests of the Congolese people. ‘It wasn’t a good deal for us,’ Mawapanga Mwana Nanga, then the finance minister, told me. ‘We should have opened the market to the highest bidder.’50 UN investigators declared that Gertler’s diamond monopoly had been a ‘nightmare’ for Congo’s government and a ‘disaster’ for the local diamond trade, encouraging smuggling and costing the treasury tax revenue.51 It could not last. After Joseph Kabila succeeded his assassinated father in 2001, the monopoly was cancelled under pressure from foreign donors.52

Gertler was not deterred. He re-established a commanding position in the Congolese diamond trade by arranging to buy stones from the state-owned diamond miner and began to turn his attention to the far bigger prize: the copper and cobalt of Katanga, where production and prices would rise dramatically as Asian demand for base metals soared. His most important asset – his bond with the new president – was intact. ‘Gertler showed that he could help the family and, in return, they said, “We can do business with you,”’ a diplomat who spent years watching Gertler’s exploits in Congo told me. ‘Kabila can only keep himself in power with the help of people like Gertler: it’s like an insurance mechanism – someone who can get you money and stuff when you need it.’

Over the years that followed, Gertler cultivated Katumba too, even inviting him to a party on a yacht in the Red Sea that included a performance by Uri Geller, the Israeli illusionist and self-proclaimed psychic.53 In a reverie of gratitude to Gertler, in the final pages of his posthumously published memoir Katumba wrote that ‘in spite of all our seeming differences, I am proud to be the brother you never had.’54

The trio of Kabila, Katumba and Gertler was unassailable. ‘It’s like an exclusive golf club,’ one of Kabila’s former ministers told me. ‘If you go and say, “The founders are cheating,” they’re going to say: “And who the hell are you?”’55 Gertler’s role in this exclusive club was manifold. ‘It’s an amalgam – business, political assistance, finance,’ said Olivier Kamitatu, who became an opposition legislator after his five-year stint as Kabila’s planning minister.56 Gertler’s particular contribution was to build a tangled corporate web through which companies linked to him have made sensational profits through sell-offs of some of Congo’s most valuable mining assets. ‘The line between the interests of the state and the personal interests of the president is not clear,’ Kamitatu told me. ‘That is the presence of Gertler.’

Since he first rode to Laurent Kabila’s rescue with $20 million to fund the war effort, Gertler has proved himself invaluable to Congo’s rulers. Katumba wrote in his memoir that Gertler’s ‘inexhaustible generosity, and the extreme efficiency of his assistance, have been decisive for us in the most crucial moments.’57 Deals in which he was involved are said to have helped finance Joseph Kabila’s 2006 election campaign.58 Kamitatu told me that Gertler had helped Kabila win that election and said he had also come up with cash for the military campaign against Laurent Nkunda’s rebels in the East. I asked Gertler’s representatives whether he had assisted Kabila at these moments and during the 2011 elections. They did not respond. Gertler has, however, denied that he has underpaid for Congolese mining assets. ‘The lies are screaming to the heavens,’ he told a reporter from Bloomberg in 2012.59

Kamitatu, who is the son of one of Congo’s independence leaders and trained in business before a political career that began as a senior figure a rebel group during the war, sees the shadow state as the root of his nation’s failure to escape poverty. ‘You can’t develop the country through parallel institutions. Every infrastructure project you undertake is not done through a strategic vision but with a view to the personal financial results,’ he told me as we sat at his house in Kinshasa in 2013. Politics and private business have fused, Kamitatu believed. Winning a presidential election costs tens of millions of dollars, and the only people with that kind of money are the foreign mining houses. ‘I am extremely worried about a political system where the voters are starving and the politicians buy votes with money from natural resource companies,’ Kamitatu said. ‘Is that democracy?’

Dan Gertler’s Congolese mining deals have made him a billionaire. Many of the transactions in which he has played a part are fiendishly complicated, involving multiple interlinked sales conducted through offshore vehicles registered in tax havens where all but the most basic company information is secret. Nonetheless, a pattern emerges. A copper or cobalt mine owned by the Congolese state or rights to a virgin deposit are sold, sometimes in complete secrecy, to a company controlled by or linked to Gertler’s offshore network for a price far below what it is worth. Then all or part of that asset is sold at a profit to a big foreign mining company, among them some of the biggest groups on the London Stock Exchange.

Gertler did not invent complexity in mining deals. Webs of subsidiaries and offshore holding companies are common in the resource industries, either to dodge taxation or to shield the beneficiaries from scrutiny. But even by the industry’s bewildering standards, the structure of Gertler’s Congo deals is labyrinthine. The sale of SMKK was typical.60

SMKK was founded in 1999 as a joint venture between Gécamines, Congo’s state-owned mining company, and a small mining company from Canada.61 SMKK held rights to a tract of land in the heart of the copperbelt. It sits beside some of the planet’s most prodigious copper mines, making it a fair bet that the area the company’s permits cover contains plentiful ore. Indeed, Gécamines had mined the site in the 1980s before Mobutu’s looting drove the company into collapse.62 After a string of complicated transactions beginning in November 2007, involving a former England cricketer, a white crony of Robert Mugabe, and assorted offshore vehicles, 50 per cent of SMKK ended up in the hands of Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation (ENRC), whose oligarch owners had raised a few eyebrows in the City of London in 2007 when they obtained a London Stock Exchange listing for a company they had built from privatized mines in Kazakhstan.63 The Congolese state, through Gécamines, still owned the remaining 50 per cent of SMKK.

Toward the end of 2009 ENRC bought an option, only made public months later, to purchase the 50 per cent it did not already own. The strange thing was that ENRC did not buy that option from the owner of the stake, state-owned Gécamines, but from a hitherto unknown company called Emerald Star Enterprises Limited.64 Emerald Star was incorporated in the British Virgin Islands, one of the most popular secrecy jurisdictions, shortly before it struck this agreement with ENRC, which suggests that it was set up for that specific purpose.65 There is nothing in Emerald Star’s registration documents to show who owns it. But other documents related to the deal would later reveal the identity of its principal owner, Dan Gertler’s family trust.66

At this stage all Gertler had was a deal to sell to ENRC a stake in SMKK that he did not yet own. That was soon rectified. On 1 February 2010, Gertler’s Emerald Star signed an agreement with Gécamines to buy the Congolese state’s 50 per cent share in SMKK for $15 million.67 ENRC duly exercised its option to buy the stake by buying Emerald Star for another $50 million on top of the $25 million it had paid for the option. The interwoven deals were done and dusted by June 2010.68 All the corporate chicanery masked a simple fact: the Congolese state had sold rights to a juicy copper prospect for $15 million to a private company, which immediately sold the same rights on for $75 million – a $60 million loss for the state and a $60 million profit for Gertler.

The Congolese people were not the only losers in the SMKK deal. ENRC’s would seem to have suffered too. When it bought the first 50 per cent of SMKK, ENRC had also acquired a right of first refusal should Gécamines decide to sell the other half.69 That meant that ENRC could have bought the stake when it was offered to Dan Gertler’s company for $15 million. Instead, it paid $75 million a few months later, once the stake had first passed to Gertler’s offshore vehicle. ENRC has not disclosed the terms of its right of first refusal and did not reply to my questions about it. Perhaps there was some stipulation in it that meant buying the stake directly from Gécamines would have been more expensive for ENRC than buying it via Gertler. But based on the details that have emerged, it is hard to see how the oligarch founders of ENRC thought the SMKK manoeuvre was in the best interests of the rest of the investors who had bought shares in the company when it floated in London.

ENRC was a member of the FTSE 100, the prestigious list of the UK’s biggest listed companies, in which pension funds invest savers’ money. Investors who bought shares when ENRC listed some of its stock in December 2007 paid £5.40 a share, raising £1.4 billion for the company. Over the six years that followed, ENRC’s boardroom was a scene of unceasing turbulence, as the oligarch founders continued to exert their influence over a company that was supposedly subject to British governance rules for listed corporations.70 ENRC snapped up assets in Africa, including SMKK, and struck other deals with Gertler in Congo. The Serious Fraud Office was in the middle of an investigation (still active at the time of writing) into ENRC’s activities in Africa and Kazakhstan – and its share price was sliding precipitously downward – when the oligarchs announced that they planned, with the help of the Kazakh government, to buy back the stock they had listed in London, thereby taking the company private again.71 The offer was valued at £2.28 a share – less than half of what investors who bought in at the start had paid for them.72

If some British pension funds and stock-market dabblers felt burned by their investments in ENRC, their losses were relatively easy to bear compared with those that Gertler’s sweetheart deals have inflicted on Congo. The best estimate, calculated by Kofi Annan’s Africa Progress Panel, puts the losses to the Congolese state from SMKK and four other such deals at $1.36 billion between 2010 and 2012.73 Based on that estimate, Congo lost more money from these deals alone than it received in humanitarian aid over the same period.74 So porous is Congo’s treasury that there is no guarantee that, had they ended up there, these revenues would have been spent on schools and hospitals and other worthwhile endeavours; indeed, government income from resource rent has a tendency to add to misrule, absolving rulers of the need to convince electorates to pay taxes. But no state can fulfil its basic duties if it is broke. Between 2007 and 2012 just 2.5 per cent of the $41 billion that the mining industry generated in Congo flowed into the country’s meagre budget.75 Meanwhile, the shadow state flourishes.

Since at least 1885, when Congo became the personal possession of Belgium’s King Leopold II, outsiders have been complicit in the plunder of Congo’s natural wealth. King Leopold turned the country into a commercial enterprise, producing first ivory then rubber at the cost of millions of Congolese lives. In 1908 Leopold yielded personal ownership of Congo to the Belgian state, which, keen to retain influence over the mineral seams of Katanga following independence in 1960, encouraged the region’s secessionists, helping to bring down the liberation leader Patrice Lumumba in a CIA-sponsored coup that ushered in Mobutu, who became one of the century’s most rapacious kleptocrats.76 Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush welcomed him warmly to Washington. Only once his usefulness expired after the end of the Cold War did the United States abandon Mobutu to flee from Laurent Kabila’s advancing rebels.

In the era of globalization the foreign protagonists in Congo’s looting machine are not monarchs or imperial states but rather tycoons and multinationals. As well as the likes of Dan Gertler, there are the companies that do business with him. ENRC is one. Another is Glencore, the giant commodity trading house based in the Swiss town of Zug, which listed its shares on the London Stock Exchange in 2011, immediately becoming one of the UK’s biggest listed companies. In 2010 and 2011 Glencore was involved in transactions in which, according to calculations by Kofi Annan’s Africa Progress Panel, the Congolese state sold mining assets to companies connected to Gertler for hundreds of millions of dollars less than they were worth.77 (Both ENRC and Glencore insist there has been nothing improper in their Congolese dealings.78)

From multibillion-dollar copper deals in Katanga to smuggling rackets shifting coltan out of the East, Congo’s looting machine extends from the locals who control access to the mining areas, via middlemen to traders, global markets and consumers. During the war UN investigators described companies trading minerals as ‘the engine of the conflict’.79 A senior Congolese army officer remembered Viktor Bout, a notorious KGB agent turned arms dealer who was implicated in the illicit coltan trade – and whose exploits inspired the 2005 film Lord of War – dropping in to do business.80 ‘He did terrible things here,’ the officer told me.81 The trade in minerals from eastern Congo spans the globe. In 2012, according to official records, North Kivu’s declared exports of raw minerals went to Dubai, China, Hong Kong, Switzerland, Panama and Singapore.

When Wall Street nearly imploded in 2008, triggering economic havoc far beyond Manhattan, the world was reminded of the extent of the damage that a complex cross-border network combining financial, economic and political power can do. The reforming legislation in the aftermath of the crisis dealt mostly with the financial quackery that had grown rife in US banks. But toward the end of the 848-page Dodd–Frank Act of 2010 was an item that had nothing to do with subprime mortgages or liquidity ratios. ‘It is the sense of Congress that the exploitation and trade of conflict minerals originating in the Democratic Republic of the Congo is helping to finance conflict characterized by extreme levels of violence in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo,’ read a clause in the Act that responded to years of pressure from campaigners. In the future companies using coltan and other resources from Congo in their products would have to submit to US regulators a report on their supply chain, signed off by an independent auditor, demonstrating that they were not funding armed groups. Some six thousand companies would be affected, among them Apple, Ford and Boeing.82

Few could fault the sentiment. But the legislation was drafted in Congress, not Congo. It backfired. For one thing, the definition of ‘armed groups’ left out the Congolese army, which has been responsible for looting and wanton violence. Then there was the practical difficulty of tracking supply chains in a war zone. When the Dodd–Frank Act passed, many buyers of Congolese minerals simply took their business elsewhere, reinforcing a temporary ban on mineral exports imposed by Joseph Kabila in response to pressure to curtail the turmoil in the East.

A score of ‘conflict-free’ certification schemes have sprung up, some connected to Dodd–Frank, some to Congolese initiatives, and some to industry efforts to wipe the stigma from their products. In April 2013 an independent German auditor who had spent five days at Edouard Mwangachuchu’s coltan mines concluded that ‘with the evidence presented there was no indication that there are armed groups involved in mining’.83 The bigger militias had pulled back from Mwangachuchu’s corner of North Kivu; M23, the most threatening armed group of the day, was camped close to the Ugandan border, away from the main mining areas.

I wanted to see for myself whether the link between eastern Congo’s minerals and its conflict was loosening. I asked to visit Mwangachuchu’s mines. He was out of town, and his company declined to grant me access. But I knew that a cooperative of informal miners was also mining the area, the subject of years of dispute with Mwangachuchu. On the three-hour drive from Goma we passed a settlement nestled in a bend in a valley that had served as the base for Laurent Nkunda’s CNDP rebels. Further along was a camp for refugees displaced by the M23 conflict. At the metal barriers marking the entrance to each village, young men flagged us down and suggested they might be due payment. Children, no older than five, had imitated their elders and crafted a makeshift roadblock of rocks and half a yellow water-canteen. They scampered from the road as approaching vehicles failed to slow.

Another refugee camp marked the start of Rubaya, the mining town at the foot of the hills that Mwangachuchu and the informal miners exploit. Toddlers with bloated bellies, the signature of malnutrition, tottered at the road’s verge. The town itself boasted more robust dwellings than the makeshift tents of the displaced. Mining money had even allowed the construction of a few sturdy wooden houses. Rows of cassava tubers lay whitening in the sun. The whole town sounded as though it were wailing, so numerous were its infants, a chorus pierced by the occasional squawk of a cockerel. A tattered Congolese flag flapped from a skinny tree trunk.

After an hour waiting to pay our respects to the town administrator – during which, a local activist whispered in my ear, the mining bosses were checking that there were not too many children at work for their visitor to see – my Congolese companions and I began our ascent to the summit. Red dust devils swirled around us as we climbed. A local man who worked to get children out of the mines pointed across a valley to the village where he had been one of the few survivors of a revenge massacre of Hutus by Rwandan invaders in 1997.

Porters with white sacks on their heads cascaded down the unpaved paths from the peak, throwing up clouds of red-brown dust. Each sack contained up to 25 kilograms of rock hewn from the mountain. The porters’ haste was a matter of economics: they were paid 1,000 Congolese francs per trip (about $1) and had to wash and sift their cargo in the stream at the bottom before it began the long trip toward the border or the buying houses of Goma.

Most of the incipient certification schemes for Congolese minerals work by tagging sacks of ore as they emerge from the mine to certify their provenance, imitating the Kimberley Process, which was designed to stem the flow of ‘blood diamonds’. The idea is to prevent belligerents getting around embargoes by passing off their minerals as originating from another mine or smuggling them across borders to allow Congolese coltan to be branded as Rwandan or Angolan diamonds as Zambian. But on this hillside there was not a tag in sight. One local, a peace campaigner who had come along for the climb and who kept his distance from the mining bosses leading the ascent, told me that some of the coltan extracted here was crossing the nearby border into Uganda clandestinely. That took it right through the territory of M23 rebels.

The slope grew steeper. The earth underfoot gave way like a sand dune. Finally a peak of jagged rock emerged, a giant fossilized sponge of warrens that the miners had dug by hand. About two thousand miners, all in Wellington boots, many bearing spades and picks, swarmed among the pits and trenches, some delving as deep as 15 metres into the ground with only rudimentary props to keep the sides from burying them alive. Some looked decidedly younger than eighteen. One was clearly baffled by the white-skinned visitor whose hair was longer than the standard Congolese buzz cut. ‘He has the voice of a man,’ the young miner intoned with consternation to one of my companions, ‘but the hair of a woman.’

On the next hill over we could make out Mwangachuchu’s mine. All this territory lay under his concession, but the informal miners had enough political clout to carry on regardless of his protests, in part thanks to ethnic manoeuvring by the cooperative’s Hutu leadership against the Tutsi Mwangachuchu. The cooperative had resisted Mwangachuchu’s repeated attempts to turf them off his land, challenging the validity of his claim. Mwangachuchu has countered by trying to oblige the informal miners to sell all their production through his company, without which it would be impossible for him to prove that minerals from the concession were not funding militias.

The chief miner, Bazinga Kabano, a well-dressed man with a long walking cane and a penchant for bellowing at his subordinates, told me that when the CNDP controlled the area the miners’ association used to pay the rebels a $50 fee to be allowed to dig. But he was keen to paint his industry not as an engine of war but as a path to betterment. He explained that some of the miners graduated to be négociants, the intermediaries who buy coltan at the mine and sell it on to the comptoirs that export it. Surveying the teeming hilltop, he declared, ‘We are helping them to live their dreams.’

I wandered off to talk to some miners out of earshot of the boss. Kafanya Salongo bore a passing resemblance to a meerkat as his blinking head popped out of a hole in the ground. He was short, slim and strong, ideal for a human burrower. He churned out one hundred sacks worth of rock a day, and that brought in $9. From that he had to find the $25 each miner must pay the bosses every month for the privilege of digging. ‘It’s not enough for the family,’ he told me. ‘I can afford some food and some medicine, but that’s it.’ At thirty-two, he had a wife and two sons. He laughed in the face of danger. ‘Yeah, it looks dangerous, but we know how to construct the shafts, so it’s fine.’

It is easy to scoff at the boss’s notion that these miners are digging toward their dreams. The work is gruelling and perilous. The official statistics recorded twenty deaths in mining accidents in North Kivu in 2012, six of them at an adjacent mine worked by the cooperative. The authorities noted that it is ‘very possible’ that not all deaths were reported. But by local standards the miners’ wages amount to big bucks. Some splash their pay on booze and hookers; some build better houses.

Kabila’s mining ban and the boycott prompted by the Dodd–Frank Act pitched thousands of eastern Congolese miners out of work. The World Bank has estimated that 16 per cent of Congo’s population is directly or indirectly engaged in informal mining, which accounts for all but a fraction of the industry as measured by employment;84 in North Kivu in 2006 mining revenue provided an estimated two-thirds of state income.85 But revenues to the provincial government’s coffers fell by three-quarters in the four years before 2012, in part because of what officials called the ‘global criminalization of the mining sector’ of eastern Congo. The state’s loss is the smugglers’ gain: when the official routes are closed, the clandestine trade picks up the slack.

By the middle of 2013 Kabila’s ban had been partially relaxed, and previously blacklisted comptoirs in Goma had reopened. A dozen mines in North Kivu that the government deemed to be unconnected to armed groups had been ‘green-lighted’ to export. But Emmanuel Ndimubanzi, the head of North Kivu’s mining division, told me that not a single mine was tagging its output so that buyers could identify the mine at which it had originated. ‘Tagging is very expensive,’ he said. ‘We don’t have the partners to pay for it.’ In what might have been a line from Catch-22, he added, ‘Certification can only happen with better security.’

Regional initiatives are increasingly tracking shipments of coltan and other ores, even if North Kivu is lagging behind. Some campaigners have welcomed what appears to be a significant reduction in the documented connections between militias and mining sites as a result of certification efforts and a UN-backed offensive against the armed groups.86 Gradually Western-based electronics groups are drawing up lists of approved smelters that can demonstrate that their metals come from mines that do not benefit Congolese militias, although the campaign group Global Witness warned in 2014 that the first supply-chain reports, which US companies buying Congolese minerals are now required to submit to regulators, ‘lack substance’.87 The German Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources has developed ‘fingerprinting’ technology that can trace a shipment of ore back to the mine from which it was extracted. This technology could, if comprehensively applied, prevent the entry into the international market of minerals from militia-controlled mines, provided that it were matched with an intelligence-gathering programme to keep tabs on all the militias’ mining operations.

It appears unlikely that the certification schemes will ever reliably cover the whole of eastern Congo’s mining trade. Clean miners have been squeezed, as the retreat of Western buyers has let Chinese comptoirs gain a near-monopoly on Congolese coltan, allowing them to dictate prices. The efforts to impose some control on the mineral trade might trim the income of the armed groups, but it does so at the cost of weakening the already precarious livelihoods of eastern Congo’s diggers and porters and their dependents. In a land ruled by the law of the roadblock, such initiatives can look quixotic. As Aloys Tegera of Goma’s Pole Institute, one of eastern Congo’s most astute commentators, writes, ‘Without a Congolese state capable of playing its role in controlling and running affairs, how can the minerals of Kivu be de-criminalised?’88

In the run-up to the 2011 elections and during the months that followed, the SMKK transactions and other similar ones effectively transferred hundreds of millions of dollars from the state to a close personal friend of a president. Dan Gertler has doubled as an emissary for the president, conducting diplomatic missions to Washington and Rwanda. ‘The truth is, during our very difficult times, there were investors who came and left and others who braved the hurricane,’ Kabila has said of Gertler.89 ‘He’s one of those.’ Kabila might have added that some of those who left did so when their assets were confiscated – and, in some cases, handed to Gertler.90

Gertler maintains that, far from being a predator, he is among Congo’s greatest benefactors. He and his representatives point out, with some justification, that unlike the most egregious asset-flippers, who do nothing beyond using bribes and connections to win mining rights before selling them on, Gertler’s operations in Congo actually produce minerals, and lots of them. His company, the Fleurette Group, says it has invested $1.5 billion ‘in the acquisition and development of mining and other assets in the DRC’, that it supports twenty thousand Congolese jobs, and that it ranks among the country’s biggest taxpayers and philanthropists.91 Gertler himself has said his work in Congo is worthy of a Nobel Prize.92

Katumba’s death sent a tremor through Kabila’s regime. Would-be investors whose only contract was an understanding they had reached with Katumba evaporated after the plane crash. But the president and Gertler, brothers in spirit, have maintained the shadow government that Katumba helped to construct. Gertler has branched out into oil, prospecting promising new sites at Lake Albert. As for Kabila, he must now decide whether to run in the next elections, due in 2016. To do so he would need to induce the national assembly to change the constitution and remove the two-term limit for presidents, then conduct what one election monitor at the 2011 polls told me would need to be ‘a huge rigging operation’ to overcome the electorate’s outrage. To pull off such an expensive task, Kabila would need to ratchet up the looting machine once again.