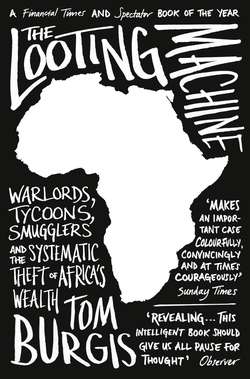

Читать книгу The Looting Machine: Warlords, Tycoons, Smugglers and the Systematic Theft of Africa’s Wealth - Tom Burgis, Tom Burgis - Страница 6

Author’s Note

ОглавлениеIN LATE 2010 I started to feel sick. At first I put the constant nausea down to a bout of malaria and a stomach bug I’d picked up during a trip a few months earlier to cover an election in Guinea, but the sickness persisted. I went back to the UK for what was meant to be a week’s break before wrapping up in Lagos, the Nigerian megacity where I was based as the Financial Times’s west Africa correspondent. A doctor put a camera down my throat and found nothing. I stopped sleeping. I jumped at noises and found myself bursting into tears. At the end of the week I was walking to a shop to buy a newspaper for the train ride to the airport when my legs gave way. I postponed my flight and went to another doctor, who sent me to a psychiatrist. In the psychiatrist’s office I started to explain that I was exhausted and bewildered, and I was soon sobbing uncontrollably. The psychiatrist told me I had severe depression and that I should be admitted to a psychiatric ward immediately. There I was put on diazepam, a drug for anxiety, and antidepressants. After a few days in the hospital it became apparent that there was something else tormenting me in tandem with depression.

Eighteen months earlier I had travelled from Lagos to Jos, a city on the fault line between Nigeria’s predominantly Muslim north and largely Christian south, to cover an outbreak of communal violence. I arrived in a village on the outskirts not long after a mob had set fire to houses and their occupants, among them children and a baby. I took photographs, counted bodies, and filed my story. After a few days trying to understand the causes of the slaughter, I set off for the next assignment. Over the months that followed, when images of the corpses flashed before my mind’s eye, I would instinctively force them out, unable to look at them.

The ghosts of Jos appeared at the end of my hospital bed. The women who had been stuffed down a well. The old man with the broken neck. The baby – always the baby. Once the ghosts had arrived, they stayed. The psychiatrist and a therapist who had worked with the army – both of them wise and kind – set about treating what was diagnosed as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). A friend of mine, who has seen his share of horrors, devised a metaphor through which to better understand PTSD. He compares the brain to one of those portable golf holes with which golfers practise their putting. Normally the balls drop smoothly into the hole, one experience after another processed and consigned to memory. But then something traumatic happens – a car crash, an assault, an atrocity – and that ball does not drop into the hole. It rattles around the brain, causing damage. Anxiety builds until it is all-consuming. Vivid and visceral, the memory blazes into view, sometimes unbidden, sometimes triggered by an association – in my case, a violent film or anything that had been burned.

Steadfast family and friends kept me afloat. Mercifully, there were moments of bleak humour during my six weeks on the ward. When the BBC presenter welcoming viewers to coverage of the wedding of Prince William and Kate Middleton declared, ‘You will remember where you were on this day for the rest of your life,’ the audience of addicts and depressives in the patients’ lounge broke into a chorus of sardonic laughter and colourful insults aimed at the screen.

The treatment for PTSD is as simple as it is brutal. Like an arachnophobe who is shown a drawing of a spider, then a video of one, then gradually exposed to the real thing until he is capable of fondling a tarantula, I tried to face the memories from Jos. Armed only with some comforting aromas – chamomile and an old, sand-spattered tube of sunscreen, both evocative of happy childhood days – I wrote down my recollections of what I had seen, weeping onto the paper as my therapist gently urged me on. Then, day after day, I read what I had written aloud, again and again and again and again.

Slowly my terror eased. What it left behind was guilt. I felt I ought to suffer as those who died had – if not in the same way, then somehow to the same degree. The fact that I was alive became an unpayable debt to the dead. Only after months had passed came a day when I realized that I had to choose: if I were on trial for the slaughter at Jos, would a jury of my peers – rather than the stern judge of my imaginings – find me guilty? I chose peace, to let the ghosts rest.

It was not, however, a complete exoneration. I had reported that ‘ethnic rivalries’ had triggered the massacres in Jos, as indeed they had. But rivalries over what? Nigeria’s 170 million people are mostly extremely poor, but their nation is, in one respect at least, fabulously wealthy: exports of Nigerian crude oil generate revenues of tens of billions of dollars each year.

I started to see the thread that connects a massacre in a remote African village with the pleasures and comforts that we in the richer parts of the world enjoy. It weaves through the globalized economy, from war zones to the pinnacles of power and wealth in New York, Hong Kong and London. This book is my attempt to follow that thread.