Читать книгу Beat Space - Tommaso Pincio - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление7.

A few days before departing for the Void, Jack Kerouac, accompanied by his friend Neal Cassady, entered a bookstore to buy a stellar atlas. “You can check it out in your downtime,” Neal had said. Actually, what he said was slightly different, but Jack, who was crazy about the way Neal talked, let his friend’s words wash over him without really trying to grasp any deeper meaning. He was happy to get the basic idea, listening to the undercurrents of the conversation like a pleasing background noise. Neal had lost himself in hypnotic and elaborated reasoning, attempting to explain why it was absolutely necessary to know the names and positions of the stars and how it would be easy to learn all that by checking out a stellar atlas during his downtime, but Jack had come away with a single clear point: that he would check it out during his downtime.

Jack never worried much about understanding where Neal was headed with the things he said, even if in his frenzy he seemed like he was desperately seeking to get to some specific point. Jack didn’t worry—he was convinced that not even Neal knew where he wanted to end up. The wonderful thing about Neal wasn’t where he wanted to end up, but how his hammering away at words got in the way of his thoughts. Obviously Neal thought about this in a completely different way. Neal was convinced he had specific things to say, but that the very nature of the things hindered their illumination and that this fact should be as clear to everyone else as it was to him. Everyone else, however, refused to follow him because they didn’t understand; only Jack and women—albeit for different reasons—followed him, thinking that deep down there wasn’t anything to understand at all. The consequence being that Neal and Jack—and women—wound up not understanding each other. But the difference between Jack’s incomprehension and women’s incomprehension was that, for better or worse, Neal kept being Jack’s friend even if Jack refused to understand. The women, on the other hand, were left to their lot because they would never have understood anyway.

Then there was another distinction tied to Neal’s usual way of speaking and this was that Neal’s way constituted the difference between Jack and Neal in their dealings with women. This difference was in its turn another reason why Jack found it unnecessary to understand where Neal was going with the things he said. If Neal saw one of those blondes you happen upon once in a lifetime, he’d stare right at her and ask her to point him to the nearest post office. “It works every time,” Neal said. “The post office is not only absolutely trustworthy in the public sphere, but it is also the symbol of noble and yearning communication that instinctively implies loving correspondence and puts the girl in the most trusting and therefore accommodating disposition.” Works every time and, as a matter of fact, it did. Or rather, it worked for him. Jack repeatedly vowed to try and use the post office line, but potential opportunities presented themselves in the wrong places, like at the movie theater ticket window, or times when the post office was mercilessly closed.

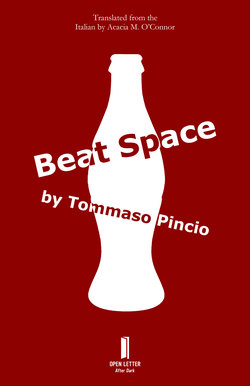

“Don’t get hung up on the object because the object is chimerical,” Neal explained. “The post office is simply love . . . what matters is the way you hold the rod.” Obviously Neal had never been fishing in his life. Jack knew this, which is why he let Neal say his piece and, without listening to him, thought about how in the end everyone had to flirt however felt most natural and he felt most at ease using Space™. Attempting to conquer—although “conquer” didn’t quite capture how he felt about it—attempting to conquer a girl by relying on the industrial chance that a comet that might dart across a bottle of Coca-Cola Space™, put him at peace with the system. If just one of those bottles created the conditions in which a young misfit might pass a night of tenderness, sinking into a pair of doe eyes that seemed to submit to the inflexible insensitivity of the world, then it could also be said that there was some possibility of redemption in the market economy. It was the sort of dream that consumed him and somehow drew him with irresistible nostalgia toward a world he wasn’t fully part of—the neon signs of all shapes, the transparent reflections of windows, the chain stores and their uniformed shopgirls, the jingle of cash registers, the rush of the air conditioning, the smooth colored surfaces, the frozen foods and diet soft drinks, the escalators rising up and up toward departments on top floors.