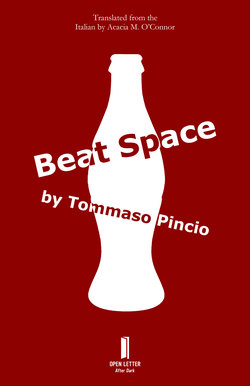

Читать книгу Beat Space - Tommaso Pincio - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3.

Day 1 in the Void passed by like any other day. He mentally composed a haiku and then contemplated the blackness of the universe, letting the day elapse in his omnipotence.

Star-words, words of stars

You stars are speaking to me

I don’t understand

At the start of Day 2, Jack Kerouac thought he was really earning his pay. He had done precisely what they had asked of him—nothing, in other words. He felt proud and, in some part of his being, something close to self-satisfied. It made him feel foolish. Here I am, in the face of the great Void and I’m worrying about being an honest worker! he reproached himself. Why can’t I be empty and indifferent like Space? Why do things affect me like this?

The people who had hired him as an Orbital Inspector sincerely despised him. That’s if they felt anything toward him at all, or even remembered his name. Arthur Miller and the others at Coca-Cola Enterprise Inc. considered him to be among the dregs of society, an irrecoverable misfit, a member of that pathetic element of society destined to run from nothing his entire life.

“It’s not true—I’m not running from nothing. I’m running from the direction of traffic,” he had explained to Arthur Miller the day before he embarked on his nine weeks as Orbital Inspector.

“Course. You say 'change course,'” Miller had said to him. “Christ Kerouac, you’re leaving for Space and you talk like a cabbie from New York.”

And he said: “We should think of Space as a huge street. Courses are an illusion; there’s just one big street and we have to change the direction of traffic.”

“Whatever, change the direction of your traffic all you like, but try to understand something about this job. I’m not the type of guy who likes screw ups, I love boredom and hate surprises, so no unexpected fuckery. Have I made myself clear?”

“I think so. I have nothing against the job, I was talking about life in general. Changing the direction of traffic is a mental thing. I mean, take you for example: you put in your eight hours in this fantastic office and then you go home and maybe even to your beautiful house and beautiful wife. You enjoy your house and eat, and screw your wife, watch a little TV, go to sleep, and the next day you’re back in this fantastic piece-of-shit office. It’s like a circle, but it’s also an illusion. It seems like it goes round and round and you know what’s happening instead?”

Arthur Miller was staring at his documents and seemed unmoved to respond. Kerouac insisted, trying to zero in on Miller’s lowered gaze. “You know what happens?”

“I don’t give a damn about what happens, I told you: no screw ups. That’s the only thing I care about.”

But by this point, Kerouac had gotten engulfed in the fervor of his train of thought. “What happens is you keep on moving in a straight line, you’ve covered another nice stretch of road and before you know it you discover you’re old, sick, alone, two steps from death and . . . ”

“That’s enough!” Miller interrupted him peremptorily. “Just shut up for two seconds.”

Kerouac hushed and began to watch Miller, who continued to examine his documents. Then, losing track of time, he let himself be hypnotized by the contents of a giant prototype of Coca-Cola Space™ that sat in all its imposing beauty on Miller’s desk. For the launch of this new version the company had revived the original hobble-skirt model, the goddess-like Mae West design of 1914. The color of the soft drink had been tweaked just enough to give it a cosmos-black shade. The introduction of a derivative of flourine into the recipe was the real discovery—it reacted with the carbonic acid to make the bubbles glow with actual light. In that moment, the bubbles in the prototype were swimming lazily and aimlessly, like a peaceful summer night sky, but if you were to shake the bottle you might see one of the bubbles hurtling toward the bottle cap, leaving a twinkling trail in its wake. People had gotten into the habit of shaking Coca-Cola Space™ before drinking it in the hopes that a bubble-comet would appear so they could make a wish. Kerouac was in the habit of doing this. Actually, he used Space™ to pick up girls. His technique was to strike up a conversation in this way: “Listen, Stella, you are the most fantastic creature in the entire known universe and that’s why I bought a Space™. I thought you could give it a good shake for me and if a bubble-comet shows up, well, you might just decide to change my life.” Bottles with a bubble-comet were roughly one in a thousand and girls were well-aware of this fact. Still, they played along, they gave it a shake and then ended it there with a “Sorry.” Once, though, he happened upon a girl with real personality. Tall, blonde, volumetrically smooth and seductively humoral. He led off with the usual business of the known universe, Space™ and all the rest. She looked at him impassively, then she grabbed the Space™ and smacked it over his head.

Additionally, something particularly special was possible with the new type of Coke. They said that for every one billion eight million bottles—that is to say equivalent to the speed of light in kilometers per hour—there would be one in which the outline of a rocket appeared. The fortunate few who were able to get their hands on a Space™ with a rocket would make a wish that Coca-Cola Enterprise Inc. then sought to grant. They also said that the only lucky person so far had been a general named Eisenhower, who—again, according to what they said—had asked to become president of the United States and had his wish granted.

Kerouac thought it a stupid wish. In fact it wasn’t even a wish, it was a contract. Yes, a contract.

“Hey, Arthur, is it true what they say?” Kerouac asked him, his eyes still fixed on the Space™ prototype.

“What?” Miller asked.

“The thing about Eisenhower, I mean. Did he really ask to be made president?”

“What do you mean ask?” Miller repeated without looking up from his work.

“What do you mean what do I mean? A rocket showed up in his bottle and you guys made him president. Is it true or not?”

“You’re kidding me, Kerouac. Do you actually buy this bullshit? Only children shake up Space™ to see if they get a rocket.”

“I do it.”

“Do whatever, I just don’t want any screw ups.”

“Yes, I get it, ok. But you didn’t answer me.”

“That’s because I don’t have an answer for you. I oversee the management of our space program, if you’re interested in promotions they deal with that stuff in Atlanta.”

“What the hell, Arthur. You’re one of the guys calling the shots in this show so don’t try and tell me you don’t know how things work. I know you know. Why would you say something like that to me? Am I or am I not also part of the family now?”

Miller had lifted his head from his paperwork and stared at him for a hierarchically calibrated number of seconds and then said: “You’re not part of shit, Kerouac. You’re a nobody who’s about to be sent to circle this planet and do the most inane job in the universe and I have serious doubts about whether you’re even capable of doing that without causing me a shit-ton of problems. Let me be clear, Kerouac. You and all the other idiots who’ll come after you matter less than a bottle cap in this family.”

“You’re pathetic, Arthur. You and your direction of traffic are pathetic.”

“Less than a single bottle cap,” Miller repeated, looking him in the eyes with a glassy expression while he stretched out his hand, handing him forms to sign.

“This is my contract?”

“You don’t need a contract for a job like this. It’s a release.”

“A release for what?”

“That, should something happen to you, you relieve us of any legal liability and of the obligation to keep your loved ones and relatives informed—if you have them, that is.”

“It doesn’t seem like a very honest contract to me.”

“Well it’s not a contract, just a release. There’s no negotiating, if you want the job, sign. No signature, no job.”

Kerouac looked over the forms for a few moments without really reading them. “And what could happen to me?”

“No signature, no job.” Clearly, it was Miller’s belief that repetition imbued his words with persuasive sense of authoritative unavoidability.

“You’re sure you’re not conning me?”

“See what goes through your head thanks to that unhinged life of yours? There might be con men in the circles of parasites you hang around with, but here there are rules. This is the very heart of the system, Kerouac.”

Those words had stolen Jack’s desire to open his mouth, and yet almost by inertia the anxiety of negotiation set in. “Bullshit about the rules aside, I’ll sign. But you better tell me the truth about the bubbles in Space™.”

“We’ll talk about it when you get back.”

“Done. But when I get back you’re telling me everything. No cons.”

“You just worry yourself about getting back.”

The entirety of Day 3, Jack did nothing but ask himself whether signing that release had been a good idea after all.