Читать книгу Tomoko Fuse's Origami Art - Tomoko Fuse - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеORIGAMI AS ART

Among traditional handmade items used on a daily basis in Japan is the furoshiki, a bundle for holding and transporting goods, and the kimono, the country’s quintessential clothing item. In both, the most conspicuous formal quality is two-dimensionality.

When fulfilling the task of wrapping contents (that is, when used to transport a load), the furoshiki transforms itself from a flat piece of cloth into a three-dimensional object. So too does the kimono, which, when performing its function as a piece of clothing for covering the body, acquires volume and depth. Nonetheless, both the furoshiki and the kimono start out as flat, two-dimensional objects. The first is nothing but a square piece of cloth; the second, once folded, turns into thin layers of fabric (unlike Western garments which remain three-dimensional even when folded). In both cases, we confront something two-dimensional that becomes volumetric. Here, therefore, is the Japanese sense of form, one that is based on the concept of flat surfaces.

In the realm of contemporary art, Takashi Murakami has gained attention on the international art scene by working on the concept of Superflat, a term that captures the exaggeration of two-dimensionality which characterizes Japanese expression as a whole, not only manga and anime, but even the country’s ancient art, particularly ukiyoe.

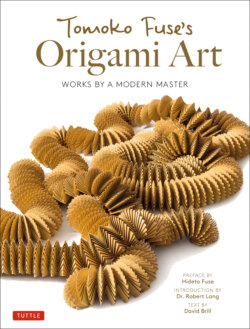

The work of the origami artist Tomoko Fuse, in which form arises from the folding of a two-dimensional sheet of paper, is likewise based on a flat surface. In origami, a two-dimensional square is manipulated to obtain another kind of form that develops differently in space, but the starting point remains very similar to that of furoshiki. It is precisely from this two-dimensional square that—as if by magic—the sculpted form is born and reveals the art of Tomoko Fuse. Perhaps it is by chance that kami, the Japanese word for “paper,” also means “god.” What is certain, however, is that in the hands of Tomoko Fuse, paper acquires a sublime beauty that brings it closer to the divine.

But let us see how this paper universe of Tomoko Fuse’s work is configured. The photographs and explanatory illustrations that unfold in the pages of this book, offer a comprehensive essay broken down into five chapters that bring together “nodes,” “tessellations,” “endless folds,” “multiple folds,” and, finally, works illuminated from within.

Like art as a whole, so too origami can be figurative or abstract. Much origami does tend towards figurative subjects such as flowers, birds, and insects. But even a quick flip through the pages of this collection will reveal that the works here are nearly all abstract. One could say, in effect, that works such as these make us ask whether origami is an abstract art. Therefore, let us try to frame the work of Tomoko Fuse in the context of contemporary art, particularly that of the twentieth century.

MODELING WITH SWALLOW 45

CIRCULAR STUMP

Height x Diameter

9 x 19.3 inches (230 x 490 mm)

Take, for example, the “nodes” in Chapter 1. The sight of them makes my mind jump to the paintings of Piet Mondrian, to the intersections of their horizontal and vertical lines. Taking figurative art as his starting point, the painter developed his style through successive simplification, submitting images of trees and houses to a process of abstraction in order to extract from them grids constructed of perpendicular lines. Next, he extended the process of simplification and abstraction to color, which led him to retain—in addition to black and gray—only red, blue, and yellow. Tomoko Fuse’s “nodes” are structures fabricated out of thin strips of paper that are inserted into an intersection of lines. What makes them different from the works of Mondrian is the angle of intersection, which does not necessarily have to be 90 degrees, and the point of departure, which does not consist of simplifying and abstracting figurative images but working directly with geometrical and mathematical concepts.

The next series, which falls under the title “flat folds” recalls Picasso and Braque’s Cubism. While painting generally strives to create the impression of depth on a flat surface, that is, three-dimensions in two-dimensions, Picasso and the Cubists compose figures by combining multiple images (flat surfaces) from different viewpoints so as to create solid figures, or “cubes.” Of course, flat folds do not generate similar “images arising from multiple viewpoints,” but they do reveal an urge for three-dimensionality—much like that of Cubism—in which the flat surface of the paper springs into a sort of high relief.

The “endless folds” of Chapter 3 and the “multiple folds” of Chapter 4 remind me (perhaps somewhat audaciously) of the work of Andy Warhol, of his multiple soup cans or movie stars that, reflecting on mass production and consumption in capitalist society, showcase the repetition of a subject and turn this “act of repetition” into an artistic gesture. This kind of Warholian aesthetic is not alien to certain of Tomoko Fuse’s figures, in which an element may repeat itself and multiply indefinitely. Yet, what is also present in them is the mathematical and philosophical concept of “infinity.” Infinity signifies infinite growth, or something increasing to infinity, hence the infinitely large, as well as infinite diminution, hence the infinitely small. Both are present in Tomoko Fuse’s universe: the infinitely large of endlessly repeating folds, and the infinitely small of an element divided in half, and then in half again. In some works, the infinitely small assumes amazing shapes, inexplicable even in mathematical terms, as when a long, thin triangle, through a series of folds, finally approaches the form of an equilateral triangle.

TORNADO

Height x Diameter 9.4 x 18.9 inches (240 x 480 mm)

Now, as a three-dimensional object, origami is constituted of a combination of flat surfaces, as is a Cubist painting, as already noted. And, as is the case in Cubist painting, each of these various surfaces are presented from a different angle. In the presence of a light source, some surfaces will cast shadows, while others (if the origami is made from white paper) will brightly glow. Such play of light and shadow is magical.

The “luminous” series of Chapter 5 does not simply respond to an external light source, but rather introduces light into its solid forms, illuminating them from within. In this way, origami becomes a light instrument, a lamp. If in certain respects the work of Tomoko Fuse recalls contemporary and abstract art, in other respects it lends itself to novel applications in the field of design.

Tomoko has been creating these works in her home in the mountains of Nagano for thirty years. In order to gather material for this essay, I visited her home-studio. (By coincidence we bear the same surname but we are not, in fact, related.) Tomoko lives with her husband, the woodblock printmaker Taro Toriumi, and a cat. On the shelves in her studio were sheets of all kinds of paper (were she a painter, these would have been paint tubes) and hundreds of tiny works, little models and experiments tightly arranged in beautiful order in a series of boxes. Faced with this display of creativity, I asked myself whether I was in an artist’s studio or in the laboratory of a scientist (particularly one studying geometry).

Is Tomoko Fuse’s work ultimately art or science? According to her, it is science (mathematics) for artists and art for scientists. Members of each category would tend to regard it as a world other than their own. This would be correct if origami were in truth a genre unto itself, different from both art and science, but the truth is that it falls within the sphere of both art and science.

In this age of ours, which is advancing towards ever greater specialization and reduction in general skills, the transcendence of borders, the ability to connect different worlds is extremely valuable. Origami, besides simply being a set of gestures for folding paper, is also a significant activity that is capable of uniting art and science within itself.

Hideto Fuse

GARDEN IN SPRING

16.7 x 68.5 inches (425 x 1740 mm)

PAPER Washi/Kashiki, Kochi/Hand dyeing