Читать книгу Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead - Tom Stoppard - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPREFACE

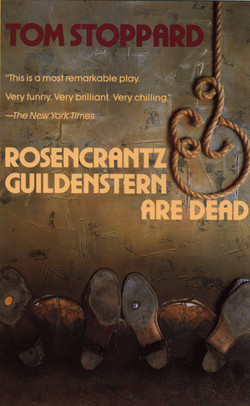

When Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead opened in April 1967— performed by the National Theatre at the Old Vic—a play about Hamlet’s ‘excellent good friends’ had been on my mind for three years or so. I had spent part of the summer of 1964 in Berlin at a ‘literary colloquium’ for promising young playwrights, and my graduation piece was a sketch about Rosencrantz and Guildenstern finding themselves in England. I developed this backwards into a full-length play in which our heroes are discovered on their way to Elsinore, and it was accepted by the Royal Shakespeare Company. But the planned production fell by the wayside, and the RSC passed the script to the incumbent director of the Oxford Playhouse, Frank Hauser, who in turn passed it on to an undergraduate company, the Oxford Theatre Group. The OTG performed the play on the Edinburgh Festival fringe in August 1966. A review by Ronald Bryden in the Observer was such that when I returned to London it was to find a telegram from Kenneth Tynan, the literary manager of the National Theatre, asking to read the play.

In 1966 the administration of the National Theatre occupied a long wooden hut with a rehearsal room at one end, Laurence Olivier’s office at the other, and somewhere between the two a tiny room hardly big enough to contain Tynan’s desk. A hatch in the wall communicated with his secretary. Ten years earlier, Tynan, as the Observer’s theatre critic, had changed the landscape with his review of Look Back in Anger. Six years earlier, I had written my first play. As far as I was concerned, to be sitting in Tynan’s visitor’s chair was to have arrived on Olympus. He had an attractive stammer, and to my consternation I heard myself stammering back at him. I remember nothing else of our meeting except that his primrose yellow polo-necked shirt—a short-lived fashion—gave him much pleasure.

At the beginning of March—by which time I had at Olivier’s prompting added to my play— ‘R and G’, as I called it, was in rehearsal. One day, Olivier popped in to watch for a while. He offered a suggestion, and as he left the room he turned and said, ‘Just the odd pearl.’ In due course we occupied the Old Vic stage for our technical rehearsals, followed by the dress rehearsal, and the next night we opened. Previews, an American innovation, were as yet unknown in England, so the terror of the opening night was on a scale I was not to experience again.

Thus it was that I and my wife sat watching the curtain go up on 11 April, and not many minutes later an elderly man in evening dress sitting in front of us sighed heavily and muttered, ‘I do wish they’d get on.’ It was largely because of him, I think, that we never emerged from the pub at the first interval and were pleasantly surprised by the exulting actors when the play was over.

For fifty years now, on being asked what Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead is about, I have stood pat on ‘It’s about two courtiers at Elsinore.’ I wasn’t insensitive to more suggestive possibilities but I took the view that every subjective response had its own validity: no interpretations endorsed, none denied. The one I liked best, however, was by a Fleet Street journalist who was at the first night. ‘I get it,’ he said, ‘it’s two reporters on a story that doesn’t stand up.’

T.S.