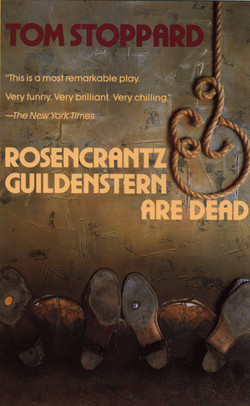

Читать книгу Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead - Tom Stoppard - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеACT ONE

Two Elizabethans passing the time in a place without any visible character.

They are well dressed—hats, cloaks, sticks and all.

Each of them has a large leather money bag.

GUILDENSTERN’s bag is nearly empty.

ROSENCRANTZ’s bag is nearly full.

The reason being: they are betting on the toss of a coin, in the following manner: Guildenstern (hereafter “GUIL”) takes a coin out of his bag, spins it, letting it fall. Rosencrantz (hereafter “ROS”) studies it, announces it as “heads” (as it happens) and puts it into his own bag. Then they repeat the process. They have apparently been doing this for some time.

The run of “heads’’ is impossible, yet Ros betrays no surprise at all—he feels none. However, he is nice enough to feel a little embarrassed at taking so much money off his friend. Let that be his character note.

Guil is well alive to the oddity of it. He is not worried about the money, but he is worried by the implications; aware but not going to panic about it—his character note.

Guil sits. Ros stands (he does the moving, retrieving coins).

Guil spins. Ros studies coin.

ROS Heads.

He picks it up and puts it in his bag. The process is repeated.

Heads.

Again.

Heads.

Again.

Heads.

Again.

Heads.

GUIL (flipping a coin) There is an art to the building up of suspense.

ROS Heads.

GUIL (flipping another) Though it can be done by luck alone.

ROS Heads.

GUIL If that’s the word I’m after.

ROS (raises his head at Guil) Seventy-six—love.

Guil gets up but has nowhere to go. He spins another coin over his shoulder without looking at it, his attention being directed at his environment or lack of it.

Heads.

GUIL A weaker man might be moved to re-examine his faith, if in nothing else at least in the law of probability. (He slips a coin over his shoulder as he goes to look upstage.)

ROS Heads.

Guil, examining the confines of the stage, flips over two more coins as he does so, one by one of course. Ros announces each of them as “heads.”

GUIL (musing) The law of probability, it has been oddly asserted, is something to do with the proposition that if six monkeys (he has surprised himself) . . . if six monkeys were . . .

ROS Game?

GUIL Were they?

ROS Are you?

GUIL (understanding) Game. (Flips a coin.) The law of averages, if I have got this right, means that if six monkeys were thrown up in the air for long enough they would land on their tails about as often as they would land on their—

ROS Heads. (He picks up the coin.)

GUIL Which even at first glance does not strike one as a particularly rewarding speculation, in either sense, even without the monkeys. I mean you wouldn’t bet on it. I mean I would, but you wouldn’t . . . (As he flips a coin.)

ROS Heads.

GUIL Would you? (Flips a coin.)

ROS Heads.

Repeat.

Heads. (He looks up at Guil—embarrassed laugh.) Getting a bit of a bore, isn’t it?

GUIL (coldly) A bore?

ROS Well . . .

GUIL What about the suspense?

ROS (innocently) What suspense?

Small pause.

GUIL It must be the law of diminishing returns. . . . I feel the spell about to be broken. (Energizing himself somewhat. He takes out a coin, spins it high, catches it, turns it over on to the back of his other hand, studies the coin—and tosses it to Ros. His energy deflates and he sits.)

Well, it was an even chance . . . if my calculations are correct.

ROS Eighty-five in a row—beaten the record!

GUIL Don’t be absurd.

ROS Easily!

GUIL (angry) Is that it, then? Is that all?

ROS What?

GUIL A new record? Is that as far as you are prepared to go?

ROS Well . . .

GUIL No questions? Not even a pause?

ROS You spun them yourself.

GUIL Not a flicker of doubt?

ROS (aggrieved, aggressive) Well, I won—didn’t I?

GUIL (approaches him—quieter) And if you’d lost? If they’d come down against you, eighty-five times, one after another, just like that?

ROS (dumbly) Eighty-five in a row? Tails?

GUIL Yes! What would you think?

ROS (doubtfully) Well. . . . (Jocularly.) Well, I’d have a good look at your coins for a start!

GUIL (retiring) I’m relieved. At least we can still count on self-interest as a predictable factor. . . . I suppose it’s the last to go. Your capacity for trust made me wonder if perhaps . . . you, alone . . . (He turns on him suddenly, reaches out a hand.) Touch.

Ros clasps his hand. Guil pulls him up to him.

GUIL (more intensely) We have been spinning coins together since—(He releases him almost as violently.) This is not the first time we have spun coins!

ROS Oh no—we’ve been spinning coins for as long as I remember.

GUIL How long is that?

ROS I forget. Mind you—eighty-five times!

GUIL Yes?

ROS It’ll take some beating, I imagine.

GUIL Is that what you imagine? Is that it? No fear?

ROS Fear?

GUIL (in fury—flings a coin on the ground) Fear! The crack that might flood your brain with light!

ROS Heads. . . . (He puts it in his bag.)

Guil sits despondently. He takes a coin, spins it, lets it fall between his feet. He looks at it, picks it up, throws it to Ros, who puts it in his bag.

Guil takes another coin, spins it, catches it, turns it over on to his other hand, looks at it, and throws it to Ros, who puts it in his bag.

Guil takes a third coin, spins it, catches it in his right hand, turns it over onto his left wrist, lobs it in the air, catches it with his left hand, raises his left leg, throws the coin up under it, catches it and turns it over on the top of his head, where it sits. Ros comes, looks at it, puts it in his bag.

ROS I’m afraid—

GUIL So am I.

ROS I’m afraid it isn’t your day.

GUIL I’m afraid it is.

Small pause.

ROS Eighty-nine.

GUIL It must be indicative of something, besides the redistribution of wealth. (He muses.) List of possible explanations. One: I’m willing it. Inside where nothing shows, I am the essence of a man spinning double-headed coins, and betting against himself in private atonement for an unremembered past. (He spins a coin at Ros.)

ROS Heads.

GUIL Two: time has stopped dead, and the single experience of one coin being spun once has been repeated ninety times. . . . (He flips a coin, looks at it, tosses it to Ros.) On the whole, doubtful. Three: divine intervention, that is to say, a good turn from above concerning him, cf. children of Israel, or retribution from above concerning me, cf. Lot’s wife. Four: a spectacular vindication of the principle that each individual coin spun individually (he spins one) is as likely to come down heads as tails and therefore should cause no surprise each individual time it does. (It does. He tosses it to Ros.)

ROS I’ve never known anything like it!

GUIL And a syllogism: One, he has never known anything like it. Two, he has never known anything to write home about. Three, it is nothing to write home about. . . . Home . . . What’s the first thing you remember?

ROS Oh, let’s see . . . The first thing that comes into my head, you mean?

GUIL No—the first thing you remember.

ROS Ah. (Pause.) No, it’s no good, it’s gone. It was a long time ago.

GUIL (patient but edged) You don’t get my meaning. What is the first thing after all the things you’ve forgotten?

ROS Oh I see. (Pause.) I’ve forgotten the question.

Guil leaps up and paces.

GUIL Are you happy?

ROS What?

GUIL Content? At ease?

ROS I suppose so.

GUIL What are you going to do now?

ROS I don’t know. What do you want to do?

GUIL I have no desires. None. (He stops pacing dead.) There was a messenger . . . that’s right. We were sent for. (He wheels at Ros and raps out:) Syllogism the second: One, probability is a factor which operates within natural forces. Two, probability is not operating as a factor. Three, we are now within un-, sub- or supernatural forces. Discuss. (Ros is suitably startled. Acidly.) Not too heatedly.

ROS I’m sorry I—What’s the matter with you?

GUIL The scientific approach to the examination of phenomena is a defence against the pure emotion of fear. Keep tight hold and continue while there’s time. Now—counter to the previous syllogism: tricky one, follow me carefully, it may prove a comfort. If we postulate, and we just have, that within un-, sub- or supernatural forces the probability is that the law of probability will not operate as a factor, then we must accept that the probability of the first part will not operate as a factor, in which case the law of probability will operate as a factor within un-, sub- or supernatural forces. And since it obviously hasn’t been doing so, we can take it that we are not held within un-, sub- or supernatural forces after all; in all probability, that is. Which is a great relief to me personally. (Small pause.) Which is all very well, except that—(He continues with tight hysteria, under control.) We have been spinning coins together since I don’t know when, and in all that time (if it is all that time) I don’t suppose either of us was more than a couple of gold pieces up or down. I hope that doesn’t sound surprising because its very unsurprisingness is something I am trying to keep hold of. The equanimity of your average tosser of coins depends upon a law, or rather a tendency, or let us say a probability, or at any rate a mathematically calculable chance, which ensures that he will not upset himself by losing too much nor upset his opponent by winning too often. This made for a kind of harmony and a kind of confidence. It related the fortuitous and the ordained into a reassuring union which we recognized as nature. The sun came up about as often as it went down, in the long run, and a coin showed heads about as often as it showed tails. Then a messenger arrived. We had been sent for. Nothing else happened. Ninety-two coins spun consecutively have come down heads ninety-two consecutive times . . . and for the last three minutes on the wind of a windless day I have heard the sound of drums and flute. . . .

ROS (cutting his fingernails) Another curious scientific phenomenon is the fact that the fingernails grow after death, as does the beard.

GUIL What?

ROS (loud) Beard!

GUIL But you’re not dead.

ROS (irritated) I didn’t say they started to grow after death! (Pause, calmer.) The fingernails also grow before birth, though not the beard.

GUIL What?

ROS (shouts) Beard! What’s the matter with you? (Reflectively.) The toenails, on the other hand, never grow at all.

GUIL (bemused) The toenails never grow at all?

ROS Do they? It’s a funny thing—I cut my fingernails all the time, and every time I think to cut them, they need cutting. Now, for instance. And yet, I never, to the best of my knowledge, cut my toenails. They ought to be curled under my feet by now, but it doesn’t happen. I never think about them. Perhaps I cut them absent-mindedly, when I’m thinking of something else.

GUIL (tensed up by this rambling) Do you remember the first thing that happened today?

ROS (promptly) I woke up, I suppose. (Triggered.) Oh—I’ve got it now—that man, a foreigner, he woke us up—

GUIL A messenger. (He relaxes, sits.)

ROS That’s it—pale sky before dawn, a man standing on his saddle to bang on the shutters—shouts—What’s all the row about?! Clear off!—But then he called our names. You remember that—this man woke us up.

GUIL Yes.

ROS We were sent for.

GUIL Yes.

ROS That’s why we’re here. (He looks round, seems doubtful, then the explanation.) Travelling.

GUIL Yes.

ROS (dramatically) It was urgent—a matter of extreme urgency, a royal summons, his very words: official business and no questions asked—lights in the stable-yard, saddle up and off headlong and hotfoot across the land, our guides outstripped in breakneck pursuit of our duty! Fearful lest we come too late!!

Small pause.

GUIL Too late for what?

ROS How do I know? We haven’t got there yet.

GUIL Then what are we doing here, I ask myself.

ROS You might well ask.

GUIL We better get on.

ROS You might well think.

GUIL We better get on.

ROS (actively) Right! (Pause.) On where?

GUIL Forward.

ROS (forward to footlights) Ah. (Hesitates.) Which way do we—(He turns round.) Which way did we—?

GUIL Practically starting from scratch . . . An awakening, a man standing on his saddle to bang on the shutters, our names shouted in a certain dawn, a message, a summons . . . A new record for heads and tails. We have not been . . . picked out . . . simply to be abandoned . . . set loose to find our own way. . . . We are entitled to some direction. . . . I would have thought.

ROS (alert, listening) I say—! I say—

GUIL Yes?

ROS I can hear—I thought I heard—music.

Guil raises himself.

GUIL Yes?

ROS Like a band. (He looks around, laughs embarrassedly, expiating himself.) It sounded like—a band. Drums.

GUIL Yes.

ROS (relaxes) It couldn’t have been real.

GUIL “The colours red, blue and green are real. The colour yellow is a mystical experience shared by everybody”—demolish.

ROS (at edge of stage) It must have been thunder. Like drums . . .

By the end of the next speech, the band is faintly audible.

GUIL A man breaking his journey between one place and another at a third place of no name, character, population or significance, sees a unicorn cross his path and disappear. That in itself is startling, but there are precedents for mystical encounters of various kinds, or to be less extreme, a choice of persuasions to put it down to fancy; until—“My God,” says a second man, “I must be dreaming, I thought I saw a unicorn.” At which point, a dimension is added that makes the experience as alarming as it will ever be. A third witness, you understand, adds no further dimension but only spreads it thinner, and a fourth thinner still, and the more witnesses there are the thinner it gets and the more reasonable it becomes until it is as thin as reality, the name we give to the common experience . . . “Look, look!” recites the crowd. “A horse with an arrow in its forehead! It must have been mistaken for a deer.”

ROS (eagerly) I knew all along it was a band.

GUIL (tiredly) He knew all along it was a band.

ROS Here they come!

GUIL (at the last moment before they enter—wistfully) I’m sorry it wasn’t a unicorn. It would have been nice to have unicorns.

The TRAGEDIANS are six in number, including a small boy (ALFRED). Two pull and push a cart piled with props and belongings. There is also a DRUMMER, a HORN-PLAYER and a FLAUTIST. The SPOKESMAN (“the PLAYER”) has no instrument. He brings up the rear and is the first to notice them.

PLAYER Halt!

The group turns and halts.

(Joyously.) An audience!

Ros and Guil half rise.

Don’t move!

They sink back. He regards them fondly.

Perfect! A lucky thing we came along.

ROS For us?

PLAYER Let us hope so. But to meet two gentlemen on the road—we would not hope to meet them off it.

ROS No?

PLAYER Well met, in fact, and just in time.

ROS Why’s that?

PLAYER Why, we grow rusty and you catch us at the very point of decadence—by this time tomorrow we might have forgotten everything we ever knew. That’s a thought, isn’t it? (He laughs generously.) We’d be back where we started—improvising.

ROS Tumblers, are you?

PLAYER We can give you a tumble if that’s your taste, and times being what they are. . . . Otherwise, for a jingle of coin we can do you a selection of gory romances, full of fine cadence and corpses, pirated from the Italian; and it doesn’t take much to make a jingle—even a single coin has music in it.

They all flourish and bow, raggedly.

Tragedians, at your command.

Ros and Guil have got to their feet.

ROS My name is Guildenstern, and this is Rosencrantz.

Guil confers briefly with him.

(Without embarrassment.) I’m sorry—his name’s Guildenstern, and I’m Rosencrantz.

PLAYER A pleasure. We’ve played to bigger, of course, but quality counts for something. I recognized you at once—

ROS And who are we?

PLAYER —as fellow artists.

ROS I thought we were gentlemen.

PLAYER For some of us it is performance, for others, patronage. They are two sides of the same coin, or, let us say, being as there are so many of us, the same side of two coins. (Bows again.) Don’t clap too loudly—it’s a very old world.

ROS What is your line?

PLAYER Tragedy, sir. Deaths and disclosures, universal and particular, denouements both unexpected and inexorable, transvestite melodrama on all levels including the suggestive. We transport you into a world of intrigue and illusion . . . clowns, if you like, murderers—we can do you ghosts and battles, on the skirmish level, heroes, villains, tormented lovers—set pieces in the poetic vein; we can do you rapiers or rape or both, by all means, faithless wives and ravished virgins—flagrante delicto at a price, but that comes under realism for which there are special terms. Getting warm, am I?

ROS (doubtfully) Well, I don’t know. . . .

PLAYER It costs little to watch, and little more if you happen to get caught up in the action, if that’s your taste and times being what they are.

ROS What are they?

PLAYER Indifferent.

ROS Bad?

PLAYER Wicked. Now what precisely is your pleasure? (He turns to the Tragedians.) Gentlemen, disport yourselves.

The Tragedians shuffle into some kind of line.

There! See anything you like?

ROS (doubtful, innocent) What do they do?

PLAYER Let your imagination run riot. They are beyond surprise.

ROS And how much?

PLAYER To take part?

ROS To watch.

PLAYER Watch what?

ROS A private performance.

PLAYER How private?

ROS Well, there are only two of us. Is that enough?

PLAYER For an audience, disappointing. For voyeurs, about average.

ROS What’s the difference?

PLAYER Ten guilders.

ROS (horrified) Ten guilders!

PLAYER I mean eight.

ROS Together?

PLAYER Each. I don’t think you understand—

ROS What are you saying?

PLAYER What am I saying—seven.

ROS Where have you been?

PLAYER Roundabout. A nest of children carries the custom of the town. Juvenile companies, they are the fashion. But they cannot match our repertoire . . . we’ll stoop to anything if that’s your bent. . . .

He regards Ros meaningfully but Ros returns the stare blankly.

ROS They’ll grow up.

PLAYER (giving up) There’s one born every minute. (To Tragedians:) On-ward!

The Tragedians start to resume their burdens and their journey. Guil stirs himself at last.

GUIL Where are you going?

PLAYER Ha-alt!

They halt and turn.

Home, sir.

GUIL Where from?

PLAYER Home. We’re travelling people. We take our chances where we find them.

GUIL It was chance, then?

PLAYER Chance?

GUIL You found us.

PLAYER Oh yes.

GUIL You were looking?

PLAYER Oh no.

GUIL Chance, then.

PLAYER Or fate.

GUIL Yours or ours?

PLAYER It could hardly be one without the other.

GUIL Fate, then.

PLAYER Oh yes. We have no control. Tonight we play to the court. Or the night after. Or to the tavern. Or not.

GUIL Perhaps I can use my influence.

PLAYER At the tavern?

GUIL At the court. I would say I have some influence.

PLAYER Would you say so?

GUIL I have influence yet.

PLAYER Yet what?

Guil seizes the Player violently.

GUIL I have influence!

The Player does not resist. Guil loosens his hold.

(More calmly.) You said something—about getting caught up in the action—

PLAYER (gaily freeing himself) I did!—I did!—You’re quicker than your friend . . . (Confidingly.) Now for a handful of guilders I happen to have a private and uncut performance of The Rape of the Sabine Women—or rather woman, or rather Alfred—(Over his shoulder.) Get your skirt on, Alfred—

The Boy starts struggling into a female robe.

. . . and for eight you can participate.

Guil backs, Player follows.

. . . taking either part.

Guil backs.

. . . or both for ten.

Guil tries to turn away, Player holds his sleeve.

. . . with encores—

Guil smashes the Player across the face. The Player recoils. Guil stands trembling.

(Resigned and quiet). Get your skirt off, Alfred. . . .

Alfred struggles out of his half-on robe.

GUIL (shaking with rage and fright) It could have been—it didn’t have to be obscene. . . . It could have been—a bird out of season, dropping bright-feathered on my shoulder. . . . It could have been a tongueless dwarf standing by the road to point the way. . . . I was prepared. But it’s this, is it? No enigma, no dignity, nothing classical, portentous, only this—a comic pornographer and a rabble of prostitutes. . . .

PLAYER (acknowledging the description with a sweep of his hat, bowing; sadly) You should have caught us in better times. We were purists then. (Straightens up.) On-ward.

The Players make to leave.

ROS (his voice has changed: he has caught on) Excuse me!

PLAYER Ha-alt!

They halt.

A-al-l-fred!

Alfred resumes the struggle. The Player comes forward.

ROS You’re not—ah—exclusively players, then?

PLAYER We’re inclusively players, sir.

ROS So you give—exhibitions?

PLAYER Performances, sir.

ROS Yes, of course. There’s more money in that, is there?

PLAYER There’s more trade, sir.

ROS Times being what they are.

PLAYER Yes.

ROS Indifferent.

PLAYER Completely.

ROS You know I’d no idea—

PLAYER No—

ROS I mean, I’ve heard of—but I’ve never actually—

PLAYER No.