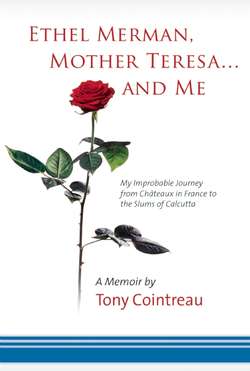

Читать книгу Ethel Merman, Mother Teresa...and Me - Tony Cointreau - Страница 18

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

MY ANNUS HORRIBILIS: AUTUMN 1949 – SUMMER 1950

ОглавлениеAutumn: Mr. Fuller

For as long as I could remember, two phrases besides “Mother only loves you when you’re perfect” were drummed into my head: Tata never tired of saying, “Bluebloods never give in,” and Mother—who was not comfortable with my childhood tears—was always reminding me, “Men don’t cry.” I think Tata said it tongue in cheek, but Mother was serious.

Mother’s admonishment was once again wasted on me when I dissolved in tears on my first day in the fourth grade at the Browning School for Boys in New York City. I was only eight, much younger and smaller than the other students in my class, which left me feeling vulnerable—as though I were coping with not just one aggressive older brother, but a whole roomful of them. I dreaded the year ahead.

Mr. Fuller, my new homeroom teacher, saw my tears and made a special effort to comfort me. He became my friend. Lucy saw him every day when she picked me up at school, and I could see that she had a crush on him, but he was my friend. From the beginning of the school year he gave me a special honor. I was proud when he asked me to stay with him in the afternoons after everyone else had gone, and put books and projects back into place.

It wasn’t long before he began to give me certain instructions that I knew I had to carry out precisely, and that had to remain our secret.

His desk was at the opposite end of the room from the door, facing sideways. First I had to stand next to his chair, with my back to the door, while he sat so deep into his desk that even I could not see what he was doing; only my back was visible if someone came to the door. I had to get as close to Mr. Fuller as possible while he reached for the opening in my pants. Then my mind went blank and time stood still. The last thing I could remember was looking down at the top of his grey hair from what seemed like a great distance. I never had to do anything—only stand there, perfectly still, while he did whatever he wanted with my body; I was the object.

When Lucy showed up to take me home, I always wondered how it had gotten so late. Hard as I tried, I could never comprehend where the time had gone. And Lucy, who had an extraordinary ability to ignore anything when it suited her, never questioned the situation when she came to pick me up after my solitary afternoons with Mr. Fuller.

On a sunny autumn day my school took a group of children to the country. Mr. Fuller said that he had a special surprise for me and I mustn’t tell anyone. He took me away from the others and told me to follow him into the woods and up a hill. There was a little stream running down the hill. It was only trickling water and I couldn’t understand why he made me walk up the middle of the stream instead of going along the side where it was dry.

By the time we reached the top, my shorts had gotten slightly wet, so he insisted that I take all my clothes off to dry. The sunlight filtering through the trees onto my naked body only highlighted my vulnerability. I was confused, not knowing what Mr. Fuller expected of me this time, and embarrassed by my nakedness. He positioned me in a certain way, and told me not to look back. None of his instructions made sense to me, but I obeyed him without question. Then I sensed his presence behind me. Endless time seemed to pass while I waited patiently in the pose he had indicated.

I hardly dared to breathe.

Then without warning he made his move, and I was too young and too innocent to protest or even to understand what he was doing, as he struggled to violate my young body in the worst possible way. I simply went numb.

One of my friends calling from the bottom of the hill finally brought me back to reality and Mr. Fuller into frenzied action. He insisted that I get my clothes back on, and nearly threw me down the hill. My little pal looked at me as I ran down the hill, buttoning my pants, and said, “You shouldn’t take off your pants with him. You don’t have to do that.” I was stunned by the notion that a child could have such boundaries.

By the time we reached the others, the pain had seared through to my consciousness. It nearly took my breath away. I hadn’t realized how badly Mr. Fuller had hurt me, and I didn’t understand the magnitude of what he had just done to me. The kids and teachers continued to play games while I lay on a tree trunk that had fallen down. I looked around for the only person I thought would understand and make it better, but Mr. Fuller wouldn’t come near me. And I never cried.

My mother, who had never met Mr. Fuller, answered the phone the next Saturday when he called to say that he was supposed to take some children to the country for the day. He told her that none of the other kids were able to make it, but he would be happy to take me anyway. Mother instinctively felt uncomfortable with the idea and made an excuse as to why I couldn’t go.

That night Mr. Fuller was arrested while sexually molesting another little boy. The story was in all the newspapers and Monday morning when I went to school, a new teacher had taken his place.

I never saw Mr. Fuller again, and even though my mother questioned me, I never gave him away. After all, I thought he was my friend. As far as I was concerned, that was my relationship with Mr. Fuller: he was my friend. It had nothing to do with sex; I didn’t understand sex at that age. It was uncomfortable, terrible—but he made it clear to me that it was my responsibility to be sure that no one knew what was happening while I was standing next to his desk; it was my responsibility that no one found out about our secret. It would be my fault if someone found out.

I did not tell anyone for forty-two years. I had no idea what price I was to pay for my silence.

Winter: The Hospital

A few weeks after Mr. Fuller had been arrested, I woke up feeling sick to my stomach and had to stay in bed all day, waiting for the doctor to come and see me. After a quick examination he told my parents that I would have to go to the hospital right away to have my appendix removed.

I wasn’t particularly frightened, since Tata had often described the hospital as a wonderful place where you can pick up the phone at any time to order ice cream. The only reason I was upset was because I was not allowed to get dressed for the trip. The very idea of going out in public without the proper clothes filled me with acute embarrassment. My father, however, ignored my protests, put a blanket around me, and carried me into a taxi. Mother, who was suffering from neuritis in her shoulder and arm, got out of her bed to accompany us to the hospital. I could see Mother’s concern for me, mingled with the physical pain she was enduring.

It was dark when we arrived at Doctors Hospital on the Upper East Side of Manhattan and the situation there was not at all what I had been led to expect—certainly not private phones and ice cream. I don’t remember any pain, only fear at the increasing number of doctors and nurses examining me and trying to stick needles in my arms. They decided that it was an emergency and scheduled the operation for ten o’clock that evening. By this time I knew that whatever I had been told had been a lie. I wanted no part of the hospital and tried to tell them that I was fine, couldn’t they please forget about the operation and let me go home.

Surrounded by strangers who ignored my pleas, I became increasingly tearful until a young Asian nurse bent down next to my bed and put her arms around me. She spoke softly and made me feel that she really cared. I wanted to spend the rest of my life being comforted by her. Thanks to her I let them do the unthinkable—stick a needle in my arm with a minimum of fuss. As was the case with so many of the guardian angels who would appear to me in a moment of crisis and then disappear, I never saw her again.

After the operation, I emerged from a very real dream state in which many people that I had known were coming by to see me. When my thoughts cleared and the post-operative discomfort began, I found myself in a white room with two single beds and a wooden screen with a dim light behind it. I looked over at the other bed and was surprised to see Lucy, sleeping peacefully. I hadn’t known that Mother had arranged for her to spend the night in the hospital with me; I’m sure she thought it would be comforting for me to awaken with someone I knew in the room. I started to cry and asked Lucy to come over to me, but she wouldn’t. She whispered, “You mustn’t speak to me because your nurse might get angry if I interfere with her job.”

The nurse heard me wake up, came out from behind the screen and handed me a basin to throw up in while Lucy lay silently a few feet away. Once again I wondered why she refused to protect and comfort me. There were so many things that I couldn’t understand.

At dawn Lucy went home to take care of my brother, and another private nurse came on duty to care for me. I didn’t cry when she gave me an injection every four hours; on some level of consciousness I must have understood that the drugs took away the pain for a little while.

My aunt Tata came to visit me every day. She was wonderful to be with because she always treated me like a little adult. My first morning in the hospital, she sent me one of the best presents of my life—a whole rose bush. It was covered with dozens of little pink roses and sat on the windowsill where I could look at it all day. My mother told Tata that it was silly to give such an expensive gift to a child. But it made me feel special.

One afternoon a few days later, my father came to see me for the first time, with a gift in his arms. Mother came with him.

I had no idea, as I unwrapped the package, that something was about to go terribly wrong. I had just taken the present out of the box when my mother gave me the news that a family that we knew well would come to visit me in the hospital. The words were barely out of her mouth when my world suddenly went into slow motion. I became frozen with terror and could no longer speak.

I had no explanation for what was happening to me. All I knew was that something within me had suddenly snapped and the thought of any visitors, even those I knew well and had always liked, struck terror in my heart. Nobody knew at the time, least of all me, that as a consequence of Mr. Fuller’s abuse, what I was experiencing in the hospital that day was the first of several nervous breakdowns.

Even though I was paralyzed by fear, my parents remained oblivious to the storm silently brewing inside me. Father was angry at my not acknowledging the new brown leather bedroom slippers he had brought me, and Mother was furious that I was too rude to thank my father for his gift. They promptly left their mute and ungrateful child alone with the nurse.

The next day, when our friends showed up, was not a pleasant time for any of us. I was no longer frozen but had reached a state of hysteria which embarrassed my parents and left the visitors wondering what they had done wrong.

When I went home after ten days in the hospital, I took the terror with me. It was no longer possible for me to go anywhere outside of the house without panic setting in. We couldn’t receive visitors without my hiding out in the farthest corner of the apartment. If I had to go to a store, I would have to be walked around the block several times before I could finally enter the building.

Mother had difficulty understanding my behavior, which upset me because I could no longer be her perfect little friend, and my father had no idea how to handle the situation. So they left it to Lucy to cope with me as best she could.

Richard had somehow gotten it into his head that I might die from my appendix operation and had temporary feelings of guilt. The day I came home from the hospital, he was nice to me—almost solicitous—for the first time in my life, and it felt good. But about twenty minutes later, when he realized that I was not going to die and that I was the same little brother he had always resented, it was all over. I had always assumed that his abusive behavior was normal, that it was the way all older brothers treated their younger siblings. For the first time in my eight years I clearly saw what might have been. It made me sad.

Spring: First Holy Communion

A few months later, in the springtime, in spite of the emotional breakdown I had had in the hospital, my parents decided it was time for me to make my First Holy Communion. We were not a religious family but they felt it was important for their children to receive the sacraments of the Catholic Church. I was informed that I would have to go through a training period to learn the fundamentals of the church and, more importantly, make sure that my soul was pure enough to receive the sacraments.

I had always been intrigued by spirituality and the idea that someone knew the secrets of the universe, and had wanted to send away for booklets by groups such as the Rosicrucians, who advertised in my comic books, though I never did. This fascination was probably the reason that I peacefully followed my mother on my first visit to the Helpers of the Holy Souls in New York City.

We rang the convent bell and a tall, solemn woman in long black robes silently opened the ornate wooden doors. I held on to Mother’s hand as we left the sunshine outside and entered the darkness. The only light was filtered through the religious figures in the stained glass windows. Mother and I sat close together in the long entryway, which was lined with wooden benches. For once, I felt more curiosity than anxiety while we waited to meet the Mother Superior, who would enroll me in my classes.

Within a week I joined a class of about twenty children. We rarely interacted, just quietly studied our lessons and sat for long periods of time in silent contemplation. The nuns turned out to be nameless, faceless, black-robed figures with cold discipline flowing through their veins. A sympathetic word or touch for the children was not a part of the program.

Strangely enough, I was taught nothing about the real meaning of the Catholic faith or God’s love. As far as I knew, religion was a dull textbook of rules and the Mass was just a boring forty-five minutes while the priest showed his back to the congregation and mumbled in a foreign language.

The last three days before the ceremony were intense; it was the last chance for us children to mend our ways. We contemplated our faults and went to confession on each of those days, to be sure that we had been properly absolved of our sins. But how could I ever be sure that I was perfect enough to receive Holy Communion?

It was a solemn moment when the Mother Superior called me into her tiny office. She sat with a large crucifix behind her head and asked me about my parents, and if they went to church on Sundays. When I answered truthfully that they did not strictly follow the rules of the Church, the old nun informed me that it was my responsibility to see that they went to Mass every Sunday and confession at least once a month.

I cautiously approached my parents and told them what the nun had said. Mother and Father were not happy. They said that the nuns were being paid to see that I made my First Communion, and the rest was none of their business.

Now my dilemma was multiplied. Not only did I have to worry about my own perfection, but had my parents’ souls on my conscience as well. I knew it was a losing battle and that I would only further irritate my parents if I persisted.

As the final day drew near, I was told that a little girl and I had been chosen to go up to the altar during the ceremony to recite a special prayer. Did this mean that I was ready? Or would I have to find out on the day itself, when God would decide whether or not to strike me down as the priest put the body of Christ on my tongue?

When the big day arrived, I was dressed in a dark suit with short pants and a white bow tied around my arm. I was taken to the convent early, and made to sit in a large circle with the other children. I sat facing the large windows, wishing that I could miraculously fly away. Surely I could not be perfect enough for this solemn religious occasion.

Terror once again enveloped me as I fought back the tears. The children across the way looked up from their silent contemplation when my sobbing became audible. No one moved for the longest time. Finally a little girl came over from the other side of the room and put her arms around me in a motherly way.

I was trembling inside as we filed into the chapel. My parents, Tata, and Richard were already seated with the other families.

Shortly before the moment of truth, the anticipation became too much for me. I knelt down and fainted. I regained consciousness to the humiliation of being dragged up the aisle by a large nun, and was unceremoniously laid out on the floor of the vestibule.

Mother was mortified at the scene I had caused, but the nuns were not to be fooled with. As soon as I could sit up, they took me back into the chapel where I received the sacraments with the other children and recited the special prayer at the altar. I could only hope that God had been too busy elsewhere to notice me receiving the communion wafer. I also prayed that since I survived that, and recited the prayer perfectly, my parents would ignore the embarrassment I had caused them by fainting in public.

In years to come, I discovered that a friend named Ronnie, who had made his First Communion at the same time, had been told by the Mother Superior that if his mother did not divorce his stepfather and remarry his father, she would burn in hell for all eternity. Ronnie didn’t faint in church, but within weeks he had a nervous breakdown.

Soon after my First Communion, my parents began to plan our annual summer trip to France—where, at my Aunt Mimy’s beautiful summer home, La Richardière, yet another emotional trauma awaited me.

Summer: The Rabbit

Aunt Mimy had been a childhood playmate of my father. Her family had little money, so the moment she was old enough she married my father’s very rich and much older uncle, Louis Cointreau, who died shortly after she gave birth to their son, Pierre. Then she was able to marry for love, and wed the Count D’Epenoux, who had a beautiful château filled with exquisite museum-quality furniture. They lived part of the year in his château, part of the year at Aunt Mimy’s summer estate, and part of the year in Paris.

La Richardière, Aunt Mimy’s summer estate, not far from Maman Geneviève’s château in France, was a massive house well hidden from public view by a long, winding road, and was surrounded by many acres of woods and gardens where my father had enjoyed hunting parties when he was young.

As far as I was concerned Aunt Mimy could do no wrong. She had a voice and personality that was a cross between Ethel Merman and Maria Callas, and a large body that she always insisted was on a diet. In spite of her weight, Mimy had a pretty face with delicate features, and a seductive smile that was not dimmed by the fact that her teeth were slightly discolored from smoking the Spud menthol cigarettes my mother brought her from America.

Her electric personality mesmerized me; at nine years old, I was already fascinated by larger-than-life characters. I was used to catering to adults and enjoyed being near the aura of such a glamorous woman. And Aunt Mimy was my godmother, so she noticed me a bit more than my brother.

My brother Richard and I were only two years apart, but he was always much larger than I. He was built stout—wide and strong—while I was slender, more bones than muscle. In spite of his abuse, I still wanted to follow him around and tried to be his buddy.

One sunny summer day at La Richardière, Richard was acting mysteriously and implying that something interesting was going to happen soon. As usual he made it sound enticing and then pushed me away.

I surreptitiously followed my brother when he went through a door leading to the dark basement of the house and disappeared. The entrance was dimly lit and muffled voices came from afar. I traced the sounds through a labyrinth of concrete and stone dungeons until I found a doorway. I peeked cautiously through the opening, and saw a large bare stone room with several men standing at the far end in a semicircle. Richard was in their midst, looking up at something with an anticipatory smile on his face. A cold feeling of dread came over me as my eyes adjusted to the light and I focused on the thing hanging by its hind legs above my brother’s head. It was pure white and squirming—the softness of its fur in sharp contrast to the hardness of the men and the stone walls. At first I didn’t understand. I stood frozen outside the doorway, my eyes glued to the ecstatic expression on my brother’s face.

The first move was very sudden. And then I understood. One swift club on the back of the bunny’s head and then a quick thrust with a sharp knife to gouge out its left eye so it would bleed to death. The creature was still wriggling around and trying to free itself, so the man gave it another whack on the back of the head.

They were so intent upon their mission that no one had seen me in the doorway. They did not know the sickness in my body as I slowly backed away. I couldn’t run. I could barely walk back out into the sunshine. All I wanted was to find my mother.

When I saw her she was reclining on a lounge chair in the back of the house, reading a book. Knowing that she would be displeased if I were sick in front of her, I moved cautiously towards her and sat down on the stone floor nearby.

“Mummy, I just saw something awful.”

“What am I going to do with you? You’re always nervous about something!”

“But it was really awful, Mummy.”

I knew that my sensitivity sometimes tried my mother’s patience, so I was not surprised that she gave no response and returned to her book. I walked around the corner to be alone with my thoughts. Maybe if I had been a little quicker I could have stopped them. But they were so big. And Richard would have been angry with me too.

Pale and unhappy, I rested against a large tree and tried to figure out how my brother could enjoy watching an animal suffer. After a while, I became aware of someone looking down at me—a tall, blonde German.

German prisoners of war had been allowed to go to work for very low wages in French households at the end of World War II. Aunt Mimy, never one to miss a bargain with the dozens of people she needed to run her estate, had hired some of them to work in the fields and gardens.

At first I was uneasy. I had heard many terrible stories about the Germans. Also, I had only seen this ex-prisoner-of-war working on the land, but had never spoken to him.

The man knelt down and gently asked me my name.

“My name is Jacques-Henri. And I just saw the most awful thing.”

“You don’t look very well. Why don’t you tell me about this awful thing?”

The young German listened intently to as much of the story as I could articulate and agreed that it was a terrible thing to have witnessed. He said that I was a brave young man to have wanted to save the rabbit but there was really nothing that I could have done. This was the fate of all the rabbits that were being raised for food on the estate.

He was kind, not at all the way the Germans had been portrayed. And although he made me feel better by explaining what I had just seen, I never understood why the rabbit had to suffer such a cruel death.

When the bell rang for lunch, I thanked my new friend and ran back into the house. As hard as I looked for him, I never saw him again.

A few days after the incident with the rabbit, knowing how difficult it was for my mother to deal with my emotional problems, I carefully planned a whole scenario. I was so excited about a wonderful moment that I was creating, a secret gift of gratitude that I would give to my mother. No one else ever need know about it. She couldn’t help but forgive my imperfection and love me more for it.

That evening I could no longer wait. It had to be tonight when she came in to say goodnight to me in the pretty blue and white flowered room at La Richardière.

Tonight I would put on my pajamas, brush my teeth, wash my face, carefully comb my hair, get into bed, and wait for Mother. If the nanny was around, I would ask her to please leave us alone for a while. Richard would not be in the way, since he was allowed to stay up later. I was so sure that nothing could go wrong. My heart was pounding with anticipation.

How wonderful it felt to be surrounded by the crisp linen sheets and the warmth of the blankets while I waited for her to appear. Oh, my God, she looked so perfect as she walked in that I almost lost my nerve. The nanny was slightly miffed and reluctantly left the room when I announced that I wanted to be alone with my mother for a little while.

I started slowly. “Mummy, I want to thank you for being so good to me since my operation. I’ve been so nervous all the time but I know I’m getting better and I wanted to thank you for being so patient with me.”

She gave an embarrassed little laugh as she quickly got up to go, and said, “Yes, sometimes one feels like saying ‘Thank you’ for something.”

Somehow I was not too surprised that my mother didn’t seem to understand the importance of the moment. I didn’t really understand it too well myself. Maybe I hadn’t said it well enough. I knew that I could never try again. I had done my best and the moment was gone. Strangely, there was a kind of afterglow from simply having said the words.

The Doctor’s Report

By the time we left La Richardière, my parents could no longer ignore my escalating emotional problems. I had become even more obsessed with my own cleanliness and perfection, and was increasingly fearful of the outside world. Since my parents knew nothing about what Mr. Fuller had done to me, they were confused by my neurotic behavior, and were finally forced to seek professional help.

That summer, Mother took me to see a doctor at the Children’s Hospital in Paris. Several child psychologists put me through a battery of tests, but in those days child molestation was not as openly acknowledged as it is today, and no one asked me the most important question. My “secret,” being sexually abused and raped by Mr. Fuller, was not brought to light.

So when the hospital wrote a letter with their findings for my parents to give to a doctor upon our return to New York, their opinion was:

This child is suffering from an obsessive neurosis. He has always been scrupulous, full of doubts and fanatical about being perfect. He has already suffered from several compulsive obsessions (perfection in his grooming, perfection in his schoolwork, etc.). Very fixated on his mother with a striking ambivalence.

He suffers from acute anxiety attacks (fear of going into class, fear of entering a public place) which were triggered by two emotional shocks at several weeks’ interval: an appendectomy and a first communion which seemed to awaken all his feelings of guilt.

The Rorschach test shows a basic anxiety with obsessive elements. The TAT by Murray shows an obvious castration complex.

A course of psychoanalysis appears to me to be indispensable and urgent. The parents understand the situation and are committed to having their son undergo the necessary treatment.

Back in New York, my parents’ physician, whom I knew well, had a talk with me at our home. It consisted of his patiently urging me to look into his face and say, “Hello.” Once he had accomplished that task he announced in a loud voice that I no longer needed any psychiatric help.

The subject was never brought up again.