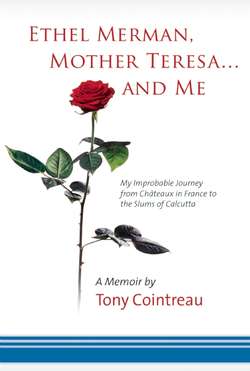

Читать книгу Ethel Merman, Mother Teresa...and Me - Tony Cointreau - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHE WAR

It was only as an adult, going through my parents’ personal papers and letters after their deaths, that I came to realize what extraordinary events they had lived through before my birth. The people that I had thought of as just my parents, involved in international business and a seemingly frivolous social life, had actually survived two world wars in Europe, and, like many people of their generation, had had experiences as dramatic as any that I had seen in the movies.

My father was well over the age limit to re-enlist when France entered World War II, but in 1940, at the age of thirty-nine, he managed to convince the French army that he would be a welcome addition to their ranks.

He knew he might have to leave the family at any moment to join his battalion, but my parents’ main concern was for the safety of my brother, Richard, who was only a year old. As reports came in that the Germans were approaching Angers, my parents decided that the wisest—but by far the most difficult—course of action would be for Mother to take Richard to America. This meant that she would have to drive through France, Spain, and Portugal to Lisbon in time to board the last ship bound for America.

What it was like to escape from Europe in wartime with baby Richard and his nurse, Lucy, was eloquently expressed by my mother herself in letters that she took time to write to her mother and Ashie during her drive across war-torn Europe. Here are excerpts from her letters.

In her first letter, dated June 13, 1940, Mother wrote:

Really, darlings, I never could attempt writing you all the doings, emotions and activity of my present life—it’s bedlam. Amongst everything have dashed to Prefecture with necessary papers filled out so I can get permit for Lucy and myself to leave country. Today must go to police station for permit of circulation so I can be allowed on the roads to Bordeaux. You can never imagine all the red tape we have to go through—I want everything in order so that when we can leave nothing will delay us.

The trip will be hard, very hard, I’m not kidding myself. Traffic in main streets here is like traffic in N.Y. side streets at theater time. Files and files of cars all covered with mattresses, arriving from Paris and suburbs and going Lord knows where. Here in Angers we are already jam packed—so they have to go on and on and sleep under the stars.

Barrages of soldiers stopping everyone to examine our papers. It’s real war now—but everyone stays calm—the French spirit is admirable—Jacques is always a wonder of optimism and courage.

On June 16th she wrote:

Since my last letter everything has changed in my life. Friday night the 14th at 10 p.m. we heard the bridges on the Loire would shortly be blown up so we had to leave as soon as humanly possible. That night I got about three hours of sleep. Next morning—wild dash to Prefecture to get my necessary papers which we were awaiting. At 3:30 p.m. we had to go back to Prefecture with suitcases strapped on top and in car. At 3:45 p.m. we were off.

Over the years, I heard one of my father’s first cousins, Pierre, who was a teenager when Mother left Angers, speak in awe about seeing my mother come down the stairs of her home that day. He said it was an impression that would last a lifetime—she was impeccably groomed, not a hair out of place, and wore spotless white gloves. She looked as though she were on her way to a tea party rather than setting out on a perilous journey.

For the first time in years, Mother was forced to travel with just a few suitcases instead of wardrobe trunks, but she wrote, “My fur coats are on my LIST.” However, being of a practical nature, Mother also made sure that she had a hundred liters of gasoline in the car since it would be next to impossible to find any on the roads.

Her letter continues:

I shan’t go into details now of feelings I had leaving Jacques behind me, and my beautiful home with everything I own left just as it was, which I never hope to find again. I can’t let myself go. I need every bit of strength and courage I have to carry off our trip. Our little darling is a grave responsibility.

Mother’s first stop would be in Cognac, where André Renaud, an old friend of the family and the owner of Remy Martin Cognac, lived.

Leaving Angers was longest as there were only single files of cars allowed to cross bridges in one direction at a time. After that I drove as I had never driven before in my life—between 80 and 110 kilometers an hour. Maybe it doesn’t sound much to you but you have no idea how the roads were crowded, just files and files of columns of refugees.

At 9:15 exactly we were in Cognac and I had found André Renaud and his family. It was such a relief—no words to describe it even—finding Renaud and not having to sleep somewhere in the car as thousands of others had to.

Mr. Renaud gave her the different currencies from his safe that he knew she would need to successfully complete her journey through Spain and Portugal.

It’s lucky Ashie has album of baby and pictures of our interior of home, as I couldn’t save anything. At least we will have tangible souvenir—but I don’t give a d---about that. It’s funny how little possessions count—only hope Jacques keeps safe.

All the Cointreaus have gone different directions— sauve qui peut! [Every man for himself!] Will keep you informed when I know my plans.

On June 22, Mother wrote from San Sebastian, Spain:

Just one week ago today since I left Jacques and our lovely home. One week which seems like a hundred years—Since then all communications were cut off from that part of country and I have no news of Jacques or anyone.

The Germans occupied Angers on Tuesday [only four days after her departure]. I wish we hadn’t left so much good champagne in our cellar for them. I had to leave everything just as it was—didn’t have time to take with me any of my silver or linens. I guess everything we had is gone for good.

I know Jacques was preparing to move back with the rest of Quartermasters Corps, but as all that part of country has been taken, they may all be prisoners now—it’s too awful to even think about.

You can’t imagine how lonesome it feels being so far from everyone—cut off from all communications, and all the time the worry over Jacques.

Wherever she went through war-torn Europe, the struggle for visas was intense, as people attempted to escape before the German army could reach them. Mother was almost crushed and her clothes were torn by the mobs outside the Spanish Consulate. But through it all she fought like a tigress and no matter what, made sure she looked her best at all times—ammunition she knew she might need to charm officials along the way.

Bridges and borders closed immediately behind her:

We got to Hendaye and joined the files of cars waiting their turn to cross frontier, one mile long from bridge. More military papers to be gotten—special permit to take car out of country—inspection of baggage. Anyway by 5:00 p.m. we were on bridge. French gates closed behind us!

Altogether it took nine days for Mother, Richard, and Lucy to make the trip from Angers to Lisbon, where they finally boarded a packed ship with the relatively few fortunate souls able to book passage to America. Once they were safely on board my mother realized that the nausea she had been experiencing had not been due to the smell of fish in the port city of Lisbon but to the fact that she was pregnant with me. With everything else she had to contend with at the time, this was not an event that Mother welcomed. According to Lucy, Mother vented her frustration by breaking a hairbrush over Lucy’s head. Naturally, it was Lucy’s hairbrush, not Mother’s own.