Читать книгу Stranger at the Gates - Tracy Sugarman - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

NEW FOREWORD

ОглавлениеDuring the summer of 1964 more than a thousand college students from across this country converged upon the state of Mississippi as part of the Freedom Summer Project. Mostly young, white, middle-class kids, they spent the summer in the homes of poor sharecroppers and other laborers. They were answering a call from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) for volunteers to spend a summer helping the black population in a racially oppressive Mississippi gain their freedom by registering to vote and attending Freedom Schools.

In 1964, blacks made up nearly 40 percent of the total state population, yet only approximately 5 percent were registered to vote—and only a few of that number even dared to show up at a polling place on election day. Voting was not a privilege granted to blacks but an action that, if practiced, invoked a fear of reprisals that could have meant death to an individual or a group.

The young came in sandals, with pens, pencils, and a willing spirit to correct a political wrong: a blatant history of injustice against a segmented group of people. When the group arrived in Mississippi in June, three civil rights volunteers in Neshoba County were already missing, presumed victims of the Ku Klux Klan, who were bent on keeping things the way they were at all costs—usually through violence. When, after several weeks, the worst was confirmed—the three young civil rights volunteers were dead—the movement was not deterred. Instead, it picked up momentum.

Those three disappearances and then confirmed deaths brought national media attention to the plight of black Mississippians. Not only were voting rights severely compromised, but there was not one black elected official at the state level or in any of Mississippi’s eighty-two counties except for the all-black town of Mound Bayou.

The young volunteers of the Freedom Summer Project played a key role in assisting black Mississippians to organize the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP). MFDP, a parallel party to the Mississippi Democratic Party, planned to challenge the regular all-white Mississippi delegation to the Democratic National Convention—a challenge based on the fact that the black population was being denied participation in the political process at local precincts in the selection of delegates to the county, district, and state conventions.

SNCC organizers had helped black citizens set up the political process for the MFDP across the state, and on April 6, 1964, MFDP held its state convention in the Masonic Temple in Jackson, Mississippi. During the convention—where the influential activist Ella Baker was the speaker— sixty-eight delegates were selected to attend the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey, to claim their right to be seated.

The first step in the MFDP seating challenge process was a hearing before the National Democratic Party Credentials Committee. Although there were testimonies by Aaron E. Henry of the MFDP and by national civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the testimony that mattered most came from a sharecropper, Fannie Lou Hamer. In a resonant voice, Hamer told the committee about her eviction from her plantation home after she made an application to register to vote in Sunflower County. Hamer captured the full attention of the members of the Credentials Committee and of the national TV audience when she went on to describe the brutal beating she suffered in 1963 when she and other activists were falsely accused and thrown into a Montgomery County jail.

So damaging was Fannie Lou Hamer’s testimony that President Lyndon B. Johnson called a press conference, hoping to get her off TV. When the evening news insisted on carrying the full Hamer testimony, a furious President Johnson sent his potential vice-president, Hubert H. Humphrey, to offer the MFDP a compromise giving them two seats “at large.” Regarded by the MFDP as “nothing” because it would change “nothing” in Mississippi for the black population, the offer was unanimously rejected by the delegates. The regular all-white Mississippi delegation was asked to pledge its support to the National Democratic Party ticket, but the delegation refused and went home. In its absence the MFDP delegates began filling the vacant convention seats under the Mississippi banner. Meanwhile, President Johnson, worried that a floor fight could cost him support of the southern wing of the Democratic Party, arranged to have the convention nominate him by acclimation, and no delegate vote on the convention floor was taken,

While the MFDP did not succeed in unseating the regular Mississippi Democratic Party delegation in Atlantic City in 1964, the challenge again attracted national media attention to the shameful conditions under which the state of Mississippi was forcing its black population to live. In addition, the National Democratic Party pledged not to seat a segregated state delegation in the future. In the 1964 presidential election, Mississippi and the rest of the Deep South went Republican. This was just the tip of the iceberg.

Many of the successes of that hot summer of 1964 were thanks to the volunteers who spent the summer living in crowded and stifling homes with outside toilets, and who walked endless miles on unpaved roads, daily facing fear and danger in an attempt to register black voters with the MFDP and begin to correct the atrocity of inequality.

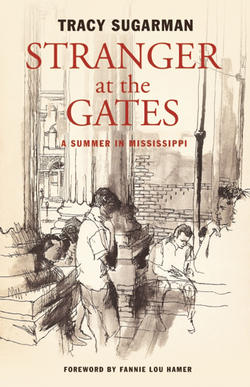

Fifty years later, we should welcome the reprinting of Tracy Sugarman’s memoir, Stranger at the Gates. Sugarman, a writer and illustrator who died in 2013, was a lifelong activist and a friend of Fannie Lou Hamer. He joined the students as a volunteer in Mississippi—not only participating but observing, taking notes, and making his wonderful drawings. His book is a vivid, on-the-spot account of a time when lives were lost, lives were changed, and the word freedom took on a new meaning.

Charles McLaurin

Indianola, Mississippi, 2014