Читать книгу Stranger at the Gates - Tracy Sugarman - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

PREFACE

ОглавлениеAs if released by the shattering frenzy of the struggle, gusting winds of change raced through the postwar years. They altered the face of Africa and Asia and buffeted a Europe that was struggling to stand. The death of fascism heralded a new beginning. A surging tide of expectation touched the disinherited everywhere. In America, the Negro, who had been waiting a hundred years for the death of “Jim Crow,” shuffled his G.I. boots impatiently and stared hard at his democratic society.

From the moment the U.S. Supreme Court declared in 1954 that “separate but equal” schools were unconstitutional, the American Negro launched a sustained assault on discrimination and segregation. Adapting the Gandhian tactic of nonviolence, he challenged his society with his cry of “Freedom Now!” One hundred years after Appomattox, his “sit-ins” and “Freedom Rides,” “wade-ins” and “kneel-ins” were defying the legal evasions and moral pretensions of America. Against police dogs and fire hoses, vigilante shotguns and torches, he placed his body in eloquent testimony to his belief in Christianity and the United States Constitution.

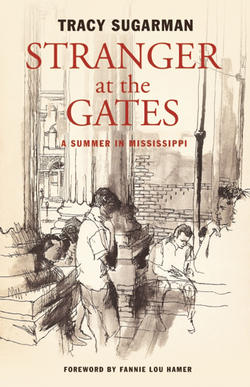

Like so many others in the United States, I was moved by this sacrifice and appalled that in this land it should be necessary. From the moment I returned from Normandy and left the U.S. Navy in 1945, I had worked as an illustrator. Whenever possible, I had sought out the reportorial assignment. Whether in “cracking plants” or aseptic laboratories, assembly lines or amid the dusty roar of construction, I had toted my sketchbook, recording the face of postwar America. The mounting urgency of the racial crisis became for me and my wife a crisis of conscience as well. In some way we knew we must do what we could to help. Even as President Kennedy urged a sluggish Congress to enact relief for the Negro American through the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Civil Rights Movement was preparing an attack on the most inviolable fortress of segregation in the United States. Against the Klan, the White Citizens Councils, and the might of a hostile society’s police, a thousand unarmed students prepared to move into Mississippi. They were to receive their orientation at the Western College for Women in Oxford, Ohio.

In family council, we decided that this could be our way to help. June would maintain our home base with our children, raising funds and building support for the Mississippi Summer Project. And I would accompany the students to Mississippi, recording their “Odyssey” for the country to see. Pamela Illot of CBS News assured me that she would use my pictures and tapes. The result was her lovely half-hour television documentary, “How Beautiful on the Mountains,” that appeared on her series, “Lamp Unto My Feet.” In Washington the U.S.I.A. magazine, Al Hayat, promised to use my drawings and my notes to tell the civil rights story overseas. I left for Oxford feeling that there would be an audience for the pictures I wanted to draw. In the months following that long summer, the drawings helped carry the implications of the struggle in magazines sent by the U.S. to India, Africa, and Europe. At home they appeared in newspapers, magazines, and in exhibitions on many campuses and in many cities.

No one who went to Mississippi in 1964 returned the same. Some were disoriented, some embittered, some exalted by a new vision of America. I came home from the dusty roads of the Delta with a deeper understanding of patriotism, an unshakeable respect for commitment, and an abiding belief in the power of love.

T.S.

Westport, Connecticut

April, 1966