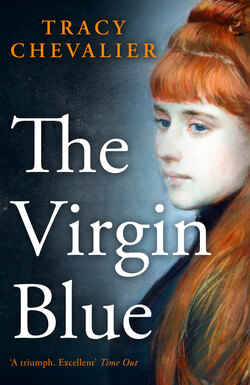

Читать книгу The Virgin Blue - Tracy Chevalier - Страница 7

Оглавление

She was called Isabelle, and when she was a small girl her hair changed colour in the time it takes a bird to call to its mate.

That summer the Duc de l’Aigle brought a statue of the Virgin and Child and a pot of paint back from Paris for the niche over the church door. A feast was held in the village the day the statue was installed. Isabelle sat at the bottom of a ladder watching Jean Tournier paint the niche a deep blue the colour of the clear evening sky. As he finished, the sun appeared from behind a wall of clouds and lit up the blue so brightly that Isabelle clasped her hands behind her neck and squeezed her elbows against her chest. When its rays reached her, they touched her hair with a halo of copper that remained even when the sun had gone. From that day she was called La Rousse after the Virgin Mary.

The nickname lost its affection when Monsieur Marcel arrived in the village a few years later, hands stained with tannin and words borrowed from Calvin. In his first sermon, in woods out of sight of the village priest, he told them that the Virgin was barring their way to the Truth.

—La Rousse has been defiled by the statues, the candles, the trinkets. She is contaminated! he proclaimed. She stands between you and God!

The villagers turned to stare at Isabelle. She clutched her mother’s arm.

How can he know? she thought. Only Maman knows.

Her mother would not have told him that Isabelle had begun to bleed that day and now had a rough cloth tied between her legs and a pillow of pain in her stomach. Les fleurs, her mother had called it, special flowers from God, a gift she was to keep quiet about because it set her apart. She looked up at her mother, who was frowning at Monsieur Marcel and had opened her mouth as if to speak. Isabelle squeezed her arm and Maman shut her mouth into a tight line.

Afterwards she walked back between her mother and her sister Marie, their twin brothers following more slowly. The other village children lagged behind them at first, whispering. Eventually, bold with curiosity, a boy ran up and grabbed a handful of Isabelle’s hair.

—Did you hear him, La Rousse? You’re dirty! he shouted.

Isabelle shrieked. Petit Henri and Gérard jumped to defend her, pleased to be useful at last.

The next day Isabelle began wearing a headcloth, every chestnut strand wound out of sight, long before other girls her age.

By the time Isabelle was fourteen two cypress trees were growing in a sunny patch near the house. Each time, Petit Henri and Gérard made the trip all the way to Barre-les-Cévennes, a two-day walk, to find one.

The first tree was Marie’s. She grew so big all the village women said she must be carrying twins; but Maman’s probing fingers felt only one head, though a large one. Maman worried about the size of the head.

—Would that it were twins, she muttered to Isabelle. Then it would be easier.

When the time came Maman sent all the men away: husband, father, brothers. It was a bitterly cold night, a strong wind blowing snow into drifts against the house, the stone walls, the clumps of dead rye. The men were slow to leave the fire until they heard Marie’s first scream: strong men, accustomed to the sounds of slaughtered pigs, the human tone drove them away quickly.

Isabelle had helped her mother at birthings before, but always in the presence of other women visiting to sing and tell stories. Now the cold kept them away and she and Maman were alone. She stared at her sister, immobile beneath a huge belly, shivering and sweating and screaming. Her mother’s face was tight and anxious; she said little.

Throughout the night Isabelle held Marie’s hand, squeezed it during contractions, and wiped her forehead with a damp cloth. She prayed for her, silently appealing to the Virgin and to Saint Margaret to protect her sister, all the while feeling guilty: Monsieur Marcel had told them the Virgin and all the saints were powerless and should not be called upon. None of his words comforted her now. Only the old prayers made sense.

—The head is too big, Maman pronounced finally. We have to cut.

—Non, Maman, Marie and Isabelle whispered in unison. Marie’s eyes were wild and dilated. In desperation she began to push again, weeping and gasping. Isabelle heard the sound of flesh tearing; Marie shrieked before going limp and grey. The head appeared in a river of blood, black and misshapen, and when Maman pulled the baby out it was already dead, the cord tight around its neck. It was a girl.

The men returned when they saw the fire, smoke from the bloody straw billowing high into the morning air.

They buried mother and child in a sunny spot where Marie had liked to sit when it was warm. The cypress tree was planted over her heart.

The blood left a faint trace on the floor that no amount of sweeping or scrubbing could erase.

The second tree was planted the following summer.

It was twilight, the hour of wolves, not the time for women to be walking on their own. Maman and Isabelle had been at a birthing at Felgérolles. Mother and baby had both lived, breaking a long string of deaths that had begun with Marie and her baby. This evening they had lingered, making the mother and child comfortable, listening to the other women singing and chatting, so that the sun had sunk behind Mont Lozère by the time Maman waved away cautions and invitations to stay the night and they started home.

The wolf lay across the path as if waiting for them. They stopped, set down their sacks, crossed themselves. The wolf did not move. They watched it for a moment, then Maman picked up her sack and took a step toward it. The wolf stood and Isabelle could see even in the dark that it was thin, its grey pelt mangy. Its eyes glowed yellow as if a candle were lit behind them, and it moved in an awkward, off-balance lope. Only when it was so close that Maman could almost reach out and touch the greasy fur did Isabelle see the foam around its mouth and understand. Everyone had seen animals struck with the madness: dogs running aimlessly, foam flecking their mouths, a new meanness in their eyes, their barks muffled. They avoided water; the surest protection from them, besides an axe, was a brimming bucket. Maman and Isabelle had nothing with them but herbs, linen and a knife.

As it leapt Maman raised her arm instinctively, saving twenty days of her life but wishing afterwards that she had let it rip out her throat quickly and mercifully. When it fell back, when the blood was streaking down Maman’s arm, the wolf looked at Isabelle briefly and disappeared into the dark without a sound.

While Maman told her husband and sons about the wolf with candles in its eyes, Isabelle cleaned the bite with water boiled with shepherd’s purse and laid cobwebs over it before binding the arm with soft wool. Maman refused to sit still, insisted on picking her plums, working in the kitchen garden, continuing as if she had not seen the truth shining in the wolf’s eyes. After a day her forearm had swelled to the same size as her upper arm, and the area around the wound went black. Isabelle made an omelette, added rosemary and sage, and mouthed a silent prayer over it. When she brought it to her mother she began to cry. Maman took the bowl from her and ate steadily, her eyes on Isabelle, tasting death in the sage, until the omelette was gone.

Fifteen days later she was drinking water when her throat began to contract in spasms, pumping water down the front of her dress. She looked at the black patch spreading on her chest, then sat in the late summer sun on the bench next to the door.

Fever came fast, and so furious that Isabelle prayed death would come as swiftly to relieve her. But Maman fought, sweating and shouting in her delirium, for four days. On the last day, when the priest from Le Pont de Montvert arrived to perform the last rites, Isabelle held a broom across the doorway and spat at him until he left. Only when Monsieur Marcel arrived did she drop the broom and stand by to let him pass.

Four days later the twins returned with the second cypress tree.

The crowd gathered in front of the church was not used to victory, nor familiar with the conduct of celebration. The priest had finally slipped away three days before. They were sure now that he was gone – the woodcutter Pierre La Forêt had seen him miles away, all the possessions he could carry piled on his back.

The early winter snow covered the smooth parts of the ground with a thin gauze, wrecked in places by leaves and rocks. There was more to come, with the sky the colour of pewter to the north, up beyond the summit of Mont Lozère. A layer of white lay on the thick granite tiles of the church roof. The building was empty. No mass had been said there since the harvest: attendance had dropped as Monsieur Marcel and his followers grew more confident.

Isabelle stood among her neighbours listening to Monsieur Marcel, who paced in front of the door, severe in his black clothes and silver hair. Only his red-stained hands undermined his commanding presence, a reminder to them that he was after all simply a cobbler.

When he spoke he focused on a point over the crowd’s head.

—This place of worship has been the scene of corruption. It is in safe hands now. It is in your hands. He gestured before him as if he were sowing seed. A hum rose from the crowd.

—It must be cleansed, he continued. Cleansed of its sin, of these idols. He waved a hand at the building behind him. Isabelle stared up at the Virgin, the blue behind the statue faded but with a power still to move her. She had already touched her forehead and her chest before she realized what she was doing and managed to stop without completing the cross. She glanced around to see if the gesture had been noticed. But her neighbours were looking at Monsieur Marcel, calling to him as he strode through them and continued up the hill toward the bank of dark cloud, tawny hands tucked behind him. He did not look back.

When he was gone the crowd grew louder, more agitated. Someone shouted:— The window! The cry was taken up. Above the door, a small circular window held the only piece of glass they had ever seen. The Duc de l’Aigle had installed it beneath the niche three summers ago, just before he was touched with the Truth by Calvin. From the outside the window was a dull brown, but from the inside it was green and yellow and blue, with a tiny dot of red in Eve’s hand. The Sin. Isabelle had not been inside the church for a long time, but she remembered the scene well, Eve’s look of desire, the serpent’s smile, Adam’s shame.

If they could have seen it once more, the sun lighting up the colours like a field dense with summer flowers, its beauty might have saved it. But there was no sun, and no entering the church: the priest had slipped a large padlock through the bolt across the door. They had not seen one before; several men had examined it, pulled at it, uncertain of its mechanism. An axe would have to be taken to it, carefully, to keep it intact.

Only the knowledge of the window’s value held them back. It belonged to the Duc, to whom they owed a quarter of their crops, in turn receiving protection, the assurance of a whisper in the ear of the King. The window and the statue were gifts from him. He might still value them.

No one knew for certain who threw the stone, though afterwards several people claimed they had. It struck the centre of the window and shattered it immediately. It was a sound so strange that the crowd hushed. They had not heard glass break before.

In the lull a boy ran over and picked up a shard of glass, then howled and threw it down.

—It bit me! he cried, holding up a bloody finger.

The shouting began again. The boy’s mother snatched him and pressed him to her.

—The devil! she screamed. It was the devil!

Etienne Tournier, hair like burnt hay, stepped forward with a long rake. He glanced back at his older brother, Jacques, who nodded. Etienne looked up at the statue and called loudly:— La Rousse!

The crowd shifted, steps sideways that left Isabelle standing alone. Etienne turned round with a smirk on his face, pale blue eyes resting on her like hands pressing into her.

He slid his hand down the handle and hoisted the rake up, letting the metal teeth descend and hover in front of her. They stared at each other. The crowd had gone quiet. Finally Isabelle grabbed the teeth; as she and Etienne held each end of the rake she felt a fire ignite below her belly.

He smiled and let go, his end tapping the ground. Isabelle grasped the pole and began walking her hands down it, lifting the teeth end of the rake into the air, until she reached him. As she looked up at the Virgin, Etienne took a step back and disappeared from her side. She could feel the press of the crowd, bunched together again, restless, murmuring.

—Do it, La Rousse! someone shouted. Do it!

In the crowd Isabelle’s brothers stood staring at the ground. She could not see her father, but if he was there as well he could not help her.

She took a deep breath and raised the rake. A shout rose with it, making her arm shake. She let the rake teeth rest to the left of the niche and looked around at the mass of bright red faces, unfamiliar now, hard and cold. She raised the rake, propped it against the base of the statue and pushed. It did not move.

The shouting became harsher as she began to push harder, tears pricking her eyes. The Child was staring into the distant sky, but Isabelle could feel the Virgin’s gaze on her.

—Forgive me, she whispered. Then she pulled the rake back and swung it as hard as she could at the statue. Metal hit stone with a dull clang and the face of the Virgin was sliced off, showering Isabelle and making the crowd shriek with laughter. Desperately she swung the rake again. The mortar loosened with the blow and the statue rocked a little.

—Again, La Rousse! a woman shouted.

I can’t do it again, Isabelle thought, but the sight of the red faces made her swing once more. The statue began to rock, the faceless woman rocking the child in her arms. Then it pitched forward and fell, the Virgin’s head hitting the ground first and shattering, the body thumping after. In the impact of the fall the Child was split from his mother and lay on the ground gazing upward. Isabelle dropped the rake and covered her face with her hands. There were loud cheers and whistles and the crowd surged forward to surround the broken statue.

When Isabelle took her hands from her face Etienne was standing in front of her. He smiled triumphantly, reached over and squeezed her breasts. Then he joined the crowd and began throwing dung at the blue niche.

I will never see such a colour again, she thought.

Petit Henri and Gérard needed little convincing. Though Isabelle blamed Monsieur Marcel’s persuasiveness, secretly she knew they would have gone anyway, even without his honeyed words.

—God will smile upon you, he had said solemnly. He has chosen you for this war. Fighting for your God, your religion, your freedom. You will return men of courage and strength.

—If you return at all, Henri du Moulin muttered angrily, words only Isabelle heard. He leased two fields of rye and two of potatoes, as well as a fine chestnut grove. He kept pigs and a herd of goats. He needed his sons; he couldn’t farm the land with only his daughter left to help him.

—I will plant fewer fields, he told Isabelle. Only one of rye, and I’ll give up some of the herd and a few pigs. Then I’ll only need one field of potatoes to feed them. I can get more animals again when the twins return.

They won’t come back, she thought. She had seen the light in their eyes as they left with other boys from Mont Lozère. They will go to Toulouse, to Paris, to Geneva to see Calvin. They will go to Spain, where men’s skin is black, or to the ocean on the edge of the world. But here, no, they will not come back here.

She gathered her courage one evening as her father sat sharpening a plough blade by the fire.

—Papa, she ventured. I could marry and we could live here and work with you.

With one word he stopped her.

—Who? he asked, whetting stone paused over the blade. The room was quiet without the rhythmic sound of metal against stone.

She turned her face away.

—We are alone, you and I, ma petite. His tone was gentle. But God is kinder than you think.

Isabelle clasped her neck nervously, still carrying the taste of communion in her mouth – rough, dry bread that remained in the back of her throat long after she had swallowed. Etienne reached up and pulled at her headcloth. He found the end, wound it around his hand and gave a sharp tug. She began to spin, turning and turning out of the cloth, her hair unfurling, seeing flashes of Etienne with a grim smile on his face, then her father’s chestnut trees, the fruit small and green and far out of reach.

When she was free of the cloth she stumbled, regained her balance, hesitated. She faced him but stepped backwards. He reached her in two strides, tripped her and tumbled on top of her. With one hand he pulled up her dress while the other buried itself in her hair, fingers splayed, pulling through like a comb to the ends, wrapping the hair around it as it had wound the cloth a moment earlier, until his fist was resting at the nape of her neck.

—La Rousse, he murmured. You’ve avoided me for a long time. Are you ready?

Isabelle hesitated, then nodded. Etienne pulled her head back by her hair to lift her chin up and bring her mouth to his.

—But the communion of the Pentecost is still in my mouth, she thought, and this is the Sin.

The Tourniers were the only family between Mont Lozère and Florac to own a Bible. Isabelle had seen it at services, when Jean Tournier carried it wrapped in linen and handed it ostentatiously to Monsieur Marcel. He watched it, fretful, throughout the service. It had cost him.

Monsieur Marcel laced his fingers together and held the book in the cradle of his arms, propped against the curve of his paunch. As he read he swayed from side to side as if he were drunk, though Isabelle knew he could not be, since he had forbidden wine. His eyes moved back and forth, and words appeared in his mouth, but it was not clear to her how they got there.

Once the Truth was established inside the old church, Monsieur Marcel had a Bible brought from Lyons, and Isabelle’s father built a wooden stand to hold it. Then the Tourniers’ Bible was no longer seen, though Etienne still bragged about it.

—Where do words come from? Isabelle asked him one day after service, ignoring the eyes on them, the glare from Etienne’s mother, Hannah. How does Monsieur Marcel get them from the Bible?

Etienne was tossing a stone from hand to hand. He flicked it away; it rustled to a stop in the leaves.

—They fly, he replied firmly. He opens his mouth and the black marks from the page fly to his mouth so quickly you can’t see them. Then he spits them out.

—Can you read?

—No, but I can write.

—What do you write?

—I write my name. And I can write your name, he added confidently.

—Show me. Teach me.

Etienne smiled, teeth half-showing. He took a fistful of her skirt and pulled.

—I will teach you, but you must pay, he said softly, his eyes narrowed till the blue barely showed.

It was the Sin again: chestnut leaves crackling in her ears, fear and pain, but also the fierce excitement of feeling the ground under her, the weight of his body on her.

—Yes, she said finally, looking away. But show me first.

He had to gather the materials secretly: the feather from a kestrel, its point cut and sharpened; the fragment of parchment stolen from a corner of one of the pages of the Bible; a dried mushroom that dissolved into black when mixed with water on a piece of slate. Then he led her up the mountain, away from their farms, to a granite boulder with a flat surface that reached her waist. They leaned against it.

Miraculously, he drew six marks to form ET.

Isabelle stared at it.

—I want to write my name, she said. Etienne handed her the feather and stood behind her, his body pressed against the length of her back. She could feel the hard growth at the base of his stomach and a flicker of fearful desire raced through her. He placed his hand over hers and guided it first to the ink, then to the parchment, pushing it to form the six marks. ET, she wrote. She compared the two.

—But they are the same, she said, puzzled. How can that be your name and my name both?

—You wrote it, so it is your name. You don’t know that? Whoever writes it, it is theirs.

—But—She stopped, and kept her mouth open, waiting for the marks to fly to her mouth. But when she spoke, it was his name that came out, not hers.

—Now you must pay, Etienne said, smiling. He pushed her over the boulder, stood behind her, and pulled her skirt up and his breeches down. He parted her legs with his knees and with his hand held her apart so that he could enter suddenly, with a quick thrust. Isabelle clung to the boulder as Etienne moved against her. Then with a shout he pushed her shoulders away, bending her forward so that her face and chest pressed hard against the rock.

After he withdrew she stood up shakily. The parchment had been pressed into her cheek and fluttered to the ground. Etienne looked at her face and grinned.

—You’ve written your name on your face, he said.

She had never been inside the Tourniers’ farm, though it was not far from her father’s, down along the river. It was the largest farm in the area apart from that of the Duc, who lived further down the valley, half a day’s walk towards Florac. It was said to have been built 100 years before, with additions over time: a pigsty, a threshing floor, a tiled roof to replace the thatch. Jean and his cousin Hannah had married late, had only three children, were careful, powerful, remote. Evening visits to their hearth were rare.

Despite their influence, Isabelle’s father had never been quiet about his scorn.

—They marry their cousins, Henri du Moulin scoffed. They give money to the church but they wouldn’t give a mouldy chestnut to a beggar. And they kiss three times, as if two were not enough.

The farm was spread along a slope in an L shape, the entrance in the crux, facing south. Etienne led her inside. His parents and two hired workers were planting in the fields; his sister, Susanne, was working at the bottom of the kitchen garden.

Inside it was quiet and still. All Isabelle could hear were the muted grunts of pigs. She admired the sty, the barn twice the size of her father’s. She stood in the common room, touching the long wooden table lightly with her fingertips as if to steady herself. The room was tidy, newly swept, pots hung at even intervals from hooks on the walls. The hearth took up a whole end of the room, so big all of her family and the Tourniers could stand in it together – all of her family before she began to lose them. Her sister, dead. Her mother, dead. Her brothers, soldiers. Just she and her father now.

—La Rousse.

She turned round, saw Etienne’s eyes, the swagger in his stride, and backed up until granite touched her back. He matched her step and put his hands on her hips.

—Not here, she said. Not in your parents’ house, on the hearth. If your mother—

Etienne dropped his hands. The mention of his mother was enough to tame him.

—Have you asked them?

He was silent. His broad shoulders sagged and he stared off into a corner.

—You have not asked them.

—I’ll be twenty-five soon and I can do what I want then. I won’t need their permission then.

Of course they don’t want us to marry, Isabelle thought. My family is poor, we have nothing, but they are rich, they have a Bible, a horse, they can write. They marry their cousins, they are friends with Monsieur Marcel. Jean Tournier is the Duc de l’Aigle’s syndic, collecting tax from us. They would never accept as their daughter a girl they call La Rousse.

—We could live with my father, she suggested. It has been hard for him without my brothers. He needs—

—Never.

—So we must live here.

—Yes.

—Without their consent.

Etienne shifted his weight from one leg to the other, leaned against the edge of the table, crossed his arms. He looked at her directly.

—If they don’t like you, he said softly, it’s your own fault, La Rousse.

Isabelle’s arms stiffened, her hands curled into fists.

—I have done nothing wrong! she cried. I believe in the Truth.

He smiled.

—But you love the Virgin, yes?

She bowed her head, fists still clenched.

—And your mother was a witch.

—What did you say? she whispered.

—That wolf that bit your mother, he was sent by the devil to bring her to him. And all those babies dying.

She glared at him.

—You think my mother made her own daughter die? Her own granddaughter die?

—When you are my wife, he said, you will not be a midwife. He took her hand and pulled her towards the barn, away from his parents’ hearth.

—Why do you want me? she asked in a low voice he could not hear. She answered herself: Because I am the one his mother hates most.

The kestrel hovered directly overhead, fluttering against the wind. Grey: male. Isabelle narrowed her eyes. No. Reddish-brown, the colour of her hair: female.

Alone she had learned to remain on the surface of the water, lying on her back, arms stroking out from her sides, breasts flattened, hair floating in the river like leaves around her face. She looked up again. The kestrel was diving to her right. The brief moment of impact was hidden by a clump of broom. When the bird reappeared it was carrying a tiny creature, a mouse or a sparrow. It flew up fast then and out of sight.

She sat up abruptly, crouching on the long smooth rock of the river bed, her breasts regaining their roundness. The sounds arose out of nothing, a tinkle here and there, then suddenly joined together into a chorus of hundreds of bells. The estiver – Isabelle’s father had predicted they would arrive in two days’ time. Their dogs must be good this summer. If she didn’t hurry she would be surrounded by hundreds of sheep. She stood up quickly and picked her way to the bank, where she brushed the water from her skin with the flat of her hand and wrung the river from her hair. Her shameful hair. She pulled on her dress and smock and wound her hair out of sight in a long piece of white linen.

She was tucking in the end of the linen when she froze, feeling eyes on her. She searched as much of the surrounding land as she could without moving her head but could see nothing. The bells were still far away. With her fingers she felt for loose strands of hair and pushed them under the cloth, then dropped her arms, pulled her dress up away from her feet, and began to run down the path next to the river. Soon she turned off it and crossed a field of scrubby broom and heather.

She reached the crest of a hill and looked down. Far below a field rippled with sheep making their way up the mountain. Two men, one in front, one at the back, and a dog on each side were keeping the flock together. Occasionally a few strays darted to one side, to be herded quickly back into the fold. They would have been walking for five days now, all the way from Alès, but at this final summit they showed no signs of flagging. They would have the whole summer to recover.

Over the bells she could hear the whistles and shouts of the men, the sharp barks of the dogs. The man in front looked up, straight at her it seemed, and whistled shrilly. Immediately a young man appeared from behind a boulder a stone’s throw to her right. Isabelle clutched her neck. He was small and wiry, sweaty and very dark from the sun. He carried a walking stick and the leather sack of a shepherd and wore a close-fitting round cap, black curls framing the brim. When she felt his dark eyes on her she knew he had seen her in the river. He smiled at her, friendly, knowing, and for a moment Isabelle felt the touch of the river on her body. She looked down, pressed her elbows to her breasts, could not smile back.

With a leap the man started down the hill. Isabelle watched his progress until he reached the flock. Then she fled.

—There is a child here. Isabelle placed a hand on her belly and stared defiantly at Etienne.

In an instant his pale eyes darkened like the shadow of a cloud crossing a field. He looked at her hard, calculating.

—I will tell my father, then we must tell your parents. She swallowed. What will they say?

—They’ll let us marry now. It would look worse if they said no when there is a child.

—They’ll think I did it deliberately.

—Did you? His eyes met hers. They were cold now.

—It was you who wanted the Sin, Etienne.

—Ah, but you wanted it too, La Rousse.

—I wish Maman were here, she said softly. I wish Marie were here.

Her father acted as if he had not heard her. He sat on the bench by the door and scraped at a branch with his knife; he was making a new pole for the hoe he had broken earlier that day. Isabelle stood motionless in front of him. She had said it so quietly that she began to think she would have to repeat herself. She opened her mouth to speak when he said:— You have all left me.

—I’m sorry, Papa. He says he won’t live here.

—I wouldn’t have a Tournier in my house. This farm won’t go to you when I die. You’ll get your dowry, but I will leave the farm to my nephews over at l’Hôpital. A Tournier will never get my land.

—The twins will return from the wars, she suggested, fighting tears.

—No. They will die. They’re not soldiers, but farmers. You know that. Two years and no word from them. Plenty have passed through from the north and no news.

Isabelle left her father sitting on the bench and walked across their fields, along the river, down to the Tournier farm. It was late, more dark than light, long shadows cast along the hills and the terraced fields full of half-grown rye. A flock of starlings sang in the trees. The route between the two farms seemed long now, at the end of it Etienne’s mother. Isabelle began walking more slowly.

She had reached the Tourniers’ empty cleda, the season’s chestnuts long since dried, when she saw the grey shadow emerge skittishly from the trees to stand in the path.

—Sainte Vierge, aide-moi, she prayed automatically. She watched the wolf watching her, its yellow eyes bright despite the gloom. When it began to move towards her, Isabelle heard a voice in her head:— Don’t let this happen to you too.

She crouched and picked up a large branch. The wolf stopped. She stood up and advanced, waving the stick and shouting. The wolf began to move backwards, and when Isabelle pretended to throw the branch, it turned and skittered sideways, disappearing into the trees.

Isabelle ran from the woods and across a field, rye cutting into her calves. She reached the rock shaped like a mushroom that marked the bottom of the Tourniers’ kitchen garden and stopped to catch her breath. Her fear of Etienne’s mother was gone.

—Thank you, Maman, she said softly. I won’t forget.

Jean, Hannah and Etienne were sitting by the fire while Susanne cleared the last of their bajanas, the same chestnut soup Isabelle had served her father earlier, and dark, sweet-smelling bread. All four froze when Isabelle entered.

—What is it, La Rousse? Jean Tournier asked as she stood in the middle of the room, her hand once more resting on the table as if to secure her a place among them.

Isabelle said nothing but looked steadily at Etienne. At last he stood up and moved to her side. She nodded and he turned to face his parents.

The room was silent. Hannah’s face looked like granite.

—Isabelle is going to have a child, Etienne said in a low voice. With your permission we would like to marry.

It was the first time he had ever used Isabelle’s name.

Hannah’s voice pierced.

—You carry whose child, La Rousse? Not Etienne’s.

—It is Etienne’s child.

—No!

Jean Tournier put his hands on the table and stood up. His silver hair was smooth like a cap against his skull, his face gaunt. He said nothing, but his wife stopped speaking and sat back. He looked at Etienne. There was a long pause before Etienne spoke.

—It is my child. We will marry anyway when I am twenty-five. Soon.

Jean and Hannah exchanged glances.

—What does your father say? Jean asked Isabelle.

—He has given his permission and will provide the dowry. She said nothing about his hatred.

—Go and wait outside, La Rousse, Jean said quietly. You go with her, Susanne.

The girls sat side by side on the door bench. They had seen little of each other since they were children. Many years ago, even before Isabelle’s hair turned red, Susanne had played with Marie, helping with the haying, the goats, splashing in the river.

For a while they sat, looking out over the valley.

—I saw a wolf out by the cleda, Isabelle said suddenly.

Susanne stared, brown eyes wide. She had the thin face and pointed chin of her father.

—What did you do?

—Chased it with a stick. She smiled, pleased with herself.

—Isabelle—

—What is it?

—I know Maman is upset, but I am glad you will live with us. I never believed what they said about you, about your hair and— She stopped. Isabelle did not ask.

—And you will be safe here. This house is safe, protected by—

She stopped again, glanced at the door, bowed her head. Isabelle let her eyes rest on the shadowy humps of the hills in the distance.

It will always be like this, she thought. Silence in this house.

The door opened and Jean and Etienne emerged with a flickering torch and an axe.

—We will take you back, La Rousse, Jean said. I must speak with your father.

He handed a piece of bread to Etienne.

—Take this bread together and give her your hand.

Etienne tore the bread in two and gave the smaller piece to Isabelle. She put it in her mouth and placed her hand in his. His fingers were cold. The bread stuck in the back of her throat like a whisper.

Petit Jean was born in blood and was a fearless child.

Jacob was born blue. He was a quiet child: even when Hannah smacked his back to start his breath he did not scream.

Isabelle lay in the river again, many summers later. There were marks on her body from the two boys, and another child pushing her belly above the water. The baby kicked. She cupped the mound with her hands.

—Please let the Virgin make it a girl, she prayed. And when she is born I will name her after you, after my sister. Marie. I will fight everyone to name her that.

This time there were no warnings at all, no bells, no sense of eyes on her. He was just there, sitting on his heels on the river bank. She sat up and looked at him. She did not cover her breasts. He looked the same, a little older, with a long scar down the right side of his face, from his cheekbone to his chin, touching the corner of his mouth. This time she would have smiled back at him if he had smiled. The shepherd did not smile. He simply nodded at her, cupped his hands, splashed water on his face, then turned and walked in the direction of the river’s source.

Marie was born in a flood of clear liquid, her eyes open. She was a hopeful child.