Читать книгу The Virgin Blue - Tracy Chevalier - Страница 8

Оглавление

When Rick and I moved to France, I figured my life would change a little. I just didn’t know how.

To begin with, the new country was a banquet where we were ready to try every dish. Our first week there, while Rick was sharpening his pencils at his new office, I knocked the rust from my high-school French and set out to explore the countryside surrounding Toulouse and to find us a place to live. A small town was what we wanted; an interesting town. I sped along little roads in a new grey Renault, driving fast through long lines of sycamores. Occasionally when I wasn’t paying attention I thought I was in Ohio or Indiana, but the landscape snapped back into itself the moment I saw a house with a red tile roof, green shutters, window boxes full of geraniums. Everywhere farmers in bright blue work pants stood in fields dusted with pale April green and watched my car pass across their horizon. I smiled and waved; sometimes they waved back, hesitantly. ‘Who was that?’ they were probably asking themselves.

I saw a lot of towns and rejected them all, sometimes for frivolous reasons, but ultimately because I was looking for a place that would sing to me, that would tell me my search was over.

I arrived in Lisle-sur-Tarn by crossing a long narrow bridge over the River Tarn. At the end of it a church and a café marked the town’s edge. I parked next to the café and began to walk; by the time I reached the centre of town I knew we would live there. It was a bastide, a fortified town preserved from the Middle Ages; when there were invasions in medieval times the villagers would gather in the market square and close off its four entrances. I stood in the middle of the square next to a fountain with lavender bushes planted around it and felt contained and content.

The square was surrounded on all four sides by an arched, covered walkway, with shops on the ground level and shuttered houses above. The arches were built of long narrow bricks; the same bricks made up the top two levels of the houses, laid horizontally or diagonally in decorative patterns between brown timbers, held together with dull pink mortar.

This is what I need, I thought. Seeing this every day will make me happy.

Immediately I began having doubts. It seemed absurd to decide on a town because of one beautiful square. I began to walk again, looking for that deciding factor, the sign that would make me stay or go.

It didn’t take long. After exploring the surrounding streets I entered a boulangerie on the square. The woman behind the counter was short and wore a navy blue and white housecoat I’d seen for sale at every market I had visited. When she finished with another customer she turned to me, black eyes scrutinizing me from a lined face, hair pulled back in a loose bun.

‘Bonjour, Madame,’ she said in the singsong intonation French women use in shops.

‘Bonjour,’ I replied, glancing at the bread on the shelves behind her and thinking: This will be my boulangerie now. But when I looked back at her, expecting a warm welcome, my confidence fell away. She stood solidly behind the counter, her face like armour.

I opened my mouth: nothing came out. I swallowed. She stared at me and said, ‘Oui, Madame?’ in exactly the same tone she’d first used, as if the last few awkward seconds hadn’t occurred.

I hesitated, then pointed at a baguette. ‘Un,’ I managed to say, though it sounded more like a grunt. The woman’s face modulated into the stiffness of disapproval. She reached behind her without looking, eyes still fixed on me.

‘Quelque chose d’autre, Madame?’

For a moment I stepped outside myself and saw myself as she must see me: foreign, transient, thick tongue stumbling over peculiar sounds, dependent on a map to locate me in a strange landscape and a phrasebook and dictionary to communicate. She made me feel lost the very moment I thought I’d found home.

I looked at the display, desperate to show her I wasn’t as ridiculous as I seemed. I pointed at some onion quiches and managed to say, ‘Et un quiche.’ A split second afterwards I knew I’d used the wrong article – quiche was feminine and should be used with une – and groaned inwardly.

She put one in a small bag and laid it on the counter next to the baguette. ‘Quelque chose d’autre, Madame?’ she repeated.

‘Non.’

She rang up the purchases on the cash register. Mutely I handed her the money, then realized when she placed my change on a small tray on the counter that I should have put the money there rather than directly into her hand. I frowned. It was a lesson I ought to have learned already.

‘Merci, Madame,’ she intoned with a blank face and flinty eyes.

‘Merci,’ I mumbled.

‘Au revoir, Madame.’

I turned to go, then stopped, thinking there must be a way to salvage this. I looked at her: she had crossed her arms over her vast bosom.

‘Je – nous – nous habitons près d’ici, là-bas,’ I lied, gesturing wildly behind me, clawing out a territory somewhere in her town.

She nodded once. ‘Oui, Madame. Au revoir, Madame.’

‘Au revoir, Madame,’ I replied, spinning around and out the door.

Oh Ella, I thought as I trudged across the square, what are you doing, lying to save face?

‘So don’t lie, then. Live here. Confront Madame every day over the croissants,’ I muttered in reply. I found myself by the fountain and reached over to a lavender bush, pulled off a few leaves and crushed them between my fingers. The sharp woody scent said: Reste.

Rick loved Lisle-sur-Tarn when he saw it, and made me feel better about my choice by kissing me and spinning me around in his arms. ‘Hah!’ he shouted at the old houses.

‘Shh, Rick,’ I said. It was market day in the square and I could feel all eyes on us. ‘Put me down,’ I hissed.

He just smiled and held me more tightly.

‘This is my kind of town,’ he said. ‘Just look at the detail in that brickwork!’

We wandered all over, picking out our favourite houses. Later we stopped at the boulangerie for more onion quiches. I turned red the moment Madame looked at me, but she directed most of her remarks at Rick, who found her hilarious and chuckled at her without appearing to offend her in the slightest. I could see she found him handsome: his blond ponytail in this land of short dark hair was a novelty and his Californian tan hadn’t faded yet. To me she was polite, but I detected an underlying hostility that made me tense.

‘It’s a shame those quiches are so good,’ I remarked to Rick out on the street. ‘Otherwise I’d never go in there again.’

‘Oh babe, there you go, taking things to heart. Don’t go all East-coast paranoid on me, now.’

‘She just makes me feel unwelcome.’

‘Bad customer relations. Tut-tut! Better get a personnel consultant in to sort her out.’

I grinned at him. ‘Yeah, I’d like to see her file.’

‘Positively riddled with complaints. She’s on her last legs, it’s obvious. Have a little pity on the old thing.’

It was tempting to live in one of the old houses in or near the square, but when we found out none were for rent I was secretly relieved: they were serious houses, for established members of town. Instead we found a place a few minutes’ walk from the centre, still old but without the fancy brickwork, with thick walls and tiled floors and a small back patio sheltered by a vine-covered trellis. There was no front yard: the front door opened directly onto the narrow street. The house was dark inside, though Rick reminded me that it would be cool during the summer. All of the houses we’d seen were like that. I fought against the dimness by keeping the shutters open, and caught my neighbours peeking through the windows several times before they learned not to look.

One day I decided to surprise Rick: when he came home from work that night I’d painted over the dull brown of the shutters with a rich burgundy and hung boxes of geraniums from the windows. He stood in front of the house smiling up at me as I leaned over the window sill, framed in pink and white and red blossoms.

‘Welcome to France,’ I said. ‘Welcome home.’

When my father found out Rick and I were going to live in France he encouraged me to write to a cousin several times removed who lived in Moutier, a small town in northwest Switzerland. Dad had visited Moutier once, long ago. ‘You’ll love it, I promise,’ he kept saying when he called to give me the address.

‘Dad, France and Switzerland are two different countries! I probably won’t get anywhere near Switzerland.’

‘Sure, kid, but it’s always good to have family nearby.’

‘Nearby? Moutier must be 400, 500 miles from where we’ll be.’

‘You see? Just a day’s drive. And that’s a lot closer than I’ll be to you.’

‘Dad—’

‘Just take the address, Ella. Humour me.’

How could I say no? I wrote down the address and laughed. ‘This is silly. What do I write to him: “Hello, I’m a distant cousin you’ve never heard of before and I’m on the Continent, so let’s meet up”?’

‘Why not? Listen, as an opening you could ask him about the family history, where we come from, what our family did. Use some of that time you’ll have on your hands.’

Dad was driven by the Protestant work ethic, and the prospect of me not having a job made him nervous. He kept making suggestions about useful things I could do. His anxiety fuelled my own: I wasn’t used to having free time – I’d always been busy either training or working long hours. Having time on my hands took some getting used to; I went through a phase of sleeping late and moping around the house before I devised three projects to keep me occupied.

I started by working on my dormant French, taking lessons twice a week in Toulouse with Madame Sentier, an older woman with bright eyes and a narrow face like a bird. She had a beautiful accent, and the first thing she did was to tackle mine. She hated sloppy pronunciation, and yelled at me when I began saying Oui in that throwaway manner many French have of barely moving their lips and letting the sound come out like a duck quacking. She made me pronounce it precisely, sounding all three letters, whistling the air through my teeth at the end. She was adamant that how I said things was more important than what I said. I tried to argue against her priorities, but I was no match for her.

‘If you do not pronounce the words well, no one will understand what you say,’ she declared. ‘Moreover, they will know that you are foreign and will not listen to you. The French are like that.’

I refrained from pointing out that she was French too. Anyway I liked her, liked her opinions and her firm hand, so I did her mouth exercises, pulling my lips around like they were made of bubblegum.

She encouraged me to talk as much as possible, wherever I was. ‘If you think of something, say it!’ she cried. ‘No matter what it is, however small, say it. Talk to everyone.’ Sometimes she made me talk non-stop for a set period of time, starting with one minute and working up to five minutes. I found it exhausting and impossible.

‘You are thinking a thought in English and then translating it word by word into French,’ Madame Sentier pointed out. ‘Language does not work like that. It has a grand shape. What you must do is to think in French. There should be no English in your head. Think as much as you can in French. If you cannot think in paragraphs, think in sentences, at least in words. Build it up into grand thoughts!’ She gestured, taking in the whole room and all of human intellect.

She was delighted to find out that I had Swiss relations; it was she who made me sit down and write. ‘They may have been from France originally, you know,’ she said. ‘It would be good for you to find out about your French ancestors. You will feel more connected to this country and its people. Then it will not be so hard to think in French.’

I shrugged inwardly. Genealogy was one of those middle-aged things I lumped together with all-talk radio stations, knitting and staying in on Saturday nights: I knew I would eventually indulge in all of them, but I was in no hurry about it. My ancestors didn’t have anything to do with my life right now. But to humour Madame Sentier, as part of my homework I pieced together a few sentences asking my cousin about the history of the family. When she’d checked it for grammar and spelling I sent the letter off to Switzerland.

The French lessons in turn helped me with my second project. ‘What a wonderful profession for a woman!’ Madame Sentier crowed when she heard I was studying to qualify as a midwife in France. ‘What noble work!’ I liked her too much to be annoyed by her romantic notions, so I didn’t mention the suspicion my colleagues and I were treated with by doctors, hospitals, insurance companies, even pregnant women. Nor did I bring up the sleepless nights, the blood, the trauma when something went wrong. Because it was a good job, and I hoped to be able to practise in France once I’d taken the required classes and exams.

The final project had an uncertain future, but it would certainly keep me busy when the time came. No one would have been surprised by it: I was twenty-eight, Rick and I had been married two years, and the pressure from everyone, ourselves included, was beginning to mount.

One night when we had lived in Lisle-sur-Tarn just a few weeks we went out to dinner at the one good restaurant in town. We talked idly – about Rick’s work, my day – through the crudités, the pâté, trout from the Tarn and filet mignon. When the waiter brought Rick’s crème brûlée and my tarte au citron I decided this was the moment to speak. I bit into the lemon slice garnish; my mouth puckered.

‘Rick,’ I began, setting down my fork.

‘Great brûlée,’ he said. ‘Especially the brûléed part. Here, try some.’

‘No thanks. Look, I’ve been thinking about things.’

‘Ah, is this gonna be serious talk?’

At that moment a couple entered the restaurant and were seated at the table next to us. The woman’s belly was just visible against her elegant black dress. Five months pregnant, I thought automatically, and carrying it very high.

I lowered my voice. ‘You know how every now and then we talk about having kids?’

‘You want to have kids now?’

‘Well, I was thinking about it.’

‘OK.’

‘OK what?’

‘OK let’s do it.’

‘Just like that? “Let’s do it”?’

‘Why not? We know we want them. Why agonize over it?’

I felt let down, though I knew Rick too well to be surprised by his attitude. He always made decisions quickly, even big ones, whereas I wanted the decisions to be more complicated.

‘I feel—’ I considered how to explain it. ‘It’s kind of like a parachute jump. Remember when we did that last year? You’re up in this tiny plane and you keep thinking, Two minutes till I can’t say no anymore, One minute till I can’t turn back, then, Here I am balancing by the door, but I can still say no. And then you jump and you can’t get back in, no matter how you feel about the experience. That’s how I feel now. I’m standing by the open door of the plane.’

‘I just remember that fantastic sensation of falling. And the beautiful view floating down. It was so quiet up there.’

I sucked at the inside of my cheek, then took a big bite of tart.

‘It’s a big decision,’ I said with my mouth full.

‘A big decision made.’ Rick leaned over and kissed me. ‘Mmm, nice lemon.’

Later that night I slipped out of the house and went to the bridge. I could hear the river far below but it was too dark to see the water. I looked around; with no one in sight I pulled out a pack of contraceptive pills and began to push the tablets one by one out of their metal foil. They disappeared toward the water, tiny white flashes pinpointed in the dark for a second. After they were gone I leaned against the railing for a long time, willing myself to feel different.

Something did change that night. That night I had the dream for the first time. It began with flickering, a movement between dark and light. It wasn’t black, it wasn’t white; it was blue. I was dreaming in blue.

It moved like it was being buffeted by the wind, undulating toward me and away. It began to press into me, the pressure of water rather than stone. I could hear a voice chanting. Then I was reciting too, the words pouring from me. The other voice began to cry; then I was sobbing. I cried until I couldn’t breathe. The pressure of the blue closed in around me. There was a great boom, like the sound of a heavy door falling into place, and the blue was replaced by a black so complete it had never known light.

Friends had told me that when you try to conceive, you have either lots more sex or lots less. You can go at it all the time, the way a shotgun sprays its pellets everywhere in the hope of hitting something. Or you can strike strategically, saving your ammunition for the appropriate moment.

To start with, Rick and I went for the first approach. When he got home from work we made love before dinner. We went to bed early, woke up early to do it, fit it in whenever we could.

Rick loved this abundance, but for me it was different. For one thing, I’d never had sex because I felt I had to – it had always been because I wanted to. Now, though, there was an unspoken mission behind the activity that made it feel deliberate and calculated. I was also ambivalent about not using contraception: all the energy I’d put into prevention over the years, all the lessons and caution drilled into me – were they to be tossed away in a moment? I’d heard that this could be a great turn-on, but I felt fear when I’d expected exhilaration.

Above all, I was exhausted. I was sleeping badly, dragged into a room of blue each night. I didn’t say anything to Rick, never woke him or explained the next day why I was so tired. Usually I told him everything; now there was a block in my throat and a lock on my lips.

One night I was lying in bed, staring at the blue dancing above me, when it finally dawned on me: the only two nights I hadn’t had the dream in the last ten days were when we hadn’t had sex.

Part of me was relieved to make that connection, to be able to explain it: I was anxious about conceiving, and that was bringing on the nightmare. Knowing that made it a little less frightening.

Still, I needed sleep; I had to convince Rick to cut down on sex without explaining why. I couldn’t bring myself to tell him I had nightmares after he made love to me.

Instead, when my period came and it was clear we hadn’t conceived, I suggested to Rick that we try the strategic approach. I used every textbook argument I knew, threw in some technical words and tried to be cheerful. He was disappointed but gave in gracefully.

‘You know more about this than me,’ he said. ‘I’m just the hired gun. You tell me what to do.’

Unfortunately, though the dream came less frequently, the damage had been done: I found it harder to sleep deeply, and often lay awake in a state of non-specific anxiety, waiting for the blue, thinking that some night it would return anyway, unaccompanied by sex.

One night – a strategic night – Rick was kissing his way from my shoulder down my arm when he paused. I could feel his lips hovering above the crease in my arm. I waited but he didn’t continue. ‘Um, Ella,’ he said at last. I opened my eyes. He was staring at the crease; as my eyes followed his gaze my arm jerked away from him.

‘Oh,’ I said simply. I studied the circle of red, scaly skin.

‘What is it?’

‘Psoriasis. I had it once, when I was thirteen. When Mom and Dad divorced.’

Rick looked at it, then leaned over and kissed my eyelids shut.

When I opened my eyes again I just caught a flicker of distaste cross his face before he controlled himself and smiled at me.

Over the next week I watched helplessly as the original patch widened, then jumped to my other arm and both elbows. It would reach my ankles and calves soon.

At Rick’s insistence I went to see a doctor. He was young and brusque, lacking the patter American doctors use to soften up their patients. I had to concentrate hard on his rapid French.

‘You have had this before?’ he asked as he studied my arms.

‘Yes, when I was young.’

‘But not since?’

‘No.’

‘How long have you been in France?’

‘Six weeks.’

‘And you will stay?’

‘Yes, for a few years. My husband has a job with an architectural firm in Toulouse.’

‘You have children?’

‘No. Not yet.’ I turned red. Pull yourself together, Ella, I thought. You’re twenty-eight years old, you don’t have to be embarrassed about sex anymore.

‘And you work now?’

‘No. That is, I did, in the United States. I was a midwife.’

He raised his eyebrows. ‘Une sage-femme? Do you want to practise in France?’

‘I would like to work but I haven’t been able to get a work permit yet. Also the medical system is different here, so I have to pass an exam before I can practise. So now I study French and this autumn I begin a course for midwives in Toulouse to study for the exam.’

‘You look tired.’ He changed the subject abruptly, as if to suggest I was wasting his time by talking about my career.

‘I’ve been having nightmares, but—’ I stopped. I didn’t want to get into this with him.

‘You are unhappy, Madame Turner?’ he asked more gently.

‘No, no, not unhappy,’ I replied uncertainly. Sometimes it’s hard to tell when I’m so tired, I added to myself.

‘You know psoriasis appears sometimes when you do not get enough sleep.’

I nodded. So much for psychological analysis.

The doctor prescribed cortisone cream, suppositories to bring down the swelling and sleeping pills in case the itching kept me awake, then told me to come back in a month. As I was leaving he added, ‘And come to see me when you are pregnant. I am also an obstétricien.’

I blushed again.

My infatuation with Lisle-sur-Tarn ended not long after I stopped sleeping.

It was a beautiful, peaceful town, moving at a pace I knew was healthier than what I’d been used to in the States, and the quality of life was undeniably better. The produce at the Saturday market in the square, the meat at the boucherie, the bread at the boulangerie – all tasted wonderful to someone brought up on bland supermarket products. In Lisle lunch was still the biggest meal of the day, children ran freely with no fear of strangers or cars, and there was time for small talk. People were never in too much of a hurry to stop and chat with everyone.

With everyone but me, that is. As far as I knew, Rick and I were the only foreigners in town. We were treated that way. Conversations stopped when I entered stores, and when resumed I was sure the subject had been changed to something innocuous. People were polite to me, but after several weeks I still felt I hadn’t had a real conversation with anyone. I made a point of saying hello to people I recognized, and they said hello back, but no one said hello to me first or stopped to talk to me. I tried to follow Madame Sentier’s advice about talking as much as I could, but I was given so little encouragement that my thoughts dried up. Only when a transaction took place, when I was buying things or asking where something was, did the townspeople spare a few words for me.

One morning I was sitting in a café on the square, drinking coffee and reading the paper. Several other people were scattered among the tables. The proprietor passed among us, chatting and joking, handing out candy to the children. I had been there a few times; he and I were on nodding terms now but had not progressed to conversation. Give that about ten years, I thought sourly.

A few tables away, a woman younger than me sat with a five-month-old baby who was strapped into a car seat set on a chair, shaking a rattle. The woman wore tight jeans and had an irritating laugh. She soon got up and went inside. The baby didn’t seem to notice she’d gone.

I concentrated on Le Monde. I was forcing myself to read the entire front page before I was allowed to touch the International Herald Tribune. It was like wading through mud: not just because of the language, but also all the names I didn’t recognize, the political situations I knew nothing about. Even when I understood a story I wasn’t necessarily interested in it.

I was ploughing through a piece about an imminent postal strike – a phenomenon I wasn’t accustomed to in the States – when I heard a strange noise, or rather, silence. I looked up. The baby had stopped shaking the rattle and let it drop into his lap. His face began to crumple like a napkin being scrunched after a meal. Right, here comes the crying, I thought. I glanced into the café: his mother was leaning against the bar, talking on the phone and playing idly with a coaster.

The baby didn’t cry: his face grew redder and redder, as if he were trying to but couldn’t. Then he turned purple and blue in quick succession.

I jumped up, my chair falling backwards with a bang. ‘He’s choking!’ I shouted.

I was only ten feet away but by the time I reached him a ring of customers had formed around him. A man was crouched in front of the baby, patting his blue cheeks. I tried to squeeze through but the proprietor, his back to me, kept stepping in front of me.

‘Hang on, he’s choking!’ I cried. I was facing a wall of shoulders. I ran to the other side of the circle. ‘I can help him!’

The people I was pushing between looked at me, their faces hard and cold.

‘You have to pound him on the back, he’s not getting any air.’

I stopped. I had been speaking in English.

The mother appeared, melting through the barricade of people. She began frantically hitting the baby’s back, too hard, I thought. Everyone stood watching her in an eerie silence. I was wondering how to say ‘Heimlich manoeuvre’ in French when the baby suddenly coughed and a red candy lozenge shot out of his mouth. He gasped for air, then began to cry, his face going bright red again.

There was a collective sigh and the ring of people broke up. I caught the proprietor’s eye; he looked at me coolly. I opened my mouth to say something, but he turned away, picked up his tray and went inside. I gathered up my newspapers and left without paying.

After that I felt uncomfortable in town. I avoided the café and the woman with her baby. I found it hard to look people in the eye. My French became less confident and my accent deteriorated.

Madame Sentier noticed immediately. ‘But what has happened?’ she asked. ‘You were progressing so well!’

An image of a ring of shoulders came to mind. I said nothing.

One day at the boulangerie I heard the woman ahead of me say she was on her way to ‘la bibliothèque’, gesturing as if it were just around the corner. Madame handed her a plastic-covered book; it was a cheap romance. I bought my baguettes and quiches in a rush, cutting short my awkward ritual conversation with Madame. I ducked out and trailed the other woman as she made her daily purchases around the square. She stopped to say hello to several people and argued with all the storekeepers while I sat on a bench in the square and kept an eye on her over my newspaper. She made stops on three sides of the square before abruptly entering the town hall on the last side. I folded my paper and raced after her, then found myself having to hover in the lobby examining wedding banns and planning permission notices while she laboured up a long flight of stairs. I took the stairs two at a time and slipped through the door after her. Shutting it behind me, I turned to face the first place in town that felt familiar.

The library had exactly that mixture of seediness and comforting quiet that made me love public libraries back home. Though it was small – only two rooms – it had high ceilings and several unshuttered windows, giving it an unusually airy feel for such an old building. Several people looked up from what they were doing to stare at me, but their attention was mercifully short and one by one they went back to reading or talking together in low voices.

I had a look around and then went to the main desk to apply for a library card. A pleasant, middle-aged woman in a smart olive suit told me I would need to bring in something with my French address on it as proof of residence. She also tactfully pointed me in the direction of a multi-volume French-English dictionary and a small English-language section.

The woman wasn’t behind the desk the second time I visited the library; in her place a man stood talking on the phone, his sharp brown eyes focused on a point out in the square, a sardonic smile on his angular face. About my height, he was wearing black trousers and a white shirt without a tie, buttoned at the collar, sleeves rolled up above his elbows. A lone wolf. I smiled to myself: one to avoid.

I veered away from him and headed for the English-language section. It looked like some tourists had donated a sackful of vacation reading: it was full of thrillers and sex-and-shopping novels. There was also a good selection of Agatha Christie. I found one I hadn’t read, then browsed in the French fiction section. Madame Sentier had recommended Françoise Sagan as a painless way to ease myself into reading in French; I chose Bonjour Tristesse. I started toward the front desk, glanced at the wolf behind it, then at my two frivolous books, and stopped. I went back to the English section, dug around and added Portrait of a Lady to my pile.

I dawdled for a while, poring over a copy of Paris Match. Finally I carried my books up to the desk. The man behind it looked hard at me, made some mental calculation as he glanced at the books and, with the faintest smirk, said in English, ‘Your card?’

Damn you, I thought. I hated that sneering appraisal, the assumption that I couldn’t speak French, that I looked so American.

‘I would like to apply for a card,’ I replied carefully in French, trying to pronounce the words without any trace of an American accent.

He handed me a form. ‘Fill out this,’ he commanded in English.

I was so annoyed that when I filled in the application I wrote down my last name as Tournier rather than Turner. I pushed the sheet defiantly toward him along with driver’s licence, credit card and a letter from the bank with our French address on it. He glanced at the pieces of identification, then frowned at the sheet.

‘What is this “Tournier”?’ he asked, tapping his finger on my name. ‘It is Turner, yes? Like Tina Turner?’

I continued to answer in French. ‘Yes, but my family name was originally Tournier. They changed it when they moved to the United States. In the nineteenth century. They took out the “o” and the “i” so that the name would be more American.’ This was the one bit of family lore I knew and I was proud of it, but it was clear he wasn’t impressed. ‘Lots of families changed their names when they emigrated—’ I trailed off and looked away from his mocking eyes.

‘Your name is Turner, so there must be Turner on the card, yes?’

I lapsed into English. ‘I – since I’m living here now I thought I’d start using Tournier.’

‘But you have no card or letter with Tournier on it, no?’

I shook my head and scowled at the stack of books, elbows clenched to my sides. To my mortification my eyes began to fill with tears. ‘Never mind, it’s nothing,’ I muttered. Careful not to look at him, I scooped up the cards and letter, turned around and pushed my way out.

That night I opened the front door of our house to shoo away two cats fighting in the street and stumbled over the stack of books on the front step. The library card was sitting on top and was made out to Ella Tournier.

I stayed away from the library, stifling my urge to make a special trip to thank the librarian. I hadn’t yet learned how to thank French people. When I was buying something they seemed to thank me too many times during the exchange, yet I always doubted their sincerity. It was hard to analyse the tone of their words. But the librarian’s sarcasm had been undeniable; I couldn’t imagine him accepting thanks with grace.

A few days after the card appeared I was walking along the road by the river and saw him sitting in a patch of sunlight in front of the café by the bridge, where I’d begun going for coffee. He seemed mesmerized by the water far below and I stopped, trying to decide whether or not to say something to him, wondering if I could pass by quietly so he wouldn’t notice. He glanced up then and caught me watching him. His expression didn’t change; he looked as if his thoughts were far away.

‘Bonjour,’ I said, feeling foolish.

‘Bonjour.’ He shifted slightly in his seat and gestured to the chair next to him. ‘Café?’

I hesitated. ‘Oui, s’il vous plaît,’ I said at last. I sat down and he nodded at the waiter. For a moment I felt acutely embarrassed and cast my eyes out over the Tarn so I wouldn’t have to look at him. It was a big river, about 100 yards wide, green and placid and seemingly still. But as I watched I noticed there was a slow roll to the water; I kept my eyes on it and saw occasional flashes of a dark, rust-red substance boiling to the surface and then disappearing again. Fascinated, I followed the red patches with my eyes.

The waiter arrived with the coffee on a silver tray, blocking my view of the river. I turned to the librarian. ‘That red there in the Tarn, what is it?’ I asked in French.

He answered in English. ‘Clay deposits from the hills. There was a landslide recently that exposed the clay under the soil. It washes down into the river.’

My eyes were drawn back to the water. Still watching the clay I switched to English. ‘What’s your name?’

‘Jean-Paul.’

‘Thank you for the library card, Jean-Paul. That was very nice of you.’

He shrugged and I was glad I hadn’t made a bigger deal of it.

We sat without speaking for a long time, drinking our coffee and looking at the river. It was warm in the late May sun and I would have taken off my jacket but I didn’t want him to see the psoriasis on my arms.

‘Why aren’t you at the library?’ I asked abruptly.

He looked up. ‘It’s Wednesday. Library’s closed.’

‘Ah. How long have you worked there?’

‘Three years. Before that I was at a library in Nîmes.’

‘So that’s your career? You’re a librarian?’

He gave me a sideways look as he lit a cigarette. ‘Yes. Why do you ask?’

‘It’s just – you don’t seem like a librarian.’

‘What do I seem like?’

I looked him over. He was wearing black jeans and a soft salmon-coloured cotton shirt; a black blazer was draped over the back of his chair. His arms were tanned, the forearms densely covered with black hair.

‘A gangster,’ I replied. ‘Except you need sunglasses.’

Jean-Paul smiled slightly and let smoke trickle from his mouth so that it formed a blue curtain around his face. ‘What is it you Americans say? “Don’t judge a book by its cover”.’

I smiled back. ‘Touché.’

‘So why are you here in France, Ella Tournier?’

‘My husband is working as an architect in Toulouse.’

‘And why are you here?’

‘We wanted to try living in a small town rather than in Toulouse. We were in San Francisco before, and I grew up in Boston, so I thought a small town would be an interesting change.’

‘I asked why are you here?’

‘Oh.’ I paused. ‘Because my husband is here.’

He raised his eyebrows and stubbed out his cigarette.

‘I mean, I wanted to come. I was glad for the change.’

‘You were glad or you are glad?’

I snorted. ‘Your English is very good. Where did you learn it?’

‘I lived in New York for two years. I was studying for a library science degree at Columbia University.’

‘You lived in New York and then came back here?’

‘To Nîmes and then here, yes.’ He gave me a little smile. ‘Why is that so surprising, Ella Tournier? This is my home.’

I wished he would stop using Tournier. He was looking at me with the smirk I’d first seen on his face at the library, impenetrable and condescending. I would’ve liked to see his face as he wrote out my library card: had he made that into a superior act as well?

I stood up abruptly and fumbled in my purse for some coins. ‘It’s been nice talking, but I have to go.’ I laid the money on the table. Jean-Paul looked at it and frowned, shaking his head almost imperceptibly. I turned red, scraped the coins up and turned to go.

‘Au revoir, Ella Tournier. Enjoy the Henry James.’

I spun round. ‘Why do you keep using my last name like that?’

He leaned back, the sun in his eyes so that I couldn’t see his expression. ‘So you will grow accustomed to it. Then it will become your name.’

Delayed by the postal strike, my cousin’s reply arrived on June 1st, about a month after I’d written to him. Jacob Tournier had written two pages of large, almost indecipherable scrawl. I got out my dictionary and began to work through the letter, but it was so hard to read that after looking up several words without success I gave up and decided to use the bigger dictionary at the library.

Jean-Paul was talking to another man at his desk as I walked in. There was no change in his demeanour or expression but I noted with a satisfaction that surprised me that he glanced at me as I passed. I took the dictionary volumes to a desk and sat with my back to him, annoyed with myself for being so aware of him.

The library dictionary was more helpful but there were still words I couldn’t find, and more words I simply couldn’t read. After spending fifteen minutes on one paragraph, I sat back, dazed and frustrated. It was then that I saw Jean-Paul, leaning against the wall to my left and watching me with an amused expression that made me want to slap him. I jumped up and thrust the letter at him, muttering, ‘Here, you do it!’

He took the sheets, gave them a cursory glance and nodded. ‘Leave it with me,’ he said. ‘See you Wednesday at the café.’

On Wednesday morning he was sitting at the same table, in the same chair, but it was cloudy this time and there were no bubbling clay deposits in the river. I sat opposite him rather than in the adjacent seat, so that the river was at my back and we had to look at each other. Beyond him I could see into the empty café: the waiter, reading a newspaper, glanced up as I sat down and abandoned his paper when I nodded.

Neither of us said anything while we waited for our coffee. I was too tired to make small talk; it was the strategic time of the month and the dream had woken me three nights running. I hadn’t been able to get back to sleep and had lain hour after hour listening to Rick’s even breathing. I’d been resorting to cat naps in the afternoons, but they made me feel ill and disoriented. For the first time I’d begun to understand the look I had seen on the faces of new mothers I’d worked with: the bewildered, shattered expression of someone robbed of sleep.

After the coffee came Jean-Paul placed Jacob Tournier’s letter on the table. ‘There are some Swiss expressions in it,’ he said, ‘which maybe you would not understand. And the handwriting was difficult, though I have read worse.’ He handed me a neatly written page of translation,

My dear cousin,

What a pleasure to receive your letter! I remember well your father from his brief visit to Moutier long ago and am happy to make the acquaintance of his daughter.

I am sorry for the delay in my reply to your questions, but they required that I should look through my grandfather’s old notes about the Tourniers. It was he who had a great interest in the family, you see, and he undertook many researches. In fact he made a family tree – it is difficult to read or reproduce it for you in this letter, so you will have to visit us and see it.

Nonetheless I can give you some facts. The first mention of a Tournier in Moutier was of Etienne Tournier, on a military list in 1576. Then there was a baptism registered in 1590 of another Etienne Tournier, the son of Jean Tournier and Marthe Rougemont. There are few records left from that time, but later there are many mentions of Tourniers – the family tree is abundant from the eighteenth century to the present.

The Tourniers have had many occupations: tailor, innkeeper, watchmaker, schoolteacher. A Jean Tournier was even elected mayor in the early nineteenth century.

You ask about French origins. My grandfather sometimes said that the family originally came from the Cévennes. I do not know from where he had this information.

It pleases me that you have interest in the family, and I hope you and your husband will visit us sometime soon. A new member of the Tournier family is always welcome to Moutier.

Yours etc.

Jacob Tournier

I looked up. ‘Where’s Cévennes?’ I asked.

Jean-Paul gestured over my shoulder. ‘Northeast of here. It’s an area in the mountains north of Montpellier, west of the Rhône. Around the Tarn and to the south.’

I fastened on to the one familiar bit of geography. ‘This Tarn?’ I pointed with my chin at the river below, hoping he hadn’t noticed that I’d thought Cévennes was a town.

‘Yes. It’s a very different river further east, closer to its source. Much smaller, quicker.’

‘And where’s the Rhône?’

He flicked me a look, then reached into his jacket pocket for a pen, and quickly sketched the outline of France on a napkin. The shape reminded me of a cow’s head: the east and west points the ears, the top point the tuft of hair between the ears, the border with Spain the square muzzle. He drew dots for Paris, Toulouse, Lyons, Marseilles, Montpellier, squiggly vertical and horizontal lines for the Rhône and the Tarn. As an afterthought he added a dot next to the Tarn and to the right of Toulouse to mark Lisle-sur-Tarn. Then he circled part of the cow’s left cheek just above the Riviera. ‘That’s the Cévennes.’

‘You mean they were from a place nearby?’

Jean-Paul blew out his lips. ‘From here to the Cévennes is at least 200 kilometres. You think that is near?’

‘It is to an American,’ I replied defensively, well aware that I’d recently chided my father for making the same assumption. ‘Some Americans will drive 100 miles to a party. But look, it’s an amazing coincidence that in your big country—’ I gestured at the cow’s head – ‘my ancestors came from a place pretty close to where I live now.’

‘An amazing coincidence,’ Jean-Paul repeated in a way that made me wish I’d left off the adjective.

‘Maybe it wouldn’t be so hard then to find out more about them, since it’s nearby.’ I was remembering Madame Sentier saying that to know about my French ancestors would make me feel more at home. ‘I could just go there and—’ I stopped. What would I do there exactly?

‘You know your cousin said it is a family story that they came from there. So it is not certain information. Not concrete.’ He sat back, shook a cigarette out of the pack on the table and lit it in one fluid movement. ‘Besides, you already know this information about your Swiss ancestors, and there exists a family tree. They have traced the family back to 1576, more information than most people know about their families. That is enough, no?’

‘But it would be fun to dig around. Do some research. I could look up records or something.’

He looked amused. ‘What kind of records, Ella Tournier?’

‘Well, birth records. Death records. Marriages. That kind of thing.’

‘And where are you finding these records?’

I flung out my hands. ‘I don’t know. That’s your job. You’re the librarian!’

‘OK.’ Appealing to his vocation seemed to settle him; he squared himself in his chair. ‘You could start with the archives at Mende, which is the capital of Lozère, one of the départements of the Cévennes. But I think you do not understand this word “research” you are so easy to use. There are not so many records from the sixteenth century. They did not keep records then the way the government began to do after the Revolution. There were church records, yes, but many were destroyed during the religious wars. And especially the Huguenot records were not kept securely. So it is all very unusual that you find something about the Tourniers if you go to Mende.’

‘Wait a minute. How do you know they were, uh, Huguenots?’

‘Most of the French who went to Switzerland then were Huguenots looking for a safe place, or who wanted to be close to Calvin at Geneva. There were two main waves of migration, in 1572 and 1685, first after the Massacre of Saint Bartholomew, then with the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. You can read about them at the library. I won’t do all your work for you,’ he added tauntingly.

I ignored his gibe. I was beginning to like the idea of exploring a part of France where I might have ancestors. ‘So you think it’s worth me going to the archives at Mende?’ I asked, foolishly optimistic.

He blew smoke straight up into the air. ‘No.’

My disappointment must have been obvious, for Jean-Paul tapped the table impatiently and remarked, ‘Cheer up, Ella Tournier. It is not so easy, finding out about the past. You Americans who come over here looking for your roots think you will find it out all in one day, no? And then you go to the place and take a photograph and you feel good, you feel French for one day, yes? And the next day you go looking for ancestors in other countries. That way you claim the whole world for yourselves.’

I grabbed my bag and stood up. ‘You’re really enjoying this, aren’t you?’ I said sharply. ‘Thanks for your advice. I’ve really learned a lot about French optimism.’ I deliberately tossed a coin on the table; it rolled past Jean-Paul’s elbow and fell to the ground, where it bounced on the concrete a few times.

He touched my elbow as I began to walk away. ‘Wait, Ella. Don’t go. I did not know I was upsetting for you. I try just to be realistic.’

I turned on him. ‘Why should I stay? You’re arrogant and pessimistic, and you make fun of everything I do. I’m mildly curious about my French ancestors and you act like I’m tattooing the French flag on my butt. It’s hard enough living here without you making me feel even more alien.’ I turned away once more but to my surprise found I was shaking; I felt so dizzy that I had to grab onto the table.

Jean-Paul jumped up and pulled out a chair for me. As I dropped into it he called inside to the waiter, ‘Un verre d’eau, Dominique, vite, s’il te plaît.’

The water and several deep breaths helped. I fanned my face with my hands; I’d turned red and was sweating. Jean-Paul sat across from me and watched me closely.

‘Maybe you take your jacket off,’ he suggested quietly; for the first time his voice was gentle.

‘I—’ But this was not the moment for modesty and I was too tired to argue; my anger at him had faded the moment I sat back down. Reluctantly I shrugged my jacket off. ‘I’ve got psoriasis,’ I announced lightly, trying to pre-empt any awkwardness about the state of my arms. ‘The doctor says it’s from stress and lack of sleep.’

Jean-Paul looked at the patches of scaly skin like they were a curious modern painting.

‘You do not sleep?’ he asked.

‘I’ve been having nightmares. Well, a nightmare.’

‘And you tell your husband about it? Your friends?’

‘I haven’t told anyone.’

‘Why you do not talk to your husband?’

‘I don’t want him to think I’m unhappy here.’ I didn’t add that Rick might feel threatened by the dream’s connection to sex.

‘Are you unhappy?’

‘Yes,’ I said, looking straight at Jean-Paul. It was a relief to say it.

He nodded. ‘So what is the nightmare? Describe it to me.’

I looked out over the river. ‘I only remember bits of it. There’s no real story. There’s a voice – no, two voices, one speaking in French, the other crying, really hysterical crying. All of this is in a fog, like the air is very heavy, like water. And there’s a thud at the end, like a door being shut. And most of all there’s the colour blue everywhere. Everywhere. I don’t know what it is that scares me so much, but every time I have the dream I want to go home. It’s the atmosphere more than what actually happens that frightens me. And the fact that I keep having it, that it won’t go away, like it’s with me for life. That’s the worst of all.’ I stopped. I hadn’t realized how much I’d wanted to tell someone about it.

‘You want to go back to the States?’

‘Sometimes. Then I get mad at myself for being scared off by a dream.’

‘What does the blue look like? Like that?’ He pointed to a sign advertising ice cream for sale in the café. I shook my head.

‘No, that’s too bright. I mean, the dream blue is bright. Very vivid. But it’s bright and yet dark too. I don’t know the technical words to describe it. It reflects lots of light. It’s beautiful but in the dream it makes me sad. Elated too. It’s like there are two sides to the colour. Funny that I remember the colour. I always thought I dreamed in black and white.’

‘And the voices? Who are they?’

‘I don’t know. Sometimes it’s my voice. Sometimes I wake up and I’ve been saying the words. I can almost hear them, as if the room has just then gone silent.’

‘What are the words? What are you saying?’

I thought for a minute, then shook my head. ‘I don’t remember.’

He fixed his eyes on me. ‘Try. Close your eyes.’

I did as he said, sitting still as long as I could, Jean-Paul silent next to me. Just as I was about to give up, a fragment floated into my mind. ‘Je suis un pot cassé,’ I said suddenly.

I opened my eyes. ‘I am a broken pot? Where did that come from?’

Jean-Paul looked startled.

‘Can you remember any more?’

I closed my eyes again. ‘Tu es ma tour et forteresse,’ I murmured at last.

I opened my eyes. Jean-Paul’s face was screwed up in concentration and he seemed far away. I could see his mind working, travelling over a vast plain of memory, scanning and rejecting, until something clicked and he returned to me. He fixed his eyes on the ice-cream sign and began to recite:

Entre tous ceux-là qui me haient

Mes voisins j’aperçois

Avoir honte de moi:

Il semble que mes amis aient

Horreur de ma rencontre,

Quand dehors je me montre.

Je suis hors de leur souvenance,

Ainsi qu’un trespassé.

Je suis un pot cassé.

As he spoke I felt a pressure in my throat and behind my eyes. It was grief.

I held tightly to the arms of my chair, pushing my body hard against its back as if to brace myself. When he finished I swallowed to ease my throat.

‘What is it?’ I asked quietly.

‘The thirty-first psalm.’

I frowned at him. ‘A psalm? From the Bible?’

‘Yes.’

‘But how could I know it? I don’t know any psalms! Hardly in English, and certainly not in French. But those words are so familiar. I must have heard it somewhere. How do you know it?’

‘Church. When I was young we had to memorize many psalms. But also it was in my studying at one time.’

‘You studied psalms for a library science degree?’

‘No, no, before that, when I studied history. The history of the Languedoc. That is what I really do.’

‘What’s Languedoc?’

‘An area all around us. From Toulouse and the Pyrenees all the way to the Rhône.’ He drew another circle on his napkin map, encompassing the smaller circle of the Cévennes and a lot of the cow’s neck and muzzle. ‘It was named for the language once spoken there. Oc was their word for oui. Langue d’oc – language of oc.’

‘What did the psalm have to do with Languedoc?’

He hesitated. ‘Well, that’s curious. It was a psalm the Huguenots used to recite when bad things happened.’

That night after supper I finally told Rick about the dream, describing the blue, the voices, the atmosphere, as accurately as I could. I left out some things too: I didn’t tell him that I’d been over this territory with Jean-Paul, that the words were a psalm, that I only had the dream after sex. Since I had to pick and choose what I told him, the process was more self-conscious and not nearly as therapeutic as it had been with Jean-Paul, when it had come out involuntarily and naturally. Now that I was telling it for Rick’s sake rather than my own, I found I had to shape it more into a story, and it began to detach itself from me and take on its own fictional life.

Rick took it that way too. Maybe it was the way I told it, but he listened as if he were half paying attention to something else at the same time, a radio on in the background or a conversation in the street. He didn’t ask any questions the way Jean-Paul had.

‘Rick, are you listening to me?’ I asked finally, reaching over and pulling his ponytail.

‘Of course I am. You’ve been having nightmares. About the colour blue.’

‘I just wanted you to know. That’s why I’ve been so tired recently.’

‘You should wake me up when you have them.’

‘I know.’ But I knew I wouldn’t. In California I would have woken him immediately the first time I had the dream. Something had changed; since Rick seemed to be himself, it must be me.

‘How’s the studying going?’

I shrugged, irritated that he’d changed the subject. ‘OK. No. Terrible. No. I don’t know. Sometimes I wonder how I’m ever going to deliver babies in French. I couldn’t say the right thing when that baby was choking. If I can’t even do that, how can I possibly coach a woman through labour?’

‘But you delivered babies from Hispanic women back home and managed.’

‘That’s different. Maybe they didn’t speak English, but they didn’t expect me to speak Spanish either. And here all the hospital equipment, all the medicine and the dosages, all that will be in French.’

Rick leaned forward, elbows anchored on the table, plate pushed to one side. ‘Hey, Ella, what’s happened to your optimism? You’re not going to start acting French, are you? I get enough of that at work.’

Even knowing I’d just been critical of Jean-Paul’s pessimism, I found myself repeating his words. ‘I’m just trying to be realistic.’

‘Yeah, I’ve heard that at the office too.’

I opened my mouth for a sharp retort, but stopped myself. It was true that my optimism had diminished in France; maybe I was taking on the cynical nature of the people around me. Rick put a positive spin on everything; it was his positive attitude that had made him successful. That was why the French firm approached him; that was why we were here. I shut my mouth, swallowing my pessimistic words.

That night we made love, Rick carefully avoiding my psoriasis. Afterwards I lay patiently waiting for sleep and the dream. When it came it was less impressionistic, more tangible than ever. The blue hung over me like a bright sheet, billowing in and out, taking on texture and shape. I woke with tears running down my face and my voice in my ears. I lay still.

‘A dress,’ I whispered. ‘It was a dress.’

In the morning I hurried to the library. The woman was at the desk and I had to turn away to hide my disappointment and irritation that Jean-Paul wasn’t there. I wandered aimlessly around the two rooms, the librarian’s gaze following me. At last I asked her if Jean-Paul would be in any time that day. ‘Oh no,’ she replied with a small frown. ‘He won’t be here for a few days. He has gone to Paris.’

‘Paris? But why?’

She looked surprised that I should ask. ‘Well, his sister is getting married. He will return after the weekend.’

‘Oh. Merci,’ I said and left. It was strange to think of him having a sister, a family. Dammit, I thought, pounding down the stairs and out into the square. Madame from the boulangerie was standing next to the fountain talking to the woman who had first led me to the library. Both stopped talking and stared at me for a long moment before turning back to each other. Damn you, I thought. I’d never felt so isolated and conspicuous.

That Sunday we were invited to lunch at the home of one of Rick’s colleagues, the first real socializing we’d done since moving to France, not counting the occasional quick drink with people Rick had met through work. I was nervous about going and focused my worries on what to wear. I had no idea what Sunday lunch meant in French terms, whether it was formal or casual.

‘Should I wear a dress?’ I kept pestering Rick.

‘Wear what you want,’ he replied usefully. ‘They won’t mind.’

But I will, I thought, if I wear the wrong thing.

There was the added problem of my arms – it was a hot day but I couldn’t bear the furtive glances at my erupted skin. Finally I chose a stone-coloured sleeveless dress that reached my mid-calf and a white linen jacket. I thought I would fit in with more or less any occasion in such an outfit, but when the couple opened the door of their big suburban house and I took in Chantal’s jeans and white t-shirt, Olivier’s khaki shorts, I felt simultaneously overdressed and frumpy. They smiled politely at me, and smiled again at the flowers and wine we brought, but I noticed that Chantal abandoned the flowers, still wrapped, on a sideboard in the dining room, and our carefully chosen bottle of wine never made an appearance.

They had two children, a girl and a boy, who were so polite and quiet that I never even found out their names. At the end of the meal they stood up and disappeared inside as if summoned by a bell only children could hear. They were probably watching television, and I secretly wished I could join them: I found conversation among us adults tiring and at times demoralizing. Rick and Olivier spent most of the time discussing the firm’s business, and spoke in English. Chantal and I chatted awkwardly in a mixture of French and English. I tried to speak only French with her, but she kept switching to English when she felt I wasn’t keeping up. It would have been impolite for me to continue in French, so I switched to English until there was a pause; then I’d start another subject in French. It turned into a polite struggle between us; I think she took quiet pleasure in showing off how good her English was compared to my French. And she wasn’t one for small talk; within ten minutes she had covered most of the political trouble in the world and looked scornful when I didn’t have a decisive answer to every problem.

Both Olivier and Chantal hung onto every word Rick uttered, even though I made more of an effort than he did to speak to them in their own language. For all my struggle to communicate they barely listened to me. I hated comparing my performance with Rick’s: I’d never done such a thing in the States.

We left in the late afternoon, with polite kisses and promises to have them over in Lisle. That’ll be a lot of fun, I thought as we drove away. When we were out of sight I pulled off my sweaty jacket. If we had been in the States with friends it wouldn’t have mattered what my arms looked like. But then, if we were still in the States I wouldn’t have psoriasis.

‘Hey, they were nice, weren’t they?’ Rick started off our ritual debriefing.

‘They didn’t touch the wine or flowers.’

‘Yeah, but with a wine cellar like theirs, no wonder! Great place.’

‘I guess I wasn’t thinking about their material possessions.’

Rick glanced at me sideways. ‘You didn’t seem too happy there, babe. What’s wrong?’

‘I don’t know. I just feel – I just feel I don’t fit, that’s all. I can’t seem to talk to people here the way I can in the States. Until now the only person I’ve had any sustained conversation with besides Madame Sentier is Jean-Paul, and even that isn’t real conversation. More like a battle, more like—’

‘Who’s Jean-Paul?’

I tried to sound casual. ‘A librarian in Lisle. He’s helping me look into my family history. He’s away right now,’ I added irrelevantly.

‘And what have you two found out?’

‘Not much. A little from my cousin in Switzerland. You know, I was starting to think that knowing more about my French background would make me feel more comfortable here, but now I think I’m wrong. People still see me as American.’

‘You are American, Ella.’

‘Yeah, I know. But I have to change a little while I’m here.’

‘Why?’

‘Why? Because – because otherwise I stick out too much. People want me to be what they expect; they want me to be like them. And anyway I can’t help but be affected by the landscape around me, the people and the way they think and the language. It’s going to make me different, a little different at least.’

Rick looked puzzled. ‘But you already are yourself,’ he said, switching lanes so suddenly that cars behind us honked indignantly. ‘You don’t need to change for other people.’

‘It’s not like that. It’s more like adapting. It’s like – cafés here don’t serve decaffeinated coffee, so I’m getting used to having less real coffee or no coffee at all.’

‘I get my secretary to make decaf at the office.’

‘Rick—’ I stopped and counted to ten. He seemed to be wilfully misunderstanding my metaphors, putting that positive spin on things.

‘I think you’d be a lot happier if you didn’t worry so much about fitting in. People will like you the way you are.’

‘Maybe.’ I stared out the window. Rick had the knack of not trying to fit in but being accepted anyway. It was like his ponytail: he wore it so naturally that no one stared or thought him odd. I, on the other hand, despite my attempts to fit in, stood out like a skyscraper.

Rick had to stop by the office for an hour; I had planned to sit and read or play with one of the computers, but I was in such a bad mood that I went for a walk instead. His office was right in the centre of Toulouse, in an area of narrow streets and boutiques now full of Sunday strollers window-shopping. I began to wander, looking in windows at tasteful clothes, gold jewellery, artful lingerie. The cult of French lingerie always surprised me; even small towns like Lisle-sur-Tarn had a store specializing in it. It was hard to imagine wearing the things on display, with their intricate straps and lace and designs that mapped out the body’s erogenous zones. There was something un-American about it, this formalized sexiness.

In fact French women in the city were so different from me that I often felt invisible around them, a dishevelled ghost standing aside to let them pass. Women out strolling in Toulouse wore tailored blazers with jeans and understated chunks of gold at their ears and throats. Their shoes always had heels. Their haircuts were neat, expensive, their eyebrows plucked smooth, their skin clear. It was easy to imagine them in complicated bras or camisoles, silk underwear cut high on the thigh, stockings, suspenders. They took the presentation of their images seriously. As I walked around I could feel them glancing at me discreetly, scrutinizing the shoulder-length hair I’d left a little too long in cutting, the absence of make-up, the persistently wrinkled linen, the flat clunky sandals I’d thought so fashionable in San Francisco. I was sure I saw pity flash over their faces.

Do they know I’m American? I thought. Is it that obvious?

It was; I myself could spot the middle-aged American couple ahead of me a mile off just from what they were wearing and the way they stood. They were looking at a display of chocolate and as I passed were discussing whether or not to return the next day and buy some to take home with them.

‘Won’t it melt in the plane?’ the woman asked. She had wide, low-slung hips and wore a loose pastel blouse and pants and running shoes. She stood with her legs wide apart, knees locked.

‘Naw, honey, it’s cold 35,000 feet up. It’s not gonna melt, but it might get squished. Maybe there’s something else in this town we can take home.’ He carried a substantial gut, emphasized by the belt bisecting and hugging it. He wasn’t wearing a baseball cap but he might as well have been. Probably left it at the hotel.

They looked up and smiled brightly, a wistful hope shining in their faces. Their openness pained me; I quickly turned down a side street. Behind me I heard the man say, ‘Excuse me, miss, sea-view-play.’ I didn’t turn around. I felt like a kid who’s embarrassed by her parents in front of her friends.

I came out at the end of the street next to the Musée des Augustins, an old brick complex that held a collection of paintings and sculpture. I glanced around: the couple hadn’t followed me. I ducked inside.

After paying I pushed through the door and entered cloisters, a peaceful, sunny spot, the square walkways lined with sculpture, a neatly planted garden of flowers and vegetables and herbs in the centre. On one walkway there was a long line of stone dogs, snouts pointed upwards, howling joyously. I walked all the way round the square, then strolled through the garden, admiring the strawberry plants, the lettuces in neat rows, the patches of tarragon and sage and three kinds of mint, the large rosemary bush. I sat for a while, taking off my jacket and letting the psoriasis soak up the sun. I closed my eyes and thought of nothing.

Finally I roused myself and got up to look at the attached church. It was a huge place, as big as a cathedral, but all the chairs and the altar had been removed, and paintings were hung on all the walls. I’d never seen a church blatantly used as a gallery. I stood in the doorway admiring the effect of a large empty space hanging over the paintings, swamping and diminishing them.

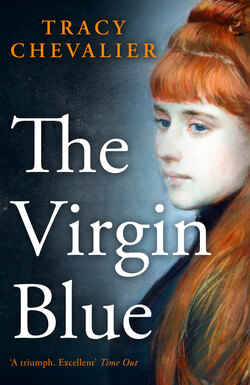

A flash in my peripheral vision made me look toward a painting on the opposite wall. A shaft of light had fallen across it and all I could see was a patch of blue. I began to walk toward it, blinking, my stomach tightening.

It was a painting of Christ taken off the cross, lying on a sheet on the ground, his head resting in an old man’s lap. He was watched over by a younger man, a young woman in a yellow dress, and in the centre the Virgin Mary, wearing a robe the very blue I’d been dreaming of, draped around an astonishing face. The painting itself was static, a meticulously balanced tableau, each person placed carefully, each tilt of the head and gesture of the hands calculated for effect. Only the Virgin’s face, dead centre in the painting, moved and changed, pain and a strange peace battling in her features as she gazed down at her dead son, framed by a colour that reflected her agony.

As I stood in front of it, my right hand jerked up and involuntarily made the sign of the cross. I had never made such a gesture in my life.

I looked at the label to the side of the painting and read the title and the name of the painter. I stood still for a long time, the space of the church suspended around me. Then I crossed myself again, said, ‘Holy Mother, help me,’ and began to laugh.

I would never have guessed there had been a painter in the family.