Читать книгу First Person - Valerie Knowles - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

A CELEBRATION

Cairine Wilson, Canada’s first woman senator, stood beside the white marble sculpture in the Senate antechamber, a slim, slightly stooped woman with widely spaced, deep blue eyes. With just the hint of a smile on her lips, she gazed shyly into the distance, skirting the towering figures of her two companions: John Diefenbaker, Canada’s, thirteenth prime minister, and Mark Drouin, the Speaker of the Senate, who took up a position slightly to her left and directly across from the beaming Diefenbaker.

It was a warm, soft evening — 10 June 1960 — and immediately in front of her, crowding the small oak-panelled anteroom, was a host of wellwishers and admirers. From Ottawa, across Canada, and the United States, they had come to watch the formal unveiling of this head-and-shoulders likeness of the Senator and to pay tribute to a remarkable seventy-fiveyear-old trailblazer.

Among them the Senator could pick out all of her eight children — Olive, the eldest, and then in order of birth: Janet, Cairine, Ralph, Anna, Angus, Robert, and Norma — old friends like Mrs D.C. Coleman and her sister, Mrs John Labatt; five of the six female senators then sitting in the Senate (Senator Mariana Jodoin was kept away by illness); the sculptor Felix de Weldon; colleagues of every political stripe; and dignitaries such as Keiller Mackay, lieutenant-governor of Ontario. The only notable absence was that of her beloved husband, Norman, who had died four years earlier.

Quiet and unassuming, she had dreaded this event, for even after thirty years as a senator, a lifetime of humanitarian service, and countless public appearances, Cairine Wilson disliked being centre stage. That was best left to a combative courtroom lawyer and politician like John Diefenbaker, who stood on the other side of the sculpture. Still, as she later admitted in a letter to a Montreal friend who had been very active in refugee work, Margaret Wherry, the ceremony “passed off much more easily and pleasantly” than she dared hope.1

This special event honouring Cairine Wilson might never have taken place at all if it had not been for the determination and organizing genius of two old friends, Kathleen Ryan and Isabel Percival, President of Ketchum Manufacturing of Ottawa, and a dedicated member of the Zonta Club of Ottawa, one of the many service organizations to which the Senator belonged. These two had made it all possible.

Unveiling of commemorative bust of Agnes Macphail, Centre Block, Parliament Buildings, 8 March 1955. Left to right: Margaret Aiken, MP, Charlotte Whitton, Mayor of Ottawa, Senator Cairine Wilson and the Hon. Ellen Fairclough, Secretary of State.

The idea for saluting Cairine Wilson in this way originated with Kathleen Ryan, who in 1984 recalled the deep impression that the Senator’s appointment had made on her when she was nineteen. A great admirer of Cairine Wilson, Mrs Ryan was vexed that no tangible monument had been erected to Canada’s first woman senator. Agnes Macphail, Canada’s first woman member of Parliament, was commemorated by a bronze bust outside the House of Commons, but in the Senate precincts there was no tangible reminder of Mrs Wilson’s many achievements. Kathleen Ryan therefore conceived the idea of installing a monument to Cairine Wilson in the Senate antechamber where, on 11 June 1938, Mackenzie King had unveiled a bronze tablet honouring the five Alberta feminists who had gone all the way to the Imperial Privy Council in London to prove that women were “qualified Persons” and therefore eligible for appointment to the Senate.2

As luck would have it, a sculpture that could serve as such a monument already existed. It was a white marble head-and-shoulders study of Cairine Wilson that had been sculpted twenty-one years earlier, in the summer of 1939, by an artist who has since become world famous, Felix de Weldon, (or Felix Weihs, as he called himself before his marriage), the sculptor of the renowned National Marine Memorial near Arlington Cemetery in Washington D.C. The artist, then a young Austrian refugee, had been recommended to the Senator by Miss Macphail, whose own portrait had been executed by the young man (This is the bust that now sits outside the House of Commons.) As Mrs Frazer Punnett, the Senator’s secretary at the time, recalls it, Miss Macphail came to the Senator’s office one day when Mrs Wilson was out and “left the message that perhaps because of [her] concern about refugees, she might want to give some consideration to a young sculptor from Austria.”3

It seems that the Senator was initially reluctant to have her portrait sculpted. For, as she confessed to her good friend, Dr Henry Marshall Tory, the noted educator and scientist, “At the time, a bust was the last thing which I desired but I finally agreed, for I had always regretted not having accepted Tait Mackenzie’s offer.”4 Evidently Agnes Macphail’s example and the Senator’s all too human desire to be recorded for posterity were too powerful to be ignored.

The Vienna-born and European-educated sculptor spent the whole summer at Clibrig, the Wilson summer home at St Andrews, New Brunswick, leaving only in mid-September after the outbreak of World War Two. With him went a clay model, which he later reproduced in white marble obtained from the fragment of an old Greek column that he had picked up in a New York antique store.5 The completed marble version was taken to Ottawa where it was installed in the library of the Manor House, the stately Wilson home in Rockcliffe Park.

Kathleen Ryan, it seems, recalled this impressive sculpture when she began to entertain ideas about honouring her illustrious friend. So did Isabel Percival, who, like Mrs Ryan, was sure that the Wilson family would be glad to donate it for the purpose that they had in mind. The family was approached and after permission was granted, Mrs Ryan and Mrs Percival went to see Ellen Fairclough, Diefenbaker’s minister of citizenship and immigration.6

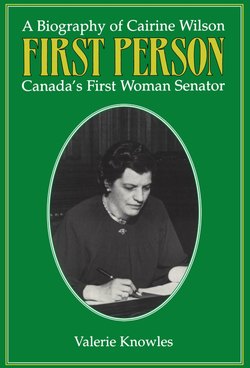

Cairine Wilson’s portrait bust. Sculpted by Felix de Weldon in 1939, it now sits in the Senate ante chamber.

As a close friend of Isabel Percival and the first woman to be appointed to a federal cabinet, Ellen Fairclough was the logical link with the Conservative government of the day. She was also a fortunate choice because she embraced the idea with enthusiasm, approaching the Prime Minister and the Speaker of the Senate, whose permission was required before the bust could be placed in the Senate antechamber.7

The interview with the vivacious, spirited Mrs Fairclough was not without its amusing overtones, because at some point Mrs Ryan raised the question of the bust’s low neckline. It appears that the generous expanse of exposed flesh that the sculpture depicted gave her cause for concern. Would it not invite ribald comments from some male observers? When Mrs Fairclough learned of these fears, she burst out laughing, but then rallied with the reply that “certainly everything should be done to make the Senator acceptable to the gentlemen of the Senate.”8

Eventually everything possible was done to rectify the situation. Felix de Weldon was consulted, and because he weighed much less than the sculpture, it was decided that he would come to Ottawa to make the necessary adjustments to the piece rather than have it delivered to his studio in Washington.9 In the late winter of 1959-60, therefore, he journeyed to Ottawa where he spent several days modifying the bust by carving the neckline of a dress and giving it some texture. Years later Mrs Ryan would express the view that the sculptor had done “a good job of hoisting Cairine Wilson’s dress.”

Since 1959-60 was World Refugee Year and because the Senator had long been deeply involved with the refugee cause, her two friends also included a couple of imaginative money-raising projects for the World Refugee Fund in their plans: a Senator Wilson Testimonial Fund and a garden party. A prestigious committee, composed of the two organizers; Senator Olive Irvine; Beatrice Belcourt, a longtime friend; Colonel George Cavey, the former manager of Birks Jewellers and a member of St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church; Mrs Farrar Cochrane, a family friend; Senator Muriel McQueen Fergusson, a colleague and good friend from New Brunswick; Constance Hayward, a close friend who had served as the executive secretary of the Canadian National Committee on Refugees; Mrs A.K. Hugessen, a prominent member of that organization; and Yetty Robertson, wife of the distinguished Under-Secretary of State for External Affairs, Norman Robertson, solicited contributions for the testimonial fund, and the Local Council of Women staged a mammoth garden party in the spacious grounds of the Manor House. Thanks to superb organization and beautiful weather, the garden party was pronounced a huge success, raising $1,600 for the World Refugee Fund.

It had indeed been a memorable week — and an exhausting one. On Monday the Senator had returned from Washington, where she had received an honorary Doctor of Letters from Gaudet College, the only institution in the world for the higher education of the deaf, another cause with which Cairine Wilson had long been identified. Then, on Wednesday, there had been the garden party. Now, here she was in the precincts of the Red Chamber to watch John Diefenbaker, the wild-eyed populist shunned by the eastern establishment, unveil a twenty-one-year-old portrait of her, a leading member of that establishment. Ellen Fairclough opened the proceedings, then presented Mr Diefenbaker, who said in his tribute:

...I think of her as one who in the field of social and humanitarian service made a contribution as comprehensive as the numberless organizations in that field. I could name them. To do so would simply mean to name practically all those voluntary organizations which bring about the translation of the concept of brotherhood to those lesser privileged. In that field too Senator Wilson has made a contribution that is recognized throughout the world.10

After the Prime Minister had unveiled the portrait, the Senator gave a brief address, concluding her remarks with the observation:

It has been a great joy and satisfaction to me to know, and to be assured by my colleagues of my own sex that I made the way more easy for them. My husband lived in constant dread that I should do something which would bring the family and my sex into disrepute.

All I can say is, I know that I am unworthy of the tribute you have paid me today.11

It was then the turn of Mark Drouin, Speaker of the Senate, to make a few remarks, and he said in part:

The Honourable Cairine Reay Mackay Wilson completed recently thirty years in the public service of our country. Throughout this long and fruitful career she has won the esteem and admiration of all Canadians for her devotion to the common weal, the maturity of judgment and wisdom of counsel she has constantly displayed in the discussion of affairs of state, her successful initiatives for the relief of suffering and the redress of existing evils at home and abroad, her effectiveness as an advocate of social justice and security, and her personal qualities of charm, friendliness and dignity. We are grateful to her for her admirable contribution not only to the work of this house but to its reputation and prestige.12

John Keiller Mackay, Lieutenant-Governor of Ontario, was caught quite unprepared when asked to bring the proceedings to a close with a few words. Nevertheless, he managed to rise to the occasion with some fulsome praise for his friend and clanswoman, observing, “Her head is crowned not only with silver, but respect, admiration, esteem and love.”13

It would have been next to impossible for a stranger watching the proceedings to reconcile the subject of all these tributes with the tributes themselves, for Cairine Wilson was not, to use today’s overworked expression, a “charismatic” figure — far from it. Nevertheless, she had many qualities that more than made up for this: monumental compassion and loyalty, charm, political acumen, iron determination, an infinite capacity for hard work, a finely tooled feeling for style and propriety, and a certain magic authority. These played an invaluable role in her remarkable career. But so did certain traits that she inherited from her Scots-Canadian forebears. And it was her family’s position in Montreal society that allowed the Senator to move freely within the eastern Canadian establishment and to use it to pursue many of her goals.