Читать книгу First Person - Valerie Knowles - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

THE MACKAYS

Cairine Wilson was born into a family of wealth. Perhaps even more important, she was born into a Scots-Canadian family that figured prominently in Montreal’s English-Scots establishment, an insular society that flourished in Montreal’s famous Square Mile, those several blocks in central Montreal where the rich built their mansions in the last half of the nineteenth century and the first years of the twentieth. Until World War 1 thinned the ranks of their youth, they held undisputed sway — a colonial gentry slavishly imitating British social manners and mores and marrying within their own exclusive social circle.

When the future senator was born, in 1885, the British Empire was approaching its zenith and privileged Victorians everywhere basked in opulence and smugness. It was an epochal year for the young dominion of Canada. The financier and politician, Donald Smith, in an act charged with symbolism, drove a plain iron spike into a railway tie at Craigellachie, British Columbia, thereby completing the celebrated Canadian Pacific Railway and welding East to West. In a quite different sequence of events, the messianic Métis leader, Louis Riel, met his end on a jail gallows in Regina after leading his people in the North West Rebellion against the government at Ottawa. With his death he opened up a great rift between French and English-speaking Canadians, because while the former regarded him as a hero and a martyr, English-speaking Canadians denounced him as a rebel and a traitor who richly deserved his fate.

Closely associated with all these developments was Montreal, the metropolis of Canada, a rapidly growing city with an English-French population of approximately 145,000 and a thriving commercial-manufacturing sector dominated by English-speaking Canadians. It was a beautiful city with a plethora of gleaming church spires and a tree-covered mountain that sloped gently down to an elegant residential artery, Sherbrooke Street. Before it was expropriated for a public park in 1875, the mountain had been the preserve of private property owners who had dotted it with farms, orchards, gardens and villas. Now, a decade later, its largely unspoilt beauty was enjoyed year-round by all kinds of people, many of them sports enthusiasts who found it a choice location for riding, tobogganning and snowshoeing.

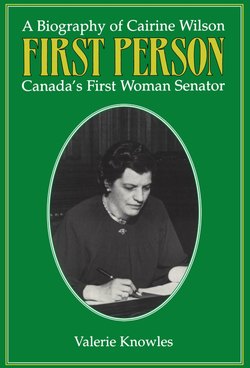

Cairine Wilson as a young girl.

In sharp contrast to the peaceful surroundings of Mount Royal was the busy port area which abutted onto the broad St. Lawrence River. The first port in the world to be electrified, Montreal now welcomed the arrival of vessels from some thirteen steamship companies, one of these being the renowned Allan Line. Pre-eminent on the Atlantic, it had been founded in 1854 by a group of friends led by the Scottish-born Montrealer, Hugh Allan, later Sir Hugh Allan.

Just north of the docks and the warehouses, but well within earshot of the shipping sounds and the factory whistles, was the impressive financial and commercial district. Here, clustered on Notre Dame and St. James Streets, could be found an array of fine buildings that had been erected in the economic boom of the 1860s when architects vied with each other to design impressive facades. Reflecting the unabashed pride of their owners, these edifices flaunted carved and garlanded walls, pillared porticoes and entrances decorated with a profusion of detail. Now, in the 1880s, they were being eclipsed by larger and even grander buildings, some of which were built to meet a growing demand for rental office space; Montreal was moving into the office age, a phenomenon that continues unabated today.

Despite all the changes that the city had undergone over the years, however, the sharp division that had always existed between French and English-speaking Canadians remained. It expressed itself most visibly in the choice of residential area. For, if one took St. Lawrence Main as a dividing line, nearly all the inhabitants living east of it were Frenchspeaking while virtually all those west of it were English-speaking, whether of English, Scots, Irish or, in rare cases, American origin. Only occasionally did the two groups overlap the conventional barrier.

Commenting on these “two solitudes,” a contemporary observer wrote:

Montreal is a striking exception to the text that a house divided against itself cannot stand. Its divisions are so fundamental and persistent that they have not diminished one iota in a century, but rather increased. The two irreconcilable elements are Romanism and Protestantism; the armies are of French and English blood. The outlook for peace is well-nigh hopeless, with two systems of education producing fundamental differences of character, and nourishing religious intolerance, race antipathy, social division, political antagonism, and commercial separation.

Nevertheless, this city of disunion flourishes as the green bay-tree, with a steady if not an amazing growth, which is due chiefly to the separate, not the united, efforts of the races.1

In this thriving port and manufacturing centre the Mackay family played an important role, having been established there for over fifty years, thirty of them highly prosperous ones. Cairine Wilson’s father, Robert Mackay, was a wealthy man in his own right and one of Canada’s leading businessmen. Her mother, Jane Baptist Mackay, had similar bourgeois roots, being the daughter of George Baptist, a successful logging merchant, who had emigrated from Scotland to Canada in 1832 and later created an industrial empire in Quebec’s Saint Maurice region.

The first Mackay relative of Cairine Wilson to settle in Canada also emigrated from Scotland to Quebec in 1832. He was her great-uncle, Joseph, the third youngest of ten children born to William and Anne Mackay. The Mackays lived in remote Sutherland, a rugged county of heather-clad moors and precipitous mountains that overlook long dark lochs. Here, in the beautiful strath of Kildonan, William was a small tenant farmer, or crofter, until he and his family were uprooted by the notorious Highland clearances. Today almost forgotten, except in the Highlands, the “clearances” was the name given to the removal of crofters and subtenants from their holdings to permit the conversion of tilled land to pasturage. Actively supported by the law and by the established Church of Scotland, they were widespread in the late eighteenth century and the first half of the nineteenth when sheep farming was introduced by many Highland landlords seeking a better return on their dwindling capital. On the Duchess of Sutherland’s estates alone, where the Mackays were tenants, some fifteen thousand crofters were evicted from their crofts between 1811 to 1820, armed force often being used to drive them from their homes.2

The first warning of the removals that involved the William Mackay family came in October 1818 when a man roused the Reverend Donald Sage at the manse in Achness to report that the rent for the half-year ending in May 1819 would not be collected because plans were being made to lay the districts of Strathnaver and Upper Kildonan under sheep. The actual evictions took place the following spring when, thirteen days before the May term, an army of burners — sheriff-officers, constables, factors, shepherds and servants from Dunrobin Castle, the Duchess of Sutherland’s home, — descended on the townships along the Naver and on Kildonan and torched the victims’ homes one by one. In this devastating Clearance, reports Donald Sage in his Memorabilia, “The whole inhabitants of Kildonan parish, nearly 2000 souls, were utterly rooted and burned out.”3

Some of the dispossessed emigrated to Canada and the United States while others accepted small, inferior lots of land on the coast, the theory being that they could maintain themselves by reclaiming waste land and supplementing its produce by collecting and eating edible seaweed. William Mackay eventually settled at Roster in Caithness,4 that bleak, almost treeless county that occupies the extreme northeast of Scotland. There Joseph spent his days until he left for Canada in 1832, the year of the great cholera epidemic. With him went a fund of heart-breaking stories concerning his family’s eviction from Kildonan, lore which would be passed down through succeeding generations of Mackays in Canada and which would eventually help to shape Cairine Wilson’s thinking on immigration and refugees.

Twenty-one-year-old Joseph probably sailed from the Highland port of Aberdeen in the late spring or early summer of 1832 on one of the many overloaded emigrant ships that carried half-starved and ailing passengers to North America. Among the sickly passengers would be many who had contracted cholera, either before setting out or on the voyage. However, it appears that the young man was not among them. Nor did he catch the disease after his arrival in Canada, where it was introduced by the Carrick when it docked at the quarantine station below Quebec on 8 June 1832. That Joseph did not contract the disease is surprising because Montreal that summer was in the grip of a cholera epidemic. No matter where he went in the demoralized town, Joseph would not have been able to escape the mournful sound of the incessantly tolling death bell or the spectacle of coffin displays and posted advertisements for cheap funerals. He would probably even have come across whole streets that had been depopulated either by death or by the flight of panic-stricken inhabitants to country villages. It was certainly not an auspicious beginning for a stranger in a new land, as his brother, John, realized when he wrote to Joseph from Roster on 20 February 1833:

I write you these lines in hopes of hearing from you and of your state and to let you know of our state. We have received 2 letters from you the one sent to Aberdeen we found first which gave us great relief to hear of you being in life, and health in the place where the Lord cut down so many by Death, we would write you sooner if not your father was poorly a long time but he is now getting better, and myself is still the same, all the rest in good health and the whole of them lamenting you to be in a wild savage country, and that you might do well enough near your own parents besides being among such as you mentioned, you have left the place where there is hardly any example and your expence will ballance the outcome of your trade.5

Probably no other letter better illustrates two leitmotivs that run through the Mackay family history and Cairine Wilson’s adult years: a deep religious faith and an interest in sound business practice. Joseph himself certainly exemplified these traits. However, unlike his dour brother, he was of a sunny, optimistic nature. Despite John’s forebodings and entreaties to return to Caithness, Joseph stayed on in the New World, setting up as a tailor and merchant on Montreal’s Notre Dame Street, not far from the busy harbour. It was to this address that his concerned father, William, wrote on 24 October 1834:

Dr. [Dear] Child we are something tedious concerning the great expence of your houses and trade and that we could not fully understand what are you selling out to make up your expence you know also that our wishes and desires is not in the least abating for seeing you in this Country if you would be permitted, but we refair it to your Makers providence and to your own mind as wishing it to be guided by him and we trust that yourself hath made up your mind as considering a measure of both kingdoms.

...P.S. We are regrating that you did not enlarge more how do you spend the Sabath or is there a sound preacher among you all.6

Clearly, the “Dr. Child” had joined the burgeoning ranks of other Scots, who were then carving out a commanding position in the economic life of Canada. Nowhere was the leadership of these men in the Canadian business world more conspicuous than in Montreal, a city where Scots not only dominated business but also played a prominent role in the founding of institutions, the building of churches and the launching of commercial organizations. Although he could not have known it in 1832, Joseph too would eventually become a prominent member of this group of self-made tycoons.

Joseph Mackay, Great-Uncle of Cairine Wilson.

No doubt impressed by his brother Joseph’s rising fortunes, Edward Mackay emigrated to Canada in 1840 and, after spending six months in Kingston, Ontario, settled in Montreal where he became a clerk in Joseph’s wholesale drygoods firm. By 1850, he had demonstrated such industry and business acumen that Joseph took him on as a partner, the firm becoming known in May of that year as Joseph Mackay and Brother. The business grew so quickly that in December 1866 it was reported that the previous year’s sales had been well in excess of one million dollars and that the two bachelor brothers were “wealthy.”7

By then, Joseph had anticipated a trend on the part of the fashionable in Montreal by moving his place of residence from St. Antoine Street, not far from the harbour, north towards the slopes of Mount Royal. There, on Sherbrooke Street at the corner of Redpath, just below the mountain, he had purchased several lots from the estate of the late S.G. Smith and had proceeded in 1857 to build a stone mansion, which he named Kildonan Hall after his birthplace in Sutherlandshire.8 Before it was razed in 1930 to make way for the Church of St. Andrew and St. Paul, Kildonan, as it was known, was one of the most striking on a wide avenue of impressive mansions. As the historian and journalist, Edgar Andrew Collard, has observed, Joseph Mackay’s residence would have been imposing even if it had been situated near the sidewalk. But what really made it stand out was its siting in large shady grounds that resembled those of a magnificent country estate.9 Near the southeast corner of the property — adjoining a finely worked wrought-iron fence — stood two stone gateposts, which flanked a curving driveway that swept up to a pillared front porch. To the right of the house, as you faced it, was a porte-cochere, to the left, a large conservatory, which featured the prized marble statue, “Diana,” one of several legacies that Joseph earmarked for his niece, Henrietta Gordon, who lived with her uncles at Kildonan until she died in 1883, shortly after the death of Edward. Still later, after Senator Robert Mackay’s death, the statue would find its way into Cairine Wilson’s possession.

Like most large neo-classical houses designed for the very affluent in Victorian Canada, Kildonan had high ceilings and a square floor plan. Opening off the front door was a spacious, but dark, entrance hall graced by a wide, sweeping, staircase. Overlooking this — and bearing mute testimony to Joseph’s Scottish origins — was an impressive stained glass window depicting Sir Walter Scott’s narrative poem, “The Lay of the Last Minstrel.”10

Kildonan was not only architecturally imposing — with its Italianate touches and large size — it was also richly furnished with art work and heavy furniture, much of which had been purchased by Joseph on his overseas buying trips. The result was an exceedingly gloomy house that bespoke a certain Scottish dourness and fervency of purpose.

Another Montreal landmark closely identified with Joseph Mackay was the Mackay Institution for Protestant Deaf-Mutes, located on the west side of Decarie Road, now Decarie Boulevard. The Montreal merchant first became involved with handicapped children in 1874 when a struggling institution, known as the Protestant Institution for Deaf-Mutes and for the Blind, approached him for financial assistance. A kind man, who was keenly interested in the welfare of the deaf child, Mackay became a governor of the institution and then, in 1876, when larger premises were urgently required, he donated both the property on Decarie Road and a four-storey building where classes could be held. He also assumed the presidency of the school, which in 1878 was renamed the Mackay Institution for Protestant Deaf-Mutes in his honour.11

In a speech on the occasion of the laying of the building’s cornerstone Joseph Mackay waxed eloquent with the hope that “for years and generations to come the Institution may, through Divine favour, prove a source of manifold blessings to the afflicted classes whose good it seeks, and may never lack warm-hearted and generous friends and wise and godly instructors to carry on the work.”12 The wealthy Montreal merchant would have been gratified to know that members of succeeding generations of Mackays, Cairine Wilson among them, would play a leading role in the school’s affairs.

“Kildonan.” Mackay family home on Sherbrooke Street West, Montreal. This site is currently occupied by St Andrew’s and St Paul’s Presbyterian Church. Its church hall is called Kildonan Hall after the original house.

In addition to the role that he played in the Mackay Institution for Protestant Deaf-Mutes, Joseph could also take great satisfaction and pride in the contributions that he was making to his church. A devout Presbyterian, who was deeply conscious of the obligations of God’s blessings, Joseph gave generously to the church. He also became actively involved in its work, helping to establish the Presbyterian College of Montreal, which opened in 1867, and serving for a number of years on its board of managers. While travelling on business in the provinces, he kept “his eyes open to the spiritual state of those with whom he came in contact” and when he detected a need for additional Presbyterian ministers, he arranged for Scottish clergymen to come to this country. All told, he brought out ten to twelve ministers of the Free Church of Scotland at his own expense.13 Following his retirement from business, he became interested in the missionary work of the church and whenever he travelled in Canada or overseas, he made a point of visiting missionaries.14

Joseph Mackay died in 1881, but not before sending a last message to his minister. Asked if he had anything he wanted to convey to this pious gentleman, Joseph pondered and then said, “Just this: ‘Do good as you have opportunity.”15 Two years later Edward died, still a bachelor. By now, however, the flourishing drygoods business had been turned over to the brothers’ three nephews, Hugh, James and Robert, sons of their sister Euphemia and her husband, Angus Mackay, of Lybster, Caithness and nearby Roster.

The youngest of the brothers was Robert, Cairine’s father. Born in Lybster, Caithness, he had followed Hugh and James to Montreal in 1855 when he was only sixteen. Once arrived in Canada, he had demonstrated his Scots faith in education by taking up bookkeeping and commercial studies. In a letter to a friend in Scotland, written in 1858, he noted that he had begun bookkeeping. Then he went on to observe, “for a time at least I intend to follow commercial pursuits and, if successful, I ultimately hope to return to the land of my fathers and settle down in rural life as a quiet useful farmer.”16 But not alone it seems. In the draft of a letter intended for his cherished friend Catherine Macdonald he enlarges upon this dream, voicing sentiments that hint at some of the qualities that helped to shape his remarkable career:

I was also glad, for certain reasons, to hear that some of the folk in Newlands have not yet got married as it permits me to hope, that, should my plans for the future be crowned by a kind Providence with success — should I by honest persevering industry and prudent economy gather enough of this world’s gear to buy me a snug little farm in dear auld Scotia and enable me to settle down in quiet independence with the beloved object of my fond affection, I might win her consent to share it with me.17

Robert never realized his youthful dream to marry his beloved and to settle down in Scotland as “a quiet useful farmer.” But he did fulfill his ambition to succeed in the field of commerce. Shrewd, able and industrious, he personified those traits that enabled the Scots-Canadians of his and his uncles’ generations to become the dominant group in the commercial life of Montreal, indeed of Canada. His climb up the ladder of business success was aided, however, by substantial legacies. Along with his brothers Hugh and James, Robert received an equal share of the residue of his Uncle Edward’s estate. Then, when James died unmarried in 1889, he inherited, along with Hugh, the remainder of James’s estate. Finally, on the death of bachelor Hugh, in 1890, Robert became the sole legatee of that merchant’s estate and the proprietor of all the residue of Edward Mackay’s succession.

Robert could have frittered away his inheritance, but since he possessed a sound business sense and a marked distaste for frivolity, he invested his legacies providently in an impressive range of stocks, bonds and real estate properties. An editorial that appeared in the Lethbridge Herald after the death of his son George illustrates the Senator’s prudence (Robert was elevated to the Senate in 1901) and aptitude for business, two qualities that he passed on to his daughter, Cairine, who would have made an excellent businesswoman had she embarked on a business career.

When the old Senator made a disbursement for the advancement of the business, he was wont to ask George for a memorandum of the requirements, which he would carefully put away, saying, “There should be a record of this for those that come after.”

This methodical manner was an ever-present ideal with the uncles and the fathers in the conduct of their affairs in the important merchandising business that they founded in Montreal and in all their transactions that led to the foundation of a considerable fortune.18

In 1893, twenty-six years after becoming a partner in the family firm, and three years after becoming its head, Robert Mackay retired from the drygoods business to devote more time to managing the enormous Mackay estates and to meeting the demands of his wide assortment of business commitments. These multiplied so rapidly that before his death in 1916 he was a director of sixteen companies, including such illustrious institutions as the Bank of Montreal, the City and District Savings Bank, the Dominion Textile Company and the Canadian Pacific Railway. Given his formidable list of directorships and his active participation in the affairs of such companies as the Bell Telephone Company, which he served as vice-president, it is not surprising that he earned the reputation of being the most sought after man in Canada for directorships. In fact, the Montreal Standard placed him among the twenty-three titans who were preeminent in the Canadian financial firmament in the opening years of this century.19

Hon. Robert Mackay, father of Cairine Wilson.

When one contemplates the daunting number of directorships and company offices Robert Mackay held, one might conclude that he had little time for anything else. But such was not the case. As befitted a leading member of Montreal’s business community, he joined the Board of Trade, becoming president of it in 1900. He was also a member of the Board of Harbour Commissioners, which he served as president from 1896 to 1907. In tribute to his farsighted leadership, a stretch of wharves was named after him as was the tug, “the Robert Mackay.” Decades after his death this squat boat could still be seen plying the waters of Montreal harbour, not far from the Harbour Commissioners building and the richly furnished third-floor boardroom where the Senator and his fellow commissioners met weekly to manage the port and plan its future. Cairine Wilson’s father also played a leading role in preserving the traditions of his native Scotland, serving at one time as president of the local St. Andrew’s Society and as honorary lieutenant colonel of the 5th Regiment, Royal Highlanders of Canada. His abiding love of tradition and history would be inherited by his daughter, Cairine, who, in her adult years, would amass scrapbooks crowded with clippings relating to her family and things Scottish.

When it came to business acumen and moral earnestness, Robert Mackay resembled Joseph and Edward. But unlike his “kindly uncles,” as he once referred to them, and his brothers, Hugh and James, he abandoned celibacy for marriage and the role of paterfamilias. On 10 May 1871, at the home of the bride’s father, in Trois Rivières, Quebec, which in those days was called Three Rivers, he married Jane, the twenty-one-year-old daughter of George and Isabella Baptist.

A self-made lumber baron, George Baptist had begun his career as a sawmill employee in Dorchester County, Quebec in the 1830s. From these humble beginnings he had gone on to become a member of the “brotherhood of the Saint-Maurice barons,” a group of powerful logging entrepreneurs that exploited the enormous timber wealth of the Saint-Maurice region of Quebec. By the time that Robert Mackay became his son-in-law, this transplanted Scot had created an industrial empire that produced between 25 to 30 million feet of lumber each year. He had also succeeded in becoming an outstanding member of Trois-Rivières' growing bourgeoisie. Of his eight children, five were daughters, Jane, or Jeannie, as she signed herself in her letters to her husband, being the youngest. Like Jane, the older girls all married businessmen. Phyllis married James Dean, a Quebec City merchant; the other daughters married local men: Isabella, George Baillie Houliston, a lawyer, banker and broker; Margaret, William Charles Pentland, an accountant; and Helen, Thomas McDougall, a metallurgist.20

Robert, the up-and-coming merchant and financier, was thirty-two when he married Jane Baptist in her family home in Trois Rivifcres. From a Notman photograph taken in 1878, we can see that the young Mrs Mackay was, if not exactly pretty, at least tall and handsome, with a high forehead and fair hair that was parted in the middle and then pulled straight back. Resplendent in a dark dress whose severity is relieved by a border of brocade, she stands beside a draped table and stares pensively at the camera. Even more impressive in appearance is her sombre husband: a strikingly good-looking man with deeply chiselled features, a high intellectual brow and a short cropped beard. In later photos, taken when he was in his fifties, the beard appears more luxuriant, the face fuller and the expression, if anything, sterner.

The somewhat hazy picture that emerges of Jane Mackay is of a kind woman who was dominated by her husband and plagued by ill health. A family story, perhaps apocryphal, claims that Robert Mackay would dole out some money to his wife for groceries each month and then pocket any that she left on the hall table after she had made up her monthly accounts. Certainly she was no bold, high-spirited chatelaine, as this rather pathetic excerpt from a letter written in 1879 indicates:

...I regret dear Robert that home is not more happy for you. I know that you feel that you have more to bear with than a great many, but you must not forget that I have my own little troubles & I know I am not able to bear up the way I ought to. I will try in the future to keep these little things to myself & not trouble you more than I can help.21

Just what she meant by these “little troubles” is not known. But no doubt the reference alludes, in part, at least, to assorted ailments that afflicted her during her lifetime and to the demands made upon her far from robust constitution by frequent and debilitating child-bearing. The first child, a daughter, Louisa, had arrived during the first year of marriage and had died shortly thereafter. Then, in rapid succession, had come Angus Robert (1872), George Baptist (1874), Hugh (1875), Euphemia (1876) and Isabel Oliver (1878). At the time that she penned her rueful observations in a fine copperplate hand to Robert, she was pregnant with her seventh child, Anna Henrietta, who would enter the world on 25 December 1879. Mercifully for Jane, there would be a six-year interlude until Cairine arrived in 1885. Edward, the last of the children, would be born in 1887.

Cairine Mackay was born in February 1885, a month that would later prove to be a portentous one for Montreal. For it was in February that a Pullman porter from the Chicago train was admitted to the Hotel Dieu hospital with a slight skin eruption that was later diagnosed as smallpox. The disease quickly spread to other patients and before long a major epidemic was in progress. Goaded into drastic action by a public outcry for sterner measures, the city finally introduced compulsory vaccination that fall and soon the epidemic petered out, but not before some three thousand lives had been claimed and thousands of French Canadians had rioted in the streets to protest the new measure.22

Interestingly enough, the day that Cairine Mackay appeared on the scene — Wednesday 4 February — a notice appeared in the The [Montreal] Gazette advertising the sale by auction of her father’s semi-detached stone house on Edgehill Avenue off Dorchester Street West. According to the ad, this most comfortable of family residences boasted bay windows and a wide verandah in the rear as well as a “faultlessly laid out” interior and “light and cheerful” rooms. Even allowing for some descriptive license on the part of the copy writer, it must have been an inviting house, not gloomy and depressing like Kildonan. However, it was at Kildonan that Cairine Mackay was born and it was here that she would pass her impressionable years before her marriage in 1909.

Robert Mackay had moved his family into the Sherbrooke Street mansion shortly before the birth of his youngest daughter and not long after the death of his cousin, Henrietta Gordon, who, by the terms of Joseph’s will, was allowed to occupy Kildonan for a period of five years after her uncle’s death. For the next forty-five years, until its demolition in 1930, the house would be owned exclusively by Mackays or by the Robert Mackay estate.

The child born to Jane and Robert Mackay on 4 February was christened Cairine (Gaelic for Catherine, the name of Robert’s older, unmarried sister and of his beloved cousin, Catherine Gordon) and Reay (after the chief of the Mackay clan) on 23 June 1885 by the Reverend A. B. Mackay at Crescent Street Church. With this ceremonial sprinkling of water, she was formally initiated into the Presbyterian church, one of her great-uncles’ preoccupations and destined to be a major force in her own life.

The details of Cairine Wilson’s childhood are sketchy because she seldom referred to it in conversations with her own children. We do know, though, that her gruff, demanding father exercised a powerful influence and that relations between the parents and their children were punctilious, so formal as to perhaps move the wistful daughter to say in an interview granted in 1930:

I earnestly believe that parents and children both gain more by establishing a close comradeship than by the parents standing aloof and accepting the position of judge, disciplinarian and critic of their children. There is no reason why parents should not be pals of their children and still have respect and reverence and obedience from them. In fact I think they are more likely to possess these from children who feel that their parents are understandingly one with them, than are the parents who insist on implicit obedience and rigid respect without having first won the loving confidence of their children.23

The stiff relations between parents and children could not detract, however, from the basically warm, kind nature of Jane Mackay. To her children in distress, she was the embodiment of sympathy and loving attention, as young Cairine realized all too well when, on a trip to Europe, she was taken ill and longed for her mother.24

Mrs Robert Mackay, mother of Cairine Wilson.

We can assume that as the child of a wealthy family that had just become part of the elite of this young country, Cairine was raised according to the essentially bourgeois standards of her class. These called for ladies to speak softly, to not appear intellectual and to strive at all times to be decorative. Instead of sipping madeira or port at the table after dinner, as did the men, it was their lot to withdraw to spacious drawing rooms to chat about children, servants and fashion and to indulge in the latest society gossip. In 1892, in Montreal, this would probably have been dominated by revelations concerning “the most sensational elopement” the city had ever known, that of Jack, the eldest son of Andrew Allan, one of the millionaire partners in the Allan Royal Mail Steamship Line, and the wife of a bank inspector named Hebden.25

But if the latest doings in society were welcome topics of conversation, some subjects — money and sex — were taboo. Indeed, ladies were not even supposed to think about them. Probably the greatest taboo, however, was feeling. Not only did a member in good standing of the bourgeosie, especially the Scots-Canadian middle class, not express emotion, he or she did not even mention it. People whose work owed its existence to feeling — writers, artists, actors — were as declassè as tradesmen. Equally horrendous was marriage outside this bourgeoisie unless it was to someone from the British gentry or aristocracy. Anna Mackay upset her father merely by marrying an American. Robert Loring might be charming and well educated, but nevertheless he was an American and that alone placed him beyond the pale!

Like most heads of Scottish-Canadian families, Robert Mackay was a strict disciplinarian who actively supported a “spare the rod and spoil the child” regime. Since he was also a devout Presbyterian, he insisted that his children be raised according to the dictates of Scottish Presbyterianism. One of the driving forces of the Scottish character, it emphasized the duty of each Christian to manifest God’s will in everything he did or, as the more lyrical phrase has it, “to glorify God and enjoy him forever.” Not surprisingly, this translated into a divine calling to work (the Protestant work ethic) and a God-given responsibility to demonstrate initiative, risktaking and foresight. Yet, contrary to what many people think, it did not result merely in a desire to accumulate material riches. Along with it went the concept of stewardship, the belief that individuals should use their talents and any wealth that they had to benefit their fellow brothers and sisters.26

These and other Calvinistic positions — for Presbyterianism was deeply rooted in Calvinism — were incorporated in the faith’s standard catechisms: the very detailed Larger Catechism and the less formidable manual of instruction, the Shorter Catechism (“for such as are of weaker capacity”). Coming as they did from a staunch Presbyterian home, Cairine and her siblings were instructed in the Shorter Catechism, which has 107 questions and answers, the first of which reads: “What is man’s chief end? Man’s chief end is to glorify God and enjoy him forever.”

Luxury for the Mackay children was therefore tempered not only by a very strict upbringing but also by the teachings of their church. Perhaps because of this, the boys, with the notable exception of the painfully shy and abstemious Edward, earned a reputation for being rather wild in their youth. In fact, one of their chief delights was to down a few drinks and then career around the top of Mount Royal on horseback.

Young Cairine, however, never rebelled overtly against her puritanical upbringing or against the earnest self-denial and self-discipline that Scots Calvinism implies. Nevertheless, all these influences made for a very shy, reserved woman who found it difficult to express emotion and who was seldom demonstrative, even with members of her own family and friends. Those who came to know her well, though, would discover that beneath the reserve was an abundance of warmth and compassion, qualities that perhaps were inherited from her mother and then nurtured by circumstances. Much more obvious were superb organizing skills and her talent for righting misunderstandings with tact and diplomacy. These were developed as early as the age of twelve when her mother began saying, in the event of any domestic difficulty, “Cairine will settle it.”27

For those privileged to live in Montreal’s large ornate houses in the late Victorian period, life had a lot to offer. Still, the early childhood years that Cairine spent at Kildonan were not particularly happy ones. As her mother was frequently ill and Kildonan was a large household, she had a lot of responsibility thrust on her shoulders, including the care of her younger brother, Edward, to whom she was very close before her marriage. Far removed from her daily orbit, because of their age differences, were her older brothers, Angus, George and Hugh. Yet Cairine greatly admired the eldest, Angus, perhaps because he was more widely read than the others and she had developed a taste for books and learning. She had to do most of her admiring from afar, however, because Angus went off to Boston to study engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and after his graduation, in 1894, settled in North Dakota where he supervised some of his father’s mining interests. George, the second eldest, also left Montreal, to attend MIT briefly and then, after a short stint as a bank clerk in Montreal, to serve in the Boer War. After the conclusion of hostilities, in 1902, he struck out west, and put down roots in Alberta, eventually becoming one of Lethbridge’s best known and most publicspirited citizens. Hugh remained in Montreal, where he graduated in law from McGill University in 1900 and went on to become one of the city’s most prominent corporation lawyers and company directors.

In her early childhood years, Cairine would have seen more of Edward and her three sisters, Euphemia (Effie), Isabel and Anna than her older brothers. For this reason the early deaths of the older sisters, Euphemia and Isabel, were especially poignant. Both succumbed to that great scourge of Victorian times, tuberculosis, Isabel dying in 1894 when she was sixteen, and Effie in 1897 at age twenty-one. Isabel’s illness and subsequent death perhaps accounts, in part at least, for the sad expression that is so evident in an undated photograph of Cairine. Taken when she was around eight or nine years of age, it shows a very solemn youngster clasping a singlestemmed rose as she poses in a white dress. What is most striking is not the dress, the long, gently flowing, dark hair, or the somewhat heavy features, but the eyes. Deep set and widely spaced, they have an inescapable look of sadness.

The Montreal that Cairine came to know between 1890 and 1909, when she married and went to live in Rockland, Ontario, was only a fraction of the city — indeed, only a portion of the district inhabited by English-speaking Montrealers, who, for the most part, lived west of St. Lawrence Boulevard. Geographically it encompassed the area bounded by University Street to the east, Guy Street and Côtedes Neiges to the west, Dorchester Street to the south and Cedar and Pine Avenues to the north. Here, in what would later be labelled “the Square Mile,” flourished an English-speaking society that boasted some of Canada’s wealthiest tycoons, many of them self-made men, who, for the first time in their lives, had money to squander. And, in imitation of the great fur trading barons at the end of the eighteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth, many of them did.

The streets of the Square Mile were filled with the residences of magnates: Sir Hugh Allan (shipping), Lord Strathcona (CPR), Lord Mount Stephen (CPR), Lord Atholstan (Montreal Star), Sir William Collis Meredith (law and banking), Sir William Van Home (CPR), Sir William Macdonald (tobacco), Greenshields (law, wholesale dry goods and stockbroking), Dawes (brewing), Birks (jewellery), Morgan (department store), Ogilvie (flour), and Molson (brewing), to name but a few.28 But although every street in the Square Mile was considered fashionable (and in actual fact some of the most impressive homes, those belonging to Lords Strathcona and Shaughnessy, were located on Dorchester west of Guy) not one was more fashionable than the mile-length section of Sherbrooke Street that ran between University and Guy.

An elegant residential stretch, rivalled only by Dorchester Street, it abounded in mansions built of handsome limestone obtained from local quarries. The architecture of these varied greatly, some being formal and rather austere like Kildonan, others Scotch baronial like the “grandly artistic house” built by Sir George Drummond at the southeast corner of Sherbrooke and Metcalfe Streets. No matter what its architecture, though, every house invariably had three dining rooms: the main dining room, the children’s, and the servants’ hall. There was also a formal drawing room and a spacious conservatory, often supported by a large greenhouse which grew not only an abundance of flowers, but sometimes fruits, such as nectarines, grapes and peaches.29 Most households had a staff comprising a coachman, groom, chauffeur (after the advent of the automobile), butler, cook, kitchen maid, housemaid, tablemaid and a permanent charwoman. A few establishments had many more than nine servants.

Sherbrooke Street was the aristocratic street of Montreal before commercialization began to make itself felt in the late 1920s. Indeed, this artery of success created such an awesome impression on late Victorian observers that the authors of an article on Montreal in 1882 stated emphatically, “Sherbrooke Street is scarcely surpassed by the Fifth Avenue of New York in the magnificence of its buildings.”30

Four or five blocks east of Kildonan, on Sherbrooke Street, was one of these magnificent edifices, the massive stone residence of Sir William Van Home, a friend and business associate of Cairine’s father. In this impressive, 52-room home could be found one of the largest collections of Japanese porcelain in North America as well as a mammoth art collection, both assembled with the same spirit and energy that this huge Renaissance man had brought to the laying of the Canadian Pacific Railway’s tracks when he was in charge of the railway’s construction.

Across from the Van Home mansion, on the south side of the street, just west of Peel, at number 916, was the “young ladies’ school” where Cairine Mackay obtained her early education, for, unlike children from many other wealthy families, she was not educated by a governess and tutor at home. Known by the delightfully old world name of “Misses Symmers and Smith’s,” it frequently enjoined its pupils — who were always referred to as “young ladies” — to cultivate that most desirable of attributes, the soft, low voice of woman. It also appears that Miss Smith was fond of quoting the verse in Ecclesiastes that reads, “Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do it with thy might.” This, at any rate, was the injunction that above all others made a deep impression on Cairine Mackay because in later life whenever she was tempted to skimp on a job, she would recall these words and then strive to do her best.31

Her final school years, 1899-1902, were spent at Trafalgar Institute, which opened in 1887 in a red sandstone house on Upper Simpson Street, just a short walk from Kildonan. At this most exclusive of ladies’ finishing schools, Cairine Mackay was deeply influenced by the headmistress, Grace Fairley, a remarkable woman, who demonstrated by word and deed her firmly held conviction that “It is much better to sacrifice all in defence of country or ideals, even though one knows at the outset that there is no hope, than it is to take the easy way out.”32 This maxim, like the verse from Ecclesiastes, made a lasting impression on Cairine Mackay and became an infallible guide in the years that lay ahead.

Her firmly held principles, notwithstanding, Miss Fairley does not fit our stereotyped image of the Victorian headmistress. Far from being intimidating, she was an approachable person who stood at the head of the school stairs and personally welcomed each pupil at the start of the school day. She also expressed a great love of flowers, children and small animals and tried to inculcate in her students an understanding and appreciation of each season and its particular beauties. Moreover, where another teacher might insist on adhering to a rigid timetable and a prescribed format, this gifted classics scholar was not above encouraging her pupils to close their books and to air their thoughts on topics quite removed from the lesson at hand.

Such is the stuff of which fond school memories are made, at least for Cairine Wilson, who thirty years after graduating from her alma mater, recorded them in a tribute to Grace Fairley, who had died a few months earlier.33 Still later, beginning in the 1950s, and continuing until her death, the Senator donated a special award, named the Fairley Prize, to a member of the graduating class at Trafalgar who had made an outstanding contribution to school life. Since Cairine Wilson’s death the prize has been donated annually by the Trafalgar Old Girls’ Association “ in memory of Miss Fairley and the Hon. Senator Cairine Wilson.”34

Cairine enjoyed studying, her favourite subjects being history and mathematics. No doubt to the delight of her education-conscious father, she earned good marks, ranking second in Form IV, third in Form V and first in her graduation year, by which time the school body had grown to seventy-eight boarders and day pupils and a separate day school wing had been added to the original house.35 At Trafalgar she learned French, which would prove an invaluable asset in later years, and developed close friendships with Elsie Macfarlane McDougall, Louise Hays Grier, Winnifred Stanley Hampson and Pauline Hanson Davidson. No matter what the years would bring in the way of vicissitudes and changing circumstances, they would remain “best friends,” corresponding, telephoning each other, and exchanging gifts at Christmas and on birthdays. And when it came time to draw up her will, Cairine Wilson would remember Elsie McDougall’s children just as if they were members of her own family.36

However, although she was a good student and would probably have benefited a great deal from a university education, Cairine Mackay never went on to higher learning. Probably she, like most other women raised in the Anglo-Celtic tradition, regarded the life of the mind as essentially a male preserve. McGill could take the bold step of admitting women for the first time in 1884, but in Cairine Mackay’s circle in 1902, it was still unthinkable for a woman to enrol in a university program — unthinkable, that is, for everybody but precocious Marion Creelman Savage. Born in Toronto, she studied at the prestigious American women’s college, Bryn Mawr, Queen’s College, London, and McGill University, from which she obtained a bachelor of arts degree in 1908. It was probably while she was enrolled at McGill that she came to know Cairine Mackay who became a lifelong friend.

Although school and church were important influences in Cairine Mackay’s life, social functions and sports were not neglected. For young ladies from her set winter sports had a special attraction, and none more so than toboganning which had come into its own in the early 1880s. It was the most exciting sport in nineteenth century Montreal because nothing could equal it in speed, skiing not entering the picture until the closing years of the 1890s. To hurtle down steep hills like Ontario Avenue (now Avenue du Musée) or the daunting five-lane toboggan slide that was conveniently situated just across Sherbrooke Street from Kildonan was to ride with the wind and experience thrill after thrill. Even more exhilarating was to race down one of the gaily festooned slides that shot over the ice of the St. Lawrence River during Winter Carnival week, a week which also offered such attractions as driving in a tandem on snowy streets to swirling around the ice at a fancy dress skating ball.

Year round, on Mount Royal, there was riding, the sport that above all captured Cairine’s fancy. That she prided herself on her horsemanship and love of horses is evident in this excerpt from the one diary of hers that survives. Describing a tour that she made of the Scottish border country in 1904, she observes in her large bold hand:

On the way back [from Roslin] Janet and I managed to get box seats much to my delight. Our driver had a very jolly face & although he said little interested me very much I was very pleased when he turned to me and asked if I did not know something about horses. He said he just thought I must.37

Sewing was another great love. Indeed, she became so proficient with the needle that she taught ladies how to sew, and they in appreciation gave her a gold thimble for a wedding gift. Before long, though, sewing would take second place to knitting, the great diversion of her adult years.

In her teenage years, there were the inevitable winter season balls, some of which were staged at the sumptuous Windsor Hotel, where visiting royalty, heads of state, and celebrities, such as Lillie Langtry, usually stayed when they were in Montreal. Others, however, were held in the stately mansions of the Square Mile, one of these being Kildonan, where scores of young people attended Cairine’s own debutante party in 1905. Given her extreme shyness, it was probably a painful initiation.

The Sunday Sun, a faithful chronicler of news in the fashionable set of English-speaking Montreal, informed its readers on 5 February 1905:

During the past week things have been more or less at a social standstill, Mrs Robert Mackay’s dance being the only big private function of the week. It took place on Friday evening and everything possible was done to make it a success. The popular debutante, Miss Cairine Mackay, in whose honour the dance was given, looked exceptionally well in a yellow gown, a charming touch of colour being given by her bouquet of deep tinted roses. She received with Senator and Mrs Mackay, the latter quite recovered from her recent severe cold, looking well in black and white. The charming married daughter of the house, Mrs Robert Loring, was present as well as a large number of the younger married set. Indeed, it was quite a big dance and the rooms were taxed to their utmost capacity. The decoratitions [sic] while simple were pretty.

“The charming married daughter of the house” was, of course, warm, vivacious Anna, six years Cairine’s senior. She had married Robert Loring in the autumn of 1903, following a flurry of entertainments that included teas and dinner dances, all packed into a few short weeks “owing to the illness of Mrs Mackay.”38 After their marriage, Anna and her husband, a Boston native and an MIT graduate, installed themselves in the George Smithers house, on Sherbrooke Street, a couple of blocks west of Kildonan. With Anna’s departure from the family nest, Cairine became the only daughter still at home. And it was perhaps partly to compensate her for some of the loneliness that she undoubtedly experienced that her father gave her a trip to Europe and the United Kingdom in the summer of 1904.

Cairine embarked on her trip at the height of what the French would later call “la belle époque,” that period of remarkable stability that ran from the turn of the century until the outbreak of World War 1. The phrase itself conjures up a host of nostalgic spectacles: elegantly attired gentlemen and expensively gowned ladies walzing in ornate ballrooms to the music of Franz Lehar; women wearing long, flowing dresses and hats with artificial fruits and plumes, waists tightly corseted; bearded men sporting dark clothes and bowler hats in the winter, white linen and Panama hats in the warm weather; leisurely boating on the Seine, and throughout Western Europe generally an air of optimism and extravagance.39 Even in Britain it was a time of worldliness for three years earlier Queen Victoria had died and had been succeeded by her bearded, portly son Albert as Edward VII. With the accession of the champagne-and-fun-loving monarch to the throne, the Victorian age was over and Victorianism as a state of mind and as a mode of behaviour became a thing of the past.

In the company of her life-long friend, Elsie Macfarlane McDougall, and three other girls — Mary Clark, Janet Anderson and J. Alice Gingras —plus three chaperones, Cairine sailed from New York on 25 May on the “S.S. Ryndam,” bound for Rotterdam. After four whirlwind months on the Continent and in Britain, they sailed from Naples for Boston and the final leg of the trip to Montreal.

The diary that she kept of the trip reveals a keen appreciation of art and old world architecture, both of which are described in loving detail. Noticeably lacking, however, is any enthusiasm for the International Congress of Women that was held that June in Berlin. For Miss Hill, a tour chaperone, this Congress was the tour’s raison d' être, but for Cairine Mackay it was a boring event whose social functions and working sessions were to be avoided if at all possible. In diary entries that hint at a latent contempt for aggressive feminism, she wrote:

June 8: “Much to our disgust we were taken after breakfast to the Congress of Women from all parts of the world. Routine business was discussed and after a short time we left, Miss Hill having been elected President’s Proxy for Canada.” June 9: “Reception in honour of the delegates to the Congress of Women.” June 11: In the evening the others went to a reception given by Mrs May Wright Sewell President of the International Congress of Women, but I escaped.”40

A meeting in Berlin with Susan Brownell Anthony, the pioneer leader of the women’s suffrage movement in the United States, failed to rate a mention in the diary. Not until she had become a reluctant trailblazer herself would Cairine Mackay refer to the encounter.41

At the Old Ship Hotel, in the seaside resort of Brighton, Cairine just missed seeing Rudyard Kipling, who had left minutes earlier in his car and, in Scotland, she found herself captivated by the beauty of Sir Walter Scott’s country and intoxicated with joy, riding in a horse-drawn coach:

We reached Aberfoyle about 11:45 and after we had eaten our bread on the gallery above the entrance, where our party must have presented an amusing spectacle, we went for a short walk until the coach started. We stood for a few minutes on the bridge mentioned in Rob Roy as the one over which the Baillie and Frank Osbaldestone went. We then got on the coach and had a fine drive from Aberfoyle to Loch Katrine. The scenery was magnificent particularly near the Trossachs and I felt as if I could spend my life driving, indeed to wear a red coat and handle 4 horses was the height of my ambition. The boat Sir Walter Scott was waiting for us so as soon as the passengers were on it started across the lake, which looked beautiful shut in by the mountains, although there was no sun to lighten it. Until I saw the country, however, I had never realized the beauty of Scott’s descriptions.42

Before her marriage, Cairine Mackay made at least two trips to Europe and travelled extensively in Quebec. She also came to know St Andrewsby-the-Sea, New Brunswick, where her father built a summer home, Clibrig, in 1905, after sending his family to various watering spots on the lower St Lawrence River in previous summers. But, with one exception, the rest of Canada was by and large foreign to her. That one exception was Ottawa.

Cairine Mackay’s introduction to this raw, parochial capital came through her father, a Liberal Party stalwart and a friend of its leader, Sir Wilfrid Laurier. Robert Mackay, in fact, had been one of four affluent Liberals—the others were Newell Bate and William Hutchison of Ottawa and William Cameron Edwards of Rockland, Ontario and later Ottawa — who signed an agreement calling for the Liberal Party to purchase an Ottawa residence for its chief and then to vest the property in the names of the cosignatories as joint tenants.43 Lady Laurier later bequeathed the residence to William Lyon Mackenzie King, stating in her will, “The house having been given us by political friends of my husband, I am of the opinion that it should revert to the Liberal Party represented by its chief WLM King for the purpose of being his official residence.”44

Robert Mackay did not confine himself to supporting the party financially and to assisting in the purchase of a house for its somewhat impecunious leader. He also lobbied vigorously on behalf of defeated election candidates and operated as a de facto riding worker in Montreal, sniffing out developments of possible interest to his fellow Liberals and firing off letters bristling with wise counsel. After the election of 1896, for instance, he reported to Laurier:

I had the pleasure of meeting today Dr Innes (whom I knew before) who was the member for S. Wellington for so many years & one of your most earnest admirers and supporters while you were both in the cold shades of opposition. He was signally unfortunate in losing his reelection at this particular time, & his friends feel it would be a gracefull [sic] recognition of his services to the Liberal Party for over 40 years if the Government could see its way to present him with the Senatorship now vacant for Ontario. I make this suggestion with all due regard to the many considerations which must enter into the giving of this appointment.

I am sorry to have to trouble you so much, but I feel I would be neglectfull [sic] of my duties to our Party did I not warn you of a growing feeling of discontent among your English speaking Protestant supporters in this district. They are being threatened with the filling of any vacancies that may arise in positions now held by their class by our French Canadian friends. Needless to state that these reports come principally from our opponents, $ it will be, if justified by events, made the most of to the detriment of the Government, & I have therefore felt it right (not sharing in the feeling myself) to send you a friendly word of warning regarding any appointment to such vacancies.45

That same election of 1896 also saw Cairine’s father enter the political fray for the first time. After “accepting the call of the leading representatives of the mercantile, manufacturing, and industrial classes of Montreal,” he contested St Antoine division for the Liberals, but lost to his Conservative opponent. He did succeed, however, in reducing the adverse majority in this long-held Tory riding from 3,706 to 157.46

Four years later, he again tried his luck in St Antoine division, but once more he went down to defeat. The following year, on 21 January, just as the old Queen’s life was ebbing away, he was appointed a Liberal senator for the division of Alma in the province of Quebec. His commission as senator was the last one signed under Victoria’s reign.

Once appointed to the Senate, the family patriarch began making regular trips to Ottawa to attend sessions of parliament. He was frequently accompanied by Cairine, who, alone of the Mackay children, appears to have taken an interest in politics at an early age. Perhaps it was the long passages that her father read from the works of Gladstone, Fox, Morley and Bright to his assembled family that fired her imagination, or maybe it was the heated political discussions that, along with the comings and goings of politicians, were so much a feature of life at Kildonan. But more likely it was the magnetic presence of the tall, graceful Sir Wilfrid himself, who with his high starched collar and shock of grey-tinged chestnut hair epitomized a late Victorian prime minister. A frequent visitor to Kildonan, Sir Wilfrid would pat young Cairine’s black head and tell her that one day she would be the wife of a great politician.47 Like so many other admirers, she quickly succumbed to the prime minister’s charm and one day when she was brushing the hair of eight-year-old Edward she groaned, “ You will never make a Sir Wilfrid Laurier!”

In Ottawa, Cairine often stayed at the Laurier home, the large brick house in Ottawa’s Sandy Hill area that is now known as Laurier House. Long would she remember the happy mornings that she spent there: breakfasting with Sir Wilfrid, who taught her how to eat oatmeal in true Scottish fashion — with salt — and later watching her idol depart for his office, wearing impeccably creased striped trousers and a dignified Prince Albert coat with, no doubt, the horseshoe stickpin that was his signature in the lapel.48

Still later in the day there might be visits to the Senate Chamber, then, as now, found at the east end of the “House of Commons Building,” and to the Commons Chamber itself, a square-shaped room, located not in the extreme west of the Centre Block, as today, but in the middle of the building. Then, in the evening, there might be a social function to attend. One, in fact, stands out above all the others. This was the ball at Government House at which Cairine met her future husband.