Читать книгу Transformer: The Complete Lou Reed Story - Victor Bockris - Страница 13

Pushing the Edge

ОглавлениеSYRACUSE UNIVERSITY: 1960–62

Lou liked to play with people, tease them and push them to an edge. But if you crossed a certain line with Lou, he’d cut you right out of his life.

Allen Hyman

In order to continue their friendship, Lou and Allen Hyman had conspired to attend the same university. “In my senior year in high school Lou and I and his father drove up to Syracuse for an interview,” recalled Allen. “We didn’t speak to his father much, he was quiet. Quiet in the sense of being formal—Mr. Reed. We stayed at the Hotel Syracuse, which was then a real old hotel. There were also a bunch of other kids who were up for that with their parents. Would-be applicants to Syracuse. Lou’s father took one room and Lou and I took another. We met a bunch of kids in the hall that were going to Syracuse and we had this all-night party with these girls we met. We thought this was going to be a gas, this is terrific. The following day we both knew people who were going to Syracuse at the time who were in fraternities, and the campus was so nice, I think it was the summer, it was warm at the time, it looked so nice.”

The two boys made an agreement that if they were both accepted, they would matriculate at Syracuse. “We both got in,” said Hyman. “And the minute I got my acceptance I let them know I was going to go and I called Lou very excited and said, “I got my acceptance to Syracuse, did you?” And he said, ‘Yes.’ So I said, ‘Are you going?’ and he said, ‘No.’ And I said, ‘What do you mean, no? I thought we were going, we had an agreement.’ He said, ‘I got accepted to NYU and that’s where I’m going.’ I said, ‘Why would you want to do that, we had such a good time up there, we liked the place, I told them I was going, I thought you were going.’ He said, ‘No, I got accepted at NYU uptown and I’m going.’”

Lewis Reed, 17, 1959. ‘I don’t have a personality.’

In the fall of 1959, Lou headed off to college. Located in New York City, New York University seemed like a smart choice for a man who loved nothing more than listening to jazz at the Five Spot, the Vanguard, and other Greenwich Village clubs. But the Village was not the NYU campus Lou chose. Almost incomprehensibly, he signed up for the school’s branch located way uptown in the Bronx. NYU uptown provided Reed with neither the opportunities nor the support that he needed. Instead, Lou was left floundering in a strange and hostile environment. One of his few pleasures came from visiting the mecca of modern jazz, the Five Spot, regularly, but he didn’t always have the money to get in and often stood outside listening to Thelonious Monk, John Coltrane, and Ornette Coleman as the music drifted out to the street.

However, Lou’s main concern was not college. The Bronx campus was convenient to the Payne Whitney psychiatric clinic on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, where he was undergoing an intensive course of postshock treatments. According to Hyman, who talked to him on the phone at least once a week through the semester, Lou was having a very, very bad time. “He was in therapy three or four times a week,” Hyman recalled. “He hated NYU. He really hated it. He was going through a very difficult time and he was taking medication. He was having a lot of difficulty dealing with college and day-to-day business. He was a mess. He was going through a lot of very, very bad emotional stuff at the time and he probably had something very close to a minor breakdown.”

After two semesters, in the spring of 1960, having completed the Payne Whitney sessions although still on tranquilizers, Lou couldn’t take the NYU scene anymore.

One of the few people who encouraged Lou during his yearlong depression was his stalwart childhood friend, Allen Hyman, who now urged him to get away from his parents. Allen encouraged Lou to join him at Syracuse—a large, prestigious, private university, hundreds of miles from Freeport. In the fall of 1960, shaking off the shadows of Creedmore and the medication of Payne Whitney, Reed took Hyman’s advice and enrolled at Syracuse.

***

The coeducational university, attended by some nineteen thousand sciences and humanities students, had been established in 1870. It was located on a 640-acre campus atop a hill, in the middle of the city. Its $800 per term tuition was relatively high for a private university. Most of the students lived in sororities and fraternities and were enjoying one last four-year party before putting aside childish notions for the economic responsibilities of adulthood. There was, among the student population, a large and wealthy Jewish contingent, generally straight-arrow fraternity men and sorority women bound for careers in medicine and law. There was a small margin of artists, writers, and musicians with whom Lou would throw in his lot, enjoying, for the first time in his life, a niche in which he could find a degree of comfort. Among many other talented and successful people, the artist Jim Dine, the fashion designer Betsey Johnson, and the film producer Peter Guber all graduated in Reed’s class of 1964.

The Syracuse campus looked like the perfect set for a horror movie about college life in the early 1960s. Its buildings resembled Gothic mansions from a screenwriter’s imagination. Indeed, the scriptwriter of The Addams Family TV show of the 1960s, who attended the university at the same time as Lou, used the classically Gothic Hall of Languages as the basis for the Addams Family mansion. The surrounding four-block-square area of wooden Victorian houses, Depression-era restaurants, stores, and bars completed the college landscape. A pervasive ocher-gray paint lent a somber air to the seedy wooden houses tucked away in side streets covered, most of the time, with snow, wet leaves, or rain. The atmosphere was likely to elicit either poetic contemplation or depressive madness. It provided a perfect backdrop for the beatnik lifestyle.

The surrounding city of Syracuse presented no less smashed a landscape. The manufacturing town got dumped with snow seven months of the year, and heavy bouts of rain the rest of the time. Only during the summer, when most of the students had scattered to their homes on Long Island or New Jersey, did the city receive warmth and sunshine. A thriving industrial metropolis popularly known as the Salt City, also specializing in metals and electrical machinery, it was two hundred miles northwest of Freeport, forty miles south of Lake Ontario on the Canadian border, and five miles southwest of Oneida Lake. Syracuse was aggressively conservative and religious, but at the time of Reed’s arrival it was fast turning into the academic hub of the Empire State. The city proudly supported its prestigious university, whose popular football team, the Orangemen, was undefeated during Lou’s four years, and its residents turned out in great numbers for athletic events. Despite high academic standards, Syracuse was still primarily seen as a football school. “Where the vale of Onondaga / Meets the eastern sky / Proudly stands our Alma Mater / On her hilltop high” ran the opening verse of the school song, a ditty Lewis, as many of his friends called him, would not forget.

As a freshman, Lou was assigned to the far southwestern corner of the North Campus in Sadler Hall, a plain, boxlike dormitory resembling a prison. However, much of his time was spent in the splendid, gray-stone Hall of Languages, which overlooked University Avenue and University Place at the north end of campus and housed the English, history, and philosophy departments.

Syracuse University had excellent faculty and academic courses. Though Lou may have sleepwalked through much of the curriculum, he threw himself into the music, philosophy, and literature studies in which he excelled. In music appreciation, theory, and composition classes, Lou soaked up everything, even opera. First, Lou tried his hand at journalism, but he dropped that after a week when the teacher told him his opinions were irrelevant. However, Lou quickly immersed himself in philosophy. He devoured the existentialists, obsessed over the tortuous dialectics of Hegel, and embraced the Fear and Trembling of Kierkegaard. “I was very into Hegel, Sartre, Kierkegaard,” Reed recalled. “After you finish reading Kierkegaard, you feel like something horrible has happened to you—fear and nothing. That’s where I was coming from.” He also loved Krafft-Ebing and the writing of the beat generation, particularly Kerouac, Burroughs, and Ginsberg. To complete his freshman image, he took imagistic inspiration from the brash, tortured figures of James Dean, Marlon Brando, and, most of all, Lenny Bruce.

To his advantage, Reed already had the perfect agent to introduce him to the university, the smooth operator and prince of good times Allen Hyman, now entering his sophomore year. Another pampered suburban kid who drove both a Cadillac and Jaguar, Allen was generous, full of good humor, and sharp-witted. Furthermore, he genuinely appreciated Lou and was willing to put up with a lot of flak to remain his friend. Hyman was well connected with the straight fraternity set and eager to introduce Lewis to his world.

However, a highly uncomfortable introduction came about when Allen tried to get Lou to rush his fraternity, Sigma Alpha Mu (aka the Sammies). “Hazing was a really horrendous experience and most people were very intimidated by it,” recalled Hyman. Inductees were forced to drink themselves into oblivion and were often humiliated physically, sexually, and mentally by the fraternity brothers. When Allen told Lou stories about what he went through to join a fraternity, Lou shot him a hard look, snapping, “What are you into—masochism?”

“He had said that he didn’t want anything to do with it and that it was fascistic and disgusting,” Hyman recalled, “and he couldn’t believe anybody would be willing to go through hazing without killing the person who was hazing them.” However, typically perversely, Reed agreed to attend a rush session.

From the outset it was clear that he intended to make a strong impression. Reed came to the socializer in a suit three sizes too small and covered in dirt. It was a radical departure from the blue blazer, smart tie, and neatly combed hair of the other rushees. Allen immediately realized how much Lou was getting off on being outrageous. When one of the brothers criticized Lou’s appearance, Reed riposted, “Fuck you!” and his fraternity career came to an abrupt end. Hyman was asked to escort his friend out immediately. Walking Lou back to his dorm, a chagrined Allen hung his head regretfully, but Lou, far from being despondent, appeared exhilarated by the event. “I guess this isn’t for you,” Allen said.

“Yeah, that’s right,” Lou replied. “I told you I wouldn’t get along with those assholes. How can you live there?”

Another freshman trial that Lou failed was with the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps. As part of his freshman course requirements, he had to choose between physical education and ROTC. (In those days it was common to join ROTC in order to be able to go into the army as an officer and a gentleman.) Claiming that he would surely break his neck in phys ed or else kill somebody in ROTC, Lou attempted to evade either requirement, but in the end grudgingly signed up for the latter. ROTC consisted of two classes a week about how to be a soldier and possibly a leader. However, Lou’s military experience was almost a short-lived as his fraternity stint. Just weeks into the semester, when he flatly refused a direct order from his officer, he was unceremoniously booted out.

But Reed managed to make an impact on his freshman year with his very own radio show. Employing a considerable boyish charm to overcome the severe doubts of program director Katharine Griffin, during his first semester Lou hustled his way onto the Syracuse University radio station, WAER FM, with a jazz program called Excursions on a Wobbly Rail (named for a wicked Cecil Taylor piece that was used as his introductory theme). The classical, conservative station, Radio House, was situated in a World War II Quonset hut tucked away behind Carnegie Library. Freezing his balls off through many icy Syracuse evenings, hunched over his ancient machinery like some WWII underground resistance fighter for two hours, three nights a week, Lou blasted a mélange of his favorite sounds by the avant-garde leaders of the Free Jazz movement Ornette Coleman and Don Cherry, the doo-wopping Dion, and the sexually charged Hank Ballard, James Brown and the Marvelettes. The mixture presented the essence of Lou Reed. “I was a very big fan of Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor, Archie Shepp,” he recalled. “Then James Brown, the doo-wop groups, and rockabilly. Put it all together and you end up with me.”

Unfortunately, the Reedian canon was not appreciated by the station’s staff, and numerous faculty members, including the dean of men, lodged complaints about the—to them—hideous, unintelligible cacophony that was Reed’s program. And the authorities’ reaction was not Lou’s only problem. Disguising his voice, Allen Hyman would often call Lou at the station and harass him with ridiculous requests. On one occasion, “I asked him to play something he hated and I knew he would never play,” Allen recalled. “He said, ‘No, I’m not going to play that, forget it.’ So I said, ‘Listen, if you don’t play this, I’m gonna fucking have you killed. I’ll wait for you myself and I’m gonna kill you!’ And, thinking it was some lunatic, Lou got scared. Then I called him back and told him it was me and he screamed at me, saying that if I ever did that again he’d never speak to me.”

As it turned out, Allen’s pranks didn’t last long enough to lose him Lou’s friendship because before long Griffin, ever vigilant in her duties as WAER’s program director, concluded that “Excursions on a Wobbly Rail was a really weird jazz show that sounded like some new kind of noise. It was just too weird and cutting edge.” Before the end of the semester, she unceremoniously dumped it from the air, causing Lou considerable anguish.

In retrospect, Griffin and her contemporaries realized that Reed was simply ahead of his time. “Most of us who were in power on campus were children of the fifties,” she explained. “Kids in those days wore chinos and madras shirts, a clean-cut Kingston Trio kind of thing. Lou looked more like what a rock person from later in the sixties would look like. Lou was presaging the sixties and seventies and we just weren’t ready for it. He was right on the cusp of two generations. A little too far ahead to be admired in the fifties.”

During his first year at Syracuse, the scholarly Griffin concluded, “It was just Lou versus everybody else.”

Lou quickly defined himself as an oddball loner. Eschewing all organizations, he was creating an image that would in time become widely acknowledged as the essence of the hip New York underground man. Lou was a year older than most freshmen and fully grown. Measuring five feet eight inches (although he claimed to be five feet ten) he was a little chubby and some way yet from the Lou Reed of “Heroin.” He wore loafers, jeans, and T-shirts, tending, if anything, to be a little sloppier than the majority of men at school, who wore the fraternity uniform of jacket and tie. His hair was a trifle longer than theirs. Otherwise, he would not have been noticed in a crowd. His looks tended toward the cute, boyish, curly haired, shy, gum-chewing. He had a small scar under his right eye. His most unusual feature was his fingers. Short and strong, they broadened into stubby, almost blocklike fingertips, making them perfect tools for the guitar.

Lou had already formed his ambition to be a rock-and-roller and a writer. The university’s rich music scene consisted of an eclectic mix of talents like Garland Jeffreys, a future singer-songwriter and Reed acolyte two years younger than Lou; Nelson Slater, for whom Lou would later produce an album; Felix Cavaliere, the future leader of the Young Rascals; Mike Esposito, who would form the Blues Magoos and the Blues Project; and Peter Stampfel, an early member of the Holy Modal Rounders, who would become a pioneer of folk rock. While colleges in New York and Boston produced folksingers in the style of Bob Dylan, Syracuse created a bunch of proto-punk rockers.

Most importantly for Lou musically, it was at Syracuse he met fellow guitarist Sterling Morrison, a resident of Bayport, Long Island, who had a similar background. Just after Lou got kicked out of ROTC, Sterling, who was never actually enrolled at Syracuse but spent a lot of time there hanging out and sitting in on some classes, was visiting another student, Jim Tucker, who occupied the room below Lou’s. Gazing out Tucker’s window at the ROTC cadets marching up and down the quad one afternoon, Morrison suddenly heard “earsplitting bagpipe music” wail from someone’s hi-fi. After that, the same person “cranked up his guitar and gave a few shrieking blasts on that.” Excited, Morrison realized, “Oh, there’s a guitar player upstairs,” and prevailed on Tucker for an introduction.

When they met at 3 a.m. the following morning, Lou and Sterling discovered they shared a love for black music and rock and roll. They also loved Ike and Tina Turner. “Nobody even knew who they were then,” Morrison recalled. “Syracuse was very, very straight. There was a one percent lunatic fringe.”

Luckily, the drama, poetry, art, and literary scenes were just as alive as the music scene for that one percent fringe. Soon Lou was spending the majority of his time playing guitar, reading and writing, or engaging in long rap sessions with like-minded students. Many of Lou’s conversations about philosophy and literature took place in the bars and coffee shops he and his friends began to call their own. Each restaurant had its social affiliations. Lou’s crowd set up camp at the Savoy Coffee shop run by a lovable old character, Gus Joseph, who could have walked right out of a Happy Days TV episode. At night, they drank at the Orange Bar, frequented predominantly by intellectual students. According to Lou, he took two steps out of school and there was the bar. “It was the world of Kant and Kierkegaard and metaphysical polemics that lasted well into the night,” he remembered. “I often went to drink alone to that week’s lost everything.” He had become accustomed to taking prescription drugs and smoking pot, but Lou was not yet a heavy user of illegal substances. At the most he might have a Scotch and a beer.

At Syracuse, Lou presented himself as a tortured, introspective, romantic poet. Following the dictate that the first step to becoming a poet is to look and act like one, Lou liked, for example, to give the impression that he was unwashed, but that wasn’t true. According to one friend, “He wasn’t about to go out unless he took a shower first.” As far as his costume was concerned, he was still stuck somewhere between the suburban teenager in loafers and button-down shirts and the rumpled dungarees and work shirts of the Kerouac rebel. Observers remembered him as more chubby and cherubic than thin and ascetic. In fact, he didn’t dress unusually at all. If anything, he dressed poorly, wearing the same pair of dirty jeans for months. As for his demeanor, Lou copped the uptight approach of the young Rimbaud. He was just beginning to swing with the legend of his electroshock treatments, turtleneck sweaters, and the whole James Dean inspired “I’ve suffered so much everything looks upside down” routine.

According to one student who occasionally jammed with him, “Part of his aura was that he was a psychologically troubled person who in his youth had had electroshock treatments which clearly had an effect on him. He used that as part of his persona. Where the reality and the fantasy of what he was crossed, who knew.” For a sarcastic kid who had grown up with buck teeth, braces, and a nerd’s wardrobe, Lou wasn’t doing badly turning himself into the image of a totally perverse psycho. However, whatever he did with his wardrobe and his attitude to make himself hip, there was one nightmarish detail about his looks that seemed always to overwhelm him—his hair. His frizzy helmet had plagued him since he’d started looking into the mirror with intense interest in his twelfth year. What stared back at him throughout his adolescence was a Jewish version of Alfred E. Neumann.

Since America had been a largely anti-Semitic nation, the Jewish “Afro” was seen as geekishly ethnic. In the early sixties, Bob Dylan would single-handedly change the image of what a hip young boy could look like. Though the film industry and media characters like Allen Ginsberg had begun to turn the whole Jewish male persona into something ultra-chic, nobody came close to having the pervasive influence of Bob Dylan. As Ginsberg explained to his biographer Barry Miles, when Dylan appeared, particularly in his 1965 Bringing It All Back Home incarnation, he made the hooked nose and frizzy hair the very emblem of the hip, intellectual avant-garde. By the time Lou got to college, however, and started to resculpt himself into the Lou Reed who would emerge in 1966 as the closest competition to Dylan for the hippest rock star in the world, he was ready to do something about his hair. At Syracuse he discovered a hair-treatment place in the black neighborhood and on several occasions had his hair straightened.

Just like his British counterparts Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones or John Lennon of the Beatles, Lou rejected the lifestyle that came before the bomb and was remaking himself out of a combination of his favorite stars. Such self-creation was not difficult for Lou, who often claimed he had as many as eight personalities. He now clothed these personalities in the costumes and attitudes of a cast of media characters who were as important to his image as the first creative friends he would hook up with at Syracuse.

First among them was Lenny Bruce. Though damned by his legal problems to a horrible fate, Bruce was at the apogee of his career. In the eyes of the public he was the hippest, fastest-talking American poet and philosopher around. Bruce spiked his act—a kind of Will Rogers on fast-forward—by injections of pure methamphetamine hydrochloride, which would in time become Lou’s own drug of choice. Many of Reed’s mannerisms, his hand gestures, the way he answered the phone as if he was asleep, the rhythm of his speech, came directly from Bruce.

As for the rest of Lou’s media idols, you only have to look at a panel of head shots of the stars of the era to see what Lou would take in time from Frank Sinatra, Jerry Lewis in The Bellboy, Montgomery Clift, and William Burroughs, to name but a few of the more obvious ones. In fact, one of Lou’s most attractive characteristics was the way he appreciated and celebrated his heroes. He was always trying to get Hyman, for example, a straight law student whose path would lead in a direction diametrically opposite to Lou’s, to read Kerouac and then rap with him about it. Lou loved turning people on to the new sounds, the new scenes, and the new people.

A lot of the artistic kids who went to Syracuse look back upon it with disdain as a football school dominated by the “fucking” Orangemen. In fact, in that watershed period between the end of McCarthyism and the death of Kennedy, a new permissiveness swept through colleges across the country. Syracuse contained and nurtured a lot of different environments. Certainly the fraternity environment still dominated the American campus, and the majority of male and female students still aligned themselves with a fraternity or sorority in sheeplike fashion. There was, however, a vital cultural split between the Jewish and the non-Jewish fraternities. The Jewish fraternities were for the most part hipper, more receptive to the new culture and more open to alternative ways of living. Despite completely rejecting Sigma Alpha Mu and attaching himself primarily to the arty intellectual crowd, some of whom had apartments off campus, Lou maintained a loyal friendship with Hyman and was, in fact, adopted as something of a mascot by the Sammies as their resident oddball. They weren’t about to miss out completely on a character who had already, in the first half of his freshman year, carved out an image for himself as tempestuous and evil. In fact, Jewish fraternities in colleges across America would provide some of the most receptive of Lou Reed’s audiences throughout his career.

The rules that governed a freshman’s life at Syracuse were greatly to the advantage of the male students. Whereas the girls in the dorm atop Mount Olympus were locked in at 9 p.m., and any girl who dared break curfew was subject to expulsion, the boys, who had no curfew, were able to use the night to live a whole other life, exploring the town, drinking in the Orange or in frat houses and getting up to all sorts of mischief. Naturally Lou, who had developed the habit of staying up most of the night reading, writing, and playing music, lost no time exploring his new home. He quickly discovered the neighboring black ghetto where at least one club, the 800, presented funky jazz and R&B as well as a whole culture, centered around drugs, music, and danger, that appealed to the explorer of the dark side in Reed.

Lou’s first college girlfriend was Judy Abdullah, and he called her The Arab. It may be that she was of more interest to him as an exotic object than as a person. Judy revealed an interesting quirk in Lou’s sexuality. He was turned on by big women. Judy Abdullah was twice his size. She was a sensual woman and they apparently had a good time in bed, but at least one acquaintance added a shade to Reed’s personality profile when she pointed out that his attraction to big women offered both a challenge and an escape route. Lou could take the attitude that he had no responsibility to be serious about her or even try to satisfy her.

The relationship petered out before the end of the year. Lou, who persisted in not wasting time with dates and always coming on obnoxiously, was mean to Judy, and when they broke up, she was pissed off at him for good reason. Still, they remained acquaintances and Lou saw her occasionally throughout his college years.

By the end of his first year at Syracuse, according to one of the Sammies, “Lou’s uniqueness and stubbornness made him different from anyone I had ever known. He marched to his own drum. He was for doing things for people, but his way. He would never dress or act in a way so that people would accept him. Lou had an unbelievably wry, caustic sense of humor and loved funny things. He played off people. He would often act in a confrontational manner. He wanted to be different. Lou was a funny guy in an extremely dry, witty sense. Certainly not the type of comedian that would make you laugh at him. He wasn’t making fun of things but seeing the humor in things—the banal and the normal. There was an undercurrent of saneness in everything he did. He was screwed up, but that was schizophrenia too.”

***

What Lou Reed needed most was to find a coconspirator, an equal off whom he could bounce his ideas and behavior and receive inspiration in return. Almost miraculously, he found such a person in what would become the second golden period of his life (the first being his discovery of rock and roll). Lou’s first great soul mate, mirror, and collaborator, whom he roomed with in his sophomore year, was the brilliant, eccentric, talented, but tortured and doomed Lincoln Swados. Swados came from an upwardly mobile, middle-class, and, by all accounts, outstandingly empathetic Jewish family from upstate New York. Like Reed, he had a little sister called Elizabeth, upon whom he doted (and to some extent, like Lou, identified with). The two students fell into each other’s arms like lost inmates of some Siberian prison of the soul who finally discover after years of isolated exile a fellow voyager. To make matters perfect from Lou’s point of view, Lincoln was an aspiring writer (working on an endless Dostoyevskian novel); his favorite singer was Frank Sinatra; Lincoln’s side of the room was covered in more crap than Lou’s; and—this was the clincher—Swados was agoraphobic. He spent most of his time holed up in their basement room either hunkered over a battered desk or playing Frank Sinatra records and rapping with Lou. Whenever Lou needed a receiver for one of his new songs, poems, or stories, Lincoln was always there. Their relationship was the first of many constructive collaborations in Lou’s life.

One of Lou’s strongest personalities was the controlling figure who always needed to be the center of attention and the most outstanding person in the room. Here again Lincoln was his perfect match, for if Lou ever worried that he might not yet possess the hippest look in the world, Lincoln presented no threat. He was usually togged out in a pair of pants that ended somewhere above his ankles and were belted in the middle of his chest. His customary short-sleeve shirt invariably clashed with the pants. A pair of bugged-out eyes that made Caryl Chessman in the electric chair look like a junkie on the nod stared out of a cadaverous face capped by a head of dirty, disheveled blondish hair. Lincoln’s body was as much of a mess as was his mind. He rarely bathed or brushed his teeth and at times emanated an odor that obviated any close physical relationships. The whole ensemble was tied together by a disembodied smile that clearly indicated, at least to somebody of Lou’s perceptiveness, just how far out in space Lincoln really was most of the time.

Their basement room was furnished like some barren writer’s cell out of Franz Kafka’s imagination. The two black iron bedsteads, identical desks, and battered chairs ensconced upon a green concrete floor and lit by a harsh bare lightbulb could not have better symbolized both the despair and ambition at the heart of their twin souls. They both despised the world of their parents from which they had at least temporarily escaped. Both were intent upon destroying it and all of its values with some of the most vitriolic, driven pages since Burroughs spat Naked Lunch out of his battered typewriter in Tangier. The room became their arsenal, their headquarters, their cave of knowledge and learning, and the engine of their voyage into the unknown. In time, Lou would rip off Lincoln’s entire repertoire of attitudes, gestures, and habits. Lou later confessed, “I’m always studying people that I know, and then when I think I’ve got them worked, I go away and write a song about them. When I sing the song, I become them. It’s for that reason that I’m kind of empty when I’m not doing anything. I don’t have a personality of my own, I just pick up other people’s.”

Having met his male counterpart, Lou now needed, in order to pull out the male and female sides warring within him, a female companion. Within a week of settling in with Swados, Lou saw her riding down the university’s main drag, Marshall Street, in the front seat of a car driven by a blond football player who belonged to the other Jewish fraternity on campus and recognized Reed as their local holy fool. Thinking to amuse his date, a scintillatingly beautiful freshman from the Midwest named Shelley Albin, he pulled over, laughing, and said, “Here’s Lou! He’s very shocking and evil!” making, as it turned out for him, the dreadful mistake of offering “the lunatic” a ride.

Although in no way as twisted and bent as Lincoln Swados, Shelley was as perfect a match for Lou as his roommate was. Born in Wisconsin, where she had lived the frustrated life of a beatnik tomboy, Shelley had elected Syracuse because it was the only university her parents would let her attend. In preparation for the big move away from home, Shelley, along with a childhood girlfriend, had come to Syracuse fully intending to mend her ways and acquiesce to the college and culture’s coed requirements. Discarding the jeans and work shirts she wore at home, she donned instead the below-the-knee skirt, tasteful blouse, and string of pearls seen on girls in every yearbook photo of the period. When Lou hopped into the backseat eager to make her acquaintance, Shelley was squirming with the discomfort of the demure uniform as well as her dorky date’s running commentary.

She vividly recalled Lou’s skinny hips, baby face, give-away eyes, and knew “we were going to go out as soon as he got into the car.” She also knew she was making a momentous decision and that Lou was going to be trouble, but that it certainly wasn’t going to be boring. “It was such a relief to see Lou, who was to me a normal person. And I was intrigued by the evil shit.”

The feeling was clearly mutual. As soon as the couple let Lou off in front of his dorm, Reed sprinted into their room and breathlessly told Swados about the most beautiful girl in the world he had just met, and his plans to call her immediately.

Lincoln had a strangely paternal side that would often appear at inappropriate moments. Seeing his role as steering Lou through his emotional mood swings, Swados immediately put the kibosh on Reed’s notion of seducing Shelley by informing him that this would be out of the question since he, Lincoln, had already spotted the pretty coed and, despite not yet having met her, was claiming her as his own.

Lou, for his part, saw his role in the relationship as primarily to calm the highly strung, hyperactive Swados. Reasoning that the nerdy Lincoln, who had been unable to get a single date during the freshman year, would only be wounded by the rejection he was certain to get from Shelley, Lou wasted no time in cutting his friend off at the pass by calling Shelley at her dorm within the hour and arranging an immediate date. That way, Lou told himself, he would soon be able to give Swados the pleasure of her company.

Shelley Albin would not only become Lou Reed’s girlfriend through his sophomore and junior years—“my mountaintop, my peak,” as he would later describe her—but would remain for many years thereafter his muse. “Lou and I connected when we were too young to really put it into words,” Shelley said. “There was some innate connection there that was very strong. I knew him before everything was covered up. My strongest image of Lou is always as a Byronesque character, a very sweet young man. He was interesting, he wasn’t one of the bland, robotic people, he had a wonderful poetic nature. Basically, Lou was a puffball, he was a sweetie.” For all of Lou’s eccentricities, Shelley found him “very straight. He was very coordinated, a good dancer, and he could play a good game of tennis. His criteria for life were equally straight. He was a fifties guy, the husband of the house, the God. He wanted a woman who was the end-all Barbie and would make bacon when he wanted bacon. I was very submissive and naive and that’s what appealed to him.”

But Lou also had his “crazy” side, which he played to the hilt. Like many bright kids who have just discovered Kierkegaard and Camus, he was the classic, arty bad boy. Alternating between straight and scary, Lou reveled in both. “There was a part of Lou that was forever fifteen, and a part of him that was a hundred,” Shelley fondly recalled. Fortunately for Lou, she embraced both parts equally. And going out with Lou gave Shelley the jolt she needed to throw off her skirt and pearls for jeans and let her perm return to her natural long, straight hair. Seeing her metamorphosis, the boy Shelley had left so brazenly for Lou was soon chiding her, “You went to the dogs and became a beatnik. Lou ruined you!” In fact, Shelley, an art student, had simply reverted to being herself. But she enjoyed the taunt, knowing how much Lou liked it when people accused him of corrupting her and enjoyed the notoriety it won him. Shelley was also astonishingly beautiful, and to this day, Lou’s Syracuse teachers and friends remember above all else that Lou Reed had an “outrageously gorgeous girlfriend who was also very, very nice.”

Shelley Albin had a unique face. Looked at straight on, what struck you first were her eyes. An inner light glimmered through them. Her nose was straight and perfect. Her jawline and chin were so finely sculpted they became the subject of many an art student at Syracuse. It was an open and closed face. Her mouth said yes. Yet her eyes had a Modigliani/Madonna quality that bayed, you keep your distance. Her light brown hair reflected in her pale cream skin gave it at times, a reddish tint. At five feet seven inches and weighing 115 pounds, she was close enough in size to Lou to wear his clothes.

“We were inseparable from the moment we met,” Shelley recalled. “We were always literally wrapped up in each other like a pretzel.” Soon Shelley and Lou could be seen at the Savoy, making out in public for hours at a time: “He was a great kisser and well coordinated. I always thought of him as a master of the slow dance. When we met, it was like long-lost friends.” For both of them it was their first real love affair. They quickly discovered that they could relate across the boards. They had a great sexual relationship. They played basketball and tennis together. When Lou wrote a poem or a story, Shelley found herself doing a drawing or a painting that perfectly illustrated it. She had been sent to a psychiatrist in her teens for refusing to speak to her father for three years. Lou wrote “I’ll Be Your Mirror” two years later about Shelley. And Shelley was Lou’s mirror. Just as he had rushed a fraternity, she, much to his delight, rushed a sorority and then told them to go fuck themselves an hour after she got accepted.

“His appeal was as a very sexy, intricate and convoluted boy/man,” Shelley said. “It was the combination of private gentle lover and romantic and strong, driven thug. He was, however, a little too strong, a dangerous little boy you can’t trust who will turn on you and is much stronger than you think. He had the strength of a man. You really couldn’t win. You had to catch him by surprise if you wanted to deck him.

“The electroshock treatments were very fresh in his mind when we met. He immediately established that he was erratic, undependable, and dangerous, and that he was going to control any situation by making everyone around him nervous. It was the ultimate game of chicken. But I could play Lou’s game too, that’s why we got along so well.

“What appealed to me about Lou was that he always pushed the edge. That’s what really attracted me to him. I was submissive to Lou as part of my gift to him, but he wasn’t controlling me. If you look back at who’s got the power in the relationship, it will turn out that it wasn’t him.”

Whereas the entrance of a stunning female often offsets the male bonding between collaborators, in the tradition of the beats established by Kerouac and his friend Neal Cassady, Lou correctly presumed that Shelley would enhance, rather than break up, his collaboration with Lincoln. In fact, it became such a close relationship that Lou would occasionally suggest, only half-jokingly, that Shelley should spend some time in bed with Lincoln. Their relationship mirrored that of the famous trio at the core of their generation’s favorite film, Rebel Without a Cause, with Lou as James Dean, Shelley as Natalie Wood, and Lincoln as the doomed Sal Mineo.

Lou presented Lincoln to Shelley as an important but fragile figure who needed to be nurtured. Lincoln was homely, but Shelley’s vision of him in motion was “like Fred Astaire, Lincoln was debonair and he would spin a wonderful tale and I think Lou could see this fascination. Lou felt very responsible and protective toward Lincoln because nobody would see Lincoln and we liked Lincoln.” The first thing Lou said to Shelley was, “Lincoln wants you, and if I were a really good guy, I should give you to Lincoln because I can get anybody and Lincoln can’t. Lincoln loves you, but I’m not going to give you to him because I want you.” Shelley realized that many of Lou’s ways of being charming and his gestures were taken straight from Lincoln. “A lot of what I really loved about Lou was Lincoln, who was in many ways like Jiminy Cricket standing on Lou’s shoulder, whispering words into his ear. They were going to take care of me and straighten me out and educate me.”

The most important thing about Lincoln and Shelley was their understanding and embracing of Lou’s talent and personality. If Lincoln was a flat mirror for Lou, Shelley was multidimensional, reflecting Lou’s many sides. Perceptive and intuitive, she understood that Lou appreciated events on many different levels and often saw things others didn’t. For the first time in his life Lou found two people to whom he could actually open up without fear of being ridiculed or taken for a ride. For a person who depended so much on others to complete him, they were irreplaceable allies.

Initially, Lou’s first love affair was idyllic. Lou rarely arose before noon, since he stayed up all night. He and Shelley would sometimes meet in the snow at 6 a.m. at the bottom of the steps leading to the women’s dorm. Or else in the early afternoon she would take the twenty-minute hike from the women’s dorm to Lou and Lincoln’s quarters. Like all coeds on campus, she was forbidden to enter a men’s dorm on threat of expulsion, so she would merely tap on their basement window and wait for Lou to appear. When he did, he would gaze up at one of his favorite views of his lover’s face smiling down at him with her long hair and a scarf hanging down. “I liked looking in on their pit,” she recalled. “It was truly a netherworld. I liked being outside. I liked my freedom. And Lou liked that I had to go back to the dorm every night.” From there, the threesome would repair to a booth at the Savoy where they would be joined by art student Karl Stoecker—a close friend of Shelley’s—and English major Peter Locke, a friend of Lou’s to this day, along with Jim Tucker, Sterling Morrison, and a host of others, to commence an all-day session of writing, talking, making out, guitar playing, and drawing. Lou was concentrating on playing his acoustic guitar and writing folk songs. The rest of the time was spent napping, with an occasional sortie to a class. When the threesome got restless at the Savoy, they might repair to the quaint Corner Bookstore, just half a block away, or the Orange Bar. But they always came back to home base at the Savoy, and to the avuncular owner, Gus Joseph, who saw kids come and go for fifty years, but remembered Lou as being special.

***

Lou was so enamored of Shelley that in the fall of 1961 he decided to bring her home to Freeport for the Christmas/Hanukkah holidays. Considering the extent to which Lou based his rebellious posture on the theme of his difficult childhood, Shelley was fully aware of how hard it would be for Lou to take her to his parents’ home. She remembered him thinking that he would score points with his parents: “It was sort of subtle. He was going to show his father that he was okay. He knew that they would like me. And I suspect in some ways he still wanted to please his parents and he wanted to bring home somebody that he could bring home.”

Much to her surprise, Lou’s parents welcomed her to their Freeport home with open arms, making her feel comfortable and accepted. Lou had given her the definite impression that his mother did not love him, but to Shelley, Toby Reed was a warm and wonderful woman, anything but selfish. And Sidney Reed, described by Lou as a stern disciplinarian, seemed equally loving. They appeared to be the exact opposite of the way Lou had portrayed them. In her impression, Mr. Reed “would have walked over the coals for Lou.”

At the same time Shelley realized that Lou was just like them. He not only looked like them, but possessed all their best qualities. However, when she made the mistake of communicating her positive reaction, commenting on the wonderful twinkle in Mr. Reed’s eyes and noting how similar his dry sense of humor was to Lou’s, her boyfriend snapped, “Don’t you know they’re killers?!”

Given their kind, gracious, outgoing manner, the Reeds were sitting ducks for Lou’s brand of torture. He would usually begin by embracing the rogue cousin in the Reed family called Judy. As soon he got home, Lou would enthusiastically inquire after her activities and prattle on about how he wanted to emulate her more than anyone else in the family, often reducing his mother to tears. Next, Lou would make a bid to monopolize the attentions of thirteen-year-old Elizabeth. Confiding to her his innermost thoughts, he would make a big point of excluding his parents from the powwow. “She was cute,” thought Shelley, “she looked just like Lou. So did his mother and father. They all looked exactly like him. It was hysterical. Lou was very protective of her. And she was so sweet. She didn’t have that much of a personality, but she was not unanimated.” Every action aimed to cut his parents out of his life, while keeping them prisoners in it. Meanwhile, like every college kid home on vacation, Lou managed to extract from them all the money he could, and the freedom to come and go as if the house were a hotel. As soon as everybody at 35 Oakfield Avenue was in position ready to do exactly as he wanted, Lou began to enjoy himself.

In fact, so extreme was the situation that, on this first visit, Toby Reed, looking upon her as the perfect daughter-in-law, took Shelley into her confidence. “They were very nervous about what was he bringing home,” she remembered. “So they really took it as a sign that, ‘Oh, God, maybe he was okay.’ We recognized with each other, she and I, that we both really liked him and we both loved him.” Mrs. Reed filled her in on Lou’s troublesome side and tried to find out what Lou was saying about his parents. Shelley got the impression that the Reeds bore no malice toward Lou, but just wanted the best for him. Mrs. Reed seemed completely puzzled as to how Lou had gotten on the track of hating and blaming them. Pondering the strange state of affairs unfolding behind the facade of the Reeds’ attractive home, Shelley drew two conclusions. On the one hand, since his family seemed quite normal and had no apparent problems, Lou was moved to create psychodrama in order to fuel his writing. On the other hand, Lou really did crave his parents’ approval. He was immensely troubled by their refusal to recognize his talent and needed to break away from their restricted life. One point of Lou’s frustration was the feeling that his father was a wimp who gave over control of his life to his wife. This both horrified and fascinated Lou, who was a dyed-in-the-wool male supremacist. Lou was secretly proud of his father and wanted more than anything else for the old man to stand up for himself. But Lou simply could not stand the thought of sharing the former beauty queen’s attention with his father.

After spending a wonderful, if at times tense, week in the Reed household, Shelley put together the puzzle. In a war of wits that had been going on for years, Lou went on the offensive as soon as he stepped through the portals of his home. Attempting by any means necessary to horrify and paralyze his loving parents, Lou had learned to control them by threatening to explode at any moment with some vicious remark or irrational act that would shatter their carefully developed harmony. For example, one night Mr. Reed gave Lou the keys to the family car, a Ford Fairlane, and some money to take Shelley out to dinner in New York. However, such an exchange between father and son could not pass without conflict straight out of a cartoon. As Lou was heading for the door with Shelley, Sid had to observe that if he were going to the city, he might, under the circumstances, put on a clean shirt. Instantly spinning into a vortex of anger that made Sid feel like a cockroach, Lou threw an acerbic verbal dart at his mother before slamming out the door.

On the way into New York he almost killed himself and Shelley by driving carelessly and with little awareness of his surroundings. “I remember him taking this little flower from the Midwest to the big city,” Shelley said. “Chinatown. We drove in a hair-raising ride I’ll never forget in my whole life. Lou showed me how to hang out on the heating grate of the Village Gate so you could hear the music and stay warm.”

His parents, she realized, “had no sense of what was really in his mind, and they were very upset and frightened by what awful things he was thinking. He must have been really miserable, how scary.” As a result, in order to obviate any disturbance, Lou’s tense and nervous family attended to his every need just as if he were the perennial prodigal son. The only person in the house who received any regular affection from Lou was his little sister, Elizabeth, who had always doted on Lou and thought he was the best.

However, at least for the time being, Lou’s introduction of Shelley into their lives caused his parents unexpected joy. Ecstatic that his son had brought home a clean, white, beautiful Jewish girl, Mr. Reed increased Lou’s allowance.

If he had had any idea of the life Lou and Shelley were leading at Syracuse, he would probably have acted in the reverse. As the year wore on, sex, drugs, rock and roll, and their influences began to play a bigger role in both their lives, although Shelley did not take drugs. Already a regular pot smoker, Lou dropped acid for the first time and started experimenting with peyote. Taking drugs was not the norm on college campuses in 1961. Though pot was showing up more regularly in fraternities, and a few adventurous students were taking LSD, most students were clean-cut products of the 1950s, preparing for jobs as accountants, lawyers, doctors, and teachers. To them, Lou’s habits and demeanor were extreme. And now, not only was Lou taking drugs, he began selling them to the fraternity boys. Lou kept a stash of pot in a grocery bag in the dorm room of a female friend. Whenever he had a customer, he’d send Shelley to go get it.

Lou was by now on his way to becoming an omnivorous drug user and, apart from taking acid and peyote, would at times buy a codeine-laced cough syrup called turpenhydrate. Lou was stoned a lot of the time. “He liked me to be there when he was high,” Shelley remembered. “He used to say, ‘If I don’t feel good, you’ll take care of me.’ Mostly he took drugs to numb himself or get relief, to take a break from his brain.”

Meanwhile, having presented himself as a born-again heterosexual, Lou now wasted no time in making another shocking move by shoring up his homosexual credentials. In the second semester of his sophomore year, he had what he later described as his first, albeit unconsummated, gay love affair. “It was just the most amazing experience,” Lou explained. “I felt very bad about it because I had a girlfriend and I was always going out on the side, and subterfuge is not my hard-on.” He particularly remembered the pain of “trying to make yourself feel something towards women when you can’t. I couldn’t figure out what was wrong. I wanted to fix it up and make it okay. I figured if I sat around and thought about it, I could straighten it out.”

Lou and Shelley’s relationship rapidly escalated to a high level of game playing. Lou had more than one gay affair at Syracuse and would often try to shock her by casually mentioning that he was attracted to some guy. Shelley, however, could always turn the tables on him because she wasn’t threatened by Lou’s gay affairs and often turned them into competitions that she usually won for the subject’s attentions. If Shelley was a match for Lou, Lou was always ready to up the stakes. They soon got out of their depth playing these and other equally dangerous mind games, which led them into more complexities than they could handle.

Friends had conflicting memories of Lou’s gay life at Syracuse. Allen Hyman viewed him as being extraordinarily heterosexual right through college, whereas Sterling Morrison, who thought Lou was mostly a voyeur, commented, “He tried the gay scene at Syracuse, which was really repellent. He had a little fling with some really flabby, effete fairy. I said, ‘Oh, man, Lou, if you want to do it, I hate to say it but let’s find somebody attractive at least.’”

Homosexuality was generally presented as an unspeakable vice in the early 1960s. Nothing could have been considered more distasteful in 1962 America than the image of two men kissing. The average American would not allow a homosexual in his house for fear he might leave some kind of terrible disease on the toilet seat, or for that matter, the armchair. There were instances reported at universities in America during this time when healthy young men fainted, like Victorian ladies, at the physical approach of a homosexual. In fact, as Andy Warhol would soon prove, at the beginning of the 1960s the homosexual was considered the single most threatening, subversive character in the culture. According to Frank O’Hara’s biographer, Brad Gooch, “A campaign to control gay bars in New York had already begun in January 1964 when the Fawn in Greenwich Village was closed by the police. Reacting to this closing by police department undercover agents, known as ‘actors,’ the New York Times ran a front-page story headlined, ‘Growth of Overt Homosexuality in City Provokes Wide Concern.’” Besides the refuge large cities such as San Francisco and New York provided for homosexuals, many cultural institutions, especially the private universities, became home to a large segment of the homosexual community. Syracuse University, where there was a hotbed of homosexual activity, led by Lou’s favorite drama teacher, was no exception.

“As an actor, I couldn’t cut the mustard, as they say,” Reed recalled. “But I was good as a director.” For one project, Lou chose to direct The Car Cemetery (or the Automobile Graveyard) by Fernando Arrabal. Reed could scarcely have found a more appropriate form (the theater of the absurd) or subject (it was loosely based on the Christ mythology) as a reflection of his life. The story line followed an inspired musician to his ultimate betrayal to the secret police by his accompanist. Everything Lou wrote or did was about himself, and had the props been available, perhaps Reed would have considered a climactic electroshock torture scene. In giving the musician a messianic role against a backdrop of cruel sex and prostitution, the play appealed to the would-be writer-musician. “I’m sure Lou had a homosexual experience with his drama teacher,” attested another friend. “This drama teacher used to have guys go up to his room and put on girls’ underwear and take pictures of them and then he’d give you an A. One dean of men himself either committed suicide or left because he was associated with this group of faculty fags who were later indicted for doing all kinds of strange stuff with the students.”

The “first” gay flirtation cannot simply be overlooked and put aside as Morrison and Albin would want it to be. First of all, it had happened before. Back in Freeport during Lou’s childhood, he had indulged in circle jerks, and the gay experience left him with traits that he would develop to his advantage commercially in the near future. Foremost among them was an effeminate walk, with small, carefully taken steps that could identify him from a block away.

Despite an apparent desire originally to concentrate on a career as a writer, just as his guitar was never far from his hand, music was never far from Reed’s thoughts. Lou’s first band at Syracuse was a loosely formed folk group comprising Reed; John Gaines, a striking, tall black guy with a powerful baritone; Joe Annus, a remarkably handsome, big white guy with an equally good voice; and a great banjo player with a big Afro hairdo who looked like Art Garfunkel.

The group often played on a square of grass in the center of campus at the corner of Marshall Street and South Crouse. They also occasionally got jobs at a small bar called the Clam Shack. Lou didn’t like to sing in public because he felt uncomfortable with his voice, but he would sing his own folk songs privately to Shelley. He also played some traditional Scottish ballads based on poems by Robert Burns or Sir Walter Scott. Shelley, who would inspire Lou to write a number of great songs, was deeply moved by the beauty of his music. For her, his chord progressions were just as hypnotic and seductive as his voice. She was often moved to tears by their sensitivity.

Though he was devoting himself to poetry and folk songs, Lou had not dropped his initial ambition to be a rock-and-roll star. In addition to how to direct a play, Lou also learned how to dramatize himself at every opportunity. The showmanship would come in handy when Lou hit the stage with his rock music. Reed’s development of folk music was put in the shade in his sophomore year when he finally formed his first bona fide rock-and-roll band, LA and the Eldorados. LA stood for Lewis and Allen, since Reed and Hyman were the founding members. Lou played rhythm and took the vocals, Allen was on drums, another Sammie, Richard Mishkin, was on piano and bass, and Mishkin brought in Bobby Newman on saxophone. A friend of Lou’s, Stephen Windheim, rounded out the band on lead guitar. They all got along well except for Newman, a loud, obnoxious character from the Bronx who, according to Mishkin, “didn’t give a shit about anyone.” Lou hated Bobby and was greatly relieved when he left school that semester and was replaced by another sax player, Bernie Kroll, whom Lou fondly referred to as “Kroll the troll.”

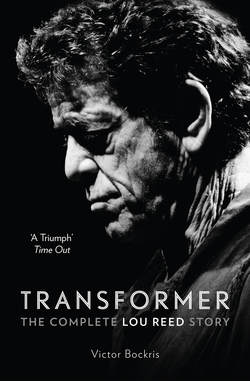

Reed playing in his Syracuse college band, LA and the Eldorados, with (left) Richard Mishkin. (Victor Bockris)

There was money to be made in the burgeoning Syracuse music scene, and the Eldorados were soon being handled by two students, Donald Schupak, who managed them, and Joe Divoli, who got them local bookings. “I had met Lou when we were freshmen,” Schupak explained. “Maybe because we were friends as freshmen, nothing developed into a problem because he could say, ‘Hey, Schupak, that’s a fucking stupid idea.’ And I’d say, ‘You’re right.’” Soon, under Schupak’s guidance and Reed’s leadership, LA and the Eldorados were working most weekends, playing frat parties, dances, bars, and clubs, making $125 a night, two or three nights a week.

Lou was strongly drawn to the musician’s lifestyle and haunts. Just off campus was the black section of Syracuse, the Fifteenth Ward. There he frequented a dive called the 800 Club, where black musicians and singers performed and jammed together. Lou and his band were accepted there and would occasionally work with some of the singers from a group called the Three Screaming Niggers. “The Three Screaming Niggers were a group of black guys that floated around the upstate campuses,” said Mishkin. “And we would pretend we were them when we got these three black guys to sing. So we would go down there once in a while and play. The people down there always had the attitude, the white man can’t play the blues, and we’d be down playing the blues. Then they’d be nice to us.” The Eldorados also sometimes played with a number of black female backing vocalists.

However, at first what made LA and the Eldorados stick out more than anything else was their car. Mishkin had a 1959 Chrysler New Yorker with gigantic fins, red guitars with flames shooting out of them painted on the side of the car, and “LA and the Eldorados” on the trunk. Simultaneously they all bought vests with gold lamé piping, jeans, boots, and matching shirts. Togged out in lounge-lizard punk and with Mishkin’s gilded chariot to transport them to their shows, the band was a sight when it hit the road. They had the kind of adventures that bond musicians.

Mishkin remembered, “One time we played Colgate and we were driving back in Allen’s Cadillac in the middle of a snowstorm, which eventually stopped us dead. So we’re sitting in the car smoking pot around 1 a.m., and we realized that we can’t do that all night because we’d die. The snow was deep, so we got out of the car and schlepped to this tiny town maybe half a mile away. We needed a place to stay so we went to the local hotel, which was, of course, full. But they had a bar there. Schupak was in the bar telling these stories about how he was in the army in the war, and Lewis and I are hysterical, we are dying it was so funny. Then the bartender said, ‘You can’t stay here, I have to close the bar.’ We ended up going to the courthouse and sleeping in jail.”

The Eldorados further distinguished themselves by mixing some of Lou’s original material into their set of standard Chuck Berry covers. One of Lou’s songs they played a lot was a love song he wrote for Shelley, an early draft of “Coney Island Baby.” “We did a thing called ‘Fuck Around Blues,’” Mishkin recalled. “It was an insult song. It sometimes went over well and it sometimes got us thrown out of fraternity parties.”

LA and the Eldorados played a big part in Lou’s life, providing him with many basic rock experiences, but he kept the band separate from the rest of his life at Syracuse. At first Lou wanted to make a point of being a writer more than a rock-and-roller. In those days, before the Beatles arrived, the term rock-and-roller was something of a put-down associated more with Paul Anka and Pat Boone than the Rolling Stones. Lou preferred to be associated with writers like Jack Kerouac. This dichotomy was spelled out in his limited wardrobe. Like the classic beatnik, Lou usually wore black jeans and T-shirts or turtlenecks, but he also kept a tweed jacket with elbow patches in his closet in case he wanted to come on like John Updike. However, in either role—as rocker or writer—Lou appeared somewhat uncomfortable. Therefore, in each role he used confrontation as a means both to achieve an effect and dramatize an inner turmoil that was quite real. For Hyman and others, this sometimes made working with Lou exceedingly difficult.

According to Allen, “One of the biggest problems we had was that if Lou woke up on the day of the job and he decided he didn’t want to be there, he wouldn’t come. We’d be all set up and looking for him. I remember one fraternity party, it was an afternoon job, we were all set up and ready to go and he just wasn’t there. I ran down to his room and walked through about four hundred pounds of his favorite pistachio nuts, and then I found him in bed under about six hundred pounds of pistachio nuts—in the middle of the afternoon. I looked at him and said, ‘What are you doing? We have a job!’ And he said, ‘Fuck you, get out of here. I don’t want to work today.’ I said, ‘You can’t do this, we’re getting paid!’ Mishkin and I physically dragged him up to the show. Ultimately he did play, but he was very pissed off.”

Reed seemed to at once want the spotlight and to hate it.

“Lou’s uniqueness and stubbornness made him really different than anyone I had ever known,” added Mishkin. “He was a terrible guy to work with. He was impossible. He was always late, he would always find fault with everything that the people who had hired us expected of us. And we were always dragging him here and dragging him there. Sometimes we were called Pasha and the Prophets because Lou was such a son of a bitch at so many gigs he’d upset everyone so much we couldn’t get a gig in those places again. He was as ornery as you can get. People wouldn’t let us back because he was so absolutely rude to people and just so mean and unappreciative of the fact that these people were paying us to get up and play music for them. He couldn’t have cared less. So we used the name Pasha and the Prophets in order to play there again. And then the people who hired us were so drunk they wouldn’t remember. He would never dress or act in a way so that people would accept him. He would often act in a confrontational manner. He wanted to be different.

“But Lou was ambitious. He wanted to be—and said this to me in no uncertain terms—a rock-and-roll star and a writer.”

***

In May 1962, sick of the stodgy university literary publication and keen to make their mark, Lewis and Lincoln, along with Stoecker, Gaines, Tucker, et al., put out two issues of a literary magazine called the Lonely Woman Quarterly. The title was based on Lou’s favorite Ornette Coleman composition, “Lonely Woman.”

Originating out of the Savoy with the encouragement of Gus Joseph, the first issue contained an untitled story, mentioned in the previous chapter, signed Luis Reed. It described Sidney Reed as a wife-beater, and Toby as a child molester. Shelley, who was involved in the publication, was convinced that just as Lou’s homosexual affair was mostly an attempt to associate with the offbeat gay world, the story was a conspicuous attempt to build his image as an evil, mysterious person. He was smart enough, she thought, to see that this was going to make readers uncomfortable. “And that’s what Lou always wanted to do,” she said, “make people uncomfortable.”

The premier issue of LWQ brought “Luis” his first press mention. In reviewing the magazine, the university’s newspaper, the Daily Orange, had interviewed Lincoln, who boasted that the magazine’s one hundred copies had sold out in three days. Indeed, the first issue was well received, but when everyone else on its staff apparently got lazy, Lou put out issue number two, which featured his second explosive piece, printed on page one. Called “Profile: Michael Kogan—Syracuse’s Miss Blanding,” it was the most attention-grabbing project Lou ever pulled off at Syracuse: a deftly executed, harsh attack upon the student who was head of the Young Democrats Party at the University. Allen Hyman recalled, “It said something like he [Kogan] should parade around campus with an American flag up his ass, which at the time was a fairly outrageous statement.” Unfortunately, Kogan’s father turned out to be a powerful corporation lawyer. “He decided that the piece was libelous,” remembered Sterling, “and he’d bust Lou’s ass. So they hauled him before the dean. But … the dean started shifting to Lou’s side. Afterwards, the dean told Lou to finish up his work and get his ass out of there, and nothing would happen to him.” By May of 1962, Reed’s literary career was off to a running start.

Despite this, Lou’s relationship with Shelley—not his classes—had dominated his sophomore year. They had spent as many of their waking hours together as was possible, camping out over the weekends in friends’ apartments, using fraternity rooms, cars, and sometimes even bushes to make love. Lou received a D in Introduction to Math and an F in English History. Then he got in trouble with the authorities again when a friend was busted for smoking pot and ratted on a number of people, including Lewis and Ritchie Mishkin.

“We smoked all the time,” admitted Mishkin. “But we didn’t smoke and work. We may have played and then smoked after and then jammed. Anyway, the dean of men called Lou, me, and some other people into his office and said, ‘We know you were smoking pot, so give us the whole story.’ We were terrified, at least I was. But nothing happened. Lou was angry. With the authorities and with the informer. But they were pretty soft on us. We were lucky, but then all they had to go on was the ‘he said, she said’ kind of evidence, so there was a limit to what they could do. But they had us in the office and they did the old, ‘We know because so-and-so said …’”

As a result of these numerous transgressions, and with his apparent academic torpor at the end of his sophomore year, Reed was put on academic probation.

***

The summer of 1962 was somewhat difficult for Lou. This was the first time he had been separated from Shelley for more than a day, and he took it hard. First, in an attempt to exert his control over her across the thousand miles that separated them, he embarked on a zealous letter-writing campaign, sending her long, storylike letters every day. They would begin with an account of his daily routine—he would go to the local gay bar, the Hayloft, every night—and tweak Shelley with suggestive comments. Then, in the middle of a paragraph the epistle would abruptly shift from reality to fiction and Lou would take off on one of his short stories, usually mirroring his passion and longing for Shelley. An exemplary story sent across the country that summer was “The Gift,” which appeared on the Velvet Underground’s second album, White Light/White Heat, and perfectly summed up Lou’s image of himself as a lonely Long Island nerd pining for his promiscuous girlfriend. “The Gift” climaxed with the lovelorn author desperately mailing himself to his lover in a womblike cardboard box. The final image, in the classic style of Yiddish humor that informed so much of Reed’s work, had the boyfriend being accidentally killed by his girlfriend as she opened the box with a large sheet-metal cutter.

Shelley, a classic passive-aggressive character, rarely responded in kind, but she did talk to Lou on the phone several times that summer, and he did not like what he heard at all. Lou had expected Shelley to remain locked in her room thinking of nothing but him. But Shelley wasn’t that kind of girl. Despite having commenced the vacation with a visit to the hospital to have her tonsils out, by July she was platonically dating more than one guy and at least one was madly in love with her. Despite the fact that Shelley was really loyal to Lou, the emotions Lou addressed in “The Gift” were his. He paced up and down his room in frustration. He couldn’t stand not having Shelley under this thumb. It was driving him insane.

Then he hit on a plan. Why not go out and visit her? After all, he was her boyfriend, he was writing to her every day or so and had called her several times. It sounded like the right thing to do. His parents, who had kept a wary eye on their wayward son that summer, still frowning on his naughty visits to the Hayloft and daily excursions on the guitar, were only too happy to support a venture that they felt was taking him in the right direction. At the beginning of August he flew out to Chicago.

Shelley had been adamantly against the planned visit, warning Lou on the phone that her parents wouldn’t like him, that it was a big mistake and wouldn’t work out at all. But Lou, who wanted, she recalled, “to be in front of my face,” insisted.

By now Lou had developed a pattern of reaction to any new environment he entered. His plan was to split up any group, polarizing them around him. In a family situation, as soon as he walked into anybody’s house, he took the position that the father was a tyrannical ogre whom the mother had to be saved from. On his first night in the Albins’ home, he cleverly drew Mr. Albin into a political discussion and then, marking him for the bullheaded liberal Democrat that he was, expertly lanced him with a detailed defense of the notorious conservative columnist William Buckley. While Shelley sat back and watched, half-horrified, half-mesmerized, Mr. Albin became increasingly apoplectic. Lou was obviously not the right man for his daughter. In fact, he didn’t even want him in the house.

The Albins had rented a room for Lou in nearby Evanston, at Northwestern University. Using every trick in his book, Lou pulled a double whammy on Mr. Albin, driving his car into a ditch later the same night when bringing Shelley back from the movies at 1 a.m., forcing her father to get up, get dressed, come out, and help haul out the mauled automobile.

Things went downhill from there. Lou made a valiant attempt to win over Mrs. Albin. Having dinner with her and Shelley one night when the man of the house was absent, Lou launched into his classic rap, saying, “Gee, you’re clearly very nice. If it wasn’t for the ogre living in the house …” But Mrs. Albin was having none of his boyish charm. She had surreptitiously read Lou’s letters to Shelley that summer and formed a very definite opinion about Lou Reed: she hated him with a passion—and still does more than thirty years later. In her opinion, Lou was ruining her daughter’s life.

As an upshot of Lou’s visit, Shelley’s parents informed her that if she continued to see Lou in any way at all, she would never be allowed to return to Syracuse. Naturally, swearing that she would never set eyes upon the rebel again, Shelley now embarked upon a secret relationship with Lou that trapped her exactly where Reed wanted. Since Shelley had no one outside of Lou’s circle in whom she could confide about her relationship with him, she was essentially under his control. From here on Lou would always attempt to program his women. His first move would always be to amputate them from their former lives so that they accepted that the rules were Lou’s.