Читать книгу Transformer: The Complete Lou Reed Story - Victor Bockris - Страница 18

The Formation of the Velvet Underground

ОглавлениеON THE LOWER EAST SIDE: 1965

The best things come, as a general thing, from the talents that are members of a group; every man works better when he has companions working in the same line, and yielding to stimulus and suggestion, comparison, emulation.

Henry James

It was through Pickwick that Lou met the man who would be the single most important long-lasting collaborator in his life, John Cale. One day in January 1965, Lou, who had not let hepatitis slow him down, had ingested a copious quantity of drugs. As he felt the rush of creativity coming on, he leafed through Eugenia Sheperd’s column in a local tabloid and came across an item about ostrich feathers being the latest fashion craze. Flinging down the paper and grabbing his guitar with the manic pent-up humor that fueled so much of his work, Lou spontaneously created a new would-be dance craze in a song called “The Ostrich.” It joyously told the dancer to put his head on the floor and let his partner step on it. What better self-image could Lou have possibly come up with than this nutty notion, except that the dancers give each other electroshocks?

Although it appeared unlikely that even rock-crazed teenagers, currently dancing the twist and the frug, would go for this masochistic idea, Shupak’s partner, Terry Phillips, desperate for a hit to exonerate his claim that the wave of the future was in rock, immediately snapped that this could be the hit single they had been looking for. With his spacey head full of images of millions of kids across America stomping on each other’s head (he was ten years ahead of his time), the ersatz Andrew Oldham (the Rolling Stones’ equally young and inexperienced producer) got the rock executives out in the warehouse to agree to his proposal that they release “The Ostrich” as a single by a make-believe band called the Primitives. When the record came out, they received a call from a TV dance show, much to their surprise, requesting a performance of “The Ostrich” by “the band.” Eager to promote his project, Phillips persuaded the Pickwick people to let him put together a real band to fill the bill. He saw the pleasingly pubescent-looking Lewis as a natural for lead singer. But he was less than enthusiastic about the other musicians, who did not have the requisite look to con the teen market into spending their spare dollars on “The Ostrich.” Frantic to get the show on the road, Phillips began to search for a backup band for Lou Reed.

From the Pickwick studio the story cuts to Terry Phillips at an Upper East Side Manhattan apartment jammed with a bunch of pasty-faced party people all yukking it up and trying to be cool despite having no idea at all about anything. Ensconced among them, highly amused and somewhat above it all, were the unlikely duo of a big-boned Welshman with a sonorous voice named John Cale and his partner and flatmate, the classic nervy-looking underground man Tony Conrad. In their early twenties and sporting hair unfashionably long for those days, Cale was a classical-music scholar, Conrad an underground filmmaker, and they were both members of one of the midsixties most avant-garde music groups in the world, La Monte Young’s Theater of Eternal Music. On the trail of female companions and good times, they had been brought to the party by the brother of the playwright Jack Gelber, who had recently written a famous play about heroin called The Connection. Spotting these reasonably attractive and slightly eccentric-looking guys with long hair, Terry Phillips immediately asked them if they were musicians. Receiving an affirmative response, he took it for granted that they played guitars (in fact Cale played an electrically amplified viola as well as several Indian instruments) and snapped, “Where’s the drummer?”

The two underground artists, who took their work highly seriously, went along with Phillips as a kind of joke, claiming they did have a drummer so as not to jeopardize the opportunity to make some pocket money. The next day, along with their good friend Walter De Maria, who would soon emerge as one of the leading avant-garde sculptors in the world and was doing a little drumming on the side, they showed up at Pickwick studios as instructed.

Cale, Conrad, and De Maria were highly amused by the bogus setup at Pickwick. To them, the Pickwick executives in polyester suits, who suspiciously pressed contracts into their hands, were hilarious caricatures of rock moguls. On close inspection, as Conrad recalled, the contracts stipulated that they would sign away the rights to everything they did for the rest of their lives in exchange for nothing. After brushing aside this attempt to extract an allegiance more closely resembling indentured servitude than business management, Conrad, Cale, and De Maria were introduced to Lou Reed. He assured them that it would take no time at all to learn their parts to “The Ostrich” since all the guitar strings were tuned to a single note. This information left John Cale and Tony Conrad openmouthed in astonishment since that was exactly what they had been doing at La Monte Young’s rigorous eight-hours-a-day rehearsals. They realized Lou had some kind of innate musical genius that even the salesmen at the studio had picked up on. Tony got the impression that “Lou had a close relationship with these people at Pickwick because they recognized that he was a very gifted person. He impressed everybody as having some particularly assertive personal quality.”

Cale, Conrad, and De Maria agreed to join “The Primitives” and play shows to promote the record on the East Coast. It was primarily a camp lark, but it would also give them a glimpse into the world of commercial rock and roll, in which they were not entirely uninterested.

And so it came about that in their first appearance together, Lou Reed and John Cale found themselves, without prior rehearsal, running onto the stage of some high school in Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley following a bellowed introduction: “And here they are from New York—The Primitives!” Confronting a barrage of screaming kids, the band launched into “The Ostrich.” At the end of the song the deejay screamed, rather portentously, “These guys have really got something. I hope it’s not catching!”

Far from being catching, “The Ostrich” died a quick death. After racing around the countryside in a station wagon for several weekends getting a taste of the reality of the rock life without roadies, the band packed it in. Terry Phillips and the Pickwick executives ruefully left off their dream of seeing “The Ostrich” sail into the hemisphere of the charts and returned to the dependable work of Jack Borgheimer.

The attempted breakout had its repercussions though, primarily in introducing Lou to John, who held the keys to a whole other musical universe. The fact was that Lou, like many creative people, had a low threshold for boredom and realized that Terry Phillips’s vision was too narrow to allow him to grow.

***

When Lou started to visit John Cale in his bohemian slum dwelling at 56 Ludlow Street in the deepest bowels of Manhattan’s Lower East Side, Reed knew nothing of La Monte Young, or his Theater of Eternal Music, and had little sense of the world he was entering. In keeping with the egocentric personalities he had been cultivating since his successes on the Syracuse University poetry, music, and bohemian scenes, Lou was out for his own ends and at first showed little interest in whatever it was that John was into. Instead, the rock-and-roller set about seducing the classicist.

Cale, for his part, was taken by Reed’s rock-and-roll persona and what little he had witnessed of his spontaneous composition of lyrics, but took a somewhat snooty view of Reed’s initial attempts to strike up a collaborative friendship. “He was trying to get a band together,” Cale said. “I didn’t want to hear his songs. They seemed sorry for themselves. He’d written ‘Heroin’ already, and ‘I’m Waiting for My Man,’ but they wouldn’t let him record it, they didn’t want to do anything with it. I wasn’t really interested—most of the music being written then was folk, and he played his songs with an acoustic guitar—so I didn’t really pay attention because I couldn’t give a shit about folk music. I hated Joan Baez and Dylan. Every song was a fucking question!”

Despite having been a musical prodigy and, before the age of twenty-five, studied with some of the greatest avant-garde composers of the century, by 1965 Cale felt his career was going nowhere. “I was going off into never-never land with classical notions of music,” he said, desperate for a new angle from which to approach music. The sentiment was shared by his family, putting additional pressure on him to get a job. Just like Lou’s mother, Mrs. Cale, a schoolteacher in a small Welsh mining village married to a miner, complained that John would never make a living as a musician and should become a doctor or a lawyer.

Like a bullterrier nipping at pants legs, Lou kept after John, feeling intuitively that the Welshman might provide a necessary catalyst for his music. Eventually, Lou got his way and Cale began to take Lou’s lyrics seriously. “He kept pushing them on me,” Cale recalled, “and finally I saw they weren’t the kind of words you’d get Joan Baez singing. They were very different, he was writing about things other people weren’t. These lyrics were very literate, very well expressed, they were tough.”

Once John grasped what Lou was doing—Method acting in song, as he saw it—he glimpsed the possibility of collaborating to create something vibrant and new. He figured that by combining Young’s theories and techniques with Lou’s lyrical abilities, he could blow himself out of the hole his rigid studies had dug him into. Lou also introduced John to a hallmark of rock-and-roll music—fun—and his youthful enthusiasm was infectious. “We got together and started playing my songs for fun,” Reed recalled. “It was like we were made for each other. He was from the other world of music and he fitted me perfectly. He would fit things he played right into my world, it was so natural.”

“What I saw in Lou’s musical concept was something akin to my own,” agreed Cale. “There was something more than just a rock side to him too. I recognized a tremendous literary quality about his songs which fascinated me—he had a very careful ear, he was very cautious with his words. I had no real knowledge of rock music at that time, so I focused on the literary aspect more.” Cale was so turned on by the connection he started weaning Reed away from Pickwick.

Cale immediately got to work with Reed on orchestrations for the songs. The two men labored over the pieces, each feeding off the fresh ideas of his counterpart. “Lou’s an excellent guitar player,” Cale said. “He’s nuts. It has more to do with the spirit of what he’s doing than playing. And he had this great facility with words, he could improvise songs, which was great. Lyrics and melodies. Take a chord change and just do it.” Cale was an equally exciting player. Unaware of any rock-and-roll models to emulate, he answered Reed’s sonic attacks with illogical, inverted bass lines or his searing electric viola, which sounded, he said, “like a jet engine!”

Meanwhile, as he got to know Lou, and Reed began to unwrap the elements of his legend, John discovered that they had something else in common, “namely,” Lou would deadpan, “dope.” Reed joked dismissively about their heroin use, commenting that when he and Cale first met, they started playing together “because it was safer than dealing dope,” which Reed was apparently still dabbling in. Whilst fully admitting his involvement with heroin, Lou always insisted, and friends tended to concur, that “I was never a heroin addict. I had a toe in that situation. Enough to see the tunnel, the vortex. That’s how I handled my problems. That’s how I grew up, how I did it, like a couple hundred thousand others. You had to be a gutter rat, seeking it out.”

While rationalizing his drug use, Reed also made it clear that it provided him with a shield necessary for both his life and work: “I take drugs just because in the twentieth century in a technological age, living in the city, there are certain drugs you can take just to keep yourself normal like a caveman. Not just to bring yourself up and down, but to attain equilibrium you need to take certain drugs. They don’t get you high, even, they just get you normal.”

Despite the fact that drug taking was widely accepted, practiced, and even celebrated among the artistic residents of Cale’s Lower East Side community, because it was addictive, dangerous, and could be extremely destructive, heroin had a stigma attached to it that led users to keep it private. Thus Cale and Reed found themselves bonded not only by a musical vision and youthful anarchy, but by the secret society heroin users tend to form. The cozy, intimate feelings the drug can bring on magnified their friendship.

Lou started spending a lot of his spare time at John’s. Before long he was staying there for weeks at a time without bothering to return to his parents’ house in Freeport. Lou had long since become fed up with his parents, avoiding them at all costs, and stopping by their house only when in need of money, food, clean laundry, or to check up on the well-being of his dog. Even his involvement with Pickwick was fading under the spell of the Lower East Side rock-and-roll lifestyle. “Lou was like a rock-and-roll animal and authentically turned everybody on,” recalled Tony Conrad. “He really had a deep fixation on that, and his lifestyle was completely compatible and acclimatized to it.”

Cale’s was a match for Reed’s mercurial personality. Moody and paranoid, he too was easily bored and looking for action. John responded to Lou’s driving energy with equal passion, not only sharing Reed’s musical explosions but also providing a creative atmosphere and spiritual home for him. Conrad saw that Lou “was definitely a liberating force for John, but John was an incredible person too. He was very idealistic, putting himself behind what he was interested in and believed in in a tremendous way. John was moving at a very, very fast pace away from a classical training background through the avant-garde and into performance art then rock.” The relationship between John and Lou grew quickly, and it wasn’t long before they started thinking about Lou’s getting out of Freeport, where he was still living very uncomfortably under the disapproving gaze of his parents. Lou was eager to get something happening. “I took off, so there was more room in the pad, and John invited him to come over and stay where I had been staying,” said Conrad. “Lou moved in, which was great because we got him out of his mother’s place.”

“We had little to say to each other,” Lou said of the deteriorating relationship with his parents. “I had gone and done the most horrifying thing possible in those days—I joined a rock band. And of course I represented something very alien to them.”

The hard edge of the Lower East Side kicked Lou into gear. The neighborhood was the loam, as Allen Ginsberg had said, out of which grew “the apocalyptic sensibility, the interest in mystic art, the marginal leavings, the garbage of society.” As Lou discovered John’s ascetic yet sprawling Lower East Side landscape with its population of what Jack Kerouac described as like-minded bodhisattvas, he found himself walking in the footsteps of Stephen Crane (who had come there straight from Syracuse University at the end of the previous century to write Maggie: A Girl of the Streets and wrote to a friend “the sense of a city is war”), John Dos Passos, e. e. cummings, and, most recently, the beats. Indeed, Reed could have walked straight out of the pages of Ginsberg’s Howl for he too would, like one of the poem’s heroes, “purgatory his torso night after night with dreams, with drugs, with waking nightmares, alcohol and cock and endless balls.” Most importantly, the Ludlow Street inhabitants shared with Lou a communal feeling that society was a prison of the nervous system, and they preferred their individual experience. The gifted among them had enough respect for their personal explorations to put them in their art, just as John and Lou were doing, and make them new. Friends from college who visited him there couldn’t believe Lou was living in these conditions, but among the drug addicts and apocalyptic artists of every kind, Lou found, for the first time in his life, a real mental home.

The funky Ludlow Street had for a long time been host to creative spirits like the underground filmmakers Jack Smith and Piero Heliczer. When Lou moved in, an erratic but inventive Scotsman named Angus MacLise, who often drummed in La Monte’s group, lived in the apartment next door. Cale’s L-shaped flat opened into a kitchen, which housed a rarely used bathtub. Beyond it was a small living room and two bedrooms. The whole place was sparsely furnished, with mattresses on the floor and orange crates that served as furniture and firewood. Bare lightbulbs lit the dark rooms, paint and plaster chipped from the woodwork and the walls. There was no heat or hot water, and the landlord collected the $30 rent with a gun. When it got cold during February to March of 1965, they ran out into the streets, grabbed some wooden crates, and threw them into the fireplace, or often sat hunched over their instruments with carpets wrapped around their shoulders. When the toilet stopped up, they picked up the shit and threw it out the window. For sustenance they cooked big pots of porridge or made humongous vegetable pancakes, eating the same glop day in and day out as if it were fuel.

As he began to work with Cale to transform his stark lyrics into dynamic symphonies, he drew John into his world. John found Lou an intriguing, if at times dangerous, roommate. What they had in common was a fascination with the language of music and the permanent expression of risk. “In Lou, I found somebody who not only had artistic sense and could produce it at the drop of a hat, but also had a real street sense,” John Cale recalled. “I was anxious to learn from him, I’d lived a sheltered life. So, from him, I got a short, sharp education. Lou was exorcising a lot of devils back then, and maybe I was using him to exorcise some of mine.”

Lou maintained a correspondence with Delmore Schwartz that led his mentor to believe that he was still definitely on the path to distilling his essence in words. Lou wrote in one letter in early 1965, just after moving to New York City, “If you’re weak NY has many outlets. I can’t resist peering, probing, sometimes participating, other times going right to the edge before sidestepping. Finding viciousness in yourself and that fantastic killer urge and worse yet having the opportunity presented before you is certainly interesting.”

With John in tow, Lou would befriend a drunk in a bar and then, after drawing him out with friendly conversation, according to Cale, suddenly pop the astonishing question, “Would you like to fuck your mother?” John recalled this side of Lou during his early days at Ludlow Street, commenting, “From the start I thought Lou was amazing, someone I could learn a lot from. He had this astonishing talent as a writer. He was someone who’d been around and was definitely bruised. He was also a lot of fun then, though he had a dangerous streak. He enjoyed walking the plank and he could take situations to extremes you couldn’t even imagine until you’d been there with him. I thought I was fairly reckless until I met Lou. But I’d stop at goading a drunk into getting worse. And that’s where Lou would start.” This kind of behavior got them into some hairy situations, abhorred by Cale—who was not as verbally adroit as Lou and was at times agoraphobic and lived in fear of random violence. “I’m very insecure,” said Cale. “I use cracks on the sidewalk to walk down the street. I’d always walk on the lines. I never take anything but a calculated risk, and I do it because it gives me a sense of identity. Fear is a man’s best friend.”

Money was a constant problem. Although Lou had use of his mother’s car and could return to Freeport whenever he desired, and kept working at Pickwick until September, he had nothing beyond his $25.00 per week. He picked up whatever money he could in doing gigs with John, some of them impromptu. Once, they went up to Harlem to play an audition at a blues club. When the odd-looking couple were turned down by the club management, they went out to play on the sidewalk and raked in a sizable amount of money. “We made more money on the sidewalks than anywhere else,” John recalled.

“We were living together in a thirty-dollar-a-month apartment and we really didn’t have any money,” Lou testified. “We used to eat oatmeal all day and all night and give blood among other things, or pose for these nickel or fifteen-cent tabloids they have every week. And when I posed for them my picture came out and it said I was a sex-maniac killer and that I had killed fourteen children and had tape-recorded it and played it in a barn in Kansas at midnight. And when John’s picture came out in the paper, it said he had killed his lover because his lover was going to marry his sister, and he didn’t want his sister to marry a fag.”

Lou was creating the myth of his own Jewish psychodrama. It had become a custom of Lou’s to sicken people with stories of his shock treatment, drug use, and problems with the law. This was the sort of image-building Reed would, in a search for a personality and voice to call his own, perfect in the coming years, culminating in a series of infamous personas in the 1970s. “At that time Lou was relating to me the horrors of electric-shock therapy, he was on medication,” Cale recounted. “I was really horrified. All his best work came from living with his parents. He told me his mother was some sort of ex-beauty queen and his father was a wealthy accountant. They’d put him in a hospital where he’d received shock treatments as a kid. Apparently he was at Syracuse and was given this compulsory choice to do either gym or ROTC. He claimed he couldn’t do gym because he’d break his neck, and when he did ROTC, he threatened to kill his instructor. Then he put his fist through a window or something, and so he was put in a mental hospital. I don’t know the full story. Every time Lou told me about it he’d change it slightly.”

Lou and John resolved to form a band, orchestrate their material into a performable and recordable body of work, and venture out into the world to unleash their music. “When we first started working together, it was on the basis that we were both interested in the same things,” said Cale. “We both needed a vehicle; Lou needed one to carry out his lyrical ideas and I needed one to carry out my musical ideas. It seemed to be a good idea to put a band together and go up onstage and do it, because everybody else seemed to be playing the same thing over and over. Anybody who had a rock-and-roll band in those days would just do a fixed set. I figured that was one way of getting on everybody’s nerves—to have improvisation going on for any length of time.”

***

While Lou was wrapping himself in the troubled dreams and screams of his music, elevating himself, as one friend saw it, to another level of anger and coolness, and becoming progressively weirder, he began to put some distance between himself and his past. True, he still borrowed his mother’s car to go into dangerous parts of town to score drugs, and made the occasional trip or phone call home, but he began to amputate those friends with whom he had maintained contact post-Syracuse. The first to go was the stalwart Hyman. Living in Manhattan with his wife and going to law school, his former buddy had lost the ability to provide anything for Lou (save a free meal). Mishkin still fulfilled a function in that he had a big space in Brooklyn where Lou sometimes rehearsed, and a yacht called the Black Angel tethered at the 79th Street Boat Basin where they sometimes socialized, but Mishkin was maintaining contact with Lou at a price. “At that point he was putting me down more than he would have at Syracuse,” Ritchie recalled. “He was on the way to what he became.”

Parting ways is common among former schoolmates who move on to new jobs and allegiances. The amputations that struck more deeply and perhaps more definitively were made by Lou of the people who had been most influential, the ones who knew too much about him.

After a period of psychiatric rehabilitation, Lincoln Swados had re-emerged on the New York scene, living in the East Village not far from Lou. For a short time he was making a reputation for himself as a comic-strip illustrator and stand-up comedian. But soon he beat Lou hands down in the lunatic sweepstakes by stepping in front of an oncoming subway train, saying, “I am a very bad person, I am a very bad person …” Moving aside at the last minute, he survived—minus an arm and a leg. Subsequently, he became something of a fixture on the Lower East Side as a crippled street performer. Lincoln’s sister, Elizabeth, who had gone on to a distinguished career as a playwright, was apparently quite upset by the extent to which Lou, rather than opening up to Lincoln after this tragic episode, put even more distance between them. Lincoln, though, apparently had a perceptive understanding of his friend’s motives. “Lou pretends to be like us,” he told his ex-girlfriend, the journalist Gretchen Berg, “but he’s really not, he’s really someone else. He’s really a businessman who has very definite goals and knows exactly what he wants.”

Interestingly, Delmore Schwartz, who was now in the final year of his life, had drawn a similar conclusion. A Syracuse classmate of Lou’s who ran into Schwartz in Manhattan one day was astonished to discover that “he looked really bad. He had on a black raincoat which looked like it was covered with toothpaste stains. He seemed to have been drinking, maybe he was drunk. And the only thing he was interested in discussing was his dislike for everyone at Syracuse; how Lou Reed and Peter Locke were spies paid by the Rockefellers.” When Lou discovered that Schwartz was living in the dilapidated fleabag Dixie Hotel on West 48th Street, he went there to make contact, but Delmore let him have it with both barrels, screaming, “If you ever come here again, I’ll kill you!” scaring off a shaken Reed, who recalled, “He thought I’d been sent by the CIA to spy on him, and I was scared because he was big and he really would have killed me.”

The third mind in his life at Syracuse, Shelley Albin, reversed the amputation, cutting Lou out of her life when she married Ronald Corwin, who had been a big wheel on the Syracuse campus from 1963 to 1965 as the head of the local chapter of CORE, and whom Lou subsequently characterized as an “asshole airhead.” The marriage was a blow to Lou in as much as he still considered Shelley to be “his” girlfriend, even though he had neither seen nor apparently made any attempt to contact her since the summer of 1964. Still, he had not carried on a romantic relationship with anyone else. Shelley would remain a thorn in his side at least throughout the end of the 1970s, inspiring some of his most poignant, if vicious, love songs.

The only people Lou seemed incapable of amputating were his parents, who were vividly remembered by friends as a pair of never seen but constantly present just off stage ogrelike specters threatening at any moment to have Lou committed (despite the fact that he was now twenty-three years old and legally beyond their reach).

***

A month into his collaboration with Cale, one of those chance meetings that have often formed rock groups took place when Lou bumped into his friend from Syracuse, Sterling Morrison, walking in the West Village. Lou invited Sterling to Ludlow Street to play some music. By then Angus MacLise was playing drums around Lou and John. The next time Tony Conrad dropped by, he discovered that the Reed–Cale relationship had blossomed with MacLise and Morrison into what they were beginning to call a group. They had even made a first stab at a name, trying on for several months the Warlocks (which, incidentally, was the name being used at the same time on the West Coast by the proto-Grateful Dead), and were taping rehearsals. The music, heavily influenced by La Monte Young via MacLise and Cale, but equally by the doo-wop and white rock favored by Reed and Morrison, was ethereal and passionate.

Lou and Angus collaborated on an essay called “Concerning the Rumor That Red China Has Cornered the Methedrine Market and Is Busy Adding Paranoia Drops to Upset the Mental Balance of the United States,” a nutty, stoned credo of the band’s basic precepts. It read, in part, “Western music is based on death, violence and the pursuit of PROGRESS … The root of universal music is sex. Western music is as violent as Western sex … Our band is the Western equivalent to the cosmic dance of Shiva. Playing as Babylon goes up in flames.”

Their original precepts were to dedicate themselves with an almost religious fervor to their collective calling, to sacrifice being immediately successful, to be different, to hold on to a personality of their own, never to try to please anyone but themselves, and never to play the same song the same way. The group discovered and exploited musical traditions lost to their contemporaries, rejecting outright the popular conventions of the day. “We actually had a rule in the band,” Reed explained. “If anybody played a blues lick, they would be fined. Everyone was going crazy over old blues people, but they forgot about all those groups, like the Spaniels, people like that. Records like ‘Smoke from Your Cigarette,’ and ‘I Need a Sunday Kind of Love,’ the ‘Wind’ by the Chesters, ‘Later for You, Baby’ by the Solitaires. All those really ferocious records that no one seemed to listen to anymore were underneath everything we were playing. No one really knew that.”

“Our music evolved collectively,” Sterling reported. “Lou would walk in with some sort of scratchy verse and we would all develop the music. It almost always worked like that. We’d all thrash it out into something very strong. John was trying to be a serious young composer; he had no background in rock music, which was terrific, he knew no clichés. You listen to his bass lines, he didn’t know any of the usual riffs, it was totally eccentric. ‘Waiting for the Man’ was very weird. John was always exciting to work with.”

Their first complete success in terms of arrangements was “Venus in Furs.” When Cale initially added viola, grinding it against Reed’s “ostrich” guitar, illogically and without trepidation, a tingle of anticipation shot up his spine. They had, he knew, found their sound, and it was strong. Cale, who applied the mania to the sound, recalled, “It wasn’t until then that I thought we had discovered a really original, nasty style.” With the words of this song, wrote the British critic Richard Williams, “Lou Reed was to change the agenda of pop music once and for all. But it wasn’t just the words either. ‘Heroin’ and ‘Venus in Furs’ were given music that fitted their themes, and that didn’t sound like anything anybody had played before. Out went the blues tonality and the Afro-American rhythms, the basic components of all previous rock and roll. The prevailing sound was the grinding screech of Cale’s electric viola and Reed’s guitar feedback, while the tempo speeded up and slowed down according to the momentary requirements of the lyric.”

The chemistry of their personalities was more fragile. On one occasion, Lou played a new song he had written and John immediately started adding an improvised viola part. Sterling muttered something about its being a good viola part. Lou looked up and snapped, “Yeah, I know. I wrote the song just for that viola part. Every single note of it I knew in advance.” Although unable to outdo Lou verbally, John stuck to his guns through music. Several observers of the scene believed that John did more than that—he actually brought Lou Reed out of himself, completed him as it were. Some believe that without John Cale, the Lou Reed who became a legend would not have been born.

“It’s a fascinating relationship,” commented one friend. “That John worked with Cage and La Monte Young would be interesting enough if his career ended there, but that he met Lou and saw something in Lou despite the fact that Lou did not have the same kind of training that he had. I think he recognized that and must have done much in his way to nurture it and allowed it also to change the course of his life.”

Sterling Morrison hid this nervousness under a cloud of silence when anything went wrong. His personality often made him a useful buffer between Reed and Cale, but it could also cause problems when, without informing anybody that he was upset, he would simply clam up. Insecure about his playing, and in need of constant encouragement, Sterling stood in the background and tentatively muttered the choruses he was supposed to sing. One friend recalled that “it was typical of Sterling to play a wonderful solo and pretend he didn’t care, but then after an hour sidle up and ask, ‘How was the solo?’”

The joker in the deck was Angus MacLise. Not only did the band get the majority of their electricity from his apartment, but Angus was, by all accounts, a lovely, whimsical, gnomelike man, inspired, inspirational, and a serious methedrine addict. As a drummer, he was intuitive and complex, pounding out an amazing variety of textures and licks culled from cultures around the world. He was influenced a lot by his travels, by the dervishes of the Middle East and people he had met in India and Nepal. A visionary poet and mystic who also belonged to La Monte Young’s coterie, MacLise believed in listening to the essence of sound and relating it to one’s inner being. “Angus had dreamy notions of art—I mean real dreamy,” commented Sterling. “So did we, otherwise we could have made a whole lot more money. We were never in it for the money, we felt very strongly about the material, and we wanted to be able to play it. We said screw the marketing.”

Both Cale and MacLise continued to play with the Theater of Eternal Music through 1965 in between rehearsing with the Warlocks, although this contravened Lou’s need for total allegiance and commitment. This made La Monte Young almost a third mind in the construction of the band’s basic precepts. It was characteristic of that period and place—specifically the East Village—that certain figures, such as La Monte Young, Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, Allen Ginsberg, were ensconced with an adoring, disciplelike entourage of followers and fellow workers. It is significant that despite his two bandmates’ close connections with one of the most charismatic figures of the period, Lou Reed never met La Monte Young during his entire career with the Velvet Underground. Reed understood that people who really wanted to make it on their own—to be stars—had to keep their distance from the vortex of such strong groups.

In fact, the central paradox of Lou’s career—particularly in the 1960s—was that by entering the highly competitive, fast-paced world of rock and roll, he was by definition entering the one art form that relied completely and uniquely on intense, rapid, often nerve-racking collaboration—the thing he had the most trouble with. Soon his new bandmates would discover what the Eldorados had collided with at Syracuse—that Lou could be the sweetest, most charming companion socially, but he was virtually always a motherfucker to work with. His biggest problem, apart from demanding complete control and having a Himalayan ego, was the matter of credit. Just as the Rolling Stones had done when creating their music, the Velvet Underground worked up almost all of their songs collectively. Reed, who composed the simple, inspirational chord structures or sketchy lyrics, was under the impression, however, that he had single-handedly crafted masterpieces like “Heroin,” “Venus in Furs,” “I’m Waiting for the Man,” “Black Angel’s Death Song,” etc. In truth, although Reed undoubtedly supplied the brilliant lyrics and chord structures, the various and greater parts of the music—Cale’s viola; Morrison’s guitar; MacLise’s drumming—were invented by each individually. In short, Reed should have shared the majority of his writing credits with other members of the band. At first, of course, before the question of signing any contract came up, everything was copacetic—since there was nothing to argue about. The group was also under the impression, due to the nature of the material, that no one would ever record or cover their music. In time, however, this vital subject of artistic collaboration, credit, and, most importantly, of publishing rights (which is where the most money is made in rock and roll in the long run) would become the deepest wound in the band’s history of battles.

Still, in early 1965, Angus became a devoted, if crazy, friend to Lou, in the tradition of Lincoln Swados. Angus turned Lou on to the easily available pharmaceutical, methamphetamine hydrochloride, which was the drug of choice of a particularly intense group of visionary seekers centered around Jack Smith, and later, Andy Warhol. Methamphetamine hydrochloride—speed—is a key to understanding what set Reed and Cale’s sound aside from the mainstream of American pop in the second half of the 1960s, which was based more on soft and hallucinogenic drugs.

The tension between these four disparate personalities became the emotional engine of their music. Twenty years later, Reed would vigorously deny that the friction, particularly between him and Cale, was constructive. But this was simply one of his many attempts to write or control his own history. Morrison remembered, “I love Lou, but he has what must be a fragmented personality, so you’re never too sure under any conditions what you’re going to have to deal with. He’ll be boyishly charming, naive—Lou is very charming when he wants to be. Or he will be vicious—and if he is, you have to figure out what’s stoking the fire. What drug is he on, or what mad diet? He had all sorts of strange dietary theories. He’d eat nothing, live on wheat husks. He was always trying to move mentally and spiritually to some place where no one had ever gone before. He was often very antisocial and difficult to work with, but he was interesting, and people were interested in the conflict and some of the good things that came out of it.”

Some of the good things that came out of it were the songs that began to soar out over the gritty, dangerous drug supermarkets next to Ludlow Street from Eldridge to the Bowery. Lou, Sterling, Angus, and John hammered away at songs day in and day out, honing down the ones that would appear on the first Velvet Underground album two years later. According to Cale, “We actually worked very hard on the arrangements for the first album. We used to meet once a week for about a year, just to work on arrangements. I felt when we were doing those first arrangements back in Ludlow Street, ’65, that we had something that was going to last. What we did was unique, it was powerful. We spent our entire weekends going over and over and over the songs. We had no big problem with the work ethic; in fact, we were hanging on to the work ethic for dear life.”

By the spring of 1965, the music began to soar. John Cale remembered these earliest days of playing as their best. Cale contributed his unique electric viola, Morrison his hauntingly beautiful electric guitar, MacLise his ethereal Far Eastern drumming, and Reed his raw lyrics and hard delivery of them. Often the band improvised a riff and Reed simply made up the lyrics as he went along. “He was amazing,” Cale said. “One minute he’d be a southern preacher, then he’d change character completely and be someone totally different.”

“In my head it would be great if I could sing like AI Green,” Reed said. “But that’s in my head. It wasn’t true. I had to work out ways of dealing with my voice and its limitations. I wrote for a certain phrase and then bent the lyric to fit the melody. Figured out a way to make it fit.” In 1965 he was remarkably creative, carving a dark, macabre, Poe-like beauty out of Cale’s orchestration of the band’s musical chaos. “We heard our screams turn into songs,” Reed later wrote, “and back into screams again.”

Meanwhile, Cale, traveling back and forth between London and New York on his classical-scholarship funds, was bringing back the latest singles of the most exciting new British groups—the Who, and the Kinks, with whom they felt some affinity. It was an intensely creative, highly energized moment in rock history, and the band gorged themselves on everything they liked. In fact, Reed, who admired a wide range of musicians from Burt Bacharach to the Beach Boys, insisted that the best popular music should be as artistically recognized as poetry. “How can they give Robert Lowell a poetry prize?” he complained in another essay written the following year for Aspen magazine. “Richard Wilbur. It’s a joke. What about the Excellents, Martha and the Vandellas (Holland, Dozier, Jeff Barry, Elle Greenwich, Bacharach and David, Carole King and Gerry Goffin, the best songwriting teams in America). Will none of the powers that be realize what Brian Wilson did with the CHORDS. Phil Spector being made out to be some kind of aberration when he put out the best record ever made, ‘You’ve Lost That Loving Feeling.’”

Drugs were both a catalyst and inhibitor for the music. “There were no heavy addictions or anything, but enough to get in our way, hepatitis and so on,” Sterling recalled. “I would take pills, amphetamines, not psychedelics, we were never into that. Drugs didn’t inspire us for songs or anything like that. We took them for old-fashioned reasons—it made you feel good, braced you for criticism. It wasn’t just drugs, there were vitamins, ginseng, experimental diets. Lou once went on a diet so radical there was no fat showing on his central-nerve chart … his spinal column was raw!

“We took a lot of downers—that’s what I used to do. We did all sorts of junk. There was just so much going on, you had to keep up with it, that was all. I never got really A-headed out. But if you had two members of the band heavily sedated and the other on uppers, it is gonna affect your sensibilities. They wanted to do slow dirges and I wanted to do up-tempo songs!”

That summer two parallel events catapulted the Warlocks, who also occasionally used the in-your-face drug-innuendo name the Falling Spikes, out of the obscurity of Ludlow Street toward the limelight that would soon illuminate them.

First, through MacLise’s connections in the Lower East Side underground-film scene, the most potent movement of the moment embracing arguably the largest, most intelligent, and creative audience in New York, they were invited to play their rehearsal tapes or sometimes perform live to accompany screenings of the mostly silent underground films by Jack Smith, Ron Rice, Andy Warhol, Stan Brakhage, and Barbara Rubin, which were making a big splash that season. Nineteen sixty-five was the climactic year of the Lower East Side art community and in particularly the underground-film scene. One of the scene’s most outstanding, enigmatic figures, the poet and filmmaker Piero Heliczer, who often screened films at his enormous art factory loft on Grand Street, three blocks from 56 Ludlow Street, first offered the group a venue to play. Soon they were playing regularly at Heliczer’s and other artists’ spaces, sitting behind the film screens or off to the side. The most popular underground-film cheater space at the time was Jonas Mekas’s Cinémathèque, which became the band’s most regular venue. “Center stage of the old Cinémathèque was a movie screen, and between the screen and the audience a number of veils were spread out in different places,” recalled Sterling. “These were lit variously by slide projections and lights, as Piero’s films shone through them onto the screen. Dancers and incense swirled around, poetry and song rose up, while from behind the screen a strange music was generated by Lou Reed, John Cale, Angus, and me, with Piero back there too playing his sax.” Occasionally they would play bare-chested with painted torsos or try to look outrageous in some other way. They gained enthusiastic audiences, among whom Barbara Rubin would become their most influential fan.

Their second breakthrough came in July when they recorded a demo tape at 56 Ludlow Street that included early versions of “Heroin,” “Venus in Furs,” “The Black Angel’s Death Song,” and “Wrap Your Troubles in Dreams.” “‘Wrap Your Troubles in Dreams,’ that’s relentless,” said John Cale. “Lou’s often said, ‘Hey, some of these songs are just not worthy of human endeavor, these things are best left alone.’ He may be right.” The tape also included a song that Morrison later recalled as “Never Get Emotionally Involved with a Man, Woman, Beast or Child.” Cale took the tape over to London in the hope of securing a recording contract with one of the most adventurous British companies (after all, the Who and the Kinks used similar techniques), and there was considerable interest from, among others, Miles Copeland, who would go on to manage the Police.

By the fall, with their music mature and their audience growing, they felt that something was happening. This seemed confirmed in November when they stumbled upon the name they would keep, the Velvet Underground, “swiping it,” as Lou put it, from the title of a cheap paperback book about suburban sex Tony Conrad literally picked out of the gutter and brought to Ludlow Street. The name Velvet Underground seemed to fit perfectly their affiliations and intentions. That same month they got their first media boost when filmed playing “Venus in Furs” for a CBS documentary on New York underground film, featuring Piero Heliczer and narrated by Walter Cronkite. When the prestigious rock journalist Alfred G. Aronowitz offered to manage them, they accepted.

AI Aronowitz, who had an influential pop column in the New York Post and had written extensively about the Beatles, Stones, and Dylan, was an important player on the New York rock scene. “Aronowitz was famous,” wrote one onlooker. “Aronowitz was the man who’d introduced Allen Ginsberg to Bob Dylan and Bob Dylan to the Beatles. He’d known Billie Holiday and Jack Kerouac and Paul Newman and Frank Sinatra. He could get Ahmet Ertegun, George Plimpton, Clive Davis, or Willem de Kooning on the phone. He’d been Brian Jones’s American connection and Leon Russell’s New York guru and the one who introduced Pete Hamill to Norman Mailer. Only Aronowitz could write a rock column in a daily newspaper that’d make the whole country snap to attention.” His interest in the Velvets was a sure sign of impending success.

Suddenly, however, their unorthodox background clashed with their progress. As soon as Aronowitz presented them with their first paying job, opening for another group he managed, the Myddle Class, Angus MacLise, as Lou recalled, “asked a very intriguing question. He said, ‘Do you mean we have to show up at a certain time—and start playing—and then end?’ And we said, ‘Yes.’ And he said, ‘Well, I can’t handle that!’ And that was it. I mean, we got our electricity out of Angus’s apartment, but that was it. He was a great drummer.”

Lou, who put his beloved group before anything and anyone, never forgave MacLise. But as it developed, Angus’s withdrawal set in motion one last chance meeting that would perfectly complete the band. With the Aronowitz date booked for December 11, only days away, Lou and Sterling suddenly remembered that their Syracuse friend Jim Tucker had a sister who played drums and wondered if she might be able to fill in. Cale, horrified by the mere suggestion that a “chick” should play in their great group, had to be placated by the promise that it was strictly temporary. When he acquiesced, Lou shot out to the suburbs of Long Island to audition Moe Tucker. “My brother had been telling me about Lou for a while, because he had known him for a few years before that,” Maureen recalled. “I was nineteen at the time, living at home and had a job, keying stuff into computers. Lou came out to my house to see if I could really play the drums. He said, ‘Okay, that’s good.’”

When she first went to John’s apartment in New York to hear the band play their repertoire, Maureen, whose favorite drummer was Charlie Watts, was knocked out. She could see that Lou was a bona fide rock-and-roll freak, and the whole band was amazing. “When they played ‘Heroin,’ I was really impressed. You could just tell that this was different.”

Maureen’s drumming was a distillation of all the rock and roll that had gone before, and yet, influenced by African musicians, she played with mallets on two kettledrums while standing up. “I developed a really basic style,” she said, “mainly because I didn’t have any training—to this day I couldn’t do a roll to save my life, or any of that other fancy stuff, nor have I any wish to. I always wanted to keep a simple but steady beat behind the band so no matter how wild John or Lou would get, there would still be this low drone holding it together.” Methodical and steady as a person and a drummer, Maureen kept up the backbeat. But, young as she was in comparison to her older brother’s friends, she held her own, rarely keeping her opinions to herself when they mattered. Though bowled over by the Velvets’ music, she was not always impressed with the lifestyle that went along with it. She thought it was crazy for John and Lou to go out and look for firewood to heat their apartment. “It wasn’t very romantic,” she commented later about the flat. “It stank.”

The Velvet Underground’s first job took place at Summit High School in Summit, New Jersey, on December 11, 1965. They were squeezed in between a band called 40 Fingers and the Myddle Class. “Nothing could have prepared the kids and parents assembled in the auditorium for what they were about to experience that night,” wrote Rob Norris, a Summit student. “Our only clue was the small crowd of strange-looking people hanging around in front of the stage.”

What followed the gentle strains of 40 Fingers was a performance that would have shocked anyone outside of the most avant-garde audiences of the Lower East Side. The curtain rose on the Velvet Underground, revealing four long-haired figures dressed in black and poised behind a strange variety of instruments. Maureen’s tiny hermaphroditic figure stood behind her kettledrums, making everyone immediately wonder uneasily whether she was a girl or a boy. Sterling’s tall, angular frame shuffled nervously in the background. Lou and John, both in sunglasses, stared blankly at the astonished students, teachers, and parents, Cale wielding his odd-looking viola. As they charged into the opening chords of the cacophonous “Venus in Furs” louder than anyone in the room had ever heard music played, they rounded out an image aptly described as bizarre and terrifying. “Everyone was hit by the screeching urge of sound, with a pounding beat louder than anything we’d ever heard,” Norris continued. “About a minute into the second song, which the singer had introduced as ‘Heroin,’ the music began to get even more intense. It swelled and accelerated like a giant tidal wave which was threatening to engulf us all. At this point most of the audience retreated in horror for the safety of their homes, thoroughly convinced of the dangers of rock and roll music.” According to Sterling, “the murmur of surprise that greeted our appearance as the curtain went up increased to a roar of disbelief once we started to play ‘Venus’ and swelled to a mighty howl of outrage and bewilderment by the end of ‘Heroin.’”

“Backstage after their set, the viola player was seen apologizing profusely to an outraged Myddle Class entourage for scaring away half the audience,” Norris concluded. “AI Aronowitz was philosophical about it, though. He said, ‘At least you’ve given them a night to remember,’ and invited everyone to a party at his house after the show.”

Observing that the group seemed to have an oddly stimulating and polarizing effect on audiences, Aronowitz advised them to get some experience playing in public by doing a residency at a small club. Four days later they started a two-week stand at the Cafe Bizarre on MacDougal Street in New York’s Greenwich Village. “We played some covers, ‘Little Queenie,’ ‘Bright Lights Big City,’ the black R-and-B songs Lou and I liked—and as many of our own songs as we had,” Sterling reported. “We needed a lot more of our own material, so we sat around and worked; that’s when we wrote ‘Run Run Run,’ all those things. Lou usually would have some lyrics written, and something would grow out of that with us jamming. He was a terrific improvisational lyricist. I remember we had the Christmas tree up, but no decorations on it, we were sitting around busy writing songs, because we had to, we needed them that night!”

This fortuitous opportunity was pivotal for their career. First, since there was so little time between the two dates, they decided to keep Maureen, initially much to Cale’s chagrin. Moe remembered standing in the street with John, who kept saying, “No chicks in the band. No chicks.” Second, at the very time they were playing at the Cafe Bizarre to unreceptive tourists twice a night for $5 apiece per night, the pop artist and entrepreneur Andy Warhol was looking around for a group to manage for a nightclub he had been asked to host by the theatrical impresario Michael Myerberg (who had brought Beckett’s Waiting for Godot to the USA in 1956). Barbara Rubin, for whose film Christmas on Earth the band had played in their previous incarnation, was spending a good deal of time at the Warhol studio, the famous Silver Factory, and thought the Velvets would be the perfect band for Warhol’s upcoming discotheque. She took two of Warhol’s leading talent scouts, the film director Paul Morrissey and the underground film star Gerard Malanga, to see them. Malanga, who has just starred in Warhol’s version of A Clockwork Orange, Vinyl, was an outstandingly handsome young man with a potent sexual aura. Combining the looks of Elvis Presley and James Dean with the long hair of Mick Jagger, Malanga dressed head to foot in black leather and carried, purely for dramatic effect, a black leather bullwhip, which he wore wrapped around the shoulder of his jacket. During the Velvets’ set, Gerard suddenly leapt up from his table onto the empty dance floor. All of the other customers were too terrified by the music to move. Making ample use of his whip, he undulated in a sinister, erotic dance that perfectly illustrated the visceral, throbbing music. The band was dumbfounded by Gerard’s mind-blowing performance. In the intermission Lou and John went over to his table and told him to come back and dance anytime. Instantly spotting a starring role for himself in the scenario, Malanga thought the group would be perfect for Warhol.

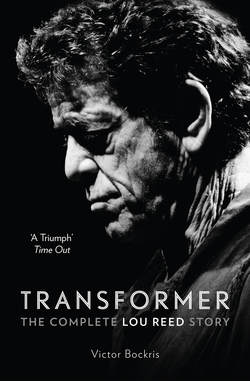

Lou performing in the Paraphernalia footage of Gerard Malanga’s Film Notebooks, 1966. (Victor Bockris)

The following night Malanga returned to the Cafe Bizarre with Rubin, Warhol’s business manager Paul Morrissey, and Warhol himself, accompanied by an entourage including his reigning superstar Edie Sedgwick. They were thrilled by the weird and raucous performance of the Velvet Underground. Not only did the group do the same thing Warhol’s films did—make people uncomfortable—but their name, and the fact that they sang about taboo subjects, perfectly fit Warhol’s program. To top it off, Morrissey was intrigued by the band’s androgynous drummer. After the set Barbara brought the Velvets over to Andy’s table. The curly-haired Lou Reed, with his shy smile, shared a temperament with Warhol. He sat next to the pop artist and the two of them immediately hit it off. “Lou looked good and pubescent then,” Warhol recalled. “Paul thought the kids out on the Island would identify with that.”

Morrissey, who was the most influential person in Warhol’s world after Malanga, was fascinated: “John Cale had a wonderful appearance and he played the electric viola, which was a real novelty; but best of all was Maureen Tucker, the drummer. You couldn’t take your eyes off her because you couldn’t work out if she was a boy or a girl. Nobody had ever had a girl drummer before. She made no movement, she was so sedate. I proposed that we sign a contract with them, we’d manage them and give them a place to play.”

“We looked at each other,” Lou Reed remembered, “and said, ‘This sounds like really great fun.’”