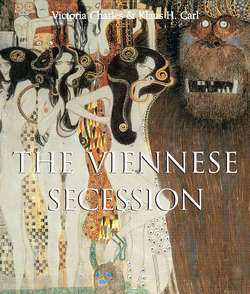

Читать книгу The Viennese Secession - Victoria Charles - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Precursors of the Viennese Secession in Munich and Berlin

Artists of the Berlin Secession

ОглавлениеThree artists, who were enormously popular and had many imitators in 19th century Berlin, need to be addressed first: Ludwig Hoffman (1861–1945), Walter Leistikow (1865–1908), and Max Liebermann (1847–1935). Ludwig Hofmann was both a painter and a designer. His personality and passion for French art gave him the tools to render his art with a truly unique character. The world he shows us in his paintings with visually poetic eloquence is detached from all insufficiencies of life. His figures don’t belong to a specific period or era; they are always young, beautiful and innocent. They bathe, exult, rest, play, or dance. Hoffmann’s paintings are like shallow, pleasant dreams. Certainly, they don’t move the soul deeply, but stroke it tenderly, like music. Nevertheless, they are delightful to behold and a fitting adornment for every monumental room.

A kindred spirit to Ludwig Hofmann is landscape painter Walter Leistikow, who similarly used influences from a specific school of painting – in his case, the Old Dutch masters – to create distinct style of his own. Characterised by a tranquil atmosphere, few muted colours and strong, big shapes, his paintings depicted the melancholic nature of the March of Brandenburg or the endless pastures of the Danish landscape. He, like no other painter before him – with the exception of Karl Blechen (1798–1840), maybe – made the austere beauty of the dark seas and the acheronian forests of the Berlin environs accessible to a larger audience.

Max Liebermann could be the legitimate successor of famous painter Adolph Menzel (1815–1905), whose style is apparent in many of Liebermann’s paintings and drawings. Menzel is counted among the most important artists of German impressionism – if not the most important artist – having drawn inspiration from the old Master Rembrandt and from his contemporary Jean-François Millet, and thus having created an oeuvre that shows obvious nods to the two great artists but is, nevertheless, a coherent and individual achievement in itself.

Liebermann’s first painting, Gänserupferinnen (Women Plucking Geese) (1872), caught the eye of the public and caused general indignation among Berlin’s art critics and enthusiasts, who considered the subject either too mundane or too “dirty”. Liebermann, however, continued in the same vein and painted Konservenmacherinnen (Women Crafting Tin Cans) (1872) and Arbeiter im Rübenfeld (Workers Harvesting Turnips on the Field) (c. 1874). He was also amongst the first German painters to head for the Netherlands in order to study certain overlooked artists like Frans Hals (1580/85–1666), and to capture the unique atmosphere of the country. Initially he focused on specifically “Dutch” motives, as in the paintings Men’s Retirement Home in Amsterdam (1882), Schusterwerkstatt (Cobbler’s Workshop) (1881), or Freistunde im Waisenhaus in Amsterdam (Free Period In An Orphanage In Amsterdam) (1881/1882), while later it was the Dutch coast and its unique light and air that captivated his artistic spirit. Women Mending Nets (1889) and Frau mit den Ziegen (Woman with Goats) (1890) were both created during that time.

Already by 1892, Max Liebermann and Walter Leistikow had created the Vereinigung der XI (Association of The Eleven) and were presiding over the group, which – true to its name – was a group of exactly eleven artists. After the foundation of the Berlin Secession on 2 May 1898, they, being experienced leaders, took over the direction of the newly-found group, too.

Hans Thoma, Solitude, 1906.

Oil on canvas, 82 × 67 cm.

Landesbank Baden-Württemberg Collection.

Max Liebermann, Country House in Hilversum, 1901.

Oil on canvas, 65 × 80 cm.

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin.

Walter Leistikow, Waldstück mit Sandgrube (Corner of Forest with Sand Pit), c. 1905.

Oil on canvas, 30 × 50 cm.

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin.

Other members of the group were Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945), Heinrich Rudolf Zille (1858–1929), Lovis Corinth (1858–1925) and Max Slevogt (1868–1932). Kollwitz worked as sculptor and designer, creating impressive works that were a testimony to her sensitivity and passion for the social problems of the city. She was born and lived in Konigsberg (modern-day Kaliningrad) where she joined the Prussian Academy of Fine Arts and remained a member of the board of professors until the National Socialists deemed her “unacceptable” and removed her from her position as teacher. Her artworks, which could easily be classified as Realism, were dedicated to neglected social topics. The most important of those works are the etching cycles Revolt of the Weavers (1897–1898), The Peasants’ Revolt (1903–1908), and a series of woodcuts entitled Der Krieg (War) (1922/1923). Shortly before the end of the Second World War, she died in the ruins of the nearly destroyed city of Dresden.

Painter, illustrator, and photographer Heinrich Zille, who carried his Berlin nickname “Pinselheinrich” (Paint-Brush-Heinrich) proudly, was a similarly dedicated critic of the low social conditions that plagued the less privileged classes with his precise depictions of the Berlin slums and housing projects drawing attention to their plight. Soon after, the residents of Berlin started calling these parts of the town “Zille’s Milieu” because of the frequent treatment he gave the issue. Zille was a prolific artist who showcased his work in different and creative ways: in satirical magazines such as Simplicissimus and Ulk, on the walls of beer taverns or published in artistic portfolios called Mutter Erde (Mother Earth) (1905) and Zwölf Künstlerdrucke (Twelve Artistic Prints) (1909). His smooth charcoal and crayon-drawings garnered such fame that composer Willi Kollo (1904–1988) and songwriter Hans Pflanzer wrote a song that was later popularised through the interpretations by German chanson singer Claire Waldoff, and later Hildegard Knef. The famous chorus was a homage to Zille’s favourite topic and his familiarity with the “scene”:

Das war sein Milljöh

Das war sein Milljöh.

Jede Kneipe und Destille

Kennt den guten Vater Zille.

Jedes Droschkenpferd

Hat von ihm gehört.

Von N. O. bis J. W. D. —

Das war sein Milljöh.

That was his milieu

That was his milieu

Every pub and distillery

Knows good father Zille

Every coach horse

Heard of him

From N. O. to Jottwede

That was his milieu [loose translation]

Franz von Stuck, Poster for the First International Exhibition of the Association of Visual Artists of Munich (Secession), 1893.

Coloured lithograph.

Museum Villa Stuck, Munich.

Through Max Liebermann’s introduction he joined the Berlin Secession, where he quickly made friends with the other artists, especially Käthe Kollwitz.

Another member from the first Generation of Secession artists was Lovis Corinth, who started his study of the fine arts with genre painter Otto Günther (1838–1884) in Königsberg. Four years after he had started his apprenticeship with Günther he moved to Munich. After serving in the military for a year he lived in Antwerp for a short time before moving to Paris in order to attend the Académie Julian. However the city could not satisfy his restlessness for long. He returned first to Königsberg, moved to Berlin in 1888 and three years later to Munich, where he joined the Munich Secession. Later, he left Munich again when his Salomé was refused for exhibition by a jury of Secession artists. Biblical and mythological themes were the main focus of his works: for example, Home-coming Bacchants (1895), Kreuzabnahme (Deposition from the Cross) (1895), Crucifixion (1897/1898), Salomé (1900), and Der geblendete Simson (The Blinded Samson) (1912). Furthermore, he painted excellent nude studies, intimate portraits, scenes from daily life, and still-lifes. All of his works reveal an unusal amount of creative energy that truly marked Lovis Corinth as an awe-inspiring artist.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента. Купить книгу