Читать книгу The Viennese Secession - Victoria Charles - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

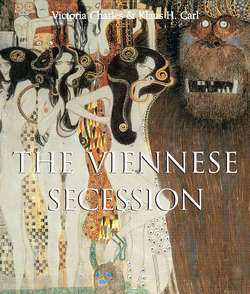

Vienna in the Second Half of the 19th Century

Art in England at the End of the Century

ОглавлениеThe rise of Art Nouveau was no less remarkable in other countries. In England, the popularity of venues such as the Liberty & Co. Department Store, the Merton-Abbey Workshops, and the Kelmscott-Press, which was managed by William Morris (1834–1896) and supplied with designs and ideas by the two painters Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898) and Walter Crane (1845–1915), rose steadily. This trend even reached London’s “Grand Bazaar”, Maple & Co., where the customers were offered Art Nouveau while the house designs fell more and more out of favour.

The main representatives of this new movement of applied art were, already mentioned, William Morris and John Ruskin (1819–1900). John Ruskin – more of a predecessor to the Arts and Crafts Movement – was well known for being a staunch believer in art and beauty, almost to such a degree that his concept of art began resembling a religion on its own. Similarly, Morris was not simply an artisan but also a true artist and poet. His wallpapers and fabrics revolutionised home décor and their success enabled him to build a factory dedicated to the production of these products. Beside his artistic efforts he was also a politically active member of several socialist movements and parties.

Ruskin and Morris were, of course, not the only leading figures of the movement. There was also the architect Philip Speakman Webb (1831–1915) and the painter Walter Crane, who could rightfully be called the most creative interior decorator of his time, possessed as he was with an impeccable sense of elegance. They were a beacon for a whole generation of outstanding architects, designers, decorators and illustrators who flocked to their banner to realise their dreams of a new art together. Their artistic prowess is beyond comparison: like in a pantheistic dream they composed a fragile melody of ornaments that fused flora and fauna into a transcendent whole. This ornament-based art, with its filigreed patterns and arabesques, was reminiscent of the exuberant ornament-artists of the Renaissance. Not by accident either. The English artists intricately studied the elaborate engraving techniques – which today are rather under-appreciated – from the 15th and 16th centuries. In a similar manner they studied the wood, copper and niello artwork of their contemporaries from the Munich school.

Despite using the art of the past as direct inspiration, the designers of the English Art Nouveau never copied it reverently, afraid of creating something new; quite the opposite, they enriched this art with the pure joy of new creation. One simply has to skim through old editions of The Studio Magazine, The Artist, or The Magazine of Art[1] and marvel at the designs for decorative book covers and various other ornamented media in order to see the immense creativity that animated the movement. It is quite fascinating to see how much young talent – among these talented artists were also quite a few girls and women – was unearthed in the art competitions that were organised by The Studio or South Kensington.[2] The new prints, fabrics and wallpapers which changed the traditional way of home décor, created by Crane, Morris and designer Charles Voysey (1857–1941), might have been inspired by patterns seen in nature itself but it also referenced the traditional Oriental and European principles of ornament taught by authentic decorators of the past.

William Morris or Edward Burne-Jones, Light and Darkness, Night and Day (detail from The Creation), 1861.

Stained glass window.

All Saints Church, Selsley, Gloucestershire.

William Morris or Edward Burne-Jones, Heaven, Earth and Water (detail from The Creation), 1861.

Stained glass window.

All Saints Church, Selsley, Gloucestershire.

The architecture in England was clearly dominated by the formal classicism based on Greek, Roman, and Italian models. With the Arts and Crafts movement, England finally rebelled against this conformism and rejuvenated English art. At the frontlines of this revolution were, first, architects like Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (1812–1852) who participated in creating the design of the Houses of Parliament and, later, a group of Pre-Raphaelite artists, who preferred their contemporary art more than the art of the 16th century and the classicism that was so foreign to the English tradition.

Architects were also responsible for reviving old English art by applying the simple, elegant workmanship of 16th and 17th century English architecture from the times of Queen Anne (1665–1714) to contemporary tastes. Old English art was not the only source of inspiration they sought. Given the similarity in climate, manners, and a certain degree of ethnic cousinship, it was only natural for them to use North European influences as well. From the colourful architecture of Flanders to the red brick buildings of Frisia, Denmark, and the north of Germany, they were given a multitude of inspiration.

The majority of these architects did not feel diminished to also work as interior decorators. Quite the opposite – they could not imagine it any other way. How else could it be possible to achieve perfect harmony between the outside and the inside of a house? In the interior they sought the same harmony that was apparent on the outside. With tapestries and furniture they composed an ensemble of shapes, patterns, and muted colours in which every single component was perfectly attuned to each other.[3]

Among the most notable architects were Richard Norman Shaw (1831–1912), Thomas Edward Collcutt (1840–1924), the members of Ernest George’s (1839–1922) office and Harold Ainsworth Peto (1854–1933). They brought back a notion that was missing in the movement: the subordination of all art under architecture. Without this idea it is impossible to develop a distinctive style. We have to thank them for the re-introduction of pastel-décor (from the 18th century), the re-discovery of architectonic ceramics (from the ancient Orient) and finally for brightening the predominantly grey- and brown-shaded colour palette with sea-green or peacock-blue.

The reformation of architecture and applied art in England was only a national phenomenon at first. It might not be immediately apparent in the work of William Morris but his main passion was English art and history. This passion resulted in a return to colours, shapes and patterns which no longer originated from Greek, Roman, or Italian art, therefore constituting a truly English and no longer classical art. Beside wallpapers and tapestries, England now had distinctively individual furniture which was new and modern; the interiors of its houses showcased the decorative composites and colours of the new movement.

Charles Francis Annesley Voysey, Design for Owl Wallpaper and Fabric, c. 1897.

Crayon and watercolour, 50.8 × 40 cm.

Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Aubrey Beardsley, Poster for The Studio, 1893.

Engraving. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Aubrey Beardsley, The Toilet of Salome, drawing from Oscar Wilde’s Salome, 1893.

Line block print, ink on paper.

Private collection.

1

The Studio, The Magazine of Art, and L’Artiste were art magazines that were published in Paris and London. This form of publication had its zenith in the late 19th century, when public interest for applied art was at its highest. Arts et décoration (1897), first published in Paris, is another magazine from this tradition.

2

South Kensington was a name commonly used for the Royal College of Art.

3

This school of architecture that originated in the principles of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (1814–1879) defined the architect as a type of project leader who was responsible for the harmonic mesh of construction, decoration and interior decoration.