Читать книгу David's Sling - Victoria C. Gardner Coates - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

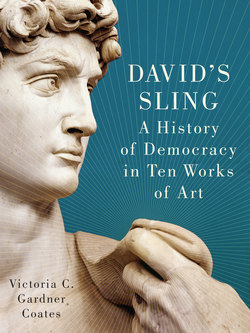

ОглавлениеFor Liberty and Blood

Brutus and the Roman Republic

For liberty and Rome demand their blood And he who pardons guilt like theirs takes part in it.

VOLTAIRE, Brutus

Delphi: c. 540 BC

Titus and Arruns Tarquinius shared a self-satisfied smile as they passed the rows of triumphal monuments lining the road to the ancient shrine at Delphi in central Greece. The beautiful marble and bronze faces of generations of athletes stared impassively at the travelers, secure in their timeless perfection. The aristocratic brothers felt a certain kinship with them, which they did not think extended to their cousin who was traveling with them.

Appearing stupid can be a remarkably smart disguise, and Lucius Junius had it down to a science. His rough face with its heavy beard was a far cry from the polished features of the Tarquin family, let alone the superhuman Greek athletes. His cousins had nicknamed him “Brutus,” or idiot. He plodded quietly behind Titus and Arruns, keeping his eyes on the ground.11

Dio Cassius, Historia Romana 11.10.

The three young Romans had made the long journey to Greece to find out which of them should be the next king of their city. Rome may not have seemed much to rule in those days, with about 35,000 inhabitants and a territory of some 350 square miles. The capital was a cluster of simple clay and wood structures that clung to a group of hills near the Tiber River. While strategic, the location couldn’t function as a port since the river was too shallow to allow the passage of seafaring vessels. At the same time, the proximity to the river meant that floods were a constant menace, and the flatlands were a swamp where disease bred easily. Rome’s neighbors, the Etruscans, considered Rome a rather crude minor power. They preferred to build their cities directly on the coast to facilitate the sea trade, or on more salubrious inland hilltops.

But the Romans were determined. A recent king had drained the swamp by constructing a great sewer, the Cloaca Maxima, to create the dry land for a proper city center. The Romans were so proud of this feat of engineering, the world’s first covered sewage system, that they appointed a dedicated deity, Venus Cloacina, to protect it and built a temple in her honor. They insisted that all number of divine portents foretold a mighty future for their city, which would require a suitably strong ruler.

The obvious candidates were Titus and Arruns Tarquinius, sons of the current king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, or “Tarquin the Proud.” He had assumed the throne after murdering his predecessor (who happened to be his father-in-law), and he wanted to institute a more orderly succession plan.22 Tarquin was a powerful autocrat who expanded Rome’s influence throughout central Italy, but he was not uniformly popular at home. His habit of ignoring the traditional cabinet of advisers to the king, known as the Senate, had provoked the most criticism. Consultation with the Senate, which included men from the most prominent clans, was not a point of law, but the Romans had become accustomed to having a say in how their monarchs governed. Tarquin responded to their grumbling by summarily executing some of the senators.

Livy’s Ab urbe condita libri (History of Rome) records that Tarquin had been attracted to his predecessor’s daughter Tullia, who was inconveniently married to his brother, while Tarquin was married to her sister. Tarquin and Tullia murdered their spouses so they could marry each other, then plotted to overthrow Tullia’s father. When this was achieved, Tullia personally drove her chariot to the place where her father had fallen and ran over his body for good measure. Ab urbe condita 1.47.

As he grew older, Tarquin had come up with a scheme to put the succession in the hands of the gods. He would send his two most promising sons to Delphi to ask Apollo’s oracle which one should be king. To offset charges that the Tarquins were being too presumptuous by assuming that one of their own would be the successor, he sent along his sister’s dullard son Brutus as a token outsider.33 Apollo would know at a glance that this young man was no king.

Livy, Ab urbe condita 1.56.

The cousins had an arduous trip across the Italian peninsula through the lands of hostile tribes on uncertain tracks; the famous roads that would unite a vast empire were centuries in the future. But once they had sailed away from the Adriatic coast and finally reached Delphi, they received a warm welcome. They were wealthy enough to pay the tribute that would allow them to jump to the front of the long line of poor pilgrims who waited for days to consult the oracle and were mostly turned away without gaining an audience.

According to legend, in the mists of time long before the Trojan War, Delphi had been guarded by a monstrous reptile – a dragon known as the Python, with the head of a woman and a habit of eating men alive. Apollo had slain it with his arrows and taken the sanctuary as his own. His priestess, Pythia, was installed in a rocky cave where she could inhale the gases that came up out of the earth from a crack in the floor. In a hallucinogenic trance she would mutter cryptic words that, when correctly interpreted (for another fee), foretold the future.

Modern remains of the theater at Delphi, originally constructed in the 4th century BC.

Titus and Arruns were unnerved by the unblinking glare of the old woman who swayed precariously on a three-legged stool. The cave reeked with the smell of subterranean gas and incense. A priest whispered their query over and over in her ear: Who would next rule Rome?

Pythia stared at the brothers for a long time, then glanced at Brutus, who as usual stood a little behind. Her eyes rolled up into her head and she emitted a stream of gibberish in which only the words “kiss” and “mother” could be understood. Finally she fell silent and slid from her stool to lie still on the floor of the cave. The priest guided the three Romans out to the antechamber, which was richly furnished thanks to the generosity of those whose questions had been answered favorably.

“She chose me!” Arruns and Titus declared simultaneously.

The priest shook his head. Once the requisite tribute had been produced, he informed them that the choice had not yet been made. They should return to their city and the first one to kiss his mother would be the next to rule over Rome.

The young men pondered the oracle’s prediction on their long trip home. Arruns and Titus were focused on how to get to their mother first. As queen, she would be at the front of the party coming out from the city to greet them. They didn’t worry about Brutus, whose mother – a mere younger sister of Tarquin – would be well behind the royal couple.

The brothers raced their horses back to Rome, then sprinted to their mother, knocking her over in the process. Both brothers claimed to have reached her first.

Brutus brought up the rear. When he caught up with them, Arruns and Titus stopped arguing with each other and started laughing at him. His face was covered with mud.

“Don’t tell me,” Arruns jeered. “In your hurry to reach your mother, you fell off your horse! As if you were ever going to get there first.”

Brutus looked down, as if ashamed. But he had not fallen. He had deliberately slipped off his mount the moment it crossed into Roman territory, and pressed his lips to the earth of his motherland long before Arruns and Titus came anywhere near the queen.44

Livy, Ab urbe condita 1.56; Dio Cassius, Historia Romana 11.11.

Rome: c. 510 BC

Rape was not a crime per se in ancient Rome.55 Men dominated society, and women were for the most part a cheap commodity. But the rape of a noblewoman, particularly a married noblewoman, was serious business, involving issues of bloodline and inheritance in addition to honor. It was even more serious when the man in question was a royal prince, as was the case when Lucretia, wife of Brutus’s good friend Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus (a distant relative of the royal family), was raped by Tarquin the Proud’s third son, Sextus.

According to legend, as recounted by Livy, the Roman nation was founded on the abduction and rape of women from the neighboring Sabine clan, which was considered a heroic and patriotic act. Ab urbe condita 1.9.

Like his brothers, Sextus had been brought up with autocratic pretensions. He had also shown himself to be an exemplary liar. Tarquin exploited this talent when he sent Sextus as a double agent to the neighboring town of Gabii, which Rome wanted to conquer. The leading men of Gabii accepted Sextus’s claim that he had betrayed his father to join them, and they made him a general in their army. Having gained their trust by fighting against the Romans, Sextus hatched a plot to murder all the noblemen who had befriended him. Tarquin then sacked the defenseless town.66

Livy, Ab urbe condita 1.52–54.

Sextus rejoined his father’s army and they targeted another unfortunate neighbor. One evening, bored with their maneuvers, the Romans decided to go home and surprise their wives to see how they spent their time while their husbands were away. They found the Tarquinian women dressed in their finest clothes and preparing to have a lavish banquet, while Collatinus’s wife, Lucretia, was working quietly with her maids in her day dress.77

Livy, Ab urbe condita 1.57.

Sextus was annoyed by this display of virtue, which he believed to be just a show to make the royal ladies look bad by comparison. To prove it, he quietly returned to the house of Collatinus the next night and attempted to seduce Lucretia. When it became clear that she would not be persuaded by his promises of love, he drew his sword and threatened her with death. She was still unmoved, so Sextus told her he would kill a male servant along with her and put them naked in bed together so everyone would believe for all eternity that she had been unfaithful. Faced with the threat of perpetual dishonor, Lucretia gave in.

When Sextus was gone, Lucretia sent a message asking her father and husband to come home with one trusted companion; Collatinus chose Brutus. She told them what had happened, and showed them the despoiled marriage bed. Taking her husband by the hand, she begged him through her tears to punish Sextus for his crime.

“Of course,” Collatinus responded, trying to embrace her. “You are blameless – your soul is not responsible for his crime against your body.”

Lucretia pushed him away. “Don’t touch me,” she said. “My body is shamed beyond recovery. It can only be absolved through the proper punishment.” With that, she pulled out a dagger and stabbed herself in the heart.88

Livy, Ab urbe condita 1.58; Dio Cassius, Historia Romana 11.12–19.

Her father and her husband screamed in shock, but Brutus kept his head. Striding forward, he yanked the bloody dagger from the dead woman’s chest. “I swear by the gods,” he shouted, “to expel Superbus Tarquin, his wife, and their disgusting offspring from Rome – by fire, iron, or whatever means I have. Our city shall have no more kings!”99

Livy, Ab urbe condita 1.59.

Rome: 509 BC

The Tarquins were sent into exile in 509 BC. Contrary to expectations, Brutus did not become king of Rome, although he was certainly eligible. He was popular, and – it was quietly known – he was the one chosen by the Delphic sibyl to succeed Lucius Tarquinius Superbus. The prospect of ruling the city as it grew in power and wealth was attractive, but Brutus and his friends had another idea.

Rome was still a backwater around the time the Tarquins were expelled, but the Italian peninsula had many visitors. Rome’s more prosperous neighbors were trading with the Greeks who had settled in Sicily and southern Italy, a region that became known as Magna Græcia, or Greater Greece. Brutus himself had visited Greece as a young man, so he would have been generally aware of what was going on there, including the fledgling development of democracy. Any Athenians the Romans subsequently encountered would have made sure of that.

The Romans were always keenly aware of the cultural superiority of the Greeks (particularly the Athenians), but their appreciation for the Greek model tended toward adaptation rather than flattering imitation. So while Brutus clearly admired a government in which citizens played an active role and no one man dominated, he did not attempt to replicate the Athenian system in Rome. Instead, he forged something specifically Roman: a republic in which citizens voted for the officials who would govern the state, rather than voting on individual pieces of legislation as they did in Athens.

The government established in Rome in 509 BC would change over time and suffer its share of crises and setbacks, but the basic elements endured for more than four centuries – significantly longer than democracy in Athens. The Roman Republic included a revitalized and expanded Senate that was no longer the council of a king, but a formal legislative body that deliberated over and then voted on the laws proposed by smaller regional assemblies of citizens.

Senators served for life and were originally drawn from the patrician class, but later included representatives from the plebs, or commoners, as well as the equites, a class of horsemen with a military origin, just below the patricians. There were between three hundred and six hundred senators, and for official and celebratory occasions they wore distinctive togas to indicate their rank: pure white for the most junior members, while the leading senators had a broad purple border on their togas and special buckles on their shoes.

The Senate was responsible for security and foreign policy, public works, and overseeing the judicial system. Elected officials led by two consuls, and later two tribunes, managed the day-to-day business of the government. In times of emergency a dictator could be appointed, but he was expected to resign voluntarily when the danger passed.

Brutus was already a senator and was a logical choice to be one of the first two consuls, who would serve for a year, alternating the primary power monthly. His partner was Collatinus, the husband of Lucretia. In short order, the new government faced a crisis that threatened to destroy it from within.

The Tarquins had not gone quietly into exile. Instead, they went to their kinsmen in the town of Cære, northwest of Rome, and plotted a return to power. They were furious with Brutus, who they assumed would take the kingship and along with it the substantial fortune they had had to abandon when they fled. For all their bad behavior, the Tarquins were not without supporters in Rome, and they made discreet inquiries to friends in the Senate about the lay of the land. Encouraged by the response, Titus and Arruns approached relatives who were not happy to have lost their royal privileges, promising them a return to the old ways if they supported the Tarquins. A group agreed to help, among them Titus and Tiberius Junius, who were sons of Brutus.1010

Livy, Ab urbe condita 2.3–4.

Titus and Tiberius had, like most, assumed that their father would become king – and that they would hold the same princely position that Titus, Arruns and Sextus had enjoyed. Although pleased that Brutus was the de facto ruler of Rome as consul, they had little use for the democratic system that would end his rule after a year and return him to the status of one among many in the Senate. When Titus and Arruns approached them, the Junius brothers decided they had nothing to lose. If the plot succeeded, the Tarquins would be grateful and reward them. If it failed, they could throw themselves on the mercy of their powerful father, who would be in a position to protect them.

The conspirators made the mistake of discussing their plans in front of a slave, including the fact that they had recorded the details of the plot in a contract that was going to be delivered to the Tarquins at an appointed time and place. The slave reported them to the authorities, the guilty parties were arrested at the rendezvous, and the written evidence of the conspiracy was seized. When confronted, Titus and Tiberius admitted what they had done, assuming that Brutus would put his fidelity as a father over his duty as consul. They anticipated a token period of exile in one of the nearby Etruscan cities, which might actually be enjoyable, after which they would return to their rightful places. They turned out to be poor judges of their father’s character.

Brutus looked sternly at his sons. Their crime, he declared, was treason against the Roman state. He reminded them of the oath they had sworn before him to defend the new liberty of the Roman people from the bribes and promises of kings. Citizenship in the republic was not just a privilege, it was also a weighty responsibility, and true citizens would always put Rome before their personal interests. The consul’s sons had betrayed that trust. The law was unequivocal, and the penalty was death. The traitors were thrown into prison with no further discussion.

On the appointed day of execution, a large crowd gathered on land freshly drained by the Cloaca Maxima, a place that would one day become the Roman Forum. While there were a number of conspirators meeting their fate, everyone was looking at Brutus and his sons, wondering how the consul would handle the event. Many heroes had given their lives in battle for Rome as their patriotic duty; it was quite another thing to deliberately sacrifice two sons in their prime. Titus and Tiberius were stripped and brutally flogged. Some observers reported that Brutus winced and even wept as the boys cried out for him to save them. But he regained his composure, his face settling into an impassive mask. He gave the order for his sons to be decapitated. The slave who had exposed their plot was given citizenship and a rich reward.1111

Livy, Ab urbe condita 2.4.

The assembled Romans were aghast, but also impressed by Brutus’s self-control and willingness to sacrifice his personal happiness for the state. They started to cheer. The consul stood up and raised his hand for silence. “Do not praise me,” he said, “for I am nothing now but a grieving father. Let me go and prepare my house to receive the bodies of my sons.” The crowd quietly parted to let him through.

The Roman Senate confiscated the Tarquins’ property in Rome, which infuriated the family, and they made an attempt to retake the city by force. They marshaled a large Etruscan army that should have outmatched any force the Romans could field.

At first, the battle appeared to be going to the Tarquins. Arruns was in charge of the cavalry, and he confidently observed the smaller force of Roman horsemen. His eye was caught by a group of lictors carrying the ceremonial fasces, the bundle of rods surrounding an axe that symbolized the authority of Roman magistrates. That could mean only one thing: a consul was present. Scanning the lines, Arruns recognized Brutus’s distinctive face. He spurred his mount forward, unable to believe his luck. If he could get rid of his stupid cousin once and for all, the road to Rome would be open. Brutus recognized Arruns as well and rode out to confront him. No words were exchanged as the two cousins speared each other through the chest.1212

Livy, Ab urbe condita 2.5.

Brutus’s death galvanized the Romans, while the Etruscans were demoralized by the loss of Arruns. The battle ended in confusion, but the Romans quickly declared victory and returned to their city to bury their hero. The Tarquinian forces scattered. Tarquin the Proud and his sons were finished for good this time.

Brutus received a magnificent funeral and the entire city mourned him for a year, led by the women of Rome. A large bronze statue was commissioned depicting him brandishing the dagger he had pulled out of Lucretia’s chest as he swore to free Rome of tyrants. It was placed in front of a grand temple to Jupiter, which had just been completed on the sacred Capitoline Hill.

The bronze Brutus drew upon Greek precedents for commemorative monuments and may have been executed by Greek craftsmen who were well versed in casting metal. Still, the generations of Romans who viewed this image of Brutus would have had a very different experience from that of the Athenians who marveled at the beauty of statues such as those adorning the Parthenon. The Greeks specialized in sculpting perfect faces that showed no trace of age or strain, conveying a spiritual superiority unaffected by the outside world. Judging from its art, classical Athens was exclusively populated by young and beautiful people who did not break a sweat, even if they were holding up buildings with their heads or battling monsters. The heroes of the Roman Republic, by contrast, were not transformed into the superhuman counterparts of the classical Greek heroes. Artists began showing them as they were, accentuating rather than airbrushing their individual, imperfect features.

Marble bust of a man, mid 1st century AD, Roman. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The result was the first realistic portraits as we understand them – images that record the unique appearance and individual character of their sitters. In Roman culture, their weathered, lined faces had something higher than mere beauty; they reflected the toil and sacrifice that produced the republic. The greatest ornaments of those portrayed were their heroic deeds, such as Cincinnatus leaving his plow in the field when suddenly appointed dictator to counter an Etruscan invasion and then returning to it immediately after the threat had been repulsed, or Fabius Maximus waging a long campaign to defeat Hannibal and all his elephants in the Second Punic War. The portrait busts of early Romans were treasured by their descendants, who displayed them in their homes as reverence for the forefathers developed into a sort of patriotic religion.

The harsh features of Lucius Junius Brutus had earned him a nickname that was intended to be mocking but wound up as a badge of honor. Indeed, Romans of later generations who wanted to connect themselves to the founder of the republic would claim to resemble his portrait on the Capitoline.1313

Plutarch, Brutus 1.

Rome: March 15, 44 BC

Some 450 years after the statue honoring Brutus was erected on the Capitoline Hill, one of his descendants, Marcus Junius Brutus, picked up a dagger and plunged it into the chest of the most powerful man in Rome. Julius Cæsar was the scion of the noble Julian clan claiming descent from Aeneas, who according to legend had fled Troy as the Greeks annihilated it and then made his way to the Italian peninsula. Cæsar was a brilliant politician and statesman but above all a warrior, campaigning as far afield as Britain and Egypt. The territories under the control of Rome were expanding dramatically, and this growth put a strain on the republican government while a series of civil wars was crippling it from within. When the Senate voted to make Cæsar “dictator in perpetuity” in an effort to restore order, it was a radical transformation of the office that had been devised in the early republic as a temporary expedient for crisis situations.

Most Romans believed that Cæsar was preparing to dissolve the republic once and for all. In desperation, his rivals banded together with the few stalwarts who thought the republic could be preserved, and they plotted his assassination. A key to the conspiracy was the participation of a new Brutus, who would bring the legitimacy of his ancestor’s heroic tyrannicide to this rather underhanded bit of political violence.

Instead of confronting Cæsar in a fair fight, the assassins planned to kill him when he was unarmed at a regular meeting of the Senate on March 15, known as the Ides of March. The defenseless Cæsar was stabbed thirty-three times and bled to death. Marcus Junius Brutus then led the attackers to the Capitoline – where the bronze statue of his ancestor still stood – and declared to the Romans that they were free again.1414

Plutarch, Brutus 14–18.

Cæsar does not seem to have been taking serious precautions to prevent this turn of events. He had dismissed his personal guards some weeks before, perhaps realizing that he would not survive the tumultuous breakdown of the republic. He had lived by the sword and was likely to die by it, but he might be able to arrange things so that his sister’s grandson Octavian could assume power after him and set the Roman world to rights.

Silver denarius minted for Marcus Junius Brutus, 43–42 BC. The reverse shows the dagger that Lucius Junius Brutus pulled out of Lucretia and the dagger that Marcus used to kill Cæsar.

Octavian eventually did just that, but only after decades of bloody and destructive conflict to subdue rival claimants to power – beginning with the dispatching of Brutus and his co-conspirators, and culminating in the defeat of Mark Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC. It was becoming clear that the system fashioned for a small city-state was not equal to governing a sprawling empire. But even as Octavian restructured Rome’s government – and acquired an imperial title, Augustus – he was mindful of the power of the Roman past.

The deeds of the republic’s heroes had been reverently passed down, becoming more awe-inspiring with each generation. Their rigorous moral code and self-sacrifice stood in stark contrast with those who had mired Rome in civil war, from Sulla to Mark Antony. They even looked different, as their rough faces – immortalized in official portraits and innumerable private busts lining the shelves of upper-class homes – gave a mute reproach to their effete descendants who swathed themselves in luxuries imported from Egypt and Byzantium.

For Titus Livius, a scholar and distant cousin of Augustus’s wife, Livia, those heroic stories were not mere legends. They were proof of Rome’s early greatness, which could serve as the foundation for even greater achievements under Augustus and his successors. Following the example of the Greek historians Herodotus and Thucydides, he embarked on a sweeping study of Rome’s history from its origins to his own time. In forty years of writing, he produced a massive work organized into 142 scrolls, titled Ab urbe condita libri, “Books from the Founding of the City,” but more commonly known as The History of Rome.

In his introduction to the history, Livy advised his contemporaries to look back to their city’s origins for the keys to their own character. Despite all the recent bloodshed and upheaval, he saw a grand symmetry in Roman history, from the violence surrounding the first Brutus at the birth of the republic, to a rebirth after the equally violent killing of Julius Cæsar by the second Brutus. Even though Livy was intimate with the newly imperial Julian family, who viewed Cæsar as their divine primogenitor, he rather boldly framed the act of the second Brutus as justified by fears that Cæsar was trying to establish one-man rule.1515 Livy’s narrative proved compelling, and The History of Rome was widely read and copied, becoming an authoritative source book for subsequent historians from Tacitus to Edward Gibbon. Though many of Livy’s later chapters were lost in the eventual breakup of the Roman Empire, the early ones survived, and generations to come would be fascinated by his harsh yet heroic telling of the story of Brutus and the founding of the Roman Republic.

Livy, Periochæ (fragments of Ab urbe condita, from Book 116, http://www.livius.org/li-in/livy/periochae116.html.

Palazzo Carpi, Rome: 1550 AD

The home of a member of the Roman Inquisition might not seem like a comfortable place for someone who had just been exonerated of a heresy charge, but to a man of Ulisse Aldrovandi’s inclinations, Cardinal Rodolfo Pio da Carpi’s palace in Rome was irresistible. It was stuffed with every manner of collectable, from gems and minerals to prized antique marbles to Renaissance canvases by masters such as Raphael, not to mention one of the finest libraries in the city.

Aldrovandi was a polymath who would later be renowned for his study of natural history and his specimen collections. During his months of house arrest in Rome waiting for his trial, he became keenly interested in the city’s ancient heritage – which was only natural for someone named Ulisse after the hero of Homer’s Odyssey (with a brother named Achilles). Cardinal Pio da Carpi was an avid collector of antiquities, and he knew that Aldrovandi was taking notes on the best collections of classical sculpture in Rome for a publication on the subject. Given how quickly great collections were generally sold after their owner died, inclusion in a catalogue to preserve at least the memory of a collection would have been highly desirable.

Aldrovandi had already visited the cardinal’s exquisite villa on the Quirinal Hill and explored the exceptional array of antiquities housed there – a collection so fine in a place so beautiful that he had declared it an earthly paradise.1616 The Quirinal had been part of the city proper in ancient times (as it is today), but in 1546 it was more suburban, almost rural. Over the course of the thousand years since the Western Roman Empire had ceased to exist, the city had slowly contracted. With aqueducts cut off and drains clogged, Rome became marshy and unhealthy, reverting to a set of villages surrounded by the rotting remains of a glorious past. Cattle were put to pasture in the Forum, the Colosseum was used as a stone quarry, and the temple complex on the Capitoline crumbled away. Countless treasures had vanished without a trace, among them the bronze statue of Brutus, which for centuries was known only from accounts in ancient texts.

Ulisse Aldrovandi, Le antichità de la città di Roma (1556), 299.

Marcus Junius Brutus (so-called, now generally identified as Agrippa Postumus), 1st century AD.

It would have taken less than an hour to walk from the cardinal’s villa on the Quirinal to his palazzo in the heart of town, close to the Tiber. While the large-scale antiquities were stored at the villa, Pio da Carpi kept many smaller pieces, notably portraits, in the palazzo. He led Aldrovandi through two rooms packed with heads of emperors and their families, including Carcalla, Agrippina, Julia (daughter of Titus), and Septimus Severus, as well as several Alexander the Greats and a fine Philip of Macedon. Aldrovandi dutifully noted the identifications when known, and scribbled “non conosciuta” in his notebook when they were not.

Both men paused respectfully to gaze up at a marble bust with a Latin inscription that had pride of place over the door leading out of the second room.

“Not only is he beautiful, it is a most rare piece,” said the cardinal. “You recognize him, of course?”

“Of course. The second Brutus. Marcus Junius. And the epitaph – is it a parent lamenting that faithfulness to the surviving offspring prevents her from sharing death with a lost child?”

“Yes indeed. I like to think that Rome felt that way about Brutus, her beloved son – that she would have liked to die with him as a republic but had to continue on as an empire for the sake of her people.”1717

Aldrovandi, Le antichità de la città di Roma, 205–6.

They proceeded into smaller rooms with still more treasures, including busts of Hadrian and Lucius Verus as well as modern portraits of Pope Paul III and Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor. Scattered throughout were innumerable antique fragments – hands, arms, heads, legs, feet. Finally the two men arrived in a study with no fewer than seventy-six portraits. Aldrovandi quickly fixed his attention on one that stood out from the crowd.

“That’s a recent acquisition,” the cardinal told him. “You might find it interesting.”

In fact, Aldrovandi was stunned. Most surviving ancient statuary was marble, with the original paint and ornamentation long since worn away to leave a uniform whiteness and blank eyeballs that appeared blind. Here was a bust made of rich, dark bronze, with eyes of inlaid glass and ivory that gave the impression of a piercing gaze from the past directly into the present.

“That is no emperor,” observed Aldrovandi as he inspected the rough hair and lined features. Images of emperors from Augustus to Constantine had been reproduced over and over again. While they depicted individual traits, they also tended to represent the subject as young and serene regardless of his age or condition when the portrait was made. In contrast, this austere face was that of a man who had been aged by hardships; yet it could be assumed that he had triumphed over them to merit the honor of such a costly portrait.

“In my opinion,” Pio da Carpi said, “it can be only one man. The man who was chosen by Pythia to rule Rome. The man who pulled the dagger from Lucretia’s beautiful breast. The man who swore to banish the tyrants from the city and ordered the execution of his own sons when they betrayed the republic. His harsh story is written on this face as clearly as it is in the pages of Livy.”

“Where was it found?” asked Aldrovandi.

“I can’t be positive,” the cardinal admitted, “but I was assured it was discovered on the Capitoline.”

A number of things had recently been unearthed in that location. About ten years earlier, Pope Paul III had ordered a full rebuilding of the government buildings on the Capitoline Hill. Rome’s already deteriorating condition had been further degraded in 1529 when Protestant German troops commanded by Charles V – His Most Catholic Majesty – captured it after a long siege, sent Pope Clement VII fleeing for his life, and then spent months occupying and sacking the city. The once grand Capitoline was in a sad state, with the medieval palace of the senators (by then a ceremonial title) awkwardly sandwiched between the magistrates’ building and the Church of Santa Maria in Aracoeli (Saint Mary at the Altar of Heaven). While all these structures stood on the foundations of significant ancient Roman buildings and filled important civic and religious functions, they were architecturally undistinguished. The highlight of the complex was the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius standing at the center of the hilltop, but it was frequently obscured by Rome’s boisterous central market.

Paul III commissioned a whole new urban space from Michelangelo Buonarroti, who had moved to Rome after the fall of the Florentine Republic in 1529. Michelangelo created a harmonious plaza by encasing the existing buildings in elegant classical-style architecture. The scrubby ground was cleared and leveled, and a ceremonial staircase flanked by paired ancient statues created a suitable entryway. Marcus Aurelius retained his place of honor, now framed by the elaborate starlike pattern that Michelangelo designed for the plaza pavement. As Michelangelo’s vision took shape, Christian Rome finally appeared to be rivaling the ancient city.

View of the Capitoline Hill before Michelangelo’s restoration, c. 1500.

The Capitoline Hill after Michelangelo’s restoration in 1536–46.

Étienne Dupérac after Michelangelo, piazza on the Capitoline Hill, 1568.

Arial view of the Capitoline Hill after Michelangelo’s restoration.

The heavy construction work unearthed an abundance of ancient artifacts, some of which found their way into the collection of their rightful owner, the pope, while many items were offered on the open market. The antiquities trade in Renaissance Rome was a brisk but shady business. Dealers and collectors alike had their favored “runners” who would alert them when a sensational find was made. Everyone knew that relics of the Roman past once considered rubbish could now fetch a handsome price. Farmers in their fields who had never heard of Julius Cæsar were on the lookout for anything from coins to statues. It paid to be deliberately vague when asked where something was found, since other treasures were likely to be lurking nearby, and there might be troubling issues of ownership. Cardinal Pio da Carpi did not ask too many questions.

“If you look closely,” he said, pointing to the neck of the bust, “you can see that the head was broken off its base at some time. The man who sold it to me admitted he had attached it to a different base. It may have originally had a full body.”

Aldrovandi knew his Livy well enough to understand that a realistic bronze portrait found on the Capitoline could well be – indeed, should be – that of the legendary founder of the Roman Republic. He quickly sketched the head in his notebook and labeled it BRUTUS.

The cardinal was gazing out a window, his head turned slightly in a pose that echoed the ancient bronze.

“I swear I see a resemblance,” said Aldrovandi, trying not to sound too obsequious. Their features were remarkably similar, and Rodolfo Pio da Carpi did come from an old Roman family. Who knew how far back his lineage went in the city?

Cardinal Pio di Carpi died in 1564, and in his will he donated the bronze portrait now universally known as Brutus to the new museum being organized in the judiciary building on the Capitoline.1818 A century earlier, Pope Sixtus IV had assembled some important antiquities in Rome and put them on display in the building’s portico – in effect creating the world’s first public art museum. During Michelangelo’s renovation, the collection was moved inside and displayed formally, and more objects were added. Images of emperors abounded, including the colossal fragments of Constantine and the equestrian Marcus Aurelius. But there were also much older pieces, such as the Etruscan “She-Wolf,” depicting the fierce beast of legend that nurtured the abandoned twins, Romulus and Remus, who went on to found Rome.

From this time on, the actual identification of the portrait ceased to matter until the twentieth century, when it was questioned—throwing the bust into a sudden eclipse from which it has yet to emerge. But for four hundred years it was firmly believed to be the great man celebrated by Livy, and the features were uniformly read as reflective of Brutus’s unyielding dedication to republican principles.

Francesco Salviati, Cardinal Rodolfo Pio da Carpi, c. 1540.

Brutus (so-called), c. 300 BC.

Even among such treasures, the Brutus was clearly iconic. Pio da Carpi thought it should be returned to the site where he believed it had originally stood, and it was joined by his marble head of Marcus Junius Brutus in a display designed to commemorate the family’s heroic deeds permanently on the Capitoline.

* * *

Paris: 1798 AD

Napoleon Bonaparte found himself the undisputed ruler of Italy in 1797. Reversing the progress of Julius Cæsar, who had conquered Gaul for Rome, he had come south over the Alps and waged war in northern Italy for two years. The fiercest resistance had come from Pope Pius IX, who tried to defend the Papal States in the center of the peninsula, but capitulated after a series of decisive French victories. The seemingly immortal Venetian Republic would follow suit a few short months later. From his headquarters in Tolentino, the French general dictated his terms.

The resulting Treaty of Campo Formio shocked the civilized world. In addition to claiming territory in Italy and demanding an enormous sum of money, Napoleon required that the pope surrender the finest ancient and modern cultural treasures of Rome to be transferred to the Musée Napoléon. According to Article 8 of the treaty, a designated commission of experts would select the works and oversee their removal. That commission was given broad latitude to make its choices, as only two objects were specified: the bronze bust of Lucius Junius Brutus and the marble bust of Marcus Junius Brutus from the Capitoline Museum.

“When they arrive,” Napoleon remarked to his favorite painter, Jacques-Louis David, “we can create the greatest museum in the world here in Paris, at the Louvre.” It was still not entirely clear what was coming from Rome in the long convoy of carriages, but they knew the Apollo Belvedere was in the priceless cargo, as well as Raphael’s great last painting, The Transfiguration. And Napoleon wasn’t finished – he was working on a plan to detach Raphael’s frescoes from the walls of the Vatican and dismantle Trajan’s Column so that even these seemingly permanent denizens of Rome could be transported to Paris.

“You know your Brutus is coming?” Napoleon said to David. “I made them put that in the treaty.”

David nodded, wishing as always that the general would sit still for his portrait. The artist’s esteem for the founder of the Roman Republic was well known – he had been in Rome working on a painting of The Lictors Returning to Brutus the Bodies of His Sons for Louis XVI when the revolution broke out in France.1919 David brought it with him back to Paris, where it was a sensation at the 1789 Salon. Begun for a monarch, the picture became an icon of the revolution as Brutus’s willingness to sacrifice his own family in the service of Rome was invoked to justify the Reign of Terror. David’s painting was used as a backdrop for a revival of Voltaire’s play Brutus in 1791, the staging of which also included a copy of the Capitoline bust from David’s personal collection. Now it was on public display in the Louvre.

See image on page 149 below.

“When the bronze arrives,” continued Napoleon, “we will compare your painting to the original and see how well you captured the likeness. I expect you had an easier time with him than with me. And you will have to help me figure out where to put Brutus.”

The Brutus had an eventful visit to Paris. Besides being displayed with David’s painting, it was paraded through the streets on the anniversary of the fall of Robespierre. If David resented this celebration of the execution of his former friend and political mentor, he kept quiet about it. Shortly thereafter, at Napoleon’s request, the painter selected a prime spot for the bust at the Tuileries Palace, which had been home to the kings of France but would now house Napoleon and his wife, Josephine. Napoleon was savvy enough to realize that republican eyebrows would be raised when they made this move; but who could accuse the Bonapartes of imperial tyranny, he reasoned, if they had Lucius Junius Brutus watching over them?2020

Louis Antoine Fauvelet de Bourrienne, Memoirs of Napoleon Bonaparte, ed. R. W. Phipps (1891, 2008), vol. II, 7–8. The Brutus was returned to Rome after the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

Jean-Jérôme Baugean, The Departure from Rome of the Third Convoy of Statues and Works of Art, 1798.

The Basilica of St. Mark, Venice, 1084–1117.

1 Dio Cassius, Historia Romana 11.10.

2 Livy’s Ab urbe condita libri (History of Rome) records that Tarquin had been attracted to his predecessor’s daughter Tullia, who was inconveniently married to his brother, while Tarquin was married to her sister. Tarquin and Tullia murdered their spouses so they could marry each other, then plotted to overthrow Tullia’s father. When this was achieved, Tullia personally drove her chariot to the place where her father had fallen and ran over his body for good measure. Ab urbe condita 1.47.

3 Livy, Ab urbe condita 1.56.

4 Livy, Ab urbe condita 1.56; Dio Cassius, Historia Romana 11.11.

5 According to legend, as recounted by Livy, the Roman nation was founded on the abduction and rape of women from the neighboring Sabine clan, which was considered a heroic and patriotic act. Ab urbe condita 1.9.

6 Livy, Ab urbe condita 1.52–54.

7 Livy, Ab urbe condita 1.57.

8 Livy, Ab urbe condita 1.58; Dio Cassius, Historia Romana 11.12–19.

9 Livy, Ab urbe condita 1.59.

10 Livy, Ab urbe condita 2.3–4.

11 Livy, Ab urbe condita 2.4.

12 Livy, Ab urbe condita 2.5.

13 Plutarch, Brutus 1.

14 Plutarch, Brutus 14–18.

15 Livy, Periochæ (fragments of Aburbe condita, from Book 116, http://www.livius.org/li-in/livy/periochae116.html.

16 Ulisse Aldrovandi, Le antichità de la città di Roma (1556), 299.

17 Aldrovandi, Le antichità de la città di Roma, 205–6.

18 From this time on, the actual identification of the portrait ceased to matter until the twentieth century, when it was questioned—throwing the bust into a sudden eclipse from which it has yet to emerge. But for four hundred years it was firmly believed to be the great man celebrated by Livy, and the features were uniformly read as reflective of Brutus’s unyielding dedication to republican principles.

19 See image on page 149 below.

20 Louis Antoine Fauvelet de Bourrienne, Memoirs of Napoleon Bonaparte, ed. R. W. Phipps (1891, 2008), vol. II, 7–8. The Brutus was returned to Rome after the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.