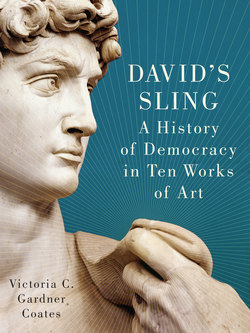

Читать книгу David's Sling - Victoria C. Gardner Coates - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSafeguard of the West

St. Mark’s Basilica and the Most Serene Republic of Venice

Once did She hold the gorgeous East in fee, And was the safeguard of the West: the worth Of Venice did not fall below her birth, Venice, the eldest Child of Liberty.

WILLIAM WORDSWORTH

On the Extinction of the Venetian Republic

Constantinople: April 15, 1204

The old Venetian nobleman ran his hands over the bronze horses as if he were taking the measure of living animals, something he had done innumerable times as a rider. They had been made with such skill that he seemed to feel veins and muscles under their metal skin.

“I saw them when I was here before, and I still had my vision,” he said. “It must have been thirty years ago.”

Enrico Dandolo remembered well his previous visit to Constantinople, the gleaming imperial city on the Bosporus with its wealth of ancient and beautiful monuments, as well as its fantastic natural port, known as the Golden Horn. The skyline was dominated by Hagia Sophia, the Church of the Holy Wisdom. Originally commissioned by Constantine in the fourth century, the building had been destroyed in a riot in 532 AD and then completely rebuilt by Justinian. The emperor had imported rich materials from all over his realm and employed a military engineer to design a gigantic dome soaring over the open central space, appearing to defy the laws of physics.

Dandolo had been in Constantinople in 1172 as a diplomatic representative of his native Venice. Relations between the maritime republic and the Byzantine Empire were severely strained at that time – a year earlier, the emperor Manuel I Comnenus had ordered that all Venetians in Constantinople be arrested and their property confiscated. Some ten thousand people would remain in prison for a decade. The Venetian military response was a disaster, and Dandolo was sent to try to arrange a settlement.

The Horses of St. Mark’s.

It was a hopeless cause. The Byzantines had no reason to negotiate with the Venetians and treated them with a truly imperial scorn. The visit went so badly, in fact, that there was a rumor that Manuel had the Venetian envoy blinded. This was not the case; Dandolo was already beginning to lose his sight to cortical blindness. His mission to Constantinople was nonetheless a grim experience, leaving him with the unshakable impression that the Byzantines were arrogant and vicious, and that their Orthodox Christianity had the tinge of heresy.

Three decades later, the situation was dramatically different. Constantinople burned after a brutal sack at the hands of crusaders under Dandolo’s command. He had been the elected doge of Venice for twelve years, and now he was also the master of Constantinople. In his nineties and stone blind, he remained a man of tremendous energy. Dandolo quickly exerted control over the city and surrounding territories, but found time to inquire after the four horses that caught his notice so long ago. Countless other precious artworks were ruined in the mayhem. The great Byzantine historian Niketas Choniates lamented how “barbarians, haters of the beautiful” had destroyed “marvelous works of art” and converted them into “worthless copper coins.”11 The bronze horses, however, were kept safe on the doge’s orders.

O City of Byzantium: Annals of Niketas Choniates, trans. Harry J. Magoulias (Wayne State University, 1984), 358.

No one knew exactly when the horses had been made, or even where, but there was a long tradition that they had been part of a massive importation of artworks when Constantine turned the city known as Byzantium into the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire. Even in this “Queen of Cities,” renowned for the beauty of her art and her women, the horses were among the choicest of treasures.

Spirited yet poised, natural yet more perfect than any earthly animal, they embodied the ideal of a horse. They also seemed interconnected, as if conversing with each other. They were covered not with the heavy gilding typical of statues from late antiquity, but with a translucent gold wash that gave their bronze surface the reflective quality of a well-groomed horse.

Dandolo rested his hand on the neck of one statue. “Morosini!” he shouted, although the man was standing right beside him.

“Yes, my lord?”

“Crate them, and get them out of this hellhole as quickly as possible. Take them safely back to Venice.”

“Of course.” Domenico Morosini welcomed the task. Himself the descendant of a doge, he had ambitions of his own, and carrying out Dandolo’s orders was a good place to start. “If I may ask, where do you want them to go?”

“To the church of Saint Mark, of course.”22

Charles Freeman, The Horses of St. Mark’s: A Story of Triumph in Byzantium, Paris and Venice (Overlook Press, 2010), 90–95.

The Northern Adriatic: Late Antiquity

The imperial system that had spread Roman rule across the Mediterranean region was failing. Beset by economic and political dysfunction within and by aggressive Germanic tribes outside its borders, the empire could no longer defend its Italian heartland, let alone hold on to its farflung provinces.

At first, the threat had seemed manageable; after all, the Romans had been battling Germans for centuries. (A popular Augustan-era general was called “Germanicus” in honor of his victories over them.) The dynamic began to shift around 251 AD when the emperor was killed by Goths, a branch of the Germanic peoples. Isolated victories turned into a sustained campaign. By the end of the third century, the Romans were abandoning territory to Goths who were settling in large numbers within the empire’s boundaries.

Facing both external and internal pressures, the Romans tried an administrative division of the empire into four parts – two eastern and two western. After Constantine gained control over the whole empire, he moved his capital east in 323 to the ancient city of Byzantium, which he rebuilt and renamed after himself. He showered treasures onto Constantinople, including artworks from all over the empire and relics of all twelve of Jesus’ disciples, in keeping with his conversion to Christianity. Rome was hardly abandoned, for Constantine pursued ambitious building projects there also. He commissioned a triumphal arch beside the Colosseum, and an enormous legislative building in the Forum that housed a forty-foot statue of himself. He initiated an extensive program of church building including the original St. Peter’s Basilica. But power was shifting to Constantinople, which would be the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire when the division resumed after Constantine’s death and then became permanent, well before the last Western Roman emperor was deposed in 476 AD.

Twenty-four years earlier, Attila the Hun had left a trail of devastation through Italy, sacking and razing many towns. Pope Leo the Great famously led a delegation to meet with Attila and plead or negotiate for an agreement to spare Rome.33 There had been no such reprieve for Aquileia, a once-prosperous city in what is now the Veneto region at the northern tip of the Adriatic Sea.

Raphael would commemorate this event in a fresco. Various reasons have been given for why Attila withdrew and left Rome untouched, but the reprieve was temporary—the city was sacked by the Vandals a few years later.

Survivors from the destruction of Aquileia sheltered miserably on an archipelago of small islands in a nearby lagoon. Eventually they began returning to the mainland, until a new scourge would send them fleeing back to the lagoon. City gates could not hold back barbarians, but the expanse of water separating the islands from the coast proved an effective defense. The island dwellers appear to have cultivated a distinctive kind of society. In 523, the historian Cassiodorus wrote of them that “rich and poor live together in equality. The same food and similar houses are shared by all; wherefore they cannot envy each other’s hearths and so they are free from the vices that rule the world.”44

Cassiodorus, “Senator, Praetorian Praefect, to the Tribunes of the Maritime Population,” The Letters of Cassiodorus, trans. Thomas Hodgkin (1886), 517, quoted in Frederick C. Lane, Venice: A Maritime Republic (Johns Hopkins, 1973), 3–4.

The worst of the serial threats to the Veneto region came in 568, when the Lombards crossed the Alps and began conquering northern Italy (including the territory around Milan that is still known as Lombardy). Unlike the nomadic Huns, the Lombards were there to stay, and they made a name for themselves by brutalizing landowners who resisted them. To those taking refuge on the islands, it must have seemed prudent to stay there for good. They remained nominally subject to the Eastern Roman Empire until the Lombards finished off the vestiges of Byzantine power in that region in 751.

By then, the island dwellers were forming their own government. On the mainland, Lombard dukes gathered vassals around themselves and sired traditional dynasties, but something different happened out on the lagoon. The settlement that was becoming Venice had a duke, who was called the doge, but he appears to have been an elected official from early times, at least since the Byzantine overlordship came to an end.

Alexandria, Egypt: 828 AD

The Sassanid Persians had little use for the rich cultural history of Alexandria, which was founded by Alexander the Great and was his burial place. They obliterated what remained of its famous library shortly after conquering the city in 642 AD. As adherents of the rapidly spreading religion of Islam, they had an equal contempt for Alexandria’s Christian tradition, inaugurated by Mark the Evangelist, who was martyred there in the first century. As far as the Persians were concerned, Alexandria was an asset to be milked for resources that would fuel additional conquests.

One day in January 828, the customs officials paid little attention to the two Venetian merchants asking permission to load a large basket onto their galley and sail out of Alexandria’s spectacular natural harbor. The merchants stank and whatever they were carrying smelled even worse. When they uncovered the basket to reveal layers of rotting pork, the Muslim officials drew back in disgust, murmuring “Kanzir, kanzir,” their term for the unholy meat. They were not about to contaminate themselves over these infidels.

The Venetians heaved a sigh of relief as their trireme set sail north into the Mediterranean. Stowed in the barrel under the layers of pork was a religious treasure beyond price.

The veneration of relics – physical remains of Christ, his followers and the many faithful who were martyred under Roman persecution – dated to the time of Constantine’s mother, Saint Helena. She had traveled to the Holy Land and, according to legend, discovered there the True Cross and the veil that Saint Veronica used to wipe the Savior’s face while he was carrying the cross to Gethsemane (both of which are still preserved at St. Peter’s Basilica). Pilgrims by the millions braved arduous travel in the dangerous conditions of early medieval Europe to visit holy relics in Rome. Indeed, as the city was drained of political power and shrank to little more than a village, tourism became its main industry.

While Rome and Constantinople abounded in sacred relics, Venice had almost none. The city had been founded well after the time of the early Christian martyrs, and the first settlers had more pressing things to worry about. But the situation was changing by the ninth century; what had started as a refugee encampment was growing in stature and significance. Previously busy ports, notably the one at Ravenna (which had briefly replaced Rome as the capital of the beleaguered Western Roman Empire), silted up and became unusable. Venice was the obvious alternative, and so it prospered.

The city caught the attention of both Charlemagne, who was reviving a Western “Roman” empire at the beginning of the ninth century, and the emperor Nicephorus I in Constantinople, who considered himself the sole legitimate heir to any territories of the old Roman Empire. In the course of their wrangling, diplomatic and otherwise, Venice was not devastated by either imperial army as had seemed likely. Instead, a treaty between Charlemagne and Nicephorus in 811 established the independence of the Venetian territories between the Western and Eastern powers, a unique status that shaped its identity from that time on. For centuries, the “Holy Roman Emperor” in the West would coexist uneasily with the Byzantine emperor in the East, sparring over everything from religious dogma to dominion over old Roman imperial lands. Meanwhile, Venice was able to develop as an autonomous polity with ties to both East and West.

When Agnello Participazio was elected doge in 811 after valiantly defending Venice from a siege by Charlemagne’s son Pepin, he found both an opportunity and a challenge. The city was becoming a significant power, but one that was limited by its physical plant – a series of small, scraggly islands that flooded regularly and had no level surface on which to build large structures. Fortunately, Participazio was a man of vision who had the trained engineers on staff to carry out his plans. Wood was plentiful on the mainland, and a program was devised to harvest trees and drive the trunks into the soft subsoil of the lagoon so close together that their level tops made a solid surface. Slowly, thousands and then millions of tree trunks were driven into the lagoon, and Venice took form.

Map of Venice, Civitates Orbis Terrarum, 1572.

If the terrain was a handicap, Venice’s situation as a nexus between East and West was a great advantage, and the Venetians capitalized on it in trade agreements not only with Constantinople but also with Damascus and Alexandria. Venetians had to be excellent sailors to survive, so merchant vessels quickly multiplied and fanned out across the Mediterranean Sea. Goods of all sorts began to flow through the city – first salt and fish, then textiles and dyes, and finally spices, arms and slaves. Muslims from the East and Russian heathens from the north were packed into ships and brought to market on the Rialto; Christians were technically off-limits. Advances in galley design resulted in ships that could sail year-round, not just in the summer, and the volume of trade increased accordingly.

The Venetians who sailed out of Alexandria with their precious basket filled with human remains were under the orders of Agnello Participazio’s son Giustiniano, who had forcibly ousted his father, then his brother, to become the doge himself in 827. As ambitious as he was ruthless, Giustiniano was determined to make Venice into the dominant city in Italy – in short, the new Rome.

Rome was not then in much of a position to contest the rise of Venice. The Eternal City, repeatedly sacked by invading tribes, was almost derelict. But as the seat of the pope, Saint Peter’s heir, Rome was still the center of Western Christendom. In this respect at least, Venice was a very poor cousin. Agnello Participazio had made a start in elevating the city’s religious profile by renovating the old convent of San Zaccaria, and in honor of this project the Byzantine emperor Leo V had sent relics – some said the whole body – of Saint Zacharias to Venice from Constantinople.55

Saint Zacharias, the father of John the Baptist, was martyred during the Massacre of the Innocents when he refused to reveal the hiding place of his young son. His remains are also rumored to be in Istanbul, Jerusalem and Azerbaijan.

Giustiniano set his sights higher. According to local legend, the Evangelist Mark, after serving Peter in Rome, had come to establish the church in Aquileia. During this period he translated his Gospel from Hebrew into Greek, and it was widely distributed – marking the first time the story of Jesus was available in what was the international language of the time. In the course of his travels, Mark paused at the uninhabited islands that would one day become Venice. There he had a dream that an angel appeared to him and said, “Pax tibi, Marce, evangelista meus. Hic requiescat corpus tuum.” (Peace be with you, Mark, my Evangelist. Your body will rest here.)66

Andrea Dandolo, Chronica per extensum descripta, cited in John Julius Norwich, A History of Venice (Knopf, 1982), 28.

This experience does not seem to have encouraged the Evangelist to linger. He went on to Rome, and then to Alexandria, where he was martyred and interred for some centuries. But the legend persisted connecting Saint Mark with Venice – or at least with the general region – and the plot was hatched to bring his physical remains back from Alexandria.

Giustiniano was delighted when the galley returned with its precious cargo intact. During the voyage, the very presence of the relics had reportedly healed one sailor from demonic possession and brought joy to all the faithful on board. The ship pulled up to the new quay that had been built at the head of the canal that was becoming the main waterway through Venice. Here, Giustiniano had been modifying the palace that accommodated the doges and the increasingly complex functions of Venetian governance. Behind the palace was an open plot of ground, a pretty if marshy space with a few fruit trees. What solid ground existed there was being supplemented by ever more tree trunks hammered into the mud of the lagoon. As Giustiniano pondered where to house the body of the Evangelist, he considered the older shrines on the outlying islands – Torcello, Castello, and Murano. But more and more of Venice’s activity was taking place on the new ground. He would build a home for the relics there, right by the Doge’s Palace.

Giustiniano had visited Constantinople five hundred years after Constantine’s transformation of the city and had seen the great Orthodox churches: Hagia Sophia as well as the Apostoleion (Church of the Holy Apostles).77 Traditionally, Catholic churches in the West were planned as “Latin” crosses, with one long arm and a shorter crossing – an arrangement that recalls the shape of Christ’s cross while providing a large space for the congregation. The “Greek” plan of the imperial churches in Constantinople was instead based on an equal-armed cross, surmounted by a dome.

Hagia Sophia has survived as a mosque, but the Apostoleion was completely destroyed in the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottoman Turks in 1453.

The doge’s concept was to bring the Greek model to Venice, where a magnificent new building would be the final resting place of the Evangelist who had been the first to translate the Gospel for a broad Roman audience. This structure would not just be a church; it would also be the chapel of the duly elected doge of Venice, adjacent to his palace, with a political as well as a religious significance. And the symbol of the city would become Saint Mark’s emblem, the lion.

Mosaic detail from St. Mark’s Basilica showing the arrival of the body of Saint Mark in Venice.

Venice: 976

The default building material in Venice was wood. Besides being plentifully available from the mainland, it was also lighter than stone and therefore easier on the city’s fragile foundation. But wooden structures were vulnerable to fire, so Venetians took elaborate precautions to prevent fires and to contain them if they started.

That night in 976, though, the fire was set deliberately. An angry crowd barricaded the portals to the Doge’s Palace and began throwing torches through the windows. The object of their rage, Doge Pietro Candiano, was locked inside with his second wife, the beautiful Lombard princess Waldrada, and their infant son. A cousin of the Holy Roman Emperor Otto I, Waldrada, as a foreigner, was only the most visible locus of Venetian dissatisfaction with Pietro. He had married her for her lavish dowry and imperial connections after packing off his first wife, a native Venetian, to the convent of San Zaccaria.

Plan of St. Mark’s Basilica.

Pietro had always been something of a renegade, rebelling against his father, who had also been elected doge, and dabbling in piracy. He was charismatic and popular in certain circles, but always controversial. He had actually been exiled to Ravenna and had to be elected doge in absentia. Arriving back in Venice in great state, he made it clear he had no patience for the city’s democratic system. He attempted to reign as a monarch, but in fairly short order the Venetians had had enough. When word came that Otto I had died, leaving Pietro without his most important ally, they attacked.

The doge’s family attempted to escape through a passage connecting the palace directly to St. Mark’s Basilica. They prayed the mob would respect this holy structure that symbolized the special relationship between the doge and the Evangelist. But when they emerged from the passageway into the church, choking in the smoke, they were surrounded by heavily armed men. Pietro pleaded for mercy, but they only laughed. The baby was quickly speared with a lance. Pietro died more slowly after being stabbed many times. In the confusion, Waldrada somehow escaped and fled the city, large parts of which were engulfed in flames.88

Chronicle of John the Deacon, cited in Norwich, A History of Venice, 42.

The message was clear. While the Venetians expected multiple doges to come from a group of prominent families, each of those doges needed to be properly elected and submit himself to the established protocols of the government. The citizens were not prepared for any doge to set himself up as king, no matter how wealthy or well connected.

When the fires were finally extinguished, the Doge’s Palace had been completely destroyed. St. Mark’s was badly damaged and its most precious relic, the body of the Evangelist, was nowhere to be found.

Efforts were made to repair the church after the great fire, and as Venice enjoyed an economic boom in the eleventh century this project grew more ambitious, culminating in a full reconstruction. While the original Greek-cross plan was retained, the new church was far more vertical, with five domes rising high above the city. The thick masonry walls required to bear their weight put a strain on the wooden supports below, but the builders persevered, convinced that the foundations would hold.

Indeed, Venetians gained confidence from their continuing good fortune. In return for the Venetian navy’s support, the Byzantine emperor Alexius I Comnenus issued a decree in 1082 that Venetian merchants could travel tax-free through the empire, and that their transactions would be free of excise taxes. This “Golden Bull” was a great advantage, and it coincided with another major economic opportunity for Venice: the Crusades.

It was a nagging humiliation to Christendom that the Holy Land had remained in Muslim hands ever since the Arab conquest of Jerusalem in 638 AD. Western monarchs mounted successive military efforts to reclaim these territories ostensibly in the name of the church, but also to enrich themselves and expand their domains. The First Crusade achieved its goal by gaining control of Jerusalem in 1099, but setbacks followed. For the next two centuries, crusaders would keep launching campaigns, with diminishing success.

Most of these expeditions flowed at least in some part through Venice, where armies purchased supplies, hired expert sailors and navigators, and sometimes even ordered entire navies. Venetian merchants had to develop a whole new system of accounting, called double-entry bookkeeping, to track these complex and lucrative transactions. Venice would also play a key role in preparing for the Third Crusade, launched in 1189 in an effort to recapture Jerusalem after it fell (again) to the great sultan Saladin. And it was in Venice that Pope Alexander III reconciled with Frederick Barbarossa, the rebellious Holy Roman Emperor who went on to lead the crusade as a demonstration of his renewed piety.

* * *

Venice: July 24, 1177

When Alexander was elected pope in 1159, his first priority was to excommunicate Frederick. The preceding pope had intended to do it but died before he could get the job done. The sentence stood for seventeen years while pontiff and emperor contended for control of Italy. The pope stubbornly maintained that he was the ultimate spiritual authority in Europe and, as such, had jurisdiction even over the emperor. Frederick, an inveterate warrior who aspired to be a new Charlemagne, supported a series of anti-popes in an effort to undermine Alexander’s position.

The result was a brutal power struggle that engulfed much of Europe in war. For a while it seemed the emperor would prevail as his armies pressed into Italy, but after a disastrous defeat at Legnano in 1176, and with an uprising against him back in Germany, Frederick agreed to accept Alexander’s terms.

Venice had managed to alienate both sides in the conflict, but Doge Sebastiano Ziani, a brilliant administrator, aimed to repair those relationships. This effort culminated in the selection of Venice as the site for the reconciliation of Alexander and Frederick. St. Mark’s Basilica was chosen as the perfect backdrop for the ceremony; although it was unfinished, the three grand portals were in place, creating a sort of triumphal arch that would frame the central figures, while the Evangelist himself would be an implied presence blessing the important event.

On a beautiful summer day at dawn, the pope arrived at the basilica and took his place on the high throne that had been constructed for him in front of the main entrance. The emperor followed. His famous red hair was going white, but he wore a brilliant cloak in his signature color, which he shed before making his final approach to the throne on his knees until, finally, he lay prostrate before Alexander, kissing his feet. The pope raised him, embraced him, and seated him on the adjoining throne.

The conflict between them had been long, bloody and personal. But in the end, the prevailing sense seems to have been relief. Later chroniclers insinuated that Alexander and Frederick had whispered insults to each other during the ritual of abasement, but contemporary records suggest this was a genuinely joyful occasion. The pontiff invoked the biblical story of the Prodigal Son, giving Frederick a fatted calf and telling him, “It is meet that we should make merry and be glad, for my son was dead, and is alive again; and was lost, and is found.”99

Norwich, A History of Venice, 114.

The two certainly seem to have been in no hurry to get away from each other, as both remained in Venice well into the fall, along with their noble and wealthy retinues. This extended visit was a welcome economic windfall for the city, as was the recognition that Venice’s unique geographic and political situation made it an appropriate location for such a delicate diplomatic mission. An eyewitness noted as much, declaring that Venice was “subject to God alone . . . a place where the courage and authority of the citizens could preserve peace between the partisans of each side and ensure that no discord or sedition, deliberate or involuntary, should arise.”1010

De Pace Veneta Relatio, as translated in Norwich, A History of Venice, 117.

Canaletto, Festa della Sensa, c. 1729–30.

While in Venice, Alexander III gave his papal blessing to a civic ritual that had more than a passing affiliation with the pagan past. Every year, on the Feast of the Ascension (the Thursday after Easter), the doge would embark from his palace in a special galley called the Bucentaur, row out into the Grand Canal, and throw a golden ring into the water, thereby symbolically marrying the sea. This Festa della Sensa underscored the special maritime nature of the city, and with Alexander’s blessing it became fully legitimate in the eyes of the church. Through the centuries, generations of splendid vessels were built for this purpose.

Doge Ziani directed the reorganization of Venice’s urban fabric as the city grew in size and beauty, concentrating on the area around St. Mark’s Basilica, which had become the undisputed heart of the city. He moved the loud and dirty shipyards to an outlying area and cleared out the space leading up from the Grand Canal to the church, making a suitable stage for civic ritual. He rebuilt the Doge’s Palace. And he continued to refine and decorate St. Mark’s.

The basic structure had been completed about a century earlier, and a program to cover the interior with mosaics had been initiated after the Evangelist’s body made a dramatic reappearance in 1094. The story went that the treasured relic had been hidden away during the fire of 976 and the three people who knew the hiding place had all died before revealing it. As the renovation work was finished, the people of Venice prayed for three days for their saint to be restored to them. At last there was a rumbling in the old masonry and the Evangelist miraculously tumbled out of a column where, the experts claimed, he had been hidden for a century.

Venetians vied with each other for the honor of ornamenting the basilica, bringing home rich treasures from successful commercial voyages. Brightly colored carved marbles, gold and gemstones poured into St. Mark’s, where they were incorporated into the ever more ornate interior or displayed in the treasury.

Craftsmen came on the ships too, most notably a whole school of mosaicists from Constantinople. This ancient art, originally created from naturally colored pebbles to decorate floors in Greece, had been widely popular in the Roman Empire and was used to adorn the first imperial Christian churches with glittering scenes of the celestial realm. The mosaics in St. Mark’s were made of small tiles, or tesseræ, which were specially manufactured pieces of glass backed by thin layers of colored material, including gold, lapis and porphyry. The result was both brilliant and durable, albeit expensive and labor-intensive to produce. The Byzantine artists who settled in Venice established a flourishing community that would survive for centuries, creating and then extensively restoring the mosaics inch by inch.

More than an acre of decorated surface coated the interior of the church, telling the long story of Christianity from the Creation and the Garden of Eden to the lives of the saints, including the miraculous translation of Saint Mark from Alexandria to Venice. Although such representations are sometimes described as the “Bibles of the illiterate,” this was not the original purpose of the mosaics. Certainly an attentive viewer who knew where to start and finish could learn a great deal from them, even if the figures high up in the domes might be obscure. But the main function of the mosaics, and the church as a whole, was to celebrate the remarkable wealth and influence that this most unlikely of cities had gained under the Evangelist’s protection.

St. Mark’s Basilica: September 8, 1202

Enrico Dandolo could no longer see the golden glow created by the bright sunshine reflecting from the water outside and bouncing off the polished surfaces of the mosaics. His vision was long gone. Two acolytes guided the elderly doge up the aisle of the basilica, but he still carried himself with authority in the distinctive headgear of his office: a white linen skullcap surmounted by a pointed hat known as the corno ducale, which made him seem even taller.

St. Mark’s Basilica was packed with the usual Venetian aristocrats, supplemented by French knights who had thronged to the city anticipating an expedition to the Holy Land. Inspired by the charismatic and energetic Pope Innocent III, the Fourth Crusade had been planned as another attempt to wrest Jerusalem away from Saladin. By the time the company got to Venice, their resources were already spent and the project seemed doomed, until Dandolo offered his support. But no one anticipated what the doge would do that day.

Interior, St. Mark’s Basilica.

Dandolo climbed into the elevated pulpit under the central dome and began speaking to the assembly. “My lords,” he said, quietly at first, “you are joined with the finest men in the world in the most noble endeavor anyone has ever undertaken. I am an old and weak man and am in need of rest – my body is failing.” There was a pause. “But I see that no one knows how to lead and command you as I, your lord, can do.” His voice grew louder: “If you are willing to consent to my taking the sign of the cross in order to protect and guide you, while my son stays here to defend this land in my place, I will go to live or die with you and the pilgrims!”1111

Geoffrey of Villehardouin, The Conquest of Constantinople, in Joinville and Villehardouin, Chronicles of the Crusades, trans. Caroline Smith (Penguin, 2008), 20.

The congregation erupted in cheers. Dandolo descended from the pulpit, weeping, and went down on his knees before the high altar, which stood over the tomb of Saint Mark. His ceremonial hat was removed and a cross was sewn onto it, where it would be easily visible.1212 A crowd of Venetians who had previously been reluctant to commit to the crusade knelt with their doge before the Evangelist. “Come with us!” the congregation shouted, as the church bells rang out.1313

Crusaders normally wore a cross on the shoulder of their cloak or tunic.

Geoffrey of Villehardouin, The Conquest of Constantinople, 20.

Enrico Dandolo had become doge in 1192 and was continuing the civic reforms of his predecessors, in which his father, Vitale, had played a major part as both counselor and diplomat. Sovereign authority was vested in the Great Council, consisting of elected representatives of the citizens. The council chose officials to serve for short periods of time advising the executive on domestic policy and overseeing diplomatic and military activities, and it appointed the committee that would elect the doge. The process for choosing a doge had evolved over centuries, and the system developed under Dandolo and codified in 1268 would remain in place until the end of the republic in 1797. It was lengthy and complex, involving ten successive votes by select groups of wellborn men over the age of thirty. The whole system appears designed to limit the power of the doge and to ensure that successful candidates had broad support among the qualified voters.1414 Venice was an oligarchy, with voting rights increasingly restricted to wealthy and noble citizens. While its government may not have been widely inclusive, it did have the virtue of concentrating power in the hands of those with the largest stake in maintaining Venice’s prosperity and independence, and they tended to be highly educated.

The doge’s powers are specifically described in Dandolo’s oath of office, which can be found translated in Thomas F. Madden, Enrico Dandolo and the Rise of Venice (Johns Hopkins, 2003), 96–98.

The Venetians’ decision to supply and bankroll the Fourth Crusade was not exclusively inspired by piety, and they demanded a say in the strategy in return. The existing plan to reach the Holy Land by first attacking the Muslims in Egypt did not really benefit the city. Dandolo was more interested in picking off trade competitors than in attacking trade partners in Alexandria, even if those partners were infidels. The Venetians observed that the passage to Egypt would be dangerous with winter approaching, and they recommended spending the cold months at Zara, a city on the Dalmatian coast that was once a client of Venice but had recently rebelled. Dandolo personally led the charge against Zara in a scarlet galley with gorgeous silk hangings, and with attendants who signaled his instructions to the other vessels on trumpets of solid silver. When they captured Zara in November 1202, it marked the first time that Catholic crusaders attacked people of their own faith, and it earned them excommunication by Pope Innocent III.

The company may not have been aware of this action by the pope when they sailed on to Constantinople. In any case, relations between Venice and the Byzantine Empire had been deteriorating since the Great Schism of 1054 formally divided the Eastern and Western churches, though the reasons were not all theological. Venetians continued to trade with Constantinople and resented incursions into their trade monopoly by rivals (particularly Genoa and Pisa). But they also resented the high-handed treatment of their merchants by the Byzantines, who viewed foreigners as greedy upstarts.

Doge Dandolo had not forgotten the unpleasantness of his diplomatic mission to Constantinople three decades earlier, nor the death of his father there on another failed mission two years afterward. He was therefore receptive to a scheme proposed by Alexius Angelus, the exiled son of the emperor Isaac II Angelus. Isaac had been deposed and blinded by his own brother, also named Alexius. The younger Alexius claimed that he should be emperor by hereditary right, and he promised to pay the crusaders generously if they threw out his uncle, Alexius III, and installed him on the throne. And so the crusaders sailed not for Jerusalem but for the capital of the Byzantine Empire, arriving at its gates in June 1203.

Constantinople: April 12, 1204

“The Queen of Cities” made an awesome sight. It was ten times the size of Venice, which had about fifty thousand inhabitants at the time, while Constantinople had half a million. Its triangular site was bounded on two sides by water, while the third was guarded by some three and a half miles of fortified masonry walls dating back to the fifth century. The city boasted hundreds of churches, huge palaces, libraries, bath complexes, race tracks and amphitheaters that had survived for hundreds of years in proud testimony to the fact that no invader had ever breached its defenses. In Rome, such things had been reduced to rubble.

The crusaders had been in the vicinity of the imperial city for nearly a year, and their patience was wearing thin. At first, things had gone according to plan because the lazy and ineffective emperor Alexius III had not adequately prepared for their arrival. Doge Dandolo led the initial charge, roaring orders from the prow of his galley and ramming the vessel aground in front of the walls, with the banner of Saint Mark streaming over him.1515

Madden, Enrico Dandolo and the Rise of Venice, 161.

Dandolo had hoped the Byzantines would rise up in support of the younger Alexius and the deed would be done with little fighting. Alexius III fled in due order, but his nephew, now Alexius IV, was greeted with apathy, and the city showed no signs of producing the hefty payment that had been promised to the crusaders. As negotiations dragged on, the Venetians grew suspicious that they had been dupes in yet another Byzantine plot.

Outside the city, skirmishes began between the Byzantines and the crusaders, or Latins as they were called. Alexius IV was deposed by one of his own nobles and thrown into prison, where he was eventually strangled. The fighting escalated until Constantinople was under siege, and finally the walls were breached.

Thousands of enraged (and starving) crusaders rampaged through the city, which was quickly engulfed in flames thanks to the ceramic vessels of “Greek fire” that were delivered from the Venetian ships by catapult. This highly incendiary substance had once been a Byzantine secret, but now it was turned against the empire. The Byzantines who were not cut down started to flee in large numbers as the Latins divided their time between rape, plunder and devastation. At Hagia Sophia, a prostitute was seated in the high chair of the Orthodox patriarch, where she sang a dirty song and drank wine out of a communion goblet. Anything of value disappeared into the flames, the official inventory of plunder, or the pockets of individual crusaders.

Tintoretto, The Conquest of Constantinople in 1204, 1584.

After three days, some semblance of order returned, although the city was almost unrecognizable – a burned-out shell with a shadow of its former population. The leaders of the crusade began divvying up the spoils, with Venice receiving three-quarters of the booty by prior agreement. This massive haul justified Dandolo’s support for the expedition from the Venetian perspective, even as the rest of the Latin West was shocked at the ravaging of Constantinople by fellow Christians.

Within weeks, the crusaders had chosen one of their own, Baldwin IX, Count of Flanders and Hainaut, to become Emperor Baldwin I.1616 It was rumored that Dandolo turned down the crown, and he seemed less concerned with ceremony than with governmental affairs and selecting objects to send back to Venice, particularly the four bronze horses. The doge died in May 1205 of a septic hernia sustained during a three-day ride visiting his troops outside the city, and was buried in Hagia Sophia – the only man to be so honored.

The “Latin Empire” in the East would last only until 1261, when the Byzantines once again gained control of Constantinople.

St. Mark’s Basilica: February 1438

The Byzantine courtiers could not help but be impressed. They had traveled west seeking aid, and Venice was putting on a fine display of its wealth. More than two centuries had passed since the crusader sack of Constantinople, which still bore physical scars from the attack, but an even more brutal enemy was now at the gates. The Ottoman Turks had already whittled the empire down to little more than the capital city itself, and the emperor could not pick and choose his friends. John VIII Palaeologus had come personally to seek reconciliation with the West, hoping it would bring material assistance from Christian allies to keep Constantinople out of Ottoman hands. Along with the leaders of the Orthodox Church, he would be attending an ecumenical council in Ferrara (later transferred to Florence).

Pisanello, medal of John VIII on his visit to Italy, c. 1440.

The Orthodox patriarch of Constantinople, Joseph II, had expressed a special interest in visiting St. Mark’s Basilica. He arrived in state at the quay beside the Doge’s Palace, and the long retinue of courtiers paraded down the Piazzetta toward the basilica, pausing frequently to examine objects of interest. While relatively small in comparison with the colossal churches of the imperial city, St. Mark’s made up for it in opulence. The mosaics were largely complete by this point, and the spoils from the Fourth Crusade had been carefully installed throughout the complex. Sophisticated visitors like the Byzantines would have understood the messages conveyed by the sumptuous decoration.

For example, there was the statue of the Tetrarchs at the corner where the church met the passage to the Doge’s Palace. The Tetrarchs had been created to represent the four rulers of the Roman Empire when it was administratively divided for a time before Constantine gained sole control. Made of the dense purple stone called porphyry, which in Roman antiquity was exclusive to the emperor, the statue had stood for more than eight hundred years at the Philadelphion, the great council hall of Constantinople, as a symbol of unity and good governance. Now the figures were embedded into the juncture of church and state in Venice, which claimed to have extended its influence into the four quadrants of the old Roman Empire.

The courtiers gazed at them dejectedly, and even more so at the gilded horses prancing over the central portal of the church. Like the Tetrarchs, this foursome had become symbolic of Venice’s power, but the horses had an additional and more ancient significance. The details of their creation were obscure, but the prevailing impression was that they had originally come from Greece. Fantastic rumors said they were created by Phidias for Pericles, or by Alexander the Great’s favorite sculptor, Lysippus, as the quadriga, or four-horse team drawing the chariot of the sun. While neither attractive attribution could be proved, the horses were undeniably of the highest quality.

The Tetrarchs, c. 300 AD.

When the horses first arrived in Venice, they were stored for a time at the fortress known as the Arsenale. Representatives of Florence, whose rising republic was beginning to rival Venice, circulated a spiteful story that they were saved from being melted down only by the intervention of some Florentines who truly understood art (although it would have been easier to do the melting in Constantinople had that indeed been the intent). But even if the Venetians had been incapable of recognizing the horses as great works of art, their connection with the revered Enrico Dandolo would have protected them.

In any event, their period in storage was brief. By 1267 they had been hoisted up over the main entrance to St. Mark’s onto a marble platform where the doge customarily addressed the Venetian people after his election. From here on out, he would deliver his oration flanked by a pair of horses. But they were not there solely as an accessory for the doge, although they remained closely linked with the office.

According to Saint Jerome, the four Evangelists – Matthew, Mark, Luke and John – were the quadriga of Christ, who drew his light into the world through the Gospel.1717 So while the mosaics on the lower walls of the church focused on the story of Mark and his miraculous transfer to Venice, here at the base of the dome he took his place as one of a sacred foursome that transcended the earthly realm. It would not have escaped the notice of the visiting Byzantines that the position of the horses over the five entrances to St. Mark’s also echoed the traditional arrangement of a Roman triumphal arch, thus not only filling a sacred function but also commemorating in perpetuity the Venetian-led capture of Constantinople.

Freeman, The Horses of St. Mark’s, 100.

Detail of the façade of St. Mark’s Basilica.

The Byzantine retinue moved on into the church and were shepherded up to the main altar. While many churches had large, elaborate altarpieces, the one in St. Mark’s was unique: it was solid gold, glimmering in the light of the hundreds of candles that had been lit for these special visitors. (The winter weather had been miserable, depriving them of the famous reflecting sunlight of Venice.)1818 The doge led the way into the apse so they could walk all the way around the altar, known as the Pala d’Oro (or Golden Altar), and see the brilliant gems and exquisite enamels embedded in the gold. The main dignitaries then gathered symbolically under the great central dome for a staged display of unity, while a smaller group of courtiers lingered by the Pala d’Oro to examine it more closely.

The Memoirs of Sylvester Syropoulos IV.21, available at the Syropoulos Project, www.syropoulos.co.uk.

“It is something of a hybrid,” one of the Venetians explained. “The main body was made for us in your city many years ago, with the story of Saint Mark across the bottom. Then the top part, with the icons, came after the Latins took Constantinople.” He paused awkwardly before adding, “It was all legal, of course, as captured enemy property.”

Pala d’Oro, 976 and 1342–45.

Detail of the Pala d’Oro with Empress Irene.

“We understand these things,” replied George of Trebizond, a classical philosopher who was a close aide to the emperor. “But how did they become a single object?”

“Andrea Dandolo – descendant of our great doge Enrico Dandolo – was the procurator of this church before his own election as doge, and he is responsible for much of what you see here. It was his idea to unite the old and the new, and make the most beautiful altar in Christendom. There are thousands of jewels and pearls – so many that it is impossible to count them all. The enamels came from your own Hagia Sophia – and as you know, Doge Enrico has the honor of being the only man buried there.”

The Byzantine philosopher was quiet for a moment, and then he remarked, “Is it not curious, my friend, how the sight of these beautiful things fills you with pride and delectation, while for us they are objects of sorrow and dejection?” As the Venetians nodded sympathetically, he continued: “But are you certain the panels came from Hagia Sophia? What do you think, Sylvester?”

One of his companions, Sylvester Syropoulos, happened to be a high official at Hagia Sophia. “According to my reading,” he replied, “they are actually from the Pantocrator monastery. There can be no doubt – the inscription around the image of Empress Irene, who was a great patroness of the monastery, proves it.” His satisfaction was obvious. “This is undisputedly a glorious and most artful object, but imagine how much more impressive it would be if the panels had indeed come from the great church!”1919

The Memoirs of Sylvester Syropoulos IV.25.