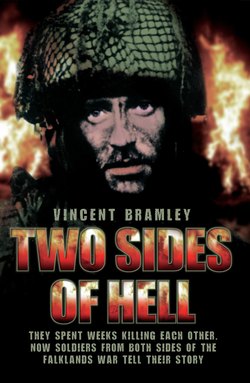

Читать книгу Two Sides of Hell - They Spent Weeks Killing Each Other, Now Soldiers From Both Sides of The Falklands War Tell Their Story - Vince Bramley - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеTHIS BOOK began life between April and June 1982, when I and thousands of other ordinary soldiers, British and Argentinian, met on the battlefields of the Falkland Islands. War is something we British have been used to for centuries. By contrast, Argentina is a relatively young nation and in its much shorter history it has fought few wars, suffering more from internal conflict than external.

The Falklands war, by comparison with the two world wars and many much smaller conflicts, was a small-scale affair, but it was a war nevertheless. What is significant is that it was an undeclared war, the politicians preferring to use the word ‘campaign’. Calling it this does not alter the fact that hundreds of soldiers lost their lives and hundreds were wounded. And, as at the end of most much larger wars, a political regime collapsed – the military junta of General Galtieri.

Some years ago I asked myself who the real winners of the war were. Was it the Falkland Islanders? They have their freedom again, but their life is hardly the same as it was before 1982. Or was it the British government? The Conservative Party undoubtedly won a second term in power largely through Britain’s military success, after which a wave of patriotism and a renewed sense of national unity temporarily swept aside the country’s economic troubles.

Or were the victorious soldiers the winners? The soldier receives a medal and returns, often with difficulty, to peacetime life. He also has the sense of having done the job he is paid to do: to fight. But I believe that, in addition, he has the knowledge that he has served democracy, and in my view it is justified to fight in its defence as we did. Therefore it is ironic that, during a war waged against the suppression of democratic freedoms, those freedoms should be abused at home. The Falklands war was a heavily censored war – and a war that was heavily stage-managed through the media. Not only did faceless bureaucrats in the Ministry of Defence (MoD) monitor very carefully the British press coverage, but, as I noticed as soon as I returned home, the war was publicized in such a way as to appear completely clear-cut.

At the time I could easily imagine the ordinary man or woman thinking: ah well, this business down in the Falklands doesn’t seem to have been too bad. And yet, with the perspective of time, it seems that the public weren’t totally hoodwinked by MoD censorship. For they donated millions of pounds to the relatives of the dead and injured. And that is what makes me feel proud to be IBritish. For me, winning the war is secondary to that feeling.

But while the public cared, the government clearly did not, as is evident from the stories of some of the soldiers interviewed for this book. The nearest the ordinary citizen can hope to get to knowing the truth is to be related to a soldier who served in the Falklands, or perhaps even over a pint in a pub, with a veteran who chooses to reveal what the MoD wished to conceal.

For a number of years now I have studied military history, and this interest brings me to the question of who writes the history of our wars. Usually it is either a professional historian, a politician, a journalist cashing in as soon as possible after a conflict, or a general writing his memoirs, in which he explains how he won the war. They will not have been in the thick of the battle. But if any of them has, by all means let him tell you the facts.

The result of this ‘expertise’ is that the reader is left not much wiser about what soldiers are like or what actually happens in battle. The book you are about to read will, I hope, dispel some of this mystery, and present more than a few hard facts. The public lack of understanding of soldiering is something I see even more clearly now that I am back in civilian life. I am not saying that all the blame lies on the public’s side, for as often as not when a civilian meets a career soldier there is mutual misunderstanding.

We have looked at how history is presented to us, and that is one of the main reasons for public ignorance of military matters. But the soldier himself is steeped in a culture that blinkers him to life outside the forces. He will talk with a sparkle in his eyes of the comradeship and deep friendship he finds in the Army, and of the structure the regiment gives to everything he does. A soldier fights not for Queen and country but for those friends he loves and respects, and secondly for himself.

By this time the civilian is thinking to himself that this guy must be from Mars, or that he has been totally brainwashed. I can tell you that brainwashed he is not. What is talking is comradeship and a sense of discipline that is instilled in him from the day he becomes a soldier. Now, discipline is something that both sides should agree on, given its ever-faster erosion by a tide of crime and lack of respect for person and property.

What form does military discipline take and what are its results? The British Army is famous throughout the world for its discipline. The civilian knows that much, but what is less well known is that an important element that sustains it is elitismelitism. Not the elitismelitism of the officer class, but the pride that regiments take in their own superiority. Each member of a body of fighting men is disciplined to preserve that sense of superiority – not, of course just to brag about it, but to demonstrate it by actions within the commonly agreed code of conduct.

One of the great strengths of the Army is its cap-badge rivalry, its inter-unit competition. In the Parachute Regiment we refer to other regiments as ‘craphats’. The Royal Marines, although part of the Royal Navy, are also craphats, or ‘cabbageheads’, both names coming from the colour of their headgear. In general, anyone not in a red beret is a ‘hat’. Senior officers at the MoD are ‘heavy hats’.

It is rivalry – nothing more, nothing less. Other units have names for us which I couldn’t possibly dignify by repeating here. However, I believe, like many of my comrades, that far too much emphasis was placed on cap-badge rivalry during the Falklands war. The blame for that lies firmly in the lap of certain senior figures who should have known better. As one of my former comrades says: ‘There are good hats. And there are very brave hats. The Parachute Regiment would not exist or be capable of carrying out all its tasks if it was not for the hats in support.’

In fact the main obstacle in the path of today’s Parachute Regiment is senior members of the Army and the Ministry of Defence. They have never liked the elitism of units like the Paras, particularly in peacetime, and this attack on constructive rivalry affects many parts of the military machine. But when a war breaks out the faceless officials of the MoD suddenly start begging for military success and they want elitism without delay if it means securing their own jobs.

In the present, probably short, period of peace these same mandarins are striking in another way at the very heart of professional fighting units like the Parachute Regiment. They have dreamed up a redundancy programme under which excellent soldiers are leaving a dwindling band of their comrades to fight a welter of red tape. The result is that the morale of those in the ranks is being sapped. But it is more serious still when we remember that it were not many decades ago that a British prime minister stepped off a plane bearing a piece of paper and spoke of ‘peace in our time’. The sad thing is that those officials in grey suits argue more passionately about the removal of a tea and coffee machine from the corridors of the MoD than about the disappearance of yet another superbly trained body of fighting men.

In 1991 my first book, Excursion to Hell, was published. It was my own personal perspective on the Falklands war, and in particular the battle for Mount Longdon. My aim was to give the view of the ordinary soldier, but the government did not want to know the facts of warfare as I and others like me saw it. It was not the sort of book a senior military commander would have written, one that would have been thoroughly vetted by the Ministry of Defence. But the fact is, it did not escape official attention, for fifteen months after its publication they initiated a police inquiry conducted by Scotland Yard.

I could write a whole book on this painful episode, but what stands out is the tacky way the government handled the affair. The unmistakable message was that only they can call the shots in such matters. However, I believe firmly that the ordinary soldier has the right, just like a general or a politician, to publish his account of that, or any other, war. I object to bureaucrats distorting the facts, contradicting the experience of those who were there.

Military writers often glorify war. This book is not about glory. It is simply about individuals thrown together in war. My aim has been to write it in such a way that its message is clear to every reader, from the high-ranking civil servant to the ordinary man who has no understanding of military matters. Nor is this book an apolitical study. I ask you to put aside your opinions about the political rights and wrongs of the Falklands and read it as an account, largely in their own words, of soldiers of both sides who fought in that war. It is about their lives before, during and after the Falklands: how they came to find themselves on those bleak islands, what they experienced in battle and what happened to them and their families afterwards.

In June 1993 I travelled to the Argentinian capital, Buenos Aires, for the first time, in the company of two ex-members of the 3rd Battalion, Parachute Regiment, and representatives of the newspaper Today. There, in a backstreet hotel, we met on camera two Argentinian veterans of Mount Longdon. The aim of our visit was to show that the soldiers of two formerly warring nations could meet amicably without governmental interference or prompting. It took place at a sensitive time, for an inquiry into alleged war crimes by British soldiers was currently in progress.

It was while talking with my interpreter that I glimpsed the possibility of a book based on frank discussions between myself and both Argentinian and British Falklands veterans. The unstinting help of Patricia Sarano, of the Argentinian television company Channel 11, was to prove invaluable. I gave her a list of questions for other Longdon veterans. These men she tracked down and interviewed informally, faxing the transcripts to me back in England. Three months later the synopsis of this book was approved by the publisher.

It was now that my real work began. My research clearly had to extend beyond talking to four or five ex-soldiers. To make things more difficult, as a result of the police inquiry my name was being splashed across the national newspapers every few weeks, so that it became harder to get Paras I had fought alongside to come forward.

Nevertheless, between October and December 1993 I interviewed five ex-members of 3 Para at great length, noting down every relevant detail of their personal lives. And I spent hours each day pinpointing their exact movements during the battle for Longdon. Over Christmas, after long, hard negotiations with friends in the know, I persuaded a twenty-four-year-old Argentinian living in England to assist me in my research in Argentina. Meetings took place in locations chosen to ensure confidentiality, primarily to prevent either the British or the Argentinian press from getting wind of the planned second trip. This may all sound overdramatic, but during that period certain members of the press were taking every step to probe into my life and hinder me. It is something I shall not forgive. To hell with them!

I first met Diego Kovadloff through a brief interview I gave to an Argentinian magazine. His impeccable English, his intelligence and his sense of humour forged a friendship between us at once. This young man, fourteen at the time of the Falklands war, was to become a vital link in the chain of production of this book, as his interpreting skills were essential to me. After numerous telephone calls to Argentina we had gained the agreement of a number of Longdon vets to meet us in their own homes.

On 18 January 1994, after flying via Switzerland and Brazil, we arrived in Buenos Aires to complete my research. I was nervous as I stepped off the plane and I was acutely aware that, knowing no Spanish, I had to rely totally on Diego for what would be a very emotional exchange for both sides. Also, I knew that if just one reporter knew I was there, not only would six months’ work be destroyed, but our Argentinians would be unlikely to assist me. This was all the more probable because they are understandably reserved as far as the Falklands war is concerned.

How would I react to meeting the soldiers who had played a part in killing my friends? On the other hand, how would they feel seeing their former enemy? Would they focus on the politics of the war? Would they embroider the truth, or just downright lie? A thousand questions raced through my mind as we drove to a secret address in the Argentinian capital. After all, as far as I know, no one has written a book like this, where the author fought the very people he later interviews.

Buenos Aires has a strong European feel to it, inevitably mainly Spanish although the influence of Italy and Britain is also marked, particularly in the architecture. Cafés and newspaper kiosks lining every main street also gave it a continental European character. But what struck me immediately was the way the people drive. Where possible, they race at high speed along roads with few road signs and then bunch up like racing drivers at the lights, with perhaps eight cars straddling a road meant for four or five.

Impatient drivers revving up and sounding their horns at the lights are not unheard of in Britain, but they are more like the norm in Buenos Aires. In the suburbs the lights are often ignored completely, and driving along those roads I felt like I was at the wheel of a dodgem car at a fairground. The state of repair of the roads hardly makes for a smooth ride either. After experiencing this and the frantic driving of the locals, I’ve not complained about our roads once since being back in England.

On the whole I found the people of Buenos Aires honest and polite, and the service in restaurants and cafés prompt and friendly. I was learning about a race of people I had been conditioned to think of as overexcitable and quick-tempered. Our cultures are undeniably different in many ways, but I soon felt relaxed in this lively, round-the-clock city.

However, in the suburbs of Buenos Aires I saw the stark poverty in which very many of the city’s populace live. They do not have the safety-net of unemployment benefit like Britain’s, and receive next to nothing from the state. It was a common sight to see street vendors as young as six standing on street corners or threading their way between cars waiting at traffic lights. The poverty I saw made me realize how, relatively speaking, everyone is materially comfortable in Britain. We have deprivation in our inner cities, but nothing to compare with what I saw.

Most of the people living in the suburbs, where I was to interview the Longdon veterans, live in single-storey bungalows consisting of a living room and kitchen in one, one or two bedrooms and a bathroom. They are small compared with the average two-storey terraced house in Britain. Normally a large table dominates the living room, where there is usually also a TV. The occupants sit and talk for hours around this table in a time-honoured tradition of family life.

The Argentinians pride themselves on eating well, particularly steak and barbecued food. After coffee it is the normal practice to sip a tea called maté from a pot with a spout. It reminded me of the American Indians passing round the peace pipe. The first time I was offered maté I thought it was a drug in liquid form, like hash oil. Nevertheless I liked it.

The Argentinians I was to interview all lived in Lanus or Bandfield, twenty minutes’ drive from the centre of Buenos Aires. They had belonged to the 7th Mechanized Regiment, an infantry unit, and had been conscripted from the same area, unlike the British Army, in which men from all over the country serve together. We have a voluntary army with a professional structure, whereas the Argentinians operate a system of conscription.

At birth every Argentinian citizen is given a national identity document which has to be renewed when the holder reaches sixteen. For males this renewal entails inclusion in a ‘class’ based on year of birth. In May of each year a conscription lottery is broadcast on the television and radio and printed in the newspapers. The numbers published refer to males who have reached the age of nineteen: it was mainly Class of 62 that served in the Falklands war. Young men whose last three digits on their identity documents correspond with the lottery numbers must present themselves for a medical examination in their local military district. Since a percentage will be exempted from service on medical grounds, more men than are needed are called up.

This sounds complicated to us who have a voluntary system, but it works. A further feature is that, by law, all conscripts working at the time of their call-up have their jobs left open for them and 75 per cent of their wage is payable during military service.

Because Argentina has not experienced war on our level, it has no firmly established aftermath programme for its soldiers. The government failed to respond adequately to the needs of those suffering physical and mental injury as a result of the Falklands war. Despite the difference between our countries, this will strike a familiar chord in many British veterans of the campaign.

The Argentinians do have veterans’ groups, although over the past twelve years the movement has become split. Some groups regard their position as largely a political issue, and make their views felt, while others aim to quietly rehabilitate one another in group discussions. I am well aware that some Argentinian veterans wouldn’t dream of sitting down to talk with me, an Englishman. That is why I had to secure the interviews before leaving Britain.

For fourteen consecutive days after our arrival in Buenos Aires, often working sixteen or eighteen hours a day, Diego and I interviewed my former enemy. With each individual I met I was unsure of how I would be received. But what I witnessed in every home has changed my outlook completely. As one soldier to another, we acknowledged our shared experiences, and each man wanted the public to know his story – just like my comrades from 3 Para. I was greeted in every home I went to with a sincere handshake, a hug and, most moving of all, a friendly smile. Not once did I come across suspicion or even lack of courtesy.

Food was always provided, along with beer to smooth the proceedings. Other members of the family sat in on most of the meetings, in many cases hearing their relative’s war experiences for the first time. They were all eager to learn about the British way of life, my friends and our military system. One of the veterans said to me: ‘This is a weird experience. Never did I think an English former enemy would come here into my neighbourhood and my home, but the funny thing is, it’s going to be an Englishman that’s going to tell our story! Nobody has really bothered to listen to us. Because we lost, everyone ignores us. After all, I did have many friends killed. It still hurts today.’

After meeting men like this, and feeling their genuine warmth alongside the sadness of their memories, I realized that every veteran I spoke to would, regardless of the language barrier, fit in socially in a British pub on a Saturday night. And for me that was an important discovery.

I must now thank all the people who have supported and helped me over the two years it has taken to research and write this book. Without Patricia Sarano’s contribution you would not be reading this book today. The same goes for Diego Kovadloff, whose excellent interpretation and translation, support and humour have been of immeasurable value. I would like to thank Jorge Altieri, who worked tirelessly to establish contact with his former colleagues for me, and Edgardo Esteban, who assisted with professional confidentiality in the case of further contacts. Thanks to the Argentinian family who accommodated me while I was researching in their country. They have asked to remain anonymous. Thanks also to Chuchu and Juan, two civilians who wined and dined me at all hours during my brief periods of free time.

Many thanks to Julie Adams and Steve Tebbutt. (Thanks for the photocopier.) To all the staff at Bloomsbury, particularly David Reynolds and Nigel Newton, who had faith in this project. To Richard Dawes, whose professional help and advice over the years has made him a valued friend. And special thanks to Alastair McQueen, who as my editor navigated his way through my manuscript and who has guided me away from the press harassment which has been an unpleasant feature of my life for nearly two years.

I want to thank my friends who have stuck by me during this most difficult period, in particular Paul Read and Martyn Benson. Also my parents, Fred and Pam, my brother Russell and my Uncle Brian, whose support for me throughout my life has never wavered. And particularly warm thanks to my wife, Karon, who has suffered long and hard with me. She and all my family have proved pillars of strength.

I offer this book to the memory of all who lost their lives in the Falklands, British and Argentinian alike. They cannot tell their story.

AT THE GOING DOWN OF THE SUN AND IN THE MORNING

WE WILL REMEMBER THEM

Vincent Bramley

Aldershot, July 1994