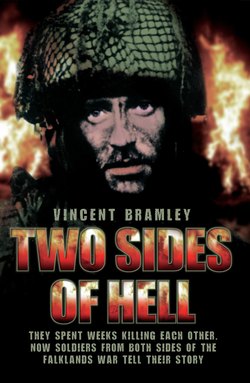

Читать книгу Two Sides of Hell - They Spent Weeks Killing Each Other, Now Soldiers From Both Sides of The Falklands War Tell Their Story - Vince Bramley - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1

ОглавлениеSANTIAGO GAUTO drew deeply on his cigarette, making the red end glare fiercely. He held the smoke, then blew it up towards the ceiling. For a moment he paused, then he began to relax, and I was glad I had come here to this modest little house near Buenos Aires to meet a man my comrades and I had been trying to kill almost twelve years before.

He had greeted me at the door with a welcoming smile and a friendly handshake, then showed Diego, my interpreter, and me into his kitchen cum living-room. We sat round the table and he looked me in the eye and said: ‘This is my home, Vincent. It is yours, too. Please.’ Then he passed me a cool beer from the fridge, saying: ‘Let’s have a beer together. It’s an honour to meet one of my former enemies.’

‘Salud!’ We raised our bottles of beer and I handed him an English cigarette and together we smoked and drank our beer and began to talk. We had both been a little nervous and, deep down, wary about this meeting. But now the ice was broken, we had overcome the first hurdle, and the chat was flowing, particularly about why I had come to see him. We were both as curious about each other as any soldiers from opposite sides when they meet so long after a battle.

For a moment that great smile flashed again and then he said seriously: ‘It is a brave thing you do, brave of you to come here alone, so far, to be surrounded by people who – even though it is all a long time ago now – could still want to harm you because you are English. I appreciate what you have done, what you are doing. Believe me, it is a brave thing and a big thing you do here today. I am proud of being chosen by you, Vincent. Maybe it is one of those beautiful chances in life… Someone picked me out, gave you my name and now we meet. Yes, it is brave, brave for both of us to meet.’

Watching me with deep, dark, puzzled eyes from behind the curtain which served as a door was Mayra, a classic picture of beauty and childhood innocence, bewildered by the strangers and the language they spoke to her father.

Sensing her confusion, Santiago said: ‘Mayra, come to Papa.’

Diego talked quietly and calmly to his seven-year-old daughter and I turned to watch his lips as he translated the conversation. ‘Don’t be afraid, Mayra,’ he said. ‘This man Vincent has come from another country, a country many miles away. Many years ago, before you were born, he and I were enemies. We tried to kill each other for what we both believed was right. Don’t worry – now we are at peace. Now we are about to become good friends.’

I looked at Diego as I stubbed out another cigarette. His eyes had filled with tears. I turned to the little girl as she moved from her father, came towards me and climbed on to my lap. She, too, was crying, tears rolling down her little face. Then she kissed me on the cheek and hugged me.

‘Papa respects you. We are all friends now, yes?’

‘Yes,’ I said, wiping her tears away in just the same way as I do for my own daughters when they are afraid or upset.

The room was quiet for a while, all of us deep in our own thoughts: me, the intelligent, big-hearted hospitable man who was my enemy, and Diego, who was too young to have had to endure the craziness of those events on the Falkland Islands so long ago, which to those who were there seem like just last week or even yesterday. This man, who was once my enemy, showers me with the hospitality and respect unique to soldiers who have fought each other, who have given of their all and who now accept that the war is over and that we should be friends.

He stubbed out the English cigarette and said: ‘Good fags, Vince.’ And the silence was broken. ‘You know, I started smoking when I was fourteen and I still can’t make my mind up whether it’s a habit or for company!’

We laughed and his eyes swept the room. ‘I was born here, on a table in this very room at four o’clock in the afternoon on 4 May 1962, the youngest of a family of four brothers and a sister. The woman who delivered me was called the local midwife, but she wasn’t really a midwife, just a tough old woman from the neighbourhood. Unlike a lot of people my parents are true Argentinian. My mother’s father was a chief from the Guarani tribe from Corrientes, a province in the north-east of the country. When I was four or five he came to visit, to see me, his latest grandson. He had a big gaucho knife in his waistband, but he refused to sleep in the house. He slept outside because he thought the roof might fall in on his head. He was from a different culture, as were my parents, and times were different then. Hard times. But when you see what is happening in the world today it makes you wonder if things weren’t better then.

‘When I was five my parents split up and my mother was left with the five of us. It was hard for her, on her own having to fend for us, but we survived. You have to, don’t you? My childhood was tough, but I have no complaints. It was tough for all the other kids in this area. Under the circumstances I was happy. I wasn’t brilliant at school, but I passed through primary school and then left in the third year of secondary school. I was at school with Beto – Jorge Altieri – another veteran of the Mount Longdon battle. We knew each other because we lived in the same neighbourhood.

‘I got a job in a printer’s and was soon earning more money than my mother, even though she was working in three houses, looking after a couple of blind kids in one place, cleaning another and caring for an old lady in the third. My sister left home and one of my brothers got married. Another went off to the south of the country to work as a mechanic. I was able to save some money by this time. Every weekend I would go to the discos in my best clothes. I loved boots: Texan-style cowboy boots. I remember buying my first pair, the unforgettable feeling of getting something you had saved for.’

Just before his nineteenth birthday Santiago received his summons to do national service and thus had his first experience of the chaos and confusion which reigned in the Argentinian Army at the time.

‘There were too many of us. I, along with four others, was surplus to requirements, so they put us on a plane and sent us to Puerto Deseado, Santa Cruz, in the south. They didn’t want us either so within seven hours we were back on a plane to La Plata to report to the 7th Regiment, which was my district regiment anyway.’

He was sent for induction training in San Miguel del Monte and it was his tough upbringing which saw him through, particularly the ‘dancing’, or what is called ‘beasting’ in the British Army.

‘In San Miguel the instructors told us it would rain every day, but it didn’t and they were really disappointed that the weather held until the very last day. We learned basic soldiering, marching, saluting, fieldcraft and, of course, we had ‘dancing’ – everywhere, every time, dancing. I became good friends with a guy called Dario. We became solid mates; the sort of friendship you make in rough times.

‘At one time Dario was laid up for twenty-five days in a tent very ill with a swollen testicle. He couldn’t move and he wasn’t able to walk to the cookhouse for his food. I said I would take food to him. The corporal made me dance all the way every time, making me crawl; run, anything, all the time screaming in my ear: ‘Come on, you fucking faggot, take the food.’ It was exhausting, I was flat out, and they kept dancing me just because I wanted to take food to a mate.

‘Another day I was being danced by a corporal for no reason at all when an officer asked him why. He said it was because I had been rude. The officer asked for witnesses and the whole company backed me up. The corporal spent fifteen days under arrest. At least one of our officers had a sense of decency. He went by the book, yeah?’

At the end of their first forty-five days of initial training. Santiago was one of a small group regarded as the best in the intake. He was rewarded with five days’ leave. So, too, was his pal Dario Gonzales, who, despite his injuries, had made the grade. Santiago was sent as a batman to a lieutenant, and Dario to a captain. For a while it was relaxing, sometimes playing chess with the officers and occasionally beating them at it.

Santiago was intrigued to discover that almost every man in the company had the same blood group. Was that the way they decided on a military formation? He supposed it made things simpler for the medics if everybody was the same should they go to war.

Thirty of them were selected to form a commando group within the company. Extra training followed and the days of chess with the officers were over.

‘We had instruction at night in all weathers. It was fucking freezing in winter. We were taught how to make and plant booby-traps, we did lots of extra shooting and had to strip and assemble weapons while blindfold. They even taught us how to stop an electric train, which was fuck-all use to us. Maybe one day I’ll go to the station and stop one!

‘I was still looking after my officer. He was a collector of weapons and I used to have to go to his home to clean his guns. I’ll always remember he had a beautiful original Luger. We also had to do a lot of training for a running competition which we won and they gave us medals.

‘One time Brigadier General Joffre, who commanded X Brigade and was also Land Forces Commander in the Malvinas, came to visit us and see something at the nearby theatre. All thirty of us were ordered to escort him and guard him. We all lost our leave to look after him. Arseholes.

‘On the whole, though, I had a good time. We were a good group with a good attitude and we behaved ourselves and got on with it. We got more leave than the rest and because of our behaviour I got an early discharge. I was out on 23 December, in time for Christmas, and on the way home I was the happiest man around.’

Santiago did what many young men then liked to do as soon as they got away from the clutches of authority. He grew his hair. He was back in his old job at the printworks and happy. He had done what his country demanded of him.

But four months later he was back in the barber’s chair on an Army base, his treasured locks on the floor, his tooled cowboy boots replaced by Army-issue ones. Santiago had been recalled and was back in the 7th Regiment. No matter what the future held, his mother, at least, would be OK. Under the law his employers were obliged to pay his wages to her while he was called up. (It was only when he returned from the war that he discovered they hadn’t sent her a solitary peso.)

‘We left for El Palomar for a flight to the Malvinas. The streets along the way were full of people waving and cheering. It was all very patriotic. Some guys got carried away with it all. But some other guys were thinking other things. I remember asking myself: Where the fuck are we going? What for?’

I met Jorge Altieri on my first visit to Argentina, in June 1993, eleven years after the Falklands. I had gone there with Denzil Connick and Dominic Gray, two of my comrades from 3 Para, and Alastair McQueen of the London newspaper Today, who had covered the Falklands war for the Daily Mirror, and Ken Lennox, another Mirror veteran who was now the chief photographer on Today. The Today team was with us to cover the first meeting of veterans of the battle for Mount Longdon. That was all we had gone to do: to meet, shake hands, and talk to each other of our experiences.

However, after meeting Jorge and another veteran, ex-Corporal Oscar Carrizo, everything changed. The meetings with these guys laid the foundation for this book. I only spoke to them for a short time through Patricia Surano and Daniel Fresco, two researchers for Argentina’s Channel 11 television network. The information from these brief, off-camera chats hit me like a thunderbolt. These men had stories to tell. Their war, too, was a terrible one.

I left Patricia a list of questions and she tracked down four more veterans and sent me their answers and a taste of their experiences. The more Patricia dug, the more enthralled I became and it was on her research that I based the original synopsis for this book.

Six months later I was on the streets of Lanus, just outside Buenos Aires, with Diego at the height of the rush hour to meet Jorge, this time away from the cameras and the reporters with their prying questions. He had worked tirelessly contacting other veterans of Longdon, and now he greeted me like a long-lost friend and led us through a maze of backstreets to his home for a meal with his wife and parents.

In many ways Jorge’s home is a shrine, a living memorial to his days as a soldier. The blue and white flag of Argentina stands proudly against a wall. There are certificates, souvenirs and replica weapons hanging on the walls. Grapevines form a canopy over the table in the backyard.

After the meal the others watched and listened quietly as Jorge and I pored over photographs and maps of Mount Longdon, pinpointing our respective positions on that fateful day in June 1982. Jorge’s polite manner to me, his former enemy, put me at ease and we both relaxed completely as the evening wore on. From time to time he would smile warmly at me across the table and as he told me his life story in his soft voice I couldn’t help thinking of this man as a friend. At the same time I felt great sympathy for him because his account of the war itself reminded me of the stories of some of my own comrades.

The son of an Italian immigrant mother, Jorge told me: ‘These streets round here, these streets of the Monte Chingolo Estate, are my streets. These are the streets where I grew up, where I played. My mother was married before, to a policeman who was killed in the line of duty. When she marred my father she had two sons, my brothers. I have good, loving parents and brothers.

‘Like thousands of other kids from this area I went through primary school, but dropped out of secondary school after my first year. I just wasn’t interested. I did a short course at technical school studying radio and TV. My real love in life was martial arts. I discovered the joys of the techniques when I was fifteen or sixteen. My brother, Miguel, and I went to see all the Bruce Lee films. They just fascinated me. I was in a club, the Bandfield Club, and practised judo three times a week for two hours. Lots of other kids came to try it out, but they gave up. I stuck with it and then Chan Do Kwan, another martial art, which I did on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays. In the end I was in the gym training six days a week. I won a judo competition at the Universidad de Belgrano. I was a blue belt at Chan Do Kwan and orange-belt standard at judo as well as being secretary of the judo club. I loved it. I was about to start a job as an instructor in self-defence for the police in our area, but then my number was called and I had to go to do my duty as a conscript.

‘I could have got out of it because I was born with a nasal problem and I could have proved to them that it had left me with a breathing difficulty, but I wanted to go in. I even fancied my chances of becoming a regular and maybe even ending up a corporal or sergeant.

‘I remember we all gathered to be taken to the 7th Regiment camp, expecting to go on trucks, but they made us walk. And when we got there they told us: “You’re conscript soldiers. You left your balls outside. Inside, we command everything, so don’t play the cock here.’

‘They gave us all green fatigues and our civvies went into a locker. I knew not to take good clothes – I went in old ones. If you take your best clothes they get nicked. Then they divided us up by height and sent us to different companies. I was sent to B Company.

‘My name, Altieri, caused me problems straight away. A corporal called Rios thought I was a relative of General Galtieri. He just wouldn’t have it that my name was different. So because of my name I got my first dancing lesson.

‘I was issued with a FAL 7.62mm rifle. Other guys were given FAPs – light machine-guns – and others got PAMs [sub-machine guns]. The main emphasis in shooting practice was making every bullet count. I was also shown how to use a bazooka, how to make and lay booby-traps, and how to navigate at night, and we went on helicopter drills, night and day attacks and ambushes. Although we got the basics of soldiering, we still spent most of the time ‘dancing’. B Company was known as the ‘dancing company’ by everyone else in the regiment.

‘At six o’clock every morning we would parade in front of the national flag, salute it, do close order saluting of each other, get danced everywhere, dig ‘foxholes’ or field latrines just to fill in the time. We were never given any proper tests and even on the shooting ranges we had different weapons each time so we never had a weapon we could zero properly and call it a personal weapon. It seemed a continuous punishment of running, crawling, digging and guard duty – and dancing.

‘Even after our forty-five days’ initial training in San Miguel del Monte the dancing continued. We were never left alone. From dawn to dusk it was dance, dance, dance. We even had to dance to the toilets. Then they decided to make B Company a special commando within the regiment. We were the ‘dancing commando’.

‘On 9 March 1982 I was discharged. My conscription was over and I was going to take up the job with the police. I was going to lead a normal life. I was going to be a normal civvy. I screamed: ‘I’ll never come back here again. Yeah!’

‘I was just relaxing back into the civilian way of life when, on 30 March 1982, there was a demonstration in the Plaza de Mayo, right by Government House in Buenos Aires. A guy called Dalmiro Flores was killed, shot by plain-clothes police. I’ll never forget it, because three days later the Malvinas were captured. I was happy we had recovered what I believed was rightfully ours, but I couldn’t help thinking that Galtieri had ordered the taking of the islands to save his position in power because the population was rising against him after the shooting.

‘Rumours soon began to circulate that Class of 62 – my conscript intake – would be recalled. I was in bed at 6 a.m. when the local policeman came round with my call-up papers for war. My mother said: ‘No, don’t go. I’ll hide you in a neighbour’s cellar.’

‘I told her: “I would much rather die defending the nation than be shot on our doorstep as a coward. I want to go.”

‘At 11 o’clock my father and brother took me to La Plaza to our regiment. Outside it was a madhouse, with guys screaming ‘Los vamos a reventar!’ [‘We’re going to thrash them’] and ‘Viva Argentina, viva Argentina!’ Those of us recalled gathered on one side outside the camp. I remember seeing ‘El Ruso’, the Russian, and ‘El Abuelo’ [the grandfather], so called because he was thirty years old. He was studying law and had asthma, but he still ended up in the Malvinas.

‘I remember thinking: These are fools. They’re not thinking what can happen.

‘Then the gates opened and we were greeted with the usual bollocking and shouting. We had to put our names down for a State life insurance. A guy called Massad dealt with that. Ironically he was to get killed over there.

‘That night, after they had assigned us to our company lines, we were all just fucking about, playing around, throwing bread at each other. Nobody was taking it seriously. That’s how it went for a few days.

‘Then, Class of 63 – the conscript intake after our year – returned to the regiment from their basic training. They just grabbed their weapons off them and gave them to us. You should have seen them, all dirty and rusty. They had been doing the rounds of the training units for the last four or five years. We had to strip them down and clean them thoroughly. Some of the new conscripts – remember they had just forty-five days’ training under their belts – were then drafted in with us to fill in some of the gaps in the regiment. Some of them were given new weapons, but I can also remember some really old Mauser rifles, dating back to 1909, being carried by some of the men for sniping. They were really out of date for modern warfare.

‘Next we got our green fatigues. That was on 13 April. Then they gave us all a pair of trainers. Trainers! I suppose they thought we could do a lot of gymnastics in the Malvinas!

‘Different parties of soldiers were leaving the camp at different times. Nobody had told us anything, but we just guessed we were heading for the Malvinas. As we stepped on to the buses to leave, the officers told us our relatives were at the gates and we were to shout ‘Viva Argentina’ as we left so that they could see we were happy to go.

‘We were taken to El Palomar and waited and waited to board a Boeing 707 for a flight to Rio Gallegos in the south. For many of us it was our first time in the air. We thought it would be like it is in the commercials and joked about the service we would get from the flight attendants. There were no flight attendants. There weren’t even any seats for us. Only the officers and NCOs were given seats. The rest of us had to sit on our kit on the floor. We were all there crammed in together. Then the plane took off. I can still see it now - bodies, kit, weapons, everything flying all over the place. It was just like being on a crowded bus when the driver suddenly hits the brakes.

‘At Rio Gallegos there was another long delay – twenty-four hours this time. Apparently the delay was because a plane had gone off the short runway in the Malvinas. So we actually set off for the Malvinas on 15 April.

Kevin Connery was a soldier’s son. His father, Frank, spent twenty-five years in the Royal Engineers, serving in the sort of places the Army liked to use on the recruiting posters – and some they didn’t – raising his large Catholic family of three boys and five girls with his wife Winifred. Kevin was born in Southampton in April 1957 and was soon a seasoned traveller as the family followed Frank on his postings in Turkey, Malaya and Singapore. Kevin’s earliest memories are of Gilman Barracks, Singapore, with its swimming pool which helped the lively five-year-old burn off his near-boundless energy and cool off after playing in the tropical sun. It was also the place where he had his first brush with death.

He contracted malaria and remembers his fear and confusion as his grieving family gathered at his bedside, crying and praying for him. He was not expected to live. But there was a streak of determination running through the sickly mite, a determination to live, a resolve to enjoy more days in the sun at the pool in Gilman Barracks.

Kevin fought the disease – ‘I suppose God had destined me for better things’ – and recovered. It was a long haul, but he made it. Just as he did, his whole life was turned upside down again by the sudden death of his beloved mother. Some of his sisters were by this time in their teens and like every big family they drew together to give each other strength.

Young Kevin continued his schooling in Singapore and began to develop a passion for rugby, one of the great loves of his father’s life too. But nothing is for ever in the Army. Frank’s time was nearly up and he was posted to Marchwood in Hampshire to finish his service. He quickly settled down to life in England again. There was to be no more upheaval, no more moving every few years, and Frank quickly found himself a job. Kevin’s four elder sisters and eldest brother had married and left home and Frank looked after young Kevin, Sean and Kathleen.

Kevin became the ‘potman’ at the local British Legion, collecting the empty glasses and returning them to the bar, earning pocket money and embarking on a new journey, this time of knowledge. He was fascinated by the yarns the old soldiers told as they sank their pints. He was absolutely enthralled by their tales.

At the age of eleven Kevin went to the local secondary school – ‘its name was Hardley and we nicknamed it “Hardley educational”’ – where he spent five unhappy years, being bullied and playing truant.

‘I was skinny, puny and thoroughly bullied. I had sandpaper rubbed over my face and my hands burned on the Bunsen burners. I was kicked and pushed and punched and in the end was frightened of my own shadow.’

He allowed the bullying and the truancy to overshadow his natural intelligence and ability, he now realizes. But despite it all he left school at the age of sixteen with five O levels and two CSEs. He was going to do what he had always wanted to do: join the Army. He had first applied when he was fourteen and had been told he would be welcome in the Royal Engineers, his father’s old regiment. Kevin wasn’t sure, and although he knew all the old soldiers’ stories, he had still not decided what type of soldiering he preferred. But he made his mind up after attending a two-day course at the Youth Selection Centre at Brookwood, near Camberley, Surrey.

‘I saw a poster of a Paratrooper landing ready for action. I knew right away that was going to be me. My brother Sean had already joined 1 Para and he had broken his back. My family was against me joining, but I had made my mind up. I was adamant, 100 per cent adamant. Sean being a Para had nothing to do with my choice.’

Kevin went to the depot as a ‘crow’, a boy soldier. Like everyone else he faced P Company, the rigorous, week-long training for Parachute Regiment selection which sees more men quit than pass. Most of those who drop out do so because they just cannot hack it or decide it is not for them or that they want to try some other type of soldiering with a non-airborne regiment. They become what Paras call ‘craphats’, or ‘hats’ for short. There was no danger of Kevin being consigned – or consigning himself – to the ranks of the hats. Today he remembers the training ‘as a long but worthwhile torture’.

It was also a journey of discovery for him, a long, hard, painful road which saw a wretched little fellow become a self-confident, professional military man.

‘When I arrived I was a kid with no aggression whatsoever – only a puny, picked-on kid. The only violence I had ever used was on the rugby field in tackles, not fighting. The very day I joined, my squad was marched into the gym for a spot of “milling” – a crude form of boxing – under the platoon sergeant, Frank Pye. God, was he a hard bastard!

‘I sat on the bench awaiting my turn to go into the centre. I was shitting myself. The whole thing was scaring the shit out of me. I was shaking with fear knowing I was certain to be beaten up. I knew I was going to get beaten up because I always got beaten up. Nothing has ever frightened me so much. I went into the ring to fight a guy called Nick Newbold, who was the same build as me, and he proceeded as I knew he would – to punch almighty fuck out of me. Then Frank Pye stepped in. He dragged me to the corner of the gym.

‘To the day I die I shall always remember his eyes. He looked into mine, deep into mine, deep inside me. He read my life story there and then on the spot. He had a big face, a big man’s face, and he said: “Go in there and fight all the people who ever bullied you and all the people who ever put pressure on you. Go in there and just fight, just let it go, son.”

‘I went back into that ring and, do you know, it took three adults to pull me off him. I fought with such aggression - it just seemed to seep out of every pore in my body. Frankie pulled me to one side again and said, simply: “You’ll do.”’

That moment of controlled aggression changed young Kevin Connery. He was determined he would pass the course. Frank Pye, a legendary Parachute Regiment NCO, had turned a boy into a man.

Kevin joined the ranks of 3 Para – with the distinctive green DZ flash on the arm of his parachute smock – in 1978 in Germany. By this time he was completely dedicated to the battalion and the regiment, to his comrades, and to the traditions of professionalism and bravery he was required to respect and uphold. Kevin Connery, just like the rest of us, was a Paratrooper from the soles of his feet to the top of his head. All he needed was the chance to prove himself.

As Britain seethed over the invasion of the Falklands the men of 3 Para were leaving their base in Tidworth, Hampshire, for Easter leave. Kevin had already beaten them to it. He was on honeymoon with his bride in Switzerland. As British Rail staff hurriedly scribbled notices to post at all mainline stations saying ‘All 3 Para personnel return to barracks immediately’, Kevin was blissfully unaware of all the drama. He was more concerned with doing what honeymooners do and talking to his wife about their future life together to be concerned about what was happening in the world outside.

As officers and NCOs set about the task of getting the battalion ready for war, groups of excited soldiers dropped everything and poured back to camp. Other teams were tracking down the soldiers who had missed the recall. Some, they knew, would bitch and moan, but there wasn’t a man among them who would want to miss out on the chance of a good scrap. Not even Kevin. When he was found he immediately began his preparations to return to his unit, a decision which shocked his bride, but no one else who knew him. Newly married man or not, it was: ‘Sorry, darling, we’ve got to bin the rest of the honeymoon.’ To be fair to Kevin he wasn’t exactly over the moon about the recall as he had the same first thoughts as many of his mates: that this was just the ‘brass’ saying ‘hurry up and wait’ yet again. He still half believed this to be the case as he kissed his wife goodbye and, heavily loaded down with kit, negotiated the steep gangway of the giant P&O cruise liner SS Canberra.

It was five years since that day when Kevin had first seen the poster of the Paratrooper. Now, as he stood on the deck, he was one. Lean, fit, and with his blond hair cropped and barely visible beneath his red beret, he was ready for anything. He had served in Germany and Canada, but his only operational soldiering had been in Northern Ireland. This was what he had joined for – if it happened. For a little voice deep down inside was still telling him that this was just like the ‘phoney war’ of 1939. Everyone was walking round armed to the teeth and saying: ‘We’ll get there, then nothing will happen.’

Christ, he thought, why doesn’t some bastard just make his mind up and either let us get on with it or tell us to piss off back home. As the Canberra steamed away from Ascension Island, that dust-covered volcanic furnace right in the middle of the Atlantic, ‘some bastard’ had made his mind up. We were going to war. Kevin watched as the great white ship, hemmed in on all sides by other civilian merchantmen and a protective cordon of ‘grey funnel liners’, the warships of the Royal Navy, confidently negotiated the ever-heavier South Atlantic swell. Every day it became colder and the days shorter. A Royal Navy frigate gave a demonstration of its fire-power. Navy and RAF Harriers streaked past, displaying the hardware fastened under their wings. It was all meant to boost morale.

Hercules transporters – from which Kevin had jumped many times and which had been nicknamed ‘Fat Alberts’ by the RAF – lumbered overhead, parachuting mail and more supplies to the fleet. This was when it dawned on him that something big was on and he was definitely going to be a part of it.

It caused him to ponder what lay ahead, and a great swirl of emotions engulfed him. Misgivings and nagging doubts began to eat away at his confidence and excitement. He wasn’t the only man aboard the ship to suffer those thoughts. Most kept them to themselves. They were professional soldiers, for Christ’s sake.

He prayed to himself: ‘What happens if I’m not the Paratrooper the training has programmed me to be? Jesus, what if I become a coward? Oh, God, I don’t want to be a coward in front of my mates.’ As the ship sailed ever southwards, Kevin, like many of the Paras, could no longer accept the luxury of his surroundings.

The training, the programming, the traditions of how Paratroopers prepare for battle, were automatically taking over. They no longer needed the cinema – except for lectures – the well-appointed bars or the comfortable restaurant. They had served their purpose, but they were not needed for men preparing to go into battle. Paratroopers didn’t need this sort of thing any more. It was ‘hat’ kit. They didn’t need to go to war by bloody boat, either. That was for the Marines. He had always believed that if a war had happened in his time he would have parachuted into action, just like the soldier in the recruiting poster, to establish a bridgehead and hold it until the hats caught up and came to hold the line while the Paras fought through yet again to establish another forward area, while the enemy reeled from the onslaught as the ‘Red Devils’, as Hitler had named the Paras, did what they were conceived to do. It seemed undignified, somehow, to be going to war in a landing-craft which looked like a fucking floating rubbish skip.

Like most Paratroopers, Kevin didn’t like Marines. As far as he was concerned, they were just another collection of bloody hats and the sooner he was away from them and fighting the Argies the better. But it was a manoeuvre constantly practised by the Marines which, he maintains to this day, was the scariest thing he had ever had to do since that fateful day when he stepped into that boxing ring back in Aldershot.

The exercise is called cross-decking: stepping from a ship into a landing craft to get to another ship. And the Navy, in their wisdom, decided to carry out this manoeuvre in the middle of the night, in the middle of the Atlantic. Laden like a pack mule, Kevin joined the long line of Paras waiting to step from the wallowing ship into the dementedly bobbing landing-craft pitching under his feet for the short journey into the dock of the overcrowded assault ship HMS Intrepid. He still shivers as he recalls that step from the door of the Canberra, over the glassy black bottomless ocean below to the slippery steel bulwark of the diesel-belching landing-craft as ‘just about the limit of testing one’s nerves’. Once you’ve forced a Para to do that someone will have to pay. So there’d better be a war and it won’t be hard to guess who is going to be the winner! You don’t force Paras to behave like hats and expect to get away with it.